Unbroken Ties

Amanda Lickers introduces Everlasting

Looking across the city, at a territory partitioned into reserves and private lands, dotted with corporate fortresses, monuments, and place names that celebrate colonial conquests, I return the frame of my reflections to the Everlasting Tree Belt. A significant wampum belt for the Haudenosaunee, the Everlasting Tree Belt signifies the burying of the hatchet under the Great White Pine—the Tree of Peace—during the formation of the Confederacy (the union of the original Five Nations—Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, with the Tuscarora joining in the early 1720s due to colonial incursion on their homelands, to form the Six Nations). The belt evokes a commitment to shared values of peace and unity through Kaianere’kó:wa (the Great Law of Peace), which is the original legal framework of this territory. It is the political and governance systems of wampum diplomacy that have set the foundation for democracy and self-determination here on Turtle Island.

In the making of the film Everlasting, I was inspired by the dichotomy of the city and the bush and wanted to amplify this tension to show that our practices are present wherever we are. Being part of the Buckskin Babes collective dedicated to moose hide tanning in an urban context, our focus is to bring the bush to the city. On our territory, we can’t just have a fire, we can’t just go out hunting—there’s a lot of infrastructure that is required to change this, not just material, but legal, as well as social. For me, the concept of placekeeping, as it has evolved through the thinking of Indigenous architects like Wanda Dalla Costa or Matthew Hickey, challenges the notion of placemaking in architecture and urban design. Where placemaking suggests that we need to develop and create a space, placekeeping instead reinforces an understanding of interconnectivity and implies that the territory already is a place and that ecological and sociocultural systems as they pertain to land must be accounted for in design. Our practices, such as hide tanning, already have a symbiotic relationship with that place. Placekeeping supports Indigenous epistemologies of interconnectivity, interdependence, and deep time in our continued presence through cultural transmission. If we want to really have meaningful sustainability in architecture and the built environment, then we must have Indigenous sovereignty.

Everlasting follows the placekeeping power of unbroken ties to territory through local seed saving and hide tanning initiatives. These ways of being and doing refuse settler partitions of land and city and challenge settler geographies of terra nullius. I’m interested to see the conversations that we can develop through creating visibility of our cultural practices in the urban environment, and the ongoing engagement that we can continue to generate through this film and exhibition over the next year.

The visual storytelling in the film was critical. I was very interested in juxtaposing and layering some of the archival photography from the McCord Stewart Museum, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, and CCA collections with contemporary footage—placing imagery of current-day deer leg cleaning or processing overtop historical images of the fur trade and settler colonial flags at the municipal, provincial, and national levels. This has a multi-faceted meaning as historically, up until the 1951 Indian Act amendments, it was illegal for us, as First Nations’, to practice our culture anywhere—and particularly within city boundaries. I thought it was important to show the layers I move through as an Indigenous woman in the urban setting by contrasting selected iconography in order to tell some of those more nuanced stories visually, giving some background to the contemporary context that Marnie Jacobs, Brooke Rice, and Autumn Godwin share with us on screen.

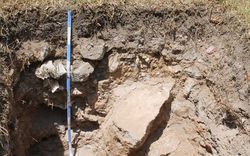

There were some unexpected moments during the filming process. One day, we were filming at the Droulers-Tsiionhiakwatha site, which is an archaeology site and interpretation centre in Saint-Anicet, Québec. It is basically a Haudenosaunee village with replica longhouses. The day we went it was pouring rain, but we captured some beautiful and unexpected moments. We were so lucky to get lightning strike—that was amazing and invigorating to shoot. At one point, it was really pouring down, heavy, cold droplets, and we weren’t fully prepared to shoot for hours in a full-on downpour, so we had to pack up early. The rain came down so hard that they had to close the site early.

On another day, when we were filming the deer cleaning, I came across this deer needle bone. As I was doing research for the Droulers’ site shoot, I came across some forensic archaeology that noted these use-wear marks on a deer needle bone that they had found around this original Haudenosaunee village, that had shown it was originally used as a tattooing device.1 It was really inspiring to me that this example of material culture, which had helped cultural transmission and survived all this time, could bring the Droulers’ site into a space of being preserved and protected. Not only that, but I had harvested this exact tool from the deer leg processing that I had filmed on site at the CCA for this project; this tool was an archaeological signpost that made its way into my hands in 2025. The connection of deep time made itself known in the making of this film.

-

Christian Gates St-Pierre, “Needles and bodies: A microwear analysis of experimental bone tattooing instruments,” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 20 (2017): 881–887, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.10.027. ↩

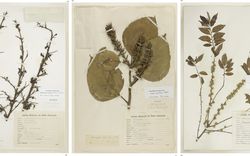

Throughout the film there is close-up footage of plants, which has multiple intentions. On the one hand, I thought that showing these plants would be a reference for other Indigenous folks who will recognise them and know their applications. Through this intimate composition I put an emphasis on plants at ankle height, to simulate walking in the woods. I prioritize these cropped, zoomed in frames to literally and figuratively put the viewer through my lens, to see things in my vantage point through a worldview that values the mindfulness that come with bush practices. As I rewatch the film, I take pride in the relationship between shots either through composition or content as a storytelling device. In another light, the significance of these forest shots contrast with the “Doctrine of Discovery” and terra nullius, as Indigenous peoples were classified as “sub-human” alongside “flora and fauna” according to a 1493 papal bull. This declaration provided the political and legal justification for expansion through colonization—it becomes a lot easier to implement slavery and genocide if you see Indigenous Peoples’ as non-human or sub-human. We are—through both a colonial and decolonial lens—the same height as the fauna around us. A very Western way of thinking is to view the natural world as separate, where the land is an object, dead, something that can be commodified as a resource. Further to that, Western worldviews position humanity at the top of the imagined hierarchy. Whereas within onkwehonwe’neha (“our ways” within Haudenosaunee worldviews, Indigenous methodologies) humanity is part of the circle, beholden to the cycles of interdependence, and we understand the land as a living relative, where we are borrowing something from our future generations. So, this idea of interconnectivity, caring about migration patterns, caring about the turn of seasons, caring about ecological biodiversity, sociocultural transmission and reciprocity with territory is also our collective ability to have a future, to survive. We’re seeing that from the framing of deep time—colonial capitalism hasn’t done so well for the planet in a very short amount of time. We can also see that Indigenous knowledge systems, Indigenous sciences and technologies, are continuously being referenced by emerging Western sciences as the signposts forward to address climate catastrophe. As Brooke Rice says in the film, our practices are having an ecological impact that we don’t even know yet.

At the very end of the film, you see an image of Onondaga Chief Isaac Hill who was photographed in Kanehsatà:ke as he was visiting on business from Six Nations of the Grand River (Ontario) in 1870, where he is holding a wampum belt. When we document our land-based practices, we focus on the hands to focus on the practice. I thought it was very interesting to layer this image over the present-day footage of Brooke’s hands cradling the heirloom seeds, emphasizing the connection between governance and sustenance, really implementing visual culture to highlight the continuum of our practices and our continued presence. As Autumn Godwin states so eloquently in the film, “land back” is not just material, but it is ontological and multi-faceted through language, culture, and ways of being. Interlacing past, present, and future, this imagery and the project itself go on to affirm Indigenous peoples’ connection to the land beyond the past—as everlasting.

Everlasting is presented in the CCA’s Shaughnessy House until August 2026.