Flirting With Fulfilment

Samir Bantal interviewed by Jack Self on the consumer's search for meaning in contemporary retail environments

- JS

- Global capitalism is founded on consumerism. It’s so central to everything that we do. Given that, how do you think we should understand retail? As a civilization? A culture?

- SB

- I think consumerism has always been part of human civilization and has even enabled the development of civilization and culture. I would also say that culture has always flirted with consumerism, and maybe consumerism is also a cultural form. But now we’re trying to find meaning in retail and in consumerism. Retail traditionally has been thought of as an experience, and I think that’s fading away as it becomes more about meaning and community.

- JS

- How do you understand meaning-making?

- SB

- The cornerstones of society have dramatically changed. For example, something that was as central as religion has almost been replaced by other beliefs. But we’re constantly trying to find meaning, understand meaning, or define meaning, in our daily lives. And consumerism is only one way in which we explore that.

- JS

- Virgil Abloh famously said that the first slide you sent him for the Off-White Miami retail project asked, “Is shopping relevant?” So, is shopping relevant?

- SB

- This is a question that architects involved in retail projects are constantly trying to answer. Shopping has always been intertwined with modern life, dating back to when we first started trading goods for goods and, later, goods for currency. Shopping is now a catalyst for a kind of fast culture. And in today’s digital altar society, I think it will become even more relevant than we think. What Virgil and I discussed in the early phases of the project was that I looked at him as not only a fashion designer or an architect but as a cultural phenomenon. The Off-White Miami project was conceived as a gathering place that could respond to the cultural rhythm of the city, rather than function as just another place to sell products. To say “let’s do a store” felt irrelevant or restrictive, in a way, because it would leave out all the alter egos that Virgil manifested. I thought it would be more interesting to see if the stores would be able to change and transform into a popular cultural event. Colette, the store in Paris, used to have this kind of attraction to youth culture both in France and beyond. It connected influential people from the US and Asia and brought them together, within this market of ideas.

- JS

- You were talking about the speed of culture and trying to anticipate speed in design. Should architecture try to keep up with the acceleration of culture?

- SB

- Architecture moves slowly, whereas the life cycle of shopping changes quite fast. Ten years ago, a concept could last for five years. Now it’s not able to keep up with the pace of changes in popular culture. You can see the shift within fashion, where you used to have fixed moments of presentation—the fashion shows—and communication with consumers, and now we can see how Virgil used social media as a continuous form of broadcasting and not just a way to sell goods. Architecture can learn something from these different methods of communication. But for the Off-White store in Miami, Virgil and I discussed that it was more interesting to design a loft space, a kind of Amazon fulfilment centre where the interior changes according to the season and shifting needs. Culture can literally move in, and the front façade would be pushed back, and the street would slowly move into the store. We’re looking at something that is more defined by instability than by stability. Culture is unstable.

- JS

- You mention the idea of a fulfilment centre. What does it mean to be fulfilled?

- SB

- I looked up the definition of fulfilment when we were working on the project, and it was defined as the achievement of something desired, promised, or predicted. We’re living in an interesting time and basically all three elements of fulfilment—the desired, the promised, and the predicted—are out of our control, because our intended footprint or dream world is echoed to us through social media. And this mechanism is faster in predicting and telling us what we want before we even know it. The idea of fulfilment, through which you project these ideas and desires, in a way turns around and tells you what those ideas and desires look like.

- JS

- I’d like to ask you about trends changing faster and faster. The 1980s were “in” when I was in my 20s, and I think that whatever moment you’re in now, trends bring back what happened twenty or twenty-five years earlier. Perhaps it’s because people who are in their mid-40s are now in positions of power and they’re like, “You know what was cool? Me in my 20s.” But the 1980s comeback in the early 2000s was filtered through a lens of French techno, and layers of interpretation went into it, which made it a kind of pastiche of the 1980s. Whereas when I look at teenagers now dressing in the style of the early 2000s, it’s clear that they can go and look at images on the Internet of what Christina Aguilera was wearing in 2002. And they perfectly recreate it. It’s like there’s no interpretation that goes on at all. There seems to be less interpretation and more appropriation. The right thing appearing at the right time in the right context is somehow more important than its novelty. So, I wonder if the future of shopping needs to be new at all?

- SB

- I think that the consumer’s search for meaning is more of a driver than newness. When we started our research on the countryside a couple of years ago at AMO, we contacted the AI division of Google because in our opinion they would be able to predict how the world would evolve.

In that conversation, they stated that gender, which we always considered to be binary, is now actually vectorial. And you see this kind of fluidity in brands, which are a representation of this search for meaning. Why would I stick to one kind of principle, brand, or product, if I can put it together myself?

- SB

- I applied this new logic in a project where we were looking at the future of housing. In the 1950s, it was very clear for whom housing was made: the prototype of a nuclear family composed of father, mother, and two kids—ideally a boy and a girl. These were the prototypical consumers, almost their ideal pictures. Fast forward to now and this consumer is much more like an Isa Genzken artwork, where you see all these figures and you can’t really define their gender or age.

The search for meaning today is a pastiche, a collage of different desires. And sometimes these desires can be contrary to each other, but that seems to be okay. Younger generations could probably claim that there is meaning to something like sustainability in a consumerist society. - JS

- The idea of a retail apocalypse points to its irrelevance. When retail goes extinct, what should architects do next?

- SB

- Well, the first part of this question is whether retail will go extinct. I think it might in its traditional form, but what we’ve learned from the past two and a half years, during the pandemic, is that online retail increased and became something that people became accustomed to very quickly. Conducting this interview via video conference is something that we would have hesitated to do three years ago. Now it’s perfectly normal.

I don’t think retail will go extinct, but it will evolve into something different, where the boundaries of retail get much more blurred. And I think we’re already seeing how it infiltrates into art, science, and other domains like the gaming industry. There’s a complete digital ecosystem outside of our physical idea of retail.

I think that retail will subtly infiltrate domains where it is already embedded. But the physical representation of a store where you have a door, you walk in, there’s a counter, and you order something—yes, that form of retail could perhaps go extinct. Although retail can reverse or return to these ideas in new ways. When Amazon started, you would have never expected it to invest in offline, physical spaces. And that’s happening increasingly and on a large scale.

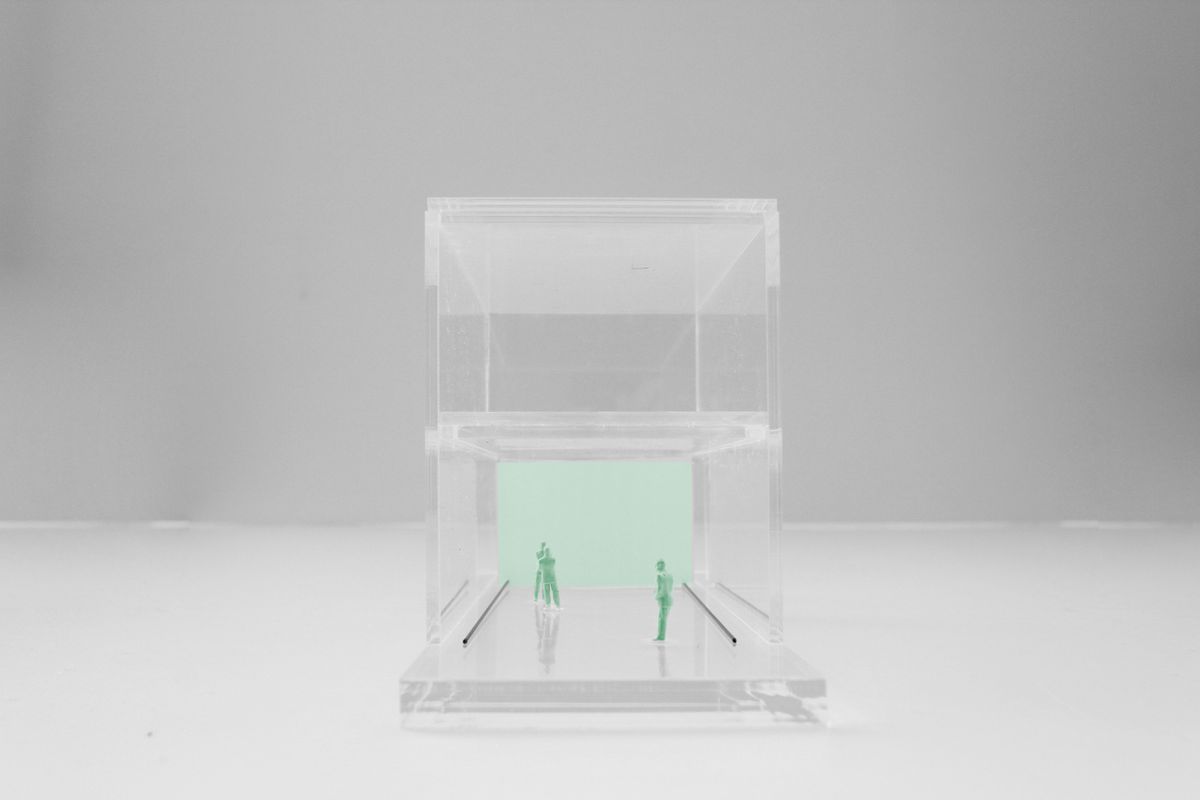

Retail Apocalypse is curated by Fred Fischli and Niels Olsen. The exhibition is currently on view in the Hall Cases and Octagonal gallery and runs until 15 January 2023.