Carbon Present

Arièle Dionne-Krosnick

This text introduces a virtual exhibition by participants in the 2022 Toolkit for Today: Carbon Present seminar, which selects and rereads objects from the CCA collection according to various themes related to how carbon shapes our present built environment and ways of being.

The current climate crisis is the inescapable conclusion of humanity’s rampant exploitation of the world’s resources for its benefit. As we know from Vaclav Smil, the production of indispensable materials of modern living including cement, steel, plastics and ammonia, which depends heavily on the combustion of fossil fuels, releases an inordinate amount of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, warming the world at an accelerated and unprecedented pace.1 Intertwined systems of power and domination from colonialism, racial capitalism, patriarchy, and the military-industrial complex, among others, have normalized the exploitation of people, land, and resources as righteous, and the accumulation of power and wealth as worthy of all excesses.

Global leaders meet annually to define the “ambition and responsibilities” of countries to climate change; the 2023 COP28 agreement acknowledged the need to transition away from fossil fuels for the first time. This admission of the ongoing harms of coal, oil, and natural gas extraction comes on the heels of decades of mobilization by scientists, activists, and citizens clamouring for lasting change, real accountability, and radical alternatives to energy production.

Yet, as a recent Amnesty International report on COP28 has argued, “loopholes allowing fossil fuel producers and states to continue with business as usual” denote a global lack of willpower to hold powerful corporations and oil-producing states accountable for reaching imperative emission goals.2 Carbon capture and storage and other experimental technologies like direct air capture or chemical looping end up benefitting the oil and fossil fuel industries by making them eligible for substantial tax-breaks. These technologies also support enhanced oil recovery (EOR), which increases production in the long term rather than addressing an urgent call for change.

Existing building and construction industries are responsible for around 40 percent of the world’s carbon emissions. Prevailing solutions to tackle architecture’s carbon problem tend to privilege new constructions and materials slapped with eco-labels like “Built Green,” “LEED Certified,” or “Carbon Neutral,” which often amount to little more than marketing tactics. These techno- and human-centred resolutions are insufficient to tackle the global climate emergency.

-

Vaclav Smil, How the World Really Works: The Science Behind How We Got Here and Where We’re Going (New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2022). ↩

-

“COP28 Agreement to Move Away from Fossil Fuels Sets Precedent but Falls Short of Safeguarding Human Rights,” Amnesty International, December 13, 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/12/global-cop28-agreement-to-move-away-from-fossil-fuels-sets-precedent-but-falls-short-of-safeguarding-human-rights/. ↩

What does climate accountability and responsibility look like for architecture and design? How do we, following Simone Ferracina’s provocation, “begin to forswear our contributions to ecocide, and decouple design potentials from ecologies of extraction, exploitation, obsolescence—and from the imperative of economic growth”?1 For historians and other scholars of the built environment, it has become imperative to reconsider our objects of study in terms of their reflections or impacts on the climate, as well as to trace the connections between accepted histories of architecture, culture, politics, and sustainability. This commitment compels a more explicit reading of the historic and ongoing complicity of architecture in the climate crisis. Such a reading of architecture produces what Bertolt Brecht termed Verfremdungseffekt, a distancing effect that better equips researchers and publics to critique and analyze their biases and behaviours toward built and natural environments.

Spanning centuries, geographies, and scales, the 2022 Toolkit for Today project is an invitation to acknowledge the “carbon present”: the invisible yet pervasive role of carbon in shaping our world and experiences of it. The 2022 researchers have put on their “carbon lenses” to revisit objects from the CCA Collection with the aim of building and revising interpretations, histories, and legacies of architecture’s relationship to climate. Each collection of objects considers a unique aspect of our carbon present: Combusting, Transforming, Exploiting, Regulating, and Easing.

-

Simone Ferracina, Ecologies of Inception: Design Potentials on a Warming Planet (London: Routledge, 2022), 2 ↩

Combusting

Hamish Lonergan, Iva Resetar, Demetra Vogiatzaki

Combustion is a process in which a substance, typically a fuel, reacts with oxygen to release energy in the form of heat and light–think of it as a controlled, transformative dance between fuel and air. In simple terms, when you strike a match or ignite a gas stove, you’re witnessing combustion in action. This chemical reaction not only powers everyday activities like cooking and heating but also drives car engines and generates electricity in power plants.

While essential for powering the modern world, combustion exacts a heavy toll on the environment. The burning of fossil fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas releases vast amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere, contributing significantly to the greenhouse effect and climate change. At the same time, the extraction and combustion of fossil fuels often result in habitat destruction and environmental degradation.

The objects from the CCA collection presented in this series trace the historical development of these contradictory dynamics of combustion. They chart an arc of responses to combustion as it relates to the experiences and design of the built environment: from fear to enthusiasm and back to crisis. By analyzing archival documents and governmental regulations, we note how, before the eighteenth century, combustion was considered a leading threat to buildings and cities, even as it provided the means to heat them; architects and craftspeople often responded to risks of fire with cautious and deliberate material and construction choices.

As you navigate through this series of objects, we invite you to keep in mind the double meaning of combustion as power: though it provides energy, its production is tied to those who control resources, processes, and knowledge.

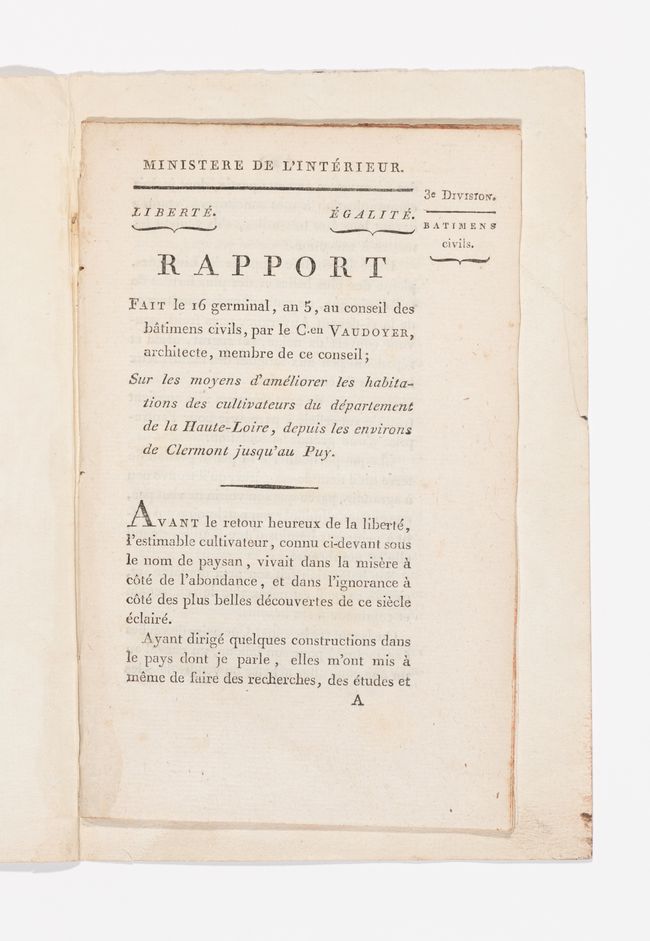

Antoine Vaudoyer, Rapport fait le 16 germinal, an 5, au Conseil des bâtimens civils / par le c.en Vaudoyer…sur les moyens d’améliorer les habitations des cultivateurs du département de la Haute-Loire, depuis les environs de Clermont jusqu’au Puy (Riom: De l’Imprimerie de J.-C. Salles, 1797). PO9821 CCA.

Tuff is a zeolite byproduct of volcanic eruptions that has been recently deployed as a sustainable agent in carbon dioxide capture. Tuff has also been used for centuries as a construction material, especially in infrastructural works, due to its durability and lightness. In this study from the late eighteenth century, the French architect and state agent Antoine Vaudoyer (1756–1846), foregrounds tuff as a central element for the improvement of living conditions in impoverished or agrarian regions with volcanic terrain. Vaudoyer praises the qualities of this material—its lightness, porosity, convenient sizing, and agreeable appearance—further highlighting the benefits of using local materials for new construction.

Société royale d’agriculture, “Constructions économiques pour les campagnes ou bâtiments incombustibles. Rapport des Commissaires de la société royale d’agriculture, 21 Juin 1790,” in French Architecture: Letters and documents, 1776–1819. PO11694 CCA.

Rammed earth (pisé) construction is continuously gaining popularity due to its environmental benefits, including the low greenhouse emissions of the process, as well as the thermal efficiency of the product. François Cointeraux (1740–1830) was one of the first architects to advocate for its use, passionately advertising his discoveries in a plethora of pamphlets, letters to the French government, and competition entries (some also featured in this archival folder). In this review of Cointereaux’s proposals, the agents of the French Royal Society of Agriculture outline the numerous benefits of building with pisé, focusing particularly on its incombustibility—a property that they thought might solve the enduring problem of fires in the countryside.

With the advent of industrialization and the invention of air conditioning systems, combustion evolved from an everyday aspect of construction to a highly technical scientific domain. Yet this illusion of human control over temperature would not last long. The late twentieth century witnessed the dawning realization that the combustion of fossil fuels was heating the Earth’s atmosphere at alarming and unsustainable rates, often prompting a return to those same craft-based construction processes and technologies that had been eclipsed earlier in the century.

Ernest Cormier, Thermometer. ARCH252051 Ernest Cormier fonds, CCA

Temperature is the first marker of heat and carbon accumulation. Having left the “well-tempered” environment of the Holocene, heat has become a measure of a “displaced, fluctuant, chaotic” state, possessing “a new literality, which disturbs the metaphorical uses we make of it”, as stated by Steven Connor.1 Since observations of greenhouse gas emissions began with the “Great Acceleration” of the 1950s, evidence has mounted regarding how CO2 and other trace gases generated by fossil fuel combustion trap heat in the Earth’s atmosphere, driving changes in climate and increases in temperature on a planetary scale.2 In the bound space of our planet, heat cuts across varying scales of particles, environments, and bodies. Buildings, even when kept conspicuously cool, are permeated by heat. A thermometer from the Ernest Cormier fonds is an everyday instrument to diagnose artificial temperature control in built environments and our contemporary resistance to personal discomfort.

“A Silk Mill Installation and Psychometric Chart” in Carrier air washers and humidifiers, with notes on humidity (Buffalo, NY: Carrier Air Conditioning Co., 1908), 32-33. ID:90-B6245 CCA

Industrial environments such as textile mills were the first testing grounds for new thermal regimes. As air conditioning technology became more widely accepted and implemented, its focus shifted: applied knowledge of thermodynamics intertwined with that of human perception, introducing a set of tools for creating, observing and evaluating the indoor climate and its effects. This technical language, such as Carrier Air Conditioning Co.’s Psychometric Chart, superimposed quantitative methods derived from meteorology on a scale to manage humans’ comfort range. Later, equations for calculating thermal comfort abstracted comfort into the universal notion of “optimum” satisfaction. Beyond the promise of creating a stable, controlled indoor environment, air conditioning outgrew its beginnings in the factory to become a comprehensive socio-technological project.

These selected objects also remind us that the history of combustion is not only utilitarian; it also intertwines with interests in art, beauty, and marvel. Pyrotechnics and the use of fire as a spectacle date back centuries, with cultures worldwide employing fireworks and controlled fire displays for celebrations. This historical link between fire and spectacle serves as a bridge to contemporary design and the ongoing transformation of environmental awareness into a performative and sometimes falsely optimistic act.

Melvin Charney, Malevich altered (Malevich redrawn), 1978. Coloured pencil on a photocopy on wove paper. DR1984:1572 Melvin Charney fonds, CCA. Gift of Melvin Charney

In his study for Front Page Construction…No. 4 (1979) in the collection of the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec, Melvin Charney overlays motifs from Constructivist and De Stijl architecture onto a photograph published in the business section of the New York Times from 20 February 1975. Here, the chairman of United Steel stands over a model of a new mill near Gary, Indiana, as blue and red planes shoot across the page. The study forms part of a series like the one in the CCA collection that reworked newspaper pages to highlight the visual relationships between buildings and calamitous events. Drawing on Michael Polanyi’s notion of “tacit knowledge,” Charney understood these relationships as evidence of a material reality embedded in buildings and cities that could be intuited by assembling visual, rather than written, sources. One of these repetitions, as Charney writes in his commentary on a similar work, is the trope of men in power pointing at architecture models, their gesture figuring a shorthand for the flows of capital that move through construction and cause harm to vulnerable people. But from the vantage of today’s climate crisis, another implicit reality might be clearer to us than it was to Charney: the importance of carbon in matters tying architecture and industry. The lingering effects of the 1973 oil crisis suffuses the text of an article on declining automobile and tire sales in another of Charney’s collage interventions. Framed by two streaks of blue, “Kuwait” stands out in a headline, underscoring the way carbon and oil entangled domestic US production with oil producers in the Middle East. The steel industry, we read, had “withstood the recession relatively well so far”, but we know this carbon-intensive industry would later be devastated following the oil crisis in the wake of the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

Hubert Rohault de Fleury, Nocturnal elevation of an unidentified domed building surrounded by a colonnade, perhaps a cenotaph dedicated to Newton (1800–1812). Pen and black ink with brown and black wash on laid paper. DR1974:0002:012:014 CCA. © CCA

We do not know much about the authorship or purpose of this anonymous drawing. It is part of a folio containing student drawings by the architect Hubert Rohault de Fleury executed at the École spéciale de peinture, sculpture, et architecture in Paris (1800–1802). The austere geometry of the forms and the emotional qualities of the scene evoke Étienne-Louis Boullée’s enduring influence on Enlightenment architectural pedagogy. In the late eighteenth century, draftsmen frequently depicted fire to highlight and animate the aesthetic perception of buildings. As in this image, flames were skillfully used to illuminate and bring to life monumental structures. This captivating graphic interplay of light and shadow—drawing inspiration from Enlightenment principles, Freemasonry symbolism, and contemporary scientific advancement—accentuated the affective and symbolic qualities of architectural design. In the present day, such a nexus between combustion, architecture, and spectacle has taken on a new dimension. The environmental performativity of buildings has evolved into a contemporary spectacle, in which sustainability regulations and narratives command the spotlight. More and more, architectural forms theatricalize eco-friendly concepts and materials, transforming the design process into a visual representation of environmental consciousness.