Futurecasting: Towards Indigenous-Led Architecture

Nicole Luke speaks to Rafico Ruiz and Ella den Elzen about collaboration, collectivity, and listening in the future of Indigenous design

ᐊᖏᕐᕋᒧᑦ / Ruovttu Guvlui / Towards Home was co-curated by Joar Nango, Taqralik Partridge, Jocelyn Piirainen, and Rafico Ruiz, with Ella den Elzen as Curatorial Assistant. We have also published talks with designer Tiffany Shaw and artists Carola Grahn and Geronimo Inutiq.

- RR

- What does the title that we have given to this project—angirramut, ruovttu guvlui, or Towards Home—mean to you?

- NL

- Towards Home is a really suitable name for the project. I think it’s something that everyone can relate to, because everyone’s concept of what home means is an individual experience. It is also a strong insight into northern Arctic Indigenous architecture and gives a good understanding of that culture and lifestyle, and yet it is still relatable. Everyone needs a home, everyone wants a home, so I think this idea of a safe space where people get to really show their characteristics and culture is key.

- RR

- I think it’s something underexplored or maybe not highlighted enough. To create a safe space for different community members from the Arctic is an important ambition of the project. And with the title, there is this idea of movement towards something that maybe isn’t here in the present, but is more in the future. We tried to encapsulate this with the three guiding questions we’ve been working with: where is home, where do we go from here, and where does land begin? How do you perceive this movement towards something?

- NL

- I think everyone is curious about the future, but in going towards something it’s also important to look back and acknowledge how you got to where you are. I think that this idea of process is important, and it’s something we’ve been trying to highlight with the Futurecasting program by gathering Indigenous designers and duojárs to participate in various seminars and a design workshop in Sámi territory, in Kautokeino, Norway. Even though we didn’t have an exact idea of what the work coming out of Futurecasting would be when developing its structure, the program is really about everyone’s individual experience and ideas. It’s about process over project and showing how all the participant’s processes are different and experience-based.

- EdE

- What have you learned through this process of prioritizing conversation and collectivity as a method during the Futurecasting project?

- NL

- I’ve been learning that listening is important because everyone has different directions and ideas that relate to Towards Home. I think it only adds to everyone’s work and everyone’s motivation, and it makes more of a community effort towards Indigenous architecture and sovereignty. That’s always been something that I’ve been seeing out of this process.

- EdE

- I am curious to hear your thoughts about the future of design in the Arctic and in northern regions, through an Indigenous-led approach, because the North has historically been considered this tabula rasa or this blank space that can just be freely designed upon by southern non-Indigenous architects. How would you like to see Indigenous architects in particular leading the conversation around design in Northern communities?

- NL

- I think it’s still going to take more time. There is always some lag, and we can see it with the lack of Inuit architects and even Indigenous architects in general. I think it’s important for these types of conversations to happen in order to start or assist in that development. For the future, I hope to see architecture continue to develop in the Arctic and in a way that is strategic.

For example, I hate the idea of suburbs in the Arctic. They don’t make any sense. I recognize there are housing issues and buildings need to be built fairly quickly, but we need to think more broadly than just about housing being built: It’s about having specialized workers who will have to be sent up North, alongside thinking about sustainable forms of eco-tourism. It’s about having this economy of different things that benefit the community that are more than just a building. I think that whole process could be important because not only are you bringing people in to work on these building projects, but they’re learning more and so they’re more obligated to create a special project that they care about. I just like to imagine that people coming into the community are not only taken care of, but they also want to take care of the community beyond the project. Because when you care about a project, and you care about people and relationships you develop, the whole end goal benefits from it. - EdE

- What does a more compassionate form or way of designing look like?

- NL

- I think the design process needs to be more strategic. I think budget and timeline are both important factors. You need them in some projects to answer questions and move forward, but I think there should be a more deliberate way of building that considers more than just the budget. For instance, when designing housing, can there be a community space built in? Can it be more than just a single space? Maybe there’s workshop space involved, and the programming is more flexible. Having those conversations with people in different communities would be helpful during the design process, and I think that’s all based on relationship building and commitment to the project.

- EdE

- Speaking of relationship building, how or what forms of knowledge can be shared across North/South Indigenous communities across Turtle Island, Inuit Nunangat, and Sápmi?

- NL

- I can’t really say exactly what forms, but I’ve seen how there is a transition of way of life from Nunavut to Manitoba, so there is a knowledge transfer between the two that is community-based. Because I lived in Winnipeg for most of my life, I always wanted to go up North. Growing up, I have always been able to visit and stay with my sister or my family in Kivalliq, but I have always thought it would have been neat to go somewhere else outside of Nunavut. Even if it was Northwest Territories or Yukon, it would be great if there was some sort of exchange program between the North and the South that would allow you to get to know and learn from different communities. Or in the architectural context, if you’re working on a project maybe there’s a place where you can stay for a couple of weeks to start developing the project rather than just having a quick two-day fly-in to a community and then you’re out. I think that is pretty unfortunate, because sometimes you are supposed to be building for the community and yet you must figure everything out in eight hours or less. There should be a better process than that.

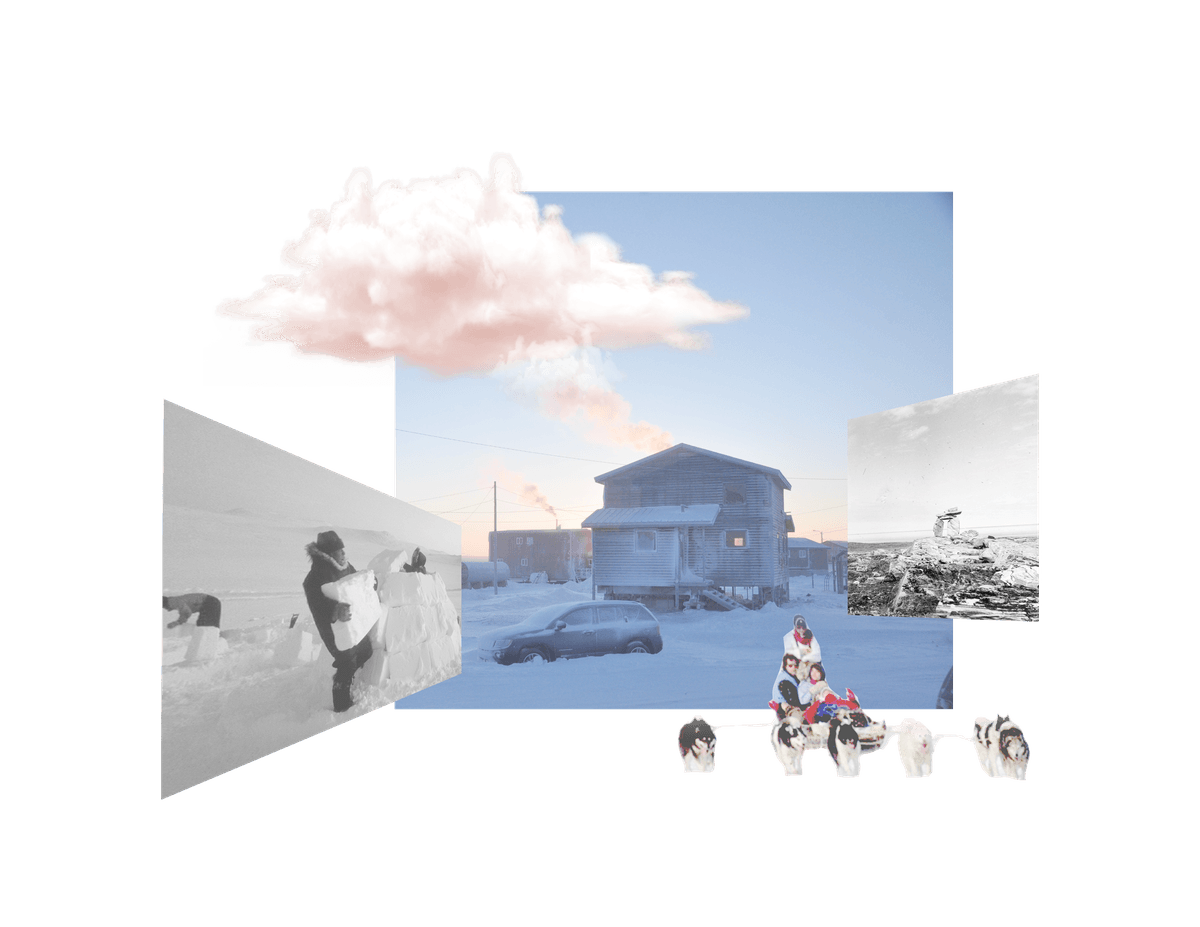

ᐊᖏᕐᕋᒧᑦ / Ruovttu Guvlui / Towards Home, installation view of the Futurecasting Gallery, which shows the work of nine emerging Indigenous designers, architecture practitioners, and duojárs from across Turtle Island and Sápmi. Photograph by Mathieu Gagnon © CCA

- EdE

- It’s interesting what you’re saying about these relationships within and across different provinces and territories and this idea of knowledge exchange, even within what is now known as Canada. It’s important to acknowledge all these diverse cultural differences across the North and South, and in individual communities that require a stronger depth of community engagement. With Futurecasting, the project is suggesting that cold climate design needs to be understood beyond colonial or geopolitical borders, and there is a kind of exchange or knowledge sharing that is happening between the Indigenous participants from Canada and the Sámi participants. How did you understand that kind of framing?

- NL

- I’m not sure I fully understood what would happen over the course of the project. I’ve always been interested in international, circumpolar, Indigenous architecture or peoples and I think that there’s a lot of benefit to discussing with people beyond colonial borders and that is broader than this idea of policy. Each country has different policies, different goals for what they want for their infrastructure, and maybe one country is really benefiting from one type of policy while another is not. Learning from each other is important, and meeting more people is useful and significant to collaborating beyond your own community.

- EdE

- How do you want to incorporate traditional knowledge and craft techniques, or the knowledge of elders or knowledge-keepers, into a contemporary design process?

- NL

- I like to also consider myself a craftsperson. In terms of architecture, even just starting small to build big helps to figure out certain spaces and meanings of a building or a project. I don’t think this process should be lost. Right now, I would describe architecture as being designed in an international style. Everything is steel and glass and it’s pretty industrialized in a lot of places, regardless of where you find yourself in the world. I don’t think that works everywhere, especially in the Arctic where architecture is still being developed. Even infrastructure itself is still trying to grasp how to maintain existing communities. To develop architecture in the North that just looks the same as in the South doesn’t make sense. Having traditional techniques embedded in the process helps community members revitalize their language. For example, when you build, let’s say, an igloo or even a teepee… there are certain words for each structural member that have different meanings and that have different teachings attached to them. Building then becomes a teaching tool.

- EdE

- With that in mind, what does it mean to design on Indigenous land?

- NL

- I think that stating and acknowledging the Indigenous land you are designing on is a powerful gesture, because you’re automatically acknowledging the traditional cultures there. I think it helps to understand what the meaning of the project is, what the meaning of the relationships are that you wish to build; and you feel the need to do better. I think what it means to design on Indigenous land is to do your homework, to pay respect to the communities you’re engaging with, and to listen and apply what you learned.

- RR

- I wonder if you might reflect on the possibilities of design education, maybe specifically in Inuit Nunangat, in Nunavut. What sort of potential is there for the future?

- NL

- I hope there’s a lot of potential. There definitely needs to be potential, because if you talk about design education, I think you have to talk about general education first. I realized this right at the end of high school because I was working for Manitoba Inuit Association collecting a database of scholarships for urban Inuit in Manitoba. I realized that the high school graduation GPA [Grade Point Average] and the subjects that students are learning in Nunavut are not comparable to those in Manitoba. If somebody graduates in Nunavut and they want to study at university in the South, there’s a huge jump already for them to not just apply, but to have the GPA and know the required subjects.

On top of that, there’s the increased inaccessibility of design education: if people want to go into architecture or anything in the arts, it’s difficult. There are just way too many hoops to jump through to begin with. I think the idea of design education needs to be something that is introduced at a younger age and that people are exposed to for a bit longer. I went through an environmental design program and there are so many types of jobs that you can get with just that degree, which I think is really great.

In grade school or high school, it would be important to do even more workshops and just discuss the possibilities with students. I think there needs to be better buildings up North, because being in the South I’ve had the chance to learn in some pretty great buildings. When you’re in a space that you really enjoy, it makes you enjoy what you’re doing in there and it really fosters your actions and what you want to. Of course, I don’t want to say every building in the North is bad, but I think that there is a lot of misunderstanding of what a building should be in the North. I think fostering a good space for that education is also very important.