In the Scale of the Planetary Field

Émélie Desrochers-Turgeon and Eliyahu Keller

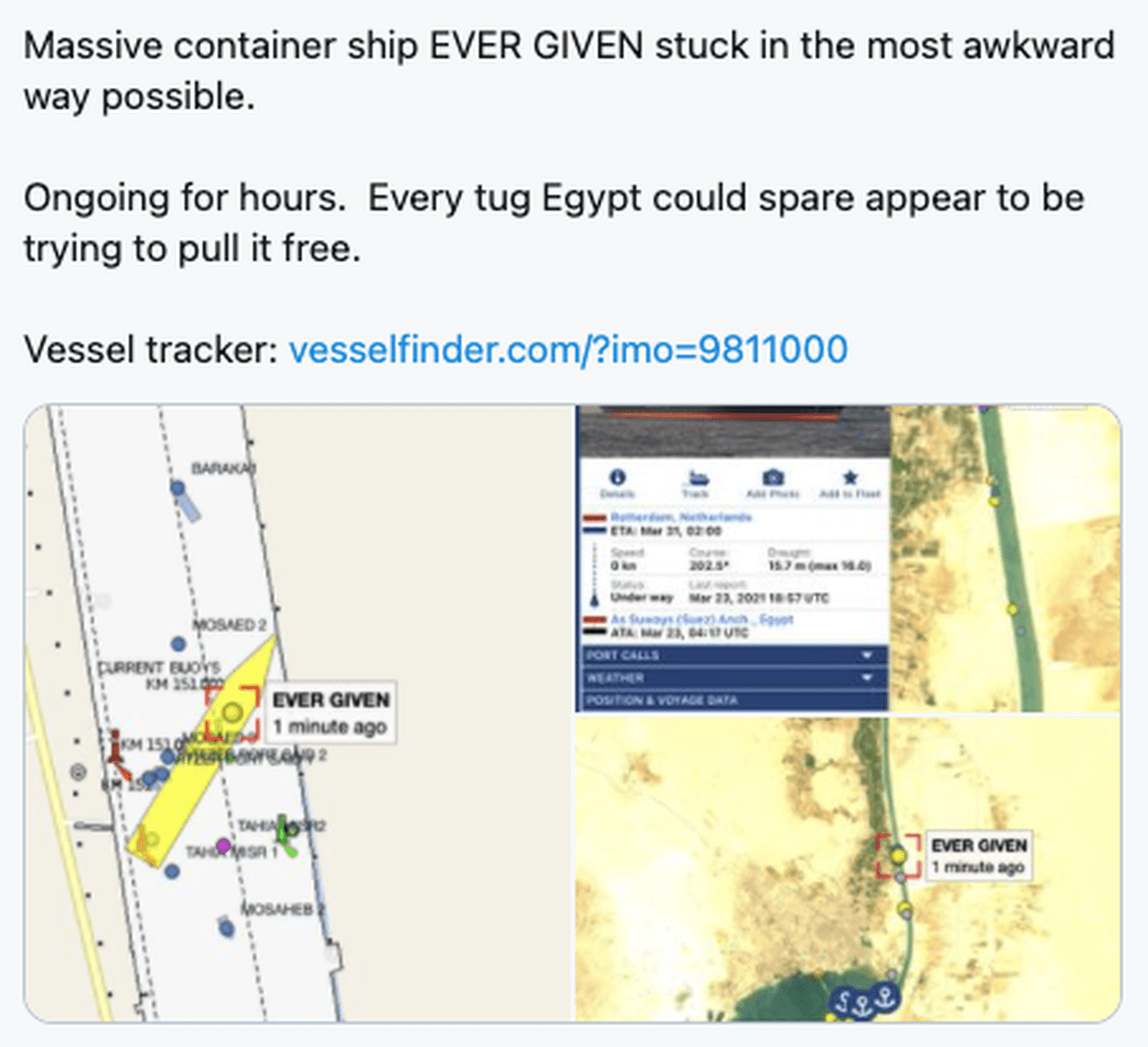

On the morning of 23 March 2021, the Ever Given—an approximately 400-meter-long ship carrying over 18,000 containers with a gross weight of 220,000 tons—was derailed by strong wind gusts (and perhaps by human error), blocking the 200-meter-wide Suez Canal and delaying global trade and logistics. The obstruction lasted a mere six days, enough time to impede approximately 300 ships carrying an estimated 17 million tons of goods. The immediate economic impact was correspondingly astronomical: financial losses were appraised at around USD 400 million per hour, equating to an unfathomable loss of USD 10 billion per day.1 The localized impact, though it paled in comparison, was still significant: the Suez Canal Authority lost an estimated USD 14 million in toll revenues for every day that the canal was blocked and some captains diverted their route thousands of kilometres around the Cape.2 While ships were brought to a standstill and labourers struggled to dig out the colossal Ever Given, it was images of inertia that rapidly circulated around the world instead of commercial goods, making conspicuous the impatience of capitalism. After six days of “Dredging, Tugging, Digging & Tweeting,” the suspension of the global shipping network displayed how the hyper acceleration of time and space at the planetary scale cannot be taken for granted.3

-

Motoko Rich, Stanley Reed and Jack Ewing, “Clearing the Suez Canal Took Days. Figuring Out the Costs May Take Years,” The New York Times, 31 March 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/31/business/suez-canal-ship-costs.html. ↩

-

Mary-Ann Russon, “The cost of the Suez Canal blockage,” BBC News, 29 March 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-56559073; Mia Jankowicz, “Ships stuck at the Suez Canal are taking a detour thousands of miles around Africa because of the container vessel blocking the way,” Business Insider, 26 March 2021, https://www.businessinsider.com/suez-canal-some-consider-detour-round-africa-as-ship-blocks-way-2021-3. ↩

-

@SuezDiggerGuy, “Dredging, Tugging, Digging & Tweeting is going well and will continue through the night. Shout out to all these folks working round the clock to pull this ship out of its misery.” Twitter, 21 March 2021, 4:52pm, https://twitter.com/SuezDiggerGuy/status/1375913730509303808?s=20. ↩

Within the planetary field, contested territories are archives of exploitation, violence, and speculation. The Suez Canal, connecting the Mediterranean Sea with the Indian Ocean, was to represent the unification of the globe.1 But we must remember that the excavation, completed in 1869, took ten years and claimed the lives of an estimated 120,000 workers (out of 1.5 million), who for five of those years were employed as forced labour.2 It was therefore at the scale of the body that colossal amounts of earth and stone were excavated, moved, and dredged. As Irish explorer Thomas Kerr Lynch writes of his 1864 visit to the construction site, “[i]f the quantity of earth or sand to be excavated were placed in gufahs one after another, they would form a line which would three times surround the world.”3 A product of geopolitical power struggles beyond its physical site, the canal was built and operated by the Universal Company of the Maritime Canal of Suez, which was incorporated under Egyptian law but whose majority, controlling shareholders were French and (as of 1875) British. Egypt finally nationalized the company in 1956, leading to the Suez Crisis in which Israel, France, and the United Kingdom invaded to regain control of the canal but withdraw due to political pressure. Not long after, a 1963 report commissioned by the United States Department of Energy advanced the ludicrous idea of excavating a parallel canal in neighbouring Israel by using hundreds of nuclear explosives4—part of Project Plowshare, a legacy of President Eisenhower’s 1953 “Atoms for Peace” campaign promoting peaceful and constructive uses for nuclear explosives.5 Indeed, the history of the Suez Canal is indicative of contemporary conflicts not only over goods and resources but also over the policies and technologies through which goods are conveyed.

As a way to counteract the magnitude of forceful planetary transformation while embracing the revelatory nature of scalar relationships, the 2020 edition of Toolkit for Today: In the Planetary Field, was framed by the assumption that architecture’s three dimensionality has often privileged and confined the practice to the scales of the building, neighbourhood, or city. As a counterproposal to how histories of architecture have been written, we (the Doctoral Research Residency Program participants) instead use objects, buildings, neighbourhoods, and cities as instruments of scale for encapsulating the magnitude of the planetary field. The stuck Ever Given is one such object: it is architecture, it is a calculable material handling system, and it is a piece of political infrastructure that refutes indeterminacy.

-

Valeska Huber, Channelling Mobilities: Migration and Globalisation in the Suez Canal Region and Beyond, 1869-1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 39. ↩

-

Thomas Kerr Lynch, A Visit to the Suez Canal (London: Day and Son, Limited, 1866), 45; Huber, Channelling Mobilities, 29. The use of forced labour (corvée) was abolished in 1864. ↩

-

Lynch, A Visit to the Suez Canal, 45. A gufah (also known by other names such as quffa or kuphar) is a sturdy, circular boat, resembling a bowl or basket, used to move people or goods by rowing or poling. ↩

-

H.D. Maccabee (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory), “Use of nuclear explosives for excavation of a sea-level canal across the Negev Desert,” report UCRL-ID—124767, U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information, https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/453701. ↩

-

Scott L. Kirsch, Proving Grounds: Project Plowshare and the Unrealized Dream of Nuclear Earthmoving (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005). ↩

In his theory of the accident, the French philosopher and urbanist Paul Virilio noted that an inherent condition of progress (namely, inventions) is destruction—the plane brings about the plane crash, the train carries with it the trainwreck, and so on. Such accidents, according to Virilio, reveal the “substance” of a thing and bring a latent quality to light.1 A shattered glass, for instance, reveals the fragility of the material and the intricate way light is refracted by the shards; this moment of supposedly unintended destruction, malfunction, or error exposes what has always existed yet has been hidden from sight. Applying Virilio’s object-oriented and phenomenological reading of the accident to the stuck Ever Given should, in theory, reveal some obscured quality of the freight ship, or perhaps of the canal itself. And yet what is revealed is not any unknown substance hidden, so to speak, within the ship’s hull, but rather the unseen entanglements of global supply chains and the ways in which these become, when revealed, entertainment for the world. What better representation is there for a global crisis—be it analogy, metaphor, allegory, or simple ruse—than a large and powerful bulldozer, normally able to manipulate and transform the environment, rendered miniscule and useless in comparison to the hull of an enormous ship it tries to dislodge. This image exposed not only the scale, or scalelessness, of the accident, but also our inability to grasp the actual size of an Ultra Large Container Ship (ULCS). As one writer noted, “The ship, which is longer than the Empire State Building is tall, looms over literally everything.”2 This strange comparison to a tower that has not been the tallest in the world since 1971 is indicative of our need to shift our own instruments of measurement and understanding.

Ironically, endless numbers, figures, and quantities—like those with which we began this text—simply produced an overwhelming inability to comprehend the gravity of the seemingly local event. A plethora of images followed instead. Memes of the futile digging process, screenshots of real-time maritime traffic jams, and comparative graphics of the Ever Given’s immensity were better able to scale into understanding the incalculable effects of a single blocked container ship on the global economy. And furthermore, the creation of images by countless users exposed, however inadvertently, the planetary scope of the audience and the variety of ways to comprehend scale. For instance, one graphic compared the length of the Ever Given to that of the Star Trek USS Enterprise.1 The comparison is not merely physical and quantitative, it is an attempt to use a fictional object—designed to defy and expand our cultural imagination of the final frontier—as a measure for a very real, terrestrial, mundane one. In another graphic, the height of the Ever Given is presented as “comparable to a 20-storey block of flats,” thus collapsing its enormity to the more easily understood domestic scale, from which the pandemic-stricken global audience was watching the scene unfold.2 In both cases, it required other points of reference, relatable or not, to measure an object that is so essential to global operations and daily life, yet is usually imperceptible. Indeed, today 90 percent of goods are transported by shipping container, itself a unit of commerce that makes the handling of goods odourless, invisible, anonymous, and abstract.3 Until the accident of the Suez Canal obstruction, we simply did not pay much attention.

As architect and architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay has argued, an aesthetic of bigness dominates our historical imagination.4 If we were irresistibly drawn to images of the drama at the Suez Canal, it’s perhaps because measurement translated into a visual metaphor speaks to our senses more than the tools of capitalist calculation ever could. The images of the Ever Given gave a scale to an otherwise abstract, residual mercantilist space. They revealed a territorial sublime—an experience that challenges the limits of an individual comprehension of geography—and reminded us of the megastructure of capitalism, within which the planet is a factory for manufactured goods and images.

-

Dan Hon (@hondanhon), “I just had to do the Enterprise D.” Twitter, 26 March 2021, 1:48pm, https://twitter.com/hondanhon/status/1375504867582611462?s=20. ↩

-

Michael Safi et al., “How a container ship blocked the Suez canal – visual guide,” The Guardian, 24 March 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/24/how-a-container-ship-blocked-the-suez-canal-visual-guide. ↩

-

Charmaine Chua, “The Container: Stacking, Packing, And Moving The World,” The Funambulist 6, Object Politics (July-August 2016); Allan Sekula, Fish Story, eds. Witte de With, Center for Contemporary Art and Barbera van Kooij (Düsseldorf: Richter, 1995). ↩

-

Swati Chattopadhyay, “Architectural History or a Geography of Small Spaces?,” (lecture, Society of Architectural Historians Conference, 15 April 2021), https://vimeo.com/537508419. ↩

This reflection (on what the Ever Given accident reveals) was written from distanced geographies via digital connections, during a time when our perceptions of the self and the world have been mutated and rescaled by the COVID-19 pandemic. Within this context, we interrogated what instruments of scale can be found in the history of architecture and urbanism. While scale has been widely used for translating dimension, the texts that will follow this introduction probe the temporal, geographic, material, and economic fields that have constituted the scale of the planetary—just like an individual sending a meme into a vast network of information or a single container ship halting the global economy. What planetary processes are revealed through the scale of a pond, an atom, or a plantation? Does an individual, a water droplet, a boathouse, or a postbox act as a measure for comprehending architecture? Can a reference number, a gesture, a cabinet, or a nation mediate the scalelessness of an archive? “In the scale of…?” is a provocation to consider how architecture is not only a complicit agent in scalar processes but also a tool of magnification to better understand the planetary field.

The illustrations presented in this article are all satirical, parodic, or press images published on Twitter, 2021.