Decolonize or Redistribute?

Abdel Moneim Mustafa and Mid-Century Modernism in Sudan

Esra Akcan examines architecture through the lens of healing from colonization

When I went to Abdel Moneim Mustafa’s old office with Migdad Bannaga in 2019, we found a large drawing cabinet. Thanks to the care and foresight of the current owners and employees in the office, Moneim Mustafa’s drawings have reached our day, but they were wearing out and getting unusable. As I took photographs of the rat-eaten drawings, I found myself increasingly agonizing about my own discipline’s collecting and preservation practices. How could someone as gifted as Moneim Mustafa, one of the most locally admired architects in Khartoum and the designer of some of the most exciting mid-century modernist buildings anywhere, be so neglected, so ignored out of Sudan, that to this day there is no internationally accessible publication in his name, and that his hidden and decaying drawings are guarded only by volunteers? For this reason, I was happy to become a liaison for the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s initiative to digitize these drawings, ensuring they do not leave Sudan or change owners and making them accessible to scholars and students from around the world for further study in an effort to find alternatives to colonial collecting practices.

After its independence in 1956 from Egypto-British colonization that had followed the Ottoman rule, Sudanese cities became a target of the soft power policies of the Cold War’s two Blocks. This condition was visible in the physical landscape as large, eye-catching buildings were built with the American Aid and as Chinese Gifts. It was in this context that Sudanese architect Abdel Moneim Mustafa achieved a sophisticated practice that translated locally and globally produced climate-specific and modernist know-how, while designing residences for the new Sudanese political leaders, as well as office and education buildings in Khartoum. In this paper, I bring new materials from the remains of Moneim Mustafa’s old office and the personal collections of his clients, students, and co-workers, as well as my own on-site analysis, to discuss the architect’s buildings through the lens of healing from colonization.1

Walter Mignolo sees the Asian-African strategic partnership at the 1955 Bandung Conference by independent nations as a “dewesternizing” movement against the two “westernizing ideologies of the Cold War.” But he also sees it as the first but ultimately failed step toward decolonization. Instead, he defines “decolonial thinking and doing” as that which “delinks from the epistemic assumptions common to all areas of knowledge established in the Western world since European Renaissance and through the European Enlightenment.”2 Recently, the term decolonization has been used generically without attention to geographic or historic context—a phenomenon that Eve Tuck and Wayne Yang have also criticized in an inconclusive article where they put into further crisis any metaphorical understanding of decolonization.3

As intriguing as they might be, I will argue that the above ideas on decolonization do not provide the theoretical framework from which one could appreciate the critical work of the early Independence Era figures such as Moneim Mustafa. Instead, I would like to suggest redistribution as a distinctive approach to post-colonial right-to-heal in the context of Cold War bi-polarities.

While this constitutes the paper’s theoretical framework, an additional historiographical aim is to put the neglected Ottoman Empire into the histories of Afroeuroasia. What is missing in the standard histories of colonization and decolonization of Africa, which often treat the continent as a separate and singular land whose nations gained independence and territorial sovereignty after being colonized by Western European powers? One of my historiographical aims is to examine the competitive imperialisms and extractive economies running between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea in order to go against the grain of the current academic compartmentalization. This will allow a more layered account of the Cold War than one focused solely on two superpowers, and a more truthful version of postcolonial struggles in Africa due to the professional networks that descended from the Ottoman Empire, as well as the resettlements of ex-Ottoman populations during the long wars at the first quarter of the twentieth century.4

-

I would like to express my gratitude for Migdad Bannaga, Mustafa’ office Technocon, Adil Mustafa Ahmad, Salah Hassan, Amira Swar-El-Dahab, Osman M. El Kheir, Elamin Osman, and Ilham Abdalla Tagelsir Ali for helping me reach these private sources and archives in Khartoum. I would like to thank the habitants of the private residences for opening their doors to me, especially Mansour Khalid, Bedridi Suleyman, Mahmood Abdelrahim, and Al-Safi family. The research in Sudan was complemented by research in Doxiadis Archives in Athens (special thanks to archivist Giota Pavlidou), Ottoman and SALT Archives in Istanbul (thanks to my research assistant Aslihan Günhan), Canadian Centre for Architecture in Montreal, as well as the libraries of Harvard and Cornell Universities in Cambridge and Ithaca. ↩

-

Walter Mignolo and Catherine Walsh, On Decoloniality: Concepts Analytics Praxis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 106. ↩

-

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a Metaphor,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education& Society Vol.1, No.1, (2012):1-40. ↩

-

Esra Akcan, “After the ‘Last Ottoman Generation’: Sudan at Colonial and Postcolonial Crossroads,” paper in Empire’s Province into National City: Architecture and the Dissolution of the Ottoman Empire symposium convened by Esra Akcan and Peter Christensen, Cornell University-University of Rochester, 14-15 March, 2022, Ithaca-Rochester, USA, supported by the Central New York Humanities Corridor. ↩

To navigate these ambitions in a short paper, I will anchor the discussion on the verandah as a designed architectural and urban space.

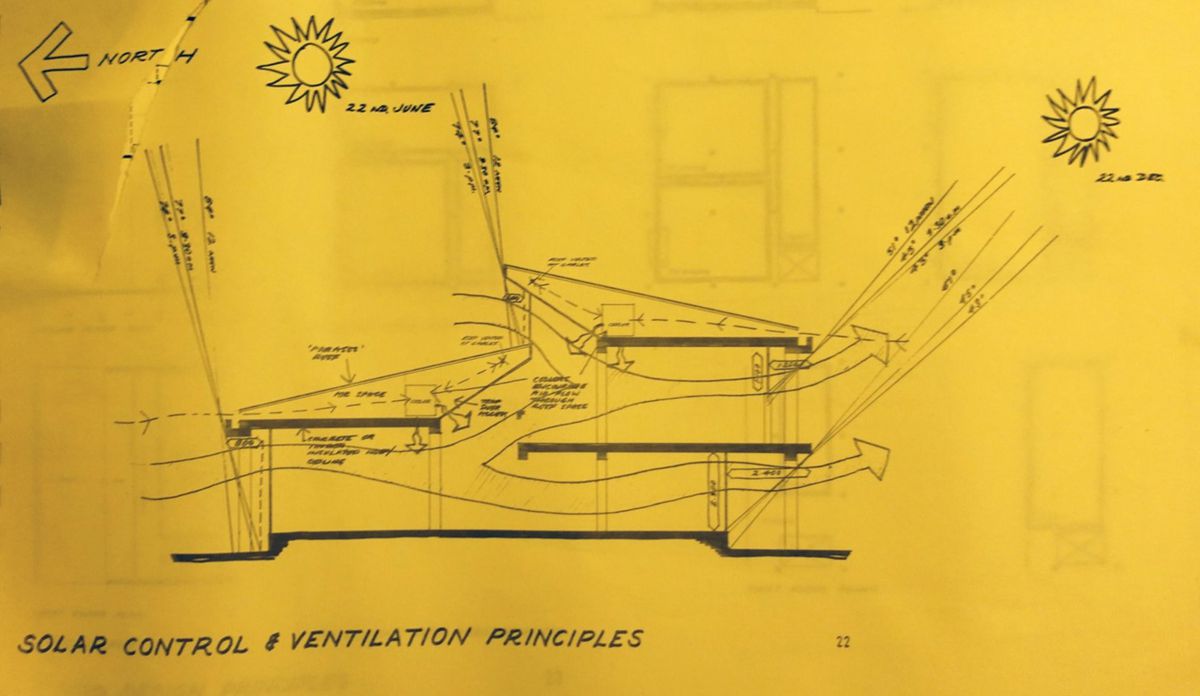

Despite the lack of published recognition, Moneim Mustafa is one of the most locally admired Sudanese architects of his generation. His buildings in Khartoum can be easily identified with their distinct details and climate control techniques. The private houses, most of which were commissioned by the new statesmen, professionals, and rising bourgeoisie of Sudanese independence, are modular reinforced concrete frameworks filled with variations of solids and voids, programmed as multiple types of verandahs and interior spaces. Moneim Mustafa’s concerns for climatic accommodation provided the most memorable metropolitan structures of Khartoum, such as the Al Ikhwa Tower where large balconies are not only stacked for sun-shading but also switched for air circulation. These concerns translated into signature window details in larger office buildings such as the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa, the Industrial Development Bank, the Sudanese Savings Bank, and the Public Social Insurance Institution. Sunlight enters these buildings in very controlled ways through sun-shading devices and double surfaces. With the Al Merrikh Stadium, Moneim Mustafa focused on digging down the ground rather than building up, and was thus able to insert the building gently into the city fabric despite the grand area it covers, rather than intervening with an aggrandized monumental structure. His collaborations in the University of Khartoum where he taught, as well as his own campus and neighborhood designs, participated in the mid-century modernist transformations in greater Khartoum. In each and every one of these buildings, Moneim Mustafa took sun control and ventilation into the centre of urban and architectural design, and intentionally translated what was named “tropical architecture” in empowering ways. Many of the drawings of private residences, collective housing, and office buildings have now been digitized and catalogued. In these drawings one can see Moneim Mustafa using nomenclature such as verandah, courtyard, mastaba, terrace, and lawn denoting different types of outdoor living space. The section drawings also provide evidence for the careful design of window details.

To decode this approach, let me go back in time, and trace these architectural elements and terminology by bringing documents from colonial and Cold War archives.

Khartoum—a city at the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile—is fraught with the militaristic and segregation policies of its British colonial master plan. Upon conquest in 1898, General Kitchener laid a plan of Khartoum across from the existing towns of Omdurman, North Khartoum, and the Tutti Island. The plan juxtaposed a gridded-street layout over the small fortressed Ottoman military settlement, and defined large blocks cut diagonally with large avenues. In 1912, W.H. McLean extended this master plan under the direction of Kitchener with similar street patterns and by explaining the origins of the colonial grid as a military invention that posited the British Empire as the heir of the Roman Empire: “It is interesting to take this ‘grid-iron’ plan, which was doubtless the design initiated by that great soldier Alexander, and to note its similarity to the plan of Khartoum, which, more than two thousand years later, was initiated by that great soldier of the late Lord Kitchener.”1 To justify his colonial ambitions, McLean relied on the Orientalist accounts of travelers in the 1850s and 1860s,2 and described the pre-Ottoman and Ottoman Khartoum as a “miserable, filthy and unhealthy” town composed of “primitive houses” and “impassable streets,” which “remained in ruins until the reconquest of the country by Lord Kitchener in 1898.”3 Kitchener and McLean also safeguarded the segregation of the local and British habitants, by placing their morphologically different urban zones in different banks of the river and justifying this difference with the alleged racial adeptness to tropical climatic conditions. “As a general rule,” McLean said, “it is well, if possible, to segregate the population, as the epidemics to which all tropical cities are liable can be so much more easily dealt with.”4

The term and expertise of tropical architecture has colonial origins. McLean clearly expressed the need for proficiency in tropical architecture in order to protect the British citizens, whom he differentiated from “natives” due to their skin color: “It has been shown that the greatest enemy of white men in the tropics is the sun, and that the effect of tropical light on such men is injurious, causing nervous and other diseases. The native of tropical regions being highly pigmented is protected naturally from the harmful rays of sun, so that he is in perfect adjustment with his environment.”5 McLean thus proposed to segregate the “white” and “native” people “so that zones may be arranged as far as possible to the requirements of the various sections of the population,” and that “Europeans live in houses so arranged as to be exposed to the prevailing winds… surrounded by gardens or open spaces to permit the free circulation of air,” even though “the natives can live comfortably in much more crowded circumstances.”6 This premise about human difference and European comfort in a perceived tropical climate resulted not only in the racial segregation of populations in Omdurman and Khartoum town, but also in the latter’s construction with wide streets on a grid-iron plan and large blocks that produced very low density.

McLean extended his views on tropical city planning to architecture, and endorsed the verandah as the most appropriate architectural element, both to protect the walls from the sun and as a covered outdoor living space.7 The verandah became the most identified and designed element of colonial architecture, suggested by the colonial office for typical residential plans, and used in private houses with colonnades and column capitals. The verandah was the identifying space in iconic and strategically placed buildings of the colonial era as well, such as the Holiday Villa (designed by G.E. Francis), where many colonial officers stayed and held meetings,8 the Omdurman Municipality (designed by Derek Matthews, the Sudan Club, the Kitchener Memorial Medical School (designed by G.B. Bridgman), and the Gordon College—today’s University of Khartoum—where Moneim Mustafa and his generation made many additions. The first building of the university was originally designed by the Ottoman-Greek architect Dimitri Fabricius after being employed by the Ottoman Khedive in 1900, and completed soon after the British colonization. 9 After WWII, the London-supervised Public Works Department commissioned W.G. Newton to prepare the master plan for the university’s extension.10 His explanations prove that the verandah had continued to be perceived as the most appropriate space for tropical architecture due to its sun shading and ventilation advantages. “The walls most in danger of heating up” were to be “shaded with verandahs,”11 in compliance with “the two conditioning factors of most importance: a. the heat and glare from sunshine, b. north to south and south to north currents of air.”12

-

W.H. Mc Lean, Regional and Town Planning (London: Crosby Lockwood and Son, 1930), 62. ↩

-

These include George Melly, Khartoum, and the Blue and White Niles (London, Colburn & co., 1851); John Petherick, Egypt, the Soudan and Central Africa: With Explorations from Khartoum on the White Nile, to the Regions of the Equator; Being Sketches from Sixteen Years’ Travel (London, 1861); Sir Samuel Baker, The Albert N’Yanza Great Basin of The Nile; And Exploration of The Nile Sources (Detroit, Negro History Press, reprint 1970, original 1866). ↩

-

McLean, Regional and Town Planning, 68. ↩

-

W.H. McLean, “Town Planning in the Tropics: With Special Reference to the Khartoum City Development Plan,” The Town Planning Review, vol.3, no.4 (Jan. 1913): 225-231; quotation: 225. ↩

-

McLean, “Town Planning in the Tropics,” 225. ↩

-

McLean, “Town Planning in the Tropics,”, 225-26. ↩

-

McLean, “Town Planning in the Tropics,”, 230-31. ↩

-

Designed by the British A.R.I.B.A architect G.E. Francis, and supervised by Public Works Department of Sudan Government. The drawings were prepared by the local staff recruited from Gordon College, “The Grand Hotel, Khartoum,” Builder vol. 141, no. 8 (1931): 342. ↩

-

“Gordon Memorial College, Khartoum, scheme for redevelopment,” Builder, no.1-11 (1946): 36-38; “Gordon Memorial College, Khartoum” Builder, vol. 181, no. 7 (1951): 4-6. ↩

-

He added the new brick hostel buildings (today faculties) on two sides of the main alley, as well as an open-air theater, library, and mosque. ↩

-

“Gordon Memorial College, Khartoum” Builder, vol. 181, no. 7 (1951): 4-6; quotation 5. ↩

-

The architect continued with other climate-control techniques: “The rooms in the hostels have windows which open into high porches in such a way that much of the glare is kept out of the rooms. Also, these porches canalize the two prevailing air currents. The windows, further, have an arrangement of shutter-scoops, to catch these air currents as they pass.” In “Gordon Memorial College, Khartoum, scheme for redevelopment,” Builder, no.1-11 (1946): 36, 38. ↩

Soon after Sudan’s independence from British colonization in 1956, a cohort of planners and architects including Moneim Mustafa aimed to mark this transition with new planning and stylistic revisions. Among them, the Doxiadis Associates undertook the master plan of greater Khartoum in 1959, and collaborated with Moneim Mustafa’s office Technocon for a second plan of 1990. The soon-to-be prolific Greek architect Doxiadis referred to Khartoum as the first city that accepted his idea of “Dynopolis.” In his lectures in and on Sudan, Doxiadis advocated the developmentalist zeal of a Weberian-type modernization theory as the calling of Independence.1 Moneim Mustafa shared some of the developmentalist enthusiasm of the time. He referred to his project for the unbuilt College of Fine and Applied Arts2 as “an essential instrument for economic development and social change, …and a cultural center where the public can meet with the staff and students to discuss, exchange ideas and to evaluate imaginative and inventive contributions in the light of [Sudan’s] realities and future prospects.” 3 Moneim Mustafa identified “flexibility and extendibility” as the major planning principles of development,4 and sketched alternative schemes such as the monocentric, polycentric, grid iron, and linear models.5 The campus facilities were arranged on spines so that the art studios could expand 50%, while the hostels 200%.6

Doxiadis Associates proposed significant changes to Khartoum’s colonial master plan without necessarily exposing its racist and militarist colonial policies. Throughout his career, Doxiadis diagnosed problems of world cities as challenges brought by industrialization, but did not identify colonization as an additional historical burden on ex-colonial cities. Without naming it, the Doxiadis team found the British General Kitchener’s colonial grid as the cause of land settlement problems. The office made a case for the master plan of the greater Khartoum area in which they proposed to combine the colonial town of Khartoum with Khartoum North and Omdurman. For the purposes of this paper, it would be good to note that they proposed to add new transportation networks, to construct five arterial roads and two new bridges (which were built by Moneim Mustafa’s office Technocon years later, and to move the airport to North Khartoum (which never happened but for a design of which Moneim Mustafa collaborated with Italian architects Paolo Portoghesi and Vittorio Gigliotti in 1973).7

-

For more on Doxiadis and Sudan, see, Esra Akcan, Abolish Human Bans: Intertwined Histories of Architecture (Montreal: Canadian Centre for Architecture, 2022). ↩

-

The College included Departments of History and General Studies, Basic Design, Drawing, Pottery, Sculpture, Industrial Design, Textile, Painting, Graphics, Calligraphy, and Printing, with future concentrations on Kilims and Materials, Printmaking, Gold and Silver smiting, Costume and Dressing, and Textile Design Production. ↩

-

Abdel Moneim Mustafa, Ayoub, and Omer Salim, “College of Fine and Applied Art, Khartoum Polytechnic Sudan,” Reports 1 and 2. I located these documents from the remains of Mustafa’s office in Khartoum. Author’s collection. Quotation: Report 1, p.1. ↩

-

He referred to campus planning as the urbanism of a “small town,” Mustafa, Ayoub, and Salim,. Report 1, p.2. ↩

-

“Flexibility and Extendibility: Since development can involve change of use, alteration of existing facilities or extension, these appropriate planning should allow for: a. Flexibility which means that the PLAN can accept changes. B. Extendibility which means that the PLAN should allow for necessary additions and future expansions.” “The common principal planning models include monocentric, the polycentric, the grid iron and the linear type. The challenge is the chose the model that satisfies best the stated basic planning principles while bearing in mind the site analysis and requirements. In general, it appears that the linear model that yields a strong relationship between the central facilities and the teaching departments while allowing for a reasonable expansion of both functions, is the most suitable development hypothesis which will guide development and ultimately define the physical environment.” Mustafa, Ayoub, and Salim, Report 1, p.26-27. From alternative development patterns, Mustafa chose the linear extension as the “most suitable development hypothesis which will guide development and ultimately define the physical environment.” ↩

-

Mustafa, Ayoub, and Salim, Report 2, p.1-2. ↩

-

Christian Norberg-Schulz, “Locus: opera di Paolo Portoghesi e Vittorio Gigliotti,” Controspazio vol. 7 no 4 (December 1975): 40-79. Schulz does not credit Mustafa’s office, but the drawings can be located in his archive. ↩

Doxiadis’ situatedness in relation to Sudanese postcolonial struggles, and by extension to Moneim Mustafa, is quite complex. The Greek community in Sudan had reached about 7000 by his arrival after exponentially growing during Ottoman and British colonization, due to both trade and slave-trafficking, and to Greek-Turkish population exchange.1 Many ethnically Greek builders of the Ottoman Empire had worked to construct important buildings and structures,2 and some Khartoum-born Greeks such as Georges Stefanidis designed the earliest modernist public buildings in the city’s prestigious locations. Doxiadis continued to use such connections so that the Sudanese government agreed to implement his plans.3 Moreover, archival documents expose that Doxiadis was closely connected to American soft power policies, and in communication with the American Embassy in Sudan to which he sent reports on Sudan, Pakistan, and Lebanon.4 The American Aid provided funds and assistance for many of the major public buildings in Khartoum, such as the iconic ones built by the Greek-Austrian architect Petermuller, who stayed for a decade-long productive career. American Aid also funded the Public Works Department that employed Moneim Mustafa after he returned from the United Kingdom, where he had received a fellowship to study architecture.5

-

Antonios Chaldeos, “Sudanese toponyms related to Greek entrepreneurial activity,” Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies, Vol. 4 , Article 4 (2017): 183-195; G.P. Makris and Endre Stiansen, “Angelo Capato: A Greek Trader in the Sudan,” Sudan Studies, no. 21 (April 1998): 10-19; “Greeks in Sudan” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greeks_in_Sudan Accessed 1/31/2021. ↩

-

Evangelia Georgitsoyanni, “Greek Masons in Africa: the case of Karpathian Masons of Sudan,” Journal of Hellenic Diaspora vol. 29, no. 1 (2003): 115-127. ↩

-

He wrote letters to Messrs Conromichalos and Antachopoulos in Sudan. Doxiadis Archives. ↩

-

Doxiadis to Stephen Dorsey, Counselor to American Embassy of Sudan, 11.9.59 (C-OA 120); Doxiadis to Stephen Dorsey, Counselor to American Embassy of Sudan, 12.10.1959 (C-OA 128), Sudan Correspondence C-OA 28-441. Administrative Circulars A-OA 1-4 1959—1962, 24827, vol. 6. Doxiadis Archives, Athens. ↩

-

Moneim Mustafa started learning engineering in the University of Khartoum, where there was no architecture department. He received a fellowship to continue his education in U.K. Interview with Abdol Moneim Mustafa’s partners (Technocon), Yahya Muhammasalieh and Professor Abu Bakir Abdulrahab, 22 December 2019. ↩

Khartoum professionals often mention Petermuller and Moneim Mustafa together, as the two architects shared many aesthetic and functionalist sensibilities. Both translated verandahs and sun-screening devices into a new modern architectural language in conversation with the international currents of their time. While designing private houses, Petermuller placed the buildings in open spaces and provided ample verandahs just like the colonial architects, but with highlighted reinforced concrete columns and extended beams rather than the classical colonnades of the colonial period. Having designed many private houses, Moneim Mustafa’s career accumulated in a rich set of variations of verandahs, terraces, and sunscreens, all expressed in modular reinforced concrete frames. These houses provide a network of open, covered, screened, and closed spaces for the climate-control of different activities, including open-air sleeping terraces for the night, and shaded socializing spaces for the day. Moneim Mustafa used verandahs both as living areas attached to interior spaces and as circulation paths that were part of the landscaping of gardens. Mahmood Abdelrahim House in Khartoum integrates high street walls into the design that create a courtyard behind, just like Omdurman’s houses; whereas Bedridi Suleyman House in North Khartoum is a freestanding object in a large spacious garden without street walls. Mansour Khalid’s house creates a hybrid relation with the street due to its lifted verandah from where one can see behind the high garden wall. The trees consciously planted outside the solid walls of the Double house in Omdurman both protect the house from over-heating and provide a shaded and paved meeting place on the public street. In his designs for less wealthy collective housing, Mustafa made sure to provide a verandah for each unit, regardless of the modest means. The full set of drawings for “Neighborhood Design” with perspectives of typical houses with verandahs have now been digitized with CCA’s support.

These gestures were carried to public buildings as well. In the Chemistry Lab of the Faculty of Science in the University of Khartoum, Petermuller lifted the entire multi-story building from the ground in order to create a meeting place for students. Today, the area functions as a shaded public space as well as a passageway that links parts of the campus. The memorable verandahs of this building, with tilted wooden grid latticework, protect the walls from the sun and regulate the linear and vertical circulation spaces with impressive shadows on surfaces. The verandah-in-the-air functioning both as a sun-shading device and a socializing circulation space, as well as the most identifying façade element became a repeated pattern during this time. In the Faculty of Architecture, designed in four phases by different faculty members, a protected outdoor circulation network combines programmatic spaces and different levels by also knitting the separate buildings together.

Now, there is a significant quality that differentiates Moneim Mustafa from his predecessors and cohorts, and shows his corrective participation in the “tropical architecture” proficiency. This difference can best be illustrated by comparing Petermuller’s and Moneim Mustafa’s campus designs. In Khartoum Senior Trade School (today’s South Campus of University of Sudan), Petermuller followed the British colonial planners’ assumptions about the need for large open spaces in between buildings that would generate wind flows and ventilation, and thus considered a site plan composed of freestanding modernist blocks as a viable solution. The tropical architecture discourse with its British connections went through some transformations, but continued to inform the architects in Khartoum. During the mid-twentieth century, new medical conceptions had replaced the colonial theories of disease transmission. Previously, McLean had suggested racial segregation to contain epidemics, which was no longer a viable theory, but the tropical architecture know-how nonetheless persisted. In Jiat-Hwee Chang’s words, “living in the tropics was no longer a matter of life and death [for the British]. It was more a matter of thermal [bodily] comfort.”1 In the pages of Colonial Building Notes (name changed to Overseas Building Notes in 1958), as well as the Tropical Architecture program in London’s AA school founded by the Colonial Office, tropical architecture became a discipline of scientifically tested climate-control techniques.2 Sudanese students were hosted3 and examples studied in these venues.4

-

Jiat-Hwee Chang, A Genealogy of Tropical Architecture: Colonial Networks, Nature and Technoscience (London, NY: Routledge, 2016), 185. ↩

-

For more on AA and tropical architecture, see: Vandana Baweja, “Otto Koenigsberger and the Tropocalization of British Architectural Culture,” in Duanfang Lu (ed.) Third World Modernism: Architecture, Development and Identity (New York: Routledge, 2011): 236-254. ↩

-

Students from Sudan were also educated in AA, such as Moneim Mustafa’s student, the prominent scholar and teacher Adil Mustafa Ahmad who joined the school to study with Otto Koeningsberger. ↩

-

One example is Y.A. Mukhar’s article that asserted to scientifically certify the effectiveness of the double roof system in Petermuller’s campus design. Y.A. Mukhar, “Roofs in Hot Dry Climates with Special Reference to Northern Sudan,” Overseas Building Notes, No. 182, October (1978): 1-15. ↩

However, Sudan’s place in the field of tropical architecture was premised on a foundational miscategorization. British colonizers mistook all of their colonies as tropical lands in an overarching umbrella that spanned from Libya to Malaysia, from Saudi Arabia to Hong Kong. A map published in a 1955 issue of Colonial Building Notes exposes the lingering effects of this colonial epistemology and identifies the tropical zone in relation to geopolitical borders, rather than Mercator lines. The entire continent of Africa and countries in West Asia, Asia, and South America were identified as tropical areas even when they were situated on the same latitude as some European countries and North American states.1

Instead, Moneim Mustafa corrected the British nomenclature by identifying Khartoum as “hot dry tropical,” and warning additionally against the “strong dust storms that reduce vision and create disagreeable working conditions.” In his report for the College of Fine and Applied Arts, he continued: “Such climate conditions call for maximum efforts to improve micro-climate of the site. Buildings should be oriented in the east-west axis. They should be grouped around courtyards of green lawns and thick trees. Open grounds and fields should be planted and made green to reduce the strong sun glare. Uncovered links between buildings should be as short as possible.”2 While Petermuller designed many open-air areas in between buildings, Moneim Mustafa made sure to avoid uncovered walkways in a tightly knit network of buildings. His site plan was as informed by the traditional precolonial urban fabric of Omdurman, as it was by the technical information of the tropical architecture discipline. Based on programmatic relation diagrams, he designed shared courtyards and verandahs between different art departments, which would additionally foster interdisciplinary dialogues. Student hostels were to provide 50% outdoor sleeping possibilities in the form of terraces and verandahs, and landscaping was to play a vital role for the creation of the microclimate, the shading of cars, and the providing of different identities to courts.

Mustafa continued drawing from the technical know-how that he had gained through the tropical architecture discipline. He used solar diagrams, drew sections of sun and wind control, and explained that climatic concerns “led to a sectional development” which provided north light for studios, and indirect sunlight from the south that entered the building only through a shaded walkway area. The roof with concrete slabs assisted the ventilation with what he called a parasol system and desert coolers.3

-

Colonial Building Notes 32 (September 1955):7 ↩

-

“led to a sectional development running east-west providing north light as the major source and supplemented by south light from a deeply shaded walkway area. All windows are totally shielded by overhead and flanking walls from receiving direct rays of the sun. The sectional form uses identical trusses resting on concrete slabs providing a location within a ‘parasol’ roof system for the siting of simple desert coolers which in turn mechanistically assist the roof space ventilation.” Abdel Moneim Mustafa, Ayoub, and Omer Salim, “College of Fine and Applied Art, Khartoum Polytechnic Sudan,” Report 1, p. 8. Author’s Collection. ↩

-

Mustafa, Ayoub, and Salim,, Report 2, p.2. ↩

What can we conclude from the history of the verandah as it reached Moneim Mustafa’s buildings? As we have seen, the verandah was a British colonial architectural device used for cooling purposes and British comfort in perceived tropical climates. Of course, there is nothing inherently colonial in passive climate control in architecture. As a matter of fact, local builders and architects had already developed many of these techniques for centuries and continued to improve them after independence. Moneim Mustafa himself was integrating precolonial space-making norms when he designed courtyards and mastaba spaces. What is remarkable in the history of the verandah in Sudan is that its colonial connotations were transformed after Sudanese independence. This was possible due to architects’ creative use of verandahs, for which they employed the technical know-how and sun diagrams progressed under the field of tropical architecture in the lands of ex-colonizers.

Was Moneim Mustafa failing to decolonize Sudan, in Mignolo’s sense, by using and naming spaces with colonial terminology, and by making use of the technical know-how associated with colonizers’ schools? When I presented Moneim Mustafa to European and North American architectural history networks in April 2021, I encountered a resistance and trivialization along these lines. Comments implied that Moneim Mustafa was not doing enough to stay outside a global economic system that relied on unequal development, or that he was too open to outside influences that invited backlash. Needless to say, Moneim Mustafa was living and working in a global financial exchange network that sustained colonial lines, and in a geopolitical world order that planted seeds of new injustices. The Islamist military officer Omer al-Bashir came to power in 1989 as an indication of what might be called the currency of the backlash. Sudan was swept with two civil wars that resulted in the genocide of Darfur and the separation into two countries. The greater Khartoum area is periodically distressed with flashfloods and refugee settlements, as well as the misplacement of the airport and railways. It is important to remember that some of these problems had been predicted by Moneim Mustafa’s generation and collaborators. After al-Bashir’s rise, Moneim Mustafa could no longer find public commissions, and eventually left Sudan. His symbolic buildings such as Mansour Khalid’s house were occupied by military powers. The struggle of the democratic forces against the military dicta is still ongoing. In this context, we need to find explanations that establish a critical distance from both external colonization and internal repression.

That was why, during my presentation in April 2021, I offered redistribution as a different form of healing struggle in postcolonial contexts. Against the standard view of decolonization as the “rejection of alien rule and the formation of nation-state,” Adom Getachew, for one, recasts a set of black Anglophone intellectuals’ work as that of a new, more equitable internationalism that struggled for self-determination to undo the domination of global empires but not at the expense of cosmopolitan ethics.1 Associated with broader political formations, including the non-aligned movement that sought to constitute a post imperial world order through Afro-Asian solidarity, this type of anticolonial struggle aimed to construct the conditions for international nondomination for an egalitarian but still a globally connected world order. Moneim Mustafa lived during Sudan’s transition from the colonial regime into the national one, where many professionals were connected to each other through a network that reached not only the British colonial architects but also the last ethnically Greek architects of the Ottoman Empire whose subsequent generation was now part of the American Aid of the Cold War period. Rather than blindly refusing or accepting the colonial heritage or American developmentalism, Moneim Mustafa rationally chose the functioning climate-control techniques from the imperial know-how, and translated them into his own building designs to be inhabited by the new Sudanese citizens. He also rationally chose to disuse some of these techniques in his urban designs, when he assessed their dysfunctionality from the viewpoint of climate control, and translated instead from the traditional settlement morphologies.

This freedom to choose, I would say, should be called independence, or self-determined interdependence, which redistributes the material and symbolic wealth produced during colonization among the newly self-governing citizens, rather than cancelling it in the name of decolonization. I therefore suggest to theorize Moneim Mustafa’s architectural position as redistributive justice to undo some of the colonial inequalities during the transition from colonization. This, I hope, gives due acknowledgment to the works of a gifted architect.

-

Adom Getachew, Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2019). ↩

This essay was presented at the Society of Architectural Historian’s (SAH) Annual Meeting in April 2021 for the panel “Building Non-Alignment” chaired by Vladimir Kulic and Amit Srivastava. As this presentation fostered the CCA’s connection, I kept the main arguments of the unpublished paper as a historical record, but added passages pertaining to the digitized drawings and questions following my presentation at SAH. This ongoing research is part of a book that explores architecture’s role in healing societies after conflicts and disasters by discussing buildings and spaces in relation to transitional justice and energy transition.