In the Scale of... a Reserve, a Plantation, an Artificial Pond

Magda Milosz, Robin Honggare, and Émélie Desrochers-Turgeon

This is the third installment of “In the Scale of…,” a series of counterproposals to conventional constructs of scale, authored by the participants of our 2020 Toolkit for Today and introduced by Émélie Desrochers-Turgeon and Eliyahu Keller in this article. In the following texts, Magda Milosz studies reserve boundaries imposed on the Coast Salish Peoples, Robin Honggare discusses what colonial-era photographs of Indonesian plantations reveal, and Émélie Desrochers-Turgeon considers what practices are implied by the demarcation of seemingly natural features. Each author considers how a framing device determines which histories of the transformation of land are rendered visible.

In the Scale of a Reserve

Magda Milosz

The land surrounding Burrard Inlet, in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, is part of the unceded territories of the Coast Salish Peoples. On the inlet’s south shore lies the city of Vancouver, while across the water four reserves line its north shore: three belong to Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation) and one to səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh Nation). The four reserves coincide with the pre-existing communities of Xwmel̓ch’stn, Eslhá7an, Ch’ich’elx̱wi7ḵw, and səlilwətaɬ. They are also part of Greater Vancouver, lying within the municipal boundaries of the District of North Vancouver, the City of North Vancouver, and the District of West Vancouver. These overlapping geographical, legal, and urban conditions are part of what might be called the scale of the reserve.

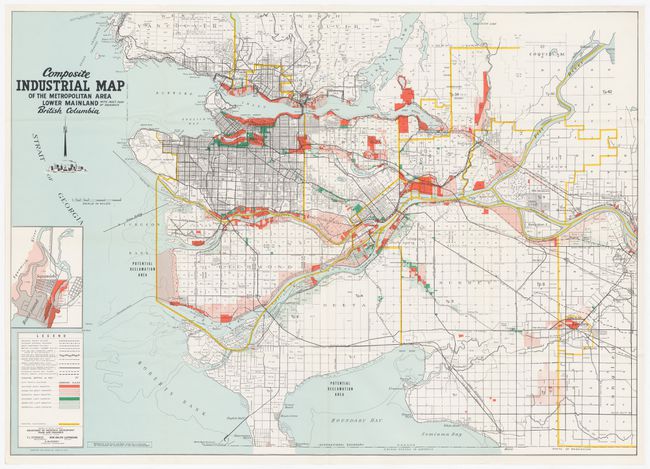

“Composite Industrial Map of the Metropolitan Area, Lower Mainland, British Columbia,” 1968. Reprographic copy, 81 x 114 cm. ARCH285194, Van Ginkel Associates fonds, CCA. Gift of H.P. Daniel and Blanche Lemco van Ginkel.

The map can be found in a folder with the proposal, correspondence, and terms of reference for a 1968 development study and plan of the four Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh reserves by Van Ginkel Associates Ltd. and engineering firm Kates, Peat, Marwick & Co. The map shows Burrard Inlet directly to the right of the title. The reserves on its north shore, outlined in black, overlap with various municipalities and industrial uses.

In Canada, reserves constitute miniscule fractions of Indigenous peoples’ territories. They were surveyed mainly in the nineteenth century to clear the way for mass Euro-colonial settlement. Legally, they represent spaces of circumscribed First Nations jurisdiction nested within the geographical and legislative borders of the settler state.1 While most are located in rural and remote areas, those in or near cities have usually become urbanized, obscuring the boundary between reserve and city, or else erased through expropriations and evictions. All Canadian cities, as Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar, writer, and artist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson reminds us, are built upon Indigenous lands.2 Yet settler-colonial urbanism has frequently operated to expel Indigeneity, and specifically reserves, from urban space. The early-twentieth-century expropriations of the Lekwungen reserve in Victoria and the Squamish community of Sen̓áḵw in Vancouver’s Kitsilano neighbourhood are just two examples.3 On Burrard Inlet, Xwmel̓ch’stn and Ch’ich’elx̱wí7ḵw came under similar settler-colonial pressures when the North Vancouver City Council asked the McKenna-McBride Royal Commission in 1915 that the reserves “be sold or leased on favourable terms for industrial sites.”4

-

See “Indian Act,” R.S.C., 1985, c. I-5 § 2 (1) (2019), https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/I-5/FullText.html. ↩

-

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance (Minneapolis; London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 173. ↩

-

Renisa Mawani, “Legal Geographies of Aboriginal Segregation in British Columbia: The Making and Unmaking of the Songhees Reserve, 1850–1911,” in Isolation: Places and Practices of Exclusion (London; New York: Routledge, 2003); Khelsilem, “A People United: How the Squamish People Founded the Squamish Nation,” The Coast Salish History Project, 23 July 2021, https://www.coastsalish.org/squamish-amalgamation-1923. The government later returned 11.7 acres of reserve land at Sen̓áḵw as part of a 2001 settlement. ↩

-

Quoted in Khelsilem, “A People United.” ↩

“Burrard Inlet Tunnel & Bridge Co., Plan showing part of Squamish No. 2 Seymour Creek Reserve required for railway purposes,” January 1911. 78903/45, Library and Archives Canada.

The relation of reserves to urban space has often been one of continuous appropriation. Here, the Burrard Inlet Tunnel & Bridge Co. marks off a portion of Ch’ich’elx̱wi7ḵw for a railway.

In 1968, the Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh Nations undertook a development study and plan for the four Burrard Inlet reserves, a process mediated by the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. The Terms of Reference for the project described the reserves as “some of the most valuable real estate in the lower mainland.” It continued, “Their strategic location combined with the growing scarcity of large acreages in this area make these reserves ‘ripe’ for development.”1 The framing of reserves in the language of real estate development, albeit in the “long term interest” of the two First Nations, suggests a desire to change the scale at which they operate. From longstanding Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh communities, overlayed with the colonial remnants of survey boundaries, the project ostensibly aimed to integrate them physically and economically with the surrounding urban agglomeration.

-

“Terms of Reference for a Land Use Study on Four Indian Reserves and Lot 5221 Group 1 N.W.D. (Indian Cut-Off Lands),” 1, 1968. Van Ginkel Associates Ltd., Indian Reserves—Burrard Inlet, Vancouver, 1967–1968. AP027.S1.D44, Van Ginkel Associates fonds, CCA. ↩

Photocopied map of West and North Vancouver, 1968. Reprographic copy, 21.5 × 35.5 cm. ARCH285195, Van Ginkel Associates fonds, CCA. Gift of H.P. Daniel and Blanche Lemco van Ginkel.

This map was filed with other materials relating to the 1968 proposal for the development of the four reserves on Burrard Inlet by Van Ginkel Associates Ltd. and Kates, Peat, Marwick & Co. Xwmel̓ch’stn (Capilano No. 5), Eslhá7an (Mission No. 1), and Ch’ich’elx̱wi7ḵw (Seymour Creek No. 2) have been outlined by hand.

The Squamish Nation today generates tens of millions of dollars of annual revenue through leases and taxes on commercial and residential tenants on its reserve lands.1 It also has large-scale residential projects in the works, including affordable housing for its members on Burrard Inlet as well as an impressive rental and strata development on the south shore, on the reclaimed Kitsilano No. 6 reserve at Sen̓áḵw. The ongoing neoliberalization and privatization of the quasi-communal ownership of reserve lands, particularly in urban conditions, has deep historical roots. Scholars like Julie Tomiak and Shiri Pasternak have problematized these processes as marked both by settler colonialism and by Indigenous self-determination.2 In the past, the fragmentation or wholesale erasure of urban reserves was driven largely by settler-colonial economic interests. Today, the situation is more complex, as First Nations attempt to reclaim reserves, themselves colonial creations, and incorporate them into a different scale of resistance.

-

Khelsilem, “A People United.” ↩

-

Shiri Pasternak, “How Capitalism Will Save Colonialism: The Privatization of Reserve Lands in Canada,” Antipode 47, no. 1 (2015): 179–196; Julie Tomiak, “Contesting the Settler City: Indigenous Self-Determination, New Urban Reserves, and the Neoliberalization of Colonialism,” Antipode 49, no. 4 (2017): 928–945. ↩

In The Scale of a Plantation

Robin Honggare

Photographing plantations is a matter of scale. One can depict a plantation field from high above, shrinking its vastness into a congruous part of the horizon, but one can also depict it from walking on the ground, letting the endless rows of individual plants dominate the frame. Scale, in this genre, determines which reality is included, which is omitted, and how the subject should be perceived.

The style of plantation photographs has evolved over time. Nevertheless, early examples from the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), taken from the mid-1880s to early 1900s, are a curious case. In landscape paintings of the region, productive land was for the most part absent, despite being the primary concern of colonial agriculturalists and administrators. This absence, however, as argued by Susie Protschky in Images of the Tropics: Environment and Visual Culture in Colonial Indonesia (Brill, 2011), was counterbalanced by the presence of plantation estates in the photographic format. As commercial photography studios flourished in the nineteenth century, photographers began to capture plantation fields and processing factories. They produced images either as part of company reports and documentation procured by plantation estates or as souvenirs to be purchased by the wider public.

Woodbury & Page, a commercial photography studio established by Walter Bentley Woodbury (1834–1885) and James Page (1833–1865), was among the first to capture the reality of extractive industry in the Dutch East Indies. The studio often advertised its services through local newspapers, such as Java Bode, in which on 18 October 1879 it published a list of more than six-hundred photographs available for purchase. The images comprised a great variety of, among others, iconic buildings, residences, public infrastructure, and scenic landscapes, stretching from Aceh to Kupang. This list suggests that plantation photographs were already among the extensive collectible visuals sold by the studio.

As far as scale is considered, we can see a specific gesture, one which further complicates Protschky’s observation about the images of plantations, in an album authored by Woodbury & Page. The studio mainly captured the plantations from far away and high above, just like how colonial painters produced scenic representations of the Dutch East Indies (a genre known as Mooi Indië) by romanticizing its natural and beautiful territory without really capturing its exploitation. Though plantation grids were produced through continuous labour, Woodbury & Page photographs treated them as picturesque landscapes, fit into the camera frame and presented as integral parts of their natural surroundings. Scale plays an role in these images insofar as it makes the labourers responsible for cultivating the plantations invisible or visually insignificant.

The visualization of plantations in this early commercial photography was thus more derived from the aesthetics of landscape painting than it was influenced by a documentary perspective. In comparison, later photographers, such as Charles (born Carl) J. Kleingrothe (1864–1925), provided a relatively more holistic picture of plantations by zooming into production processes, including into the interiors of processing facilities in which labourers became an indispensable component of the assembly line. This shift in scale was likely connected to the desires of clients. Woodbury & Page treated their images more as souvenirs to be purchased by the general public, whereas Kleingrothe captured the plantations more closely as he was commissioned to do so by plantation companies.

In The Scale of an Artificial Pond

Émélie Desrochers-Turgeon

When Arthur Erickson showed Cornelia Hahn Oberlander a sketch of the University of British Columbia Museum of Anthropology (MOA), she suggested to “simulate the landscape of Haida Gwaii with rolling hills, native grasses, and an ethnobotanical walk through the woods.”1 Located on the unceded territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) First Nation, the MOA is, in fact, one-hundred kilometres south of Haida Gwaii island. Lacking funds to visit the island, Oberlander relied on a magnifying glass to identify vegetation in the book This is Haida2—she eventually specified maples, hemlocks, cedar, ferns, and mahonia, to name a few, to extend the museum’s interpretation of Indigenous cultures into the landscape.

Perched on a cliff overlooking the North Shore mountains and the Georgia Strait, the MOA sits within a terrain that is vulnerable to erosion and dotted with World War II gun emplacements.3 To site the building, Erikson and Oberlander used 1:500 scale models that included topography, trees, parking, adjacent buildings, and roads.4 The MOA’s oversized precast concrete columns and beams echo the scale of local trees such as the Western red cedar, the Douglas fir, or the Sitka spruce. Architecture critic John Clifford noted that the museum gives “justice to the monumental aspects of Northwest Cost carving and spatial design.”5 A reflecting pool facing the Great Hall amplifies this monumentality, while the pool’s curved form framed by a shell and pebble beach seem to naturalize its presence on a contested site.

-

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, “Museum of Anthropology Celebration of the Pond,” 9 September 2010. AP075.S1.2004.PR02.024, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander fonds, CCA. ↩

-

Anthony Lawrence Carter, This is Haida (Vancouver: self published, 1968). Oberlander also read Erna Gunther’s 1945 book Ethnobotany of Western Washington: The Knowledge and Use of Indigenous Plants by Native American. Susan Herrington, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, Making the Modern Landscape (Charlottesville; London: University of Virginia Press, 2013), 158. ↩

-

While the museum was built around the gun emplacements, one gun emplacement was used as a foundation for Bill Reid’s sculpture Raven and the First Men. Herrington, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, 160. ↩

-

Herrington, 158. ↩

-

James Clifford, “Four Northwest Coast Museums,” in Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, eds. Iva Karp and Steven D. Lavine (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991), 218. ↩

Thirty kilometres east of the MOA is the Simon Fraser University campus, also designed by Erickson, in collaboration with Geoffrey Massey, in 1963. The campus is a linear megastructure, sitting atop Burnaby Mountain like an acropolis. It was built by cutting terraces into the hillsides, emphasizing the contours of the topography and horizontally integrating the building into the landform. The campus core is the Academic Quadrangle, inspired by Al-Azhar University’s courtyard in Cairo.1 Its focal point is an artificial pond that reflects the surrounding concrete brise-soleils, the sky, and the mountains, while providing a popular public space, a skating rink, and a habitat for hundreds of koi fish.2 Sitting on a concrete footing in the reflecting pond is also the foundation stone, a tribute to Simon Fraser, a Scottish explorer working with the Northwest company and one of the first colonists in British Columbia.3

-

David Stouck, Arthur Erickson: An Architect’s Life (Maidera Park, BC: Douglas and McIntyre, 2013), 183. ↩

-

“50 little-known facts about 50-year-old Simon Fraser University,” The Province, 30 January 2016, https://theprovince.com/news/local-news/50-little-known-facts-about-50-year-old-simon-fraser-university. When the pond was cleaned in 2008, four-hundred fish were temporally relocated to a tank, while glasses, hockey pucks, a hearing aid, a diary, cellphones, a bowling ball, liquor bottles, and a book were also dredged up. ↩

-

Nicole Magas, “The Reflecting Pond Boulder: A Monument to Failure,” The Peak, 24 May 2019, https://the-peak.ca/2019/05/the-reflecting-pond-boulder-a-monument-to-failure/; “50 little-known facts about 50-year-old Simon Fraser University.” In 1968, a student group pressured SFU to rename the school “Louis Riel University,” arguing that Simon Fraser was “a member of the vanguard of pirates, thieves and carpet-baggers which dispossessed and usurped the native Indians of Canada from their rightful heritage.” ↩

The reflecting ponds at the Museum of Anthropology and Simon Fraser University are natural elements inserted into a brutalist design. While they may have been designed to convey harmony, they can be read as manifestations of a desire to master and extend control over settled terrains and waters. Here, the scale of the artificial pond both reflects and disrupts the long-standing power dynamics of settler colonial relations. In its murkiness, its shallowness, and its entanglement of biological and mineral matter, the artificial pond intensifies local relational material practices while magnifying them far beyond the boundary of a building.