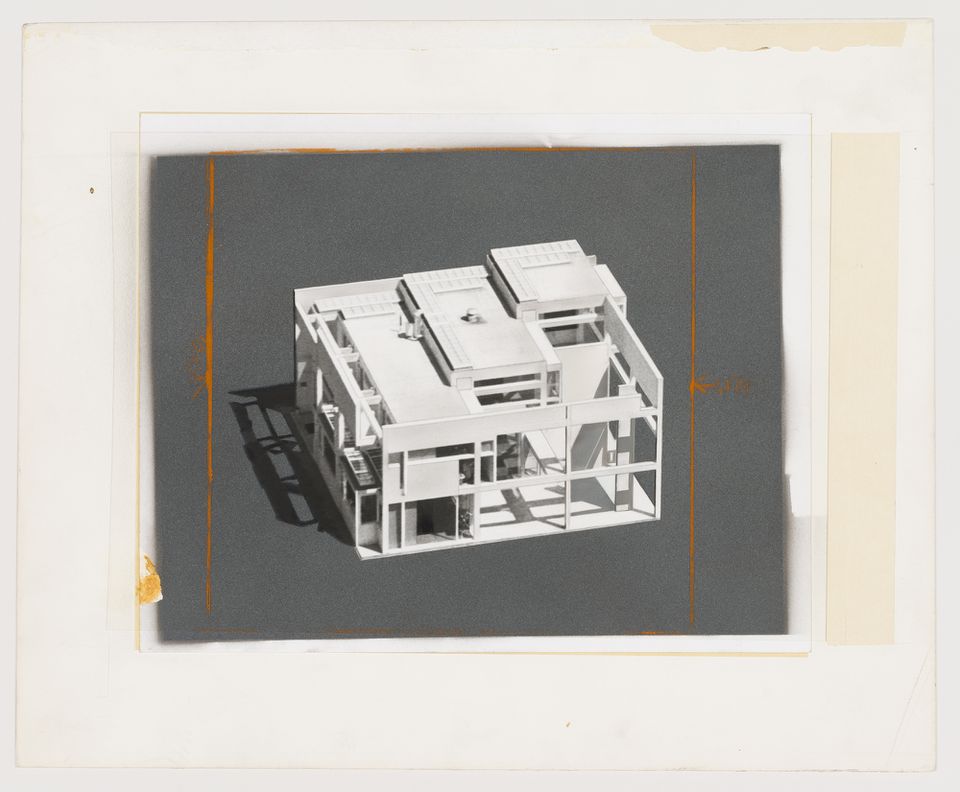

Model for Falk House (House II)

Sarah Hearne on a mislabelled photograph

Sometime between the spring of 1972 and the fall of 1973, Randall Korman, then an assistant in Peter Eisenman’s office, rented a Piper PA-28 “Cherokee” from the White Plains airport in Upstate New York and flew it to Hardwick, Vermont. There, using the piloting skills he had acquired during his recent military service and a Konica SLR camera with a telephoto lens, he took a photograph of Eisenman’s recently completed House II from above.1 The idea for this expedition was Eisenman’s; the photo was to act as a proof of sorts, a test of the building against its concept. The resulting roll of film captured the house from a viewpoint that once claimed the objectivity of surveillance, but one which was quickly becoming a representational trope in the postmodern period. Each snapshot involved moving between the controls of the plane and those of the camera. Korman would bank the plane’s wings and remove his hands from the gears to snap photographs, before retaking the controls and circling the plane back again to repeat the shot. The plane’s droning engine was audible from the ground, just loud enough to draw the client’s son to the window, where he was captured in the frames—a small but visible figure pressed up against the glass pane.

In an interview some nine years later, Peter Eisenman stated, “House II was built to look like a model (often when the photograph of House II is printed in a magazine, it is mistitled as a “model photograph”).”2 This statement is worth revisiting in light of a mechanical document housed at the Canadian Centre for Architecture and catalogued as a “view of model,” although, like the photograph described by Eisenman in the interview, it contains an aerial snapshot of the constructed House II. The consistent mislabeling of the mechanical sheds some light on the unexpected marshalling of airplanes, cameras, airbrushes, and anonymous collaborators, as well as on the media conventions that were required in order for Eisenman to fabricate a convincing image and have it circulate with an invented label. It is, however, these very acts and their deliberate repression that position this photograph within the broader narratives of postmodernism’s image culture, amplifying the effects of reproduction, and critically manipulating systems of communication—including the media formats across which images were duplicated and circulated.

-

Description of the event is based on phone interviews and email exchanges between Randall Korman and the author in 2018. ↩

-

Peter Eisenman, quoted in an interview with David Shapiro and Lindsay Stamm. “A Poetics of the Model: Eisenman’s Doubt,” in Idea as Model, ed. Kenneth Frampton and Silvia Kolbowski (New York City: Rizzoli, 1981), 121. ↩

In this reprographic context, mechanical documents—layers of “copy” pasted up for plating and printing—were primary sites of work and were rarely seen outside of printer’s studios, if at all.1 Like all examples of mechanical documents, “view of model” bares each layer of activity and communication that would be rendered invisible in the published image. In this case, the mechanical reveals the shift in efforts from the geographical to the minutiae of post-production, where a retouching artist applied a combination of material processes that collectively isolated the house from its context, scale, and materiality. The figure of the curious child at the window was erased as was the vitality of weathering from the house’s roof and facades. Layers of bleach, white gouache, and graphite, all common toning treatments, were likely applied to several of the building’s surfaces, amplifying the brilliant white paper effects that made the house appear to be constructed from cardboard. The landscape was dusted with an airbrushing of grey paint, leaving the house to float in isolation, as though on a melamine desktop. In the most obvious act of design, the shadow of the house was drawn onto the new backdrop, its contours mapped onto the surface of the print rather than onto the topography of the erased landscape. The shadow’s outline was drawn freehand with a softened edge, its geometry recalling the contested history of skiagraphy, in which techniques of drawing shadows either by memory and observation or by way of exacting calculations signalled larger divides between facticity and interpretation.2

Ultimately, all of these efforts were to be imperceptible erasures and the act of making these signs of production invisible was necessary to maintain Eisenman’s ideas around conceptual architecture—where buildings were not prioritized but only incidental to process. This was not an architecture of site visits but rather one with effects better demonstrated through reproduced images alone—inked in publications or projected onto walls during lectures. The aerial made its first published appearance in Eisenman’s House of Cards, which was explicitly organized in chapters named for established phases of architectural design, from the sketch to building photography—a structure that facilitated the mislabeling by filing the doctored aerial amongst model photography.3 Perhaps a curious choice of organization for the book, especially given Eisenman’s early interest in designing process, which on the one hand deflated the amount of attention given to the building and on the other hand inflated the amount of material destined for publication, while simultaneously challenging the very same phases of design. Similarly, the efforts around the mechanical document switched the conventions of documentary photography concerned with the “finished” and constructed building, with model photography, which was understood as closer to some originary moment.

These activities occurred at a moment when the value of architectural models and drawings was rising in relation to their use as research documents by architecture historians and also as collectible originals, as galleries and architects attempted to expand their market shares.4 Part of this reappraisal included attention to the nomenclature for drawing types, as cataloguing standards sought to locate the drawing’s position in relation to the broader design process.5 Many argued for the higher value of drawings that were believed to testify to the “first thoughts” of the architect, reinforcing the long tradition of the authority of the sketch based on its immediacy. While it might seem as though these attempts to imbue value to authorship were antithetical to Eisenman’s pursuit of a design process that was “transformational” rather than author-driven, it would seem that the mechanical document attests to both a persistent attachment to the original, achieved, as it is, by other means.

-

Preparation of the mechanical sits in between the creative work of sketch design and layout and the reproduction work of platemaking and printing in the production cycle. For an extended discussion of mechanical documents and their preparation, see Bernard Stone and Arthur Eckstein, Preparing Art for Printing (New York City: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1965). ↩

-

Interest in skiagraphy reappeared in various accounts of drawing and representational history. For instance, see Robin Evans, “Architectural Projections,” in Architecture and Its Image: Four Centuries of Architectural Representation: Works from the Collection of the Canadian Centre for Architecture, eds. Eve Blau and Edward Kaufman (Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture, 1989), 27–28. ↩

-

According to Eisenman’s preface, the development of the book began in Eisenman’s office around the time of Korman’s aerial jaunt, some thirteen years before it was published in 1987. ↩

-

The values attributed to drawings were marked by a lack of knowledge that reflected in the inaccuracies of institutional cataloguing. Efforts like those by figures like Margaret Richardson at the Royal Institute of British Architects reflect an attempt to stabilize the terminology of design phases or what she called “stage of realization,” emphasizing the value of early signature sketches and lamenting the “regrettable” practices of redrawing, tracing, and delineation, which set up a distance between the originary moment in favour of reproducibility for publications. Margaret Richardson, “Architectural Drawings: Problems of Status and Value,” Oxford Art Journal 5, no. 2 (1 January 1983): 13–21. ↩

-

In 1973, Paul Rudolph wrote an introduction to a compendium of architectural drawings, in which he stated: “The age-old process has not changed much. The idea, transmitted to the sketch, often augmented by models, is developed into a rendering, which in turn is translated into working drawings. These evolve into a building, which is a basic part of urban design.” Curiously, four years later, the same book was reprinted with a modified title, which changed from Drawings by American Architects to Presentation Drawings by American Architects. This addition signifies that the simple and timeless clarity of design phases were perhaps not as straightforward as Rudolph proposed. Paul Rudolph, “Foreward,” in Alfred M. Kemper, Drawings by American Architects (New York City: Wiley-Interscience, 1973), i–ii. ↩

This text appears in Architecture Itself and Other Postmodernization Effects.