The Discovery of Absences

Martien de Vletter outlines a process of reparative description

The CCA has been collecting ideas on architecture since 1979 with the goal of building up a productive resource for researchers worldwide. All material that enters the Collection is recorded: books, periodicals, toys, and miniatures are catalogued in a library database; photography, prints, and drawings are recorded in an object management system; and archival holdings are described in finding aids.1 Descriptions are created to identify objects or groups of materials, to manage and track materials, and ultimately to make them accessible for research.

Today, many museums and collecting institutions are evaluating their role and influence in society, specifically in terms of how they might perpetuate systems of injustice and exclusion. Museums are increasingly being questioned about both the provenance of their collections and their description practices—are museums neutral and can descriptions really be considered objective? The modern museum itself was established as part of a colonial cultural system that removed artefacts from their original context and made them available to often only a select group of visitors and researchers. And yet, the museum is also a space within which to reconsider and reexamine cultural entities as well as policies and processes of collecting and describing.

We never considered that, in the context of the CCA, being a custodian of architects’ archives and of photographs, or acquiring books and periodicals, was a colonial act and yet we have undeniably contributed to establishing the canon of whiteness in architecture. In our collecting strategies, certain concepts, peoples, and genders have been privileged over others. In light of this realization, it is now imperative to revisit our strategy of collecting as well as when and how we describe objects. These descriptions are produced when objects enter the collection and they tend to become permanent—they are rarely revised, even when new research on the objects becomes available.2 For areas of knowledge with terms that evolve rapidly (such as in studies related to gender), cataloguing processes cannot constantly adapt as it would simply require too much research. Collection descriptions are never entirely up to date and are therefore themselves historical records. For a long time, we did not question how descriptions could perpetuate injustice and exclusion. This is changing. We are now working to expand descriptions to make otherwise underrepresented yet relevant aspects of an object’s history accessible and, more importantly, discoverable.

Descriptive practices are not as neutral as we long thought they were. In their 2002 introduction for Archival Science, photography specialist Joan Schwartz and archivist Terry Cook write that modernist thinking led to the positive notion of describing as a neutral act and of the archivist as an “impartial [and] honest broker between creator and researcher.” However, as they go on to write, “postmodern archival thinking requires the profession to accept that it cannot escape the subjectivity of performance by claiming the objectivity of systems and standards.”3 The CCA’s cataloguing and description standards now cause issues pertaining to a “hierarchy of sameness,” a phrase coined by Hope A. Olson, a professor of information studies who examines the biases inherent to classification systems.4 Hierarchies, especially in the controlled vocabulary of a library database, privilege the “first term” or a single aspect of an object—this vocabulary is of course informed by structures of cultural and social power. What makes an object or a person primarily defined by one characteristic or context rather than another? This question is especially important, as it is the choice of descriptive terms that define a database search result.

-

Since 1999, materials in the library collection were catalogued in the library database Horizon. The CCA recently migrated these records to a new platform, WMS, while photographs, prints & drawings, and archives are described in TMS. Archival data is currently being migrated to an archival management system called ArchiveSpace. These databases “feed” the online access interface, which is hosted through the CCA website. ↩

-

Description practices for library material are historically more structured and standardized than description practices for museum objects such as photographs, prints, and drawings. Archival description practices are different altogether. Only recently have archival description practices been updated to rectify injustice and exclusion, as seen for example in Archives for Black Lives in Philadelphia (October 2019), a resource compiled by the Anti-Racist Description Working Group. ↩

-

Joan M. Schwartz and Terry Cook, “Archives, Records, and Power: From (Postmodern) Theory to (Archival) Performance,” Archival Science 2 (2002): 176. ↩

-

Heather Lember, Suzanne Lipkin, and Richard Jung Lee, “Radical Cataloging: From words to action,” in “Libraries, Information and the Right to the city: Proceedings of the 2013 LACUNY Institute,” special issue, Urban Library Journal 19, issue 1 (2013): 2, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ulj/vol19/iss1/7/. ↩

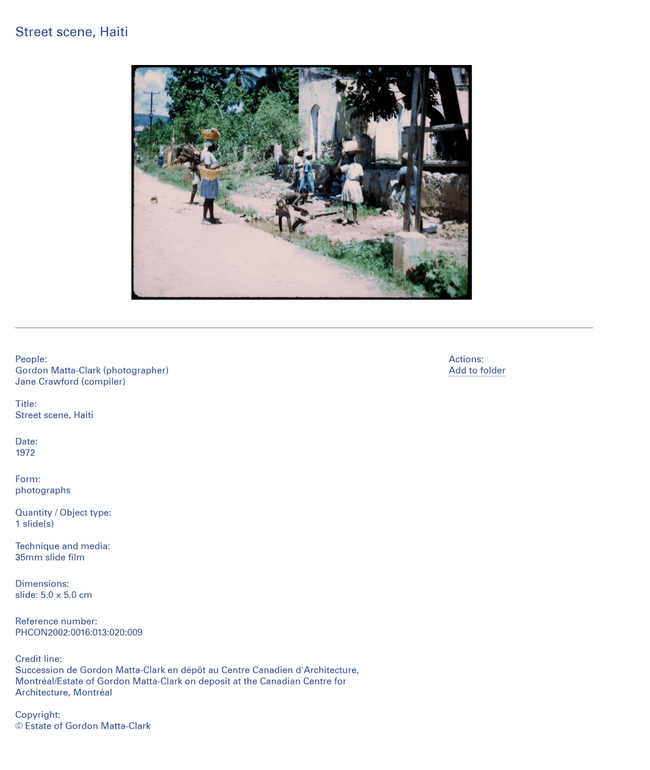

For example, while there is a lot to see and describe in this photograph taken by Gordon Matta-Clark in 1972, our description, indicating only a general location, is minimal and so does not allow for a wide range of possibilities to increase discoverability.

Describing objects as individual records also results in a loss of context, especially in terms of how they can be consulted online. The above photograph is actually part of a collection of hundreds of slides Matta-Clark took during his travels, only a selection of which have been digitized. Despite the endless opportunities to link from one webpage or website to another, viewing a historic photograph as an online reproduction is not the same experience as seeing it in our study room, and certainly not the same experience as seeing a work mediated by a curator, librarian, or archivist, as was the practice until websites and their online catalogues took over. The curator would give the researcher the context, or would be there to discuss it, and so the catalogue descriptions could be minimal (they served to trace works for future discussion). Context is lost in virtual space, as the written record is all you see. In the physical space of a study room, this context may be hidden in reference material—paper acquisition files and research documents available in drawers or index systems—but it is there.

To return to our collecting practices and questions of descriptions, the children of Argentine architect Amancio Williams (1913–1989) recently gifted to the CCA what was called the “Williams Archive.” The CCA was criticized on Instagram by Couplings Tactic (an initiative of Inés Toscano, investigating and mapping couples in architecture, pointing out that often the women go without notification), who called on us to make sure Amancio Williams’ partner in life, Delfina Gálvez Bunge, is considered an equal contributor the body of work.1 Architecture is an inherently collaborative practice, and yet in the descriptions of architecture archives we tend to credit only a single individual and the transmission of knowledge or collaboration is not questioned. But some architects specifically define how their work should be credited. For example, upon the transfer of his archive to the CCA, Álvaro Siza insisted that we credit and recognize the architects he collaborates with—but not all architects make this a requirement.

Why are we concerned with making descriptions inclusive and just? Collection descriptions are key for discovering sources and ideas, increasing access, and therefore advancing knowledge. Descriptions are also contextual, framed by geography and time. Questioning our descriptions can support changes in research practices and in long accepted but perhaps biased concepts. Cataloguing processes and the production of collection descriptions are as much the outcome as the enabler of research and so must always be open to revision. Because object descriptions are not frequently revised and because online descriptions are easier to find than research published in an academic article, those writing new object descriptions must be much more aware of the impact of narratives, assumptions, and patterns. Language matters, even more so in our digital world built according to language-based algorithms.

As the CCA, we continue to learn about the limitations of search engines and interfaces and the databases that they draw from. As a user, one cannot know how, and how deep, a search engine searches a database and therefore if all the possible results are returned. Mapping databases and the migration of data over time has been problematic as a lot of data kept in the CCA collection databases does not appear in the online search and is therefore not discoverable. The limits of the search engine, or the manipulation of our searches, are equally problematic. An issue of language becomes an issue of algorithm.

The CCA’s Critical Cataloguing project, started in September 2020, reviews our current object descriptions and can be used as a model for the CCA’s wider collecting practices moving forward. Critical Cataloguing intends to incorporate inclusive description and metadata strategies to improve discoverability.2 The project began by identifying the most harmful language used in records across the CCA Collection—including words like slave, Indian, albino, and servant—and we have now started to revise constructed titles (meaning titles assigned by a cataloguer, not the original title given by the artist) in records of the photography collection. The words and terminology that we look for are defined by various lists shared among librarians and archivists, such as the Harmful Description Lexicon created by Princeton University.

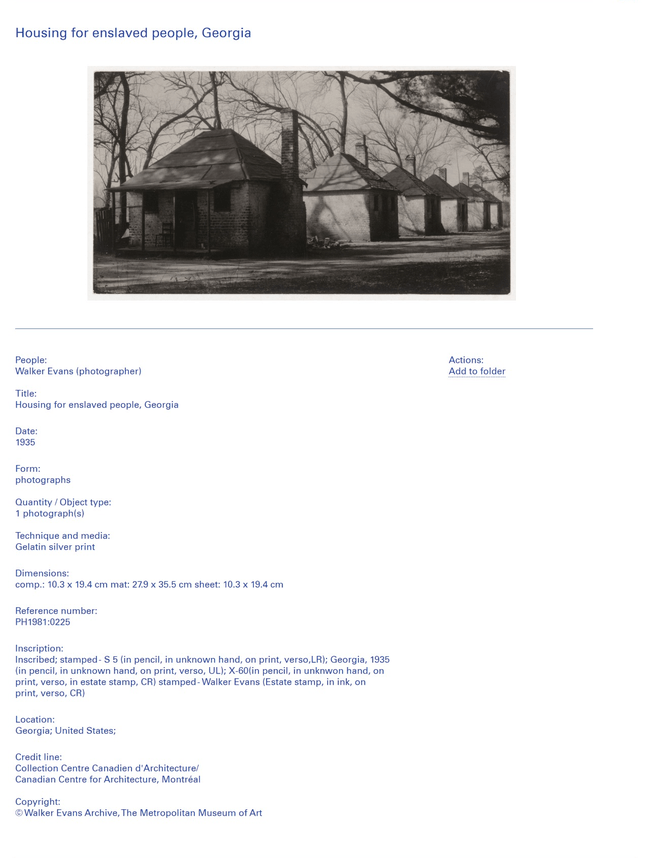

The above photograph by Walker Evans had a constructed title used by many other collections as well. The team started to compare the descriptions in other collections and decided to not only change the word “slave” into “enslaved,” according to best practices, but also to change the word “quarters” into “housing.” We have discovered that certain words are considered harmful in one context but remain benign in others. “Peon,” for example, is considered harmful in a North American context but not necessarily in India.1 This means we have to be careful when applying or changing descriptive rules across collections. Similarly, we want to address language related to Indigenous people, which requires research and outreach to communities and experts in this field.

-

The use of the word “peon” will be elaborated on in a forthcoming article, to be published on the CCA website in early 2022. ↩

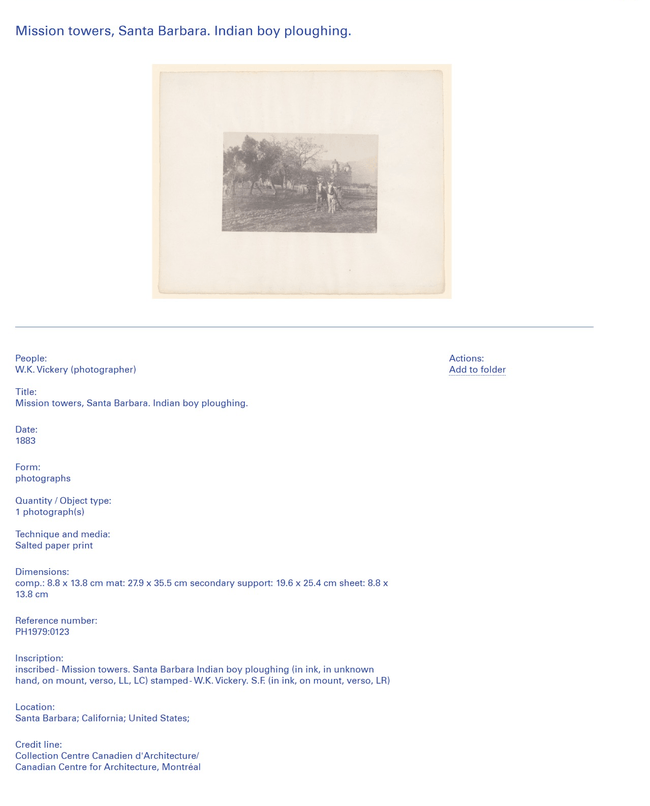

The inscribed title for this 1883 work is “Mission Towers, Santa Barbara. Indian boy ploughing.” But who inscribed and described this work? In order to derive a more inclusive description we need to expand our knowledge of the Indigenous communities in Santa Barbara at that time and decide whether to foreground the activity of ploughing or the architecture.

The next, more complicated, phase of the Critical Cataloguing project has only just started: to identify problematic but regularly used concepts and to identify absences. Not having a description at all or having a description that is missing information, can be as problematic as descriptions that use harmful language. In many cases it is a combination of the two issues that we are addressing. In the coming months, we will share cases that show the limitations of descriptions and language but that also demonstrate the value added if they are revised to be more inclusive in their scope of information. We will share the problems we face in terms of the absence of descriptions or of how language can misguide the reader and researcher. Obviously, there are many records in our catalogue that are incomplete or very minimal, which makes material difficult to find. But there are many ways to enhance descriptions. The goal of Critical Cataloguing (or the process of reparative description) is to specifically address issues of injustice and exclusion.

The work of interpretation is traditionally the domain of the researcher, who incorporates an item into the context of a specific discourse. This is different from the technical practice of cataloguing or describing, which is traditionally the domain of the cataloguer or archivist, who tries to use consistent terminology (metadata) for multiple records in order to enable the discoverability of all items about one subject. Subjects exist with different scopes—there is the subject of housing for enslaved peoples and then narrower subjects on such housing in specific periods and places—and the language informing the metadata has to work consistently at all these levels. However, today the work of interpretation is done alongside the work of cataloguing. The one supports the other, roles merge, and the work of interpretation reveals insensitivities, biases, and logics that must be taken into account when cataloguing.

A series articles published in the coming months will reflect on the value of interpretation in combination with the technical practice of cataloguing. These reflections are helping the CCA create meaningful and inclusive descriptions to increase the discoverability of histories, narratives, and contexts that would otherwise not appear in object records. We welcome you, the reader, to reflect, criticize, and respond to our efforts.

I want to thank and acknowledge the team with whom I started the work of critical cataloguing: Caroline Dagbert, Christine Lefrancq, Hester Keijser, Jennifer Préfontaine, and Mary Gordon. I also want to thank Matthew Kalil, Albert Ferré, and Claire Lubell for their valuable edits.