Noise Versus Noise

Geoff Manaugh in conversation with Sabine von Fischer

I caught up with Sabine von Fischer for a brief Q&A; about her work after she delivered a lunchtime lecture on Monday, 28 June 2010.

The ever broader range of equipment installed in buildings has turned what were once places of private retreat within closed walls into hyperactive spaces with constant background noise. Measures to regulate sound transmission, insulation, controlled acoustic irradiation and the constant hum of air-conditioning have fundamentally changed the auditory environment, as well as the relationship between interior and exterior spaces.

In an investigation of sound spaces and atmospheres in the nexus of aesthetic, cultural and technological change, 20th century architectural history is rendered audible and regarded from a new angle, in the light of a cultural history of the sound of architecture.

—Sabine von Fischer

- GM

- In the most general terms, what is the topic of your dissertation?

- SVF

- The Ph.D. will be a history of 20th century architecture, with sound being the filter through which I want to look at different spatial configurations, building technologies, and the mutual effect of technologies and architecture on each other. The period that I am looking at is 1930-1970; this was a period when drastic changes in acoustic technology happened that continue to impact our environment today.

- GM

- Why do you begin in 1930?

- SVF

- 1930 was the first publication of the tapping machine—that’s my case study for building acoustics. The 1970 date is maybe a little more vague—it’s a nice even number! But if I find other events, I might change it to 1971. [laughs]

- GM

- What was the tapping machine?

- SVF

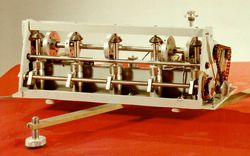

- The tapping machine, as it was first published in 1930 and as it was standardized in the 1960s, has five steel rods that hammer against the floor. The speed has changed a bit over time—and its speed is now standardized—but it just tramples on the floor. It’s a very basic machine.

The principle of the machine can be found in older apparatuses, such as those used in grinding food items, but this particular application was to simulate the sound of footsteps, furniture, and machines on the floors of multistorey buildings. In this form—with five hammers, which are electrically operated—it was first published in 1930, in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America.

- SVF

- Everyone who has been working on building acoustics claims that, since 1923 or 1926, they’ve been doing similar tests on structure-borne sound, but almost all of those earlier tests were done with women in high-heeled shoes. High- heeled shoes make a very distinct sound. For impact-sound measurements, these women—and I have never seen a photo with a man or a documentation of a test done with a man—would wear high-heeled shoes, making a very standard noise.

Obviously, there have been comparative tests with men wearing different-soled shoes, evaluating the different ways of walking—or people who are very heavy, who produce different frequencies in the floor—but the National Bureau of Standards, in the period between the wars, had ladies in high-heeled shoes walking around inside buildings. - GM

- Did the tapping machine put those women out of work, or was it used in parallel?

- SVF

- I think they were replaced by the machine—but, then, people came back in over the last decades, mostly for measuring sound inside the same spaces. Because, once there is sound insulation in the floor, there’s a new problem: sound gets thrown back into the room. It’s not transmitted into the lower floors; it wanders around the same room. Especially with laminated flooring, there can be a strange sound when people are walking inside their own spaces. To test that, it’s done with people; the tapping machine wouldn’t simulate it well enough.

- GM

- I’m reminded of Nightingale floors in Japan: deliberately squeaky floors installed as a security measure against ninjas and assassins. The idea was to make the floor as acoustically noticeable as possible, rather than to mitigate its sonic properties.

- SVF

- In Indian culture, as well, there’s a related example, where often the lady of the house would have a ring on her toes so that the other people in the house would know when she’s approaching. Different cultures have different traditions of using sound to mark someone’s presence in a building.

- GM

- Going back to your Ph.D. research, can you explain your idea of the “clairaudient building”?

- SVF

- The “clairaudient building” is a metaphor, because normally you would say that a person is clairaudient.

- GM

- It’s like clairvoyant—clairaudient is a kind of supernatural “all-hearing”?

- SVF

- Yes, I am using “clairaudience” to refer to early and post-war modern building systems, which transmitted sounds much more than any traditional way of building, creating problems that were unheard of before. Then, the word clairaudience, to me, also spans all of the technological machines and apparatuses that are used to broadcast sound inside architecture—speakers, microphones, intercoms, all the way up to surveillance systems and equipment. So buildings became clairaudient through technology.

- GM

- In that sense, a clairaudient building would be a space of total acoustic transparency?

- SVF

- Yes, and I also think acoustic transparency is a quality of ambience—what became known as the “atmosphere” of a space. Very often, for example, you can observe that once rooms are silenced, other sounds are introduced artificially because, in the end, total silence doesn’t feel comfortable.

- GM

- That’s interesting—as someone who has very bad tinnitus, I need to have some kind of noise playing at night or I can’t go to sleep. So my wife—I hope!—has gotten used to the fact that we have to have fans on, even in the middle of winter, and sometimes more than one. But what’s interesting about tinnitus is that a silent room is not necessarily socially uncomfortable—in the sense that you need to think of something to say to the people around you—but, speaking only for myself, acoustically uncomfortable. I can actually feel dizzy sometimes when it’s totally silent due to all the ringing in my ears.

- SVF

- I would say that the term tinnitus can also be applied to buildings and to cities in general. I think sounds in cities and buildings have moved from being distinct signals, or individual sounds, to a constant background. There is often not one loud noise, but a mélange or a multiplicity of dampened—yet still audible—machines.

This will sound too harsh, but it’s as if all contemporary buildings have tinnitus. That’s an image I want to work on—a pathological metaphor for the state of sound in architecture.

- GM

- In your presentation you showed a photo of a man sitting at a desk, smoking a cigarette, listening to the sound of his air conditioner.

- SVF

- Well, this is from 1958, a man being bothered by his air conditioner! The ad suggests that he should buy a new model because it’s more silent.

I’m fascinated by that image, because it visualizes the constant quest for new technologies that we need simply to make up for the downsides of the previous new technology. For instance, once rooms were air-conditioned, there was the sound of the air conditioner that we had to make up for; and, I assume, this new air conditioner in 1958 was not as silent as we are used to now—and, even today, air conditioners are not silent at all.

- GM

- The example of air conditioner noise points to an interesting line between the equipment of everyday domesticity—refrigerators, ceiling fans, air conditioning units, even tea kettles—and what could be called proto-musical instruments. They are things that you can tune to make the world quieter or more melodious.

- SVF

- That’s definitely something I am interested in, although I think that this specific kind of sound design is something that only came after 1970.

It’s all a question of attitudes or personal taste, so tuning everyday objects can be a quite difficult enterprise. There will never be a consensus on what a good sound is. That’s why the noise regulations in cities are so rigid, because there are so many different reactions and compromises in order to avoid being a nuisance to someone.

Different sounds can also mean different things. Lawnmowers are always loud because, if a lawnmower was very quiet, maybe people wouldn’t buy it for fear that a quiet lawnmower isn’t strong enough. And men’s shavers are much louder than ladies’ shavers, even though they do the same thing. There are a bunch of products around us that are already heavily sound-designed. - GM

- Even police sirens are being redesigned. In New York City, for instance, a new siren called The Rumbler was introduced last autumn that uses subwoofers and heavy bass to cut through urban noise (and through the music you might be listening to in your car). It’s like sonic warfare—noise v. noise.

- SVF

- There was also a project by Max Neuhaus, from the 1970s, where he designed new sirens for emergency vehicles in New York City (PDF). His contention was that drivers and pedestrians in the city could not locate where the existing siren sounds were coming from. You would hear a siren somewhere but not know where it was. So he designed a better sound that, he claimed, you could hear which direction it was coming from. He invested a lot in the project, and I think he was quite frustrated when it never made it into the actual system.

- GM

- Finally, when it comes to specific resources here at the CCA, are you here more for the research & writing time, or is there a specific object or text in the archives that you came to see?

- SVF

- It’s primarily to have the freedom to really think and focus, but there are things that I want to look at. The archive here is very strong in post-war visionary projects, and I’m looking at their ideas of utopia and the role of technology in buildings and interiors. I’m interested in the audio component of the social utopias of the 1960s—to see what role sound played in projects of this period. One famous example would be François Dallegret’s illustrations for Reyner Banham’s text “A Home is not a House” from 1965.

Artist and sonic historian Sabine von Fischer, was based in our study centre in 2010. She spent her time here as a Visiting Scholar researching the relationship between architecture and sound for a Ph.D.

Geoff Manaugh was also here in 2010 Visiting Scholar and as part of the To CCA, From… program.