Topology and Tracing Paper

Fala Atelier on the Umberto Riva fonds

We were not so familiar with the work of Umberto Riva. At best, we could say that we appreciated the plans of Casa Miggiano, with its mysterious three-dimensional Kelly-esque cut out, and fetishized the fireplace of Casa Insinga. He was to us, as we understand he is to most, one of those illustrious Italian names that float in the architecture cosmos, where they eventually become mixed up with each other.

The invitation to take part in a “Find & Tell” on Riva’s archive at the CCA, therefore came as a surprise. Firstly, due to our announced ignorance towards the architect in question; and secondly, due to our discernable inexperience in any sort of previous archival work. Maybe our experience as “practitioners,” or the comparable scale of our built work, could point to some reason why we were considered.

A few moments of his work captivated our attention. While we had seen them before, the mysterious and heavy Case di Palma and the light and beautiful pergola of Casa Frea, restored what we thought were lost memories. As such, prior to flying to Montréal, we tried to find more information, to study and hopefully (even if superficially) understand Riva, to be able to put him on a map, to place him in our bookshelf in the atelier.

While diving into the valuable, preliminary materials made available to us by the CCA, a theme almost instantaneously materialized: form. Not form in the volumetric or edifice sense, form as a negotiation of lines within his drawings. Form as an end in itself, not as a means to an end; form as architecture, regardless of its scale or medium. The tension between the orthogonal banality of his rooms and the geometric freedom of his elements led us to wonder: within his formal expressionism, was there something that we could discover? Could we build an argument around the idea of the drawing as an autonomous entity within the project? (Which also happens to be a recurring obsession of ours.)

In an interview conducted by Hans Ulrich Obrist for Pin-Up in 2019, Riva stated that he found “points in common between his plans and his paintings” and explained that “his plans showed a certain degree of formal autonomy as a visual product”. Perhaps flimsy as a starting point, we assumed this could be our entry to Riva’s universe and a first draft of an idea emerged: finding a not circumstantial relation between his drawing’s autonomy and the autonomy of the drawings by names we had studied for the last decade and whose archives were stored at the CCA—Yoh’s, Eisenman’s, Siza’s—specifically looking at a limited time period between the late 70’s and the early 80’s. By framing Riva amongst authors who we were actually familiar with, within a theme we had studied before, in a limited period we come to comprehend, and towards which we could establish the argument, maybe Riva would allow for a grounded speculation, reducing our original distance to his work.

Pause. Crossing the Atlantic

Our first impression of the CCA was of an odd and efficient clock. Regardless of a certain imaginary we carried from afar, the logical procedures and the hygienic archives provided significance to what we see now as a concrete reality of what an archive truly is behind the curtains. Inside the endless folders and boxes, architecture in its purest and uncompromising form: the thing per se, beyond gravity or the ordinariness of daily life. A formidable technical and human team makes the machine run. As it seems, in line with best conservation practices, we should not wear white cotton gloves while going through tracing paper documents, since we would lose the sensibility of our fingers.

Our selection happened after a first, more general and comprehensive curation, which resulted in the Rooms You May Have Missed exhibition at the CCA in 2014. Riva’s most recognizable and representative drawings within the CCA collection had already been scanned and made available to the public. As such, our mission was not to make sense of Riva as a whole, but to make sense of a fragment, a layer within layers.

Over four consecutive days, in the kind company of Caroline, Anna, Geneviève, and Catherine, and with their valuable help and expertise, we opened the folders and went through all the available material by Riva, almost exclusively pencil-made drawings over tracing paper. Maybe too impressionistic in our approach, in most cases, we spent just a couple of seconds looking at each page; in others, half a minute; in very few, we took notes.

Tracing paper

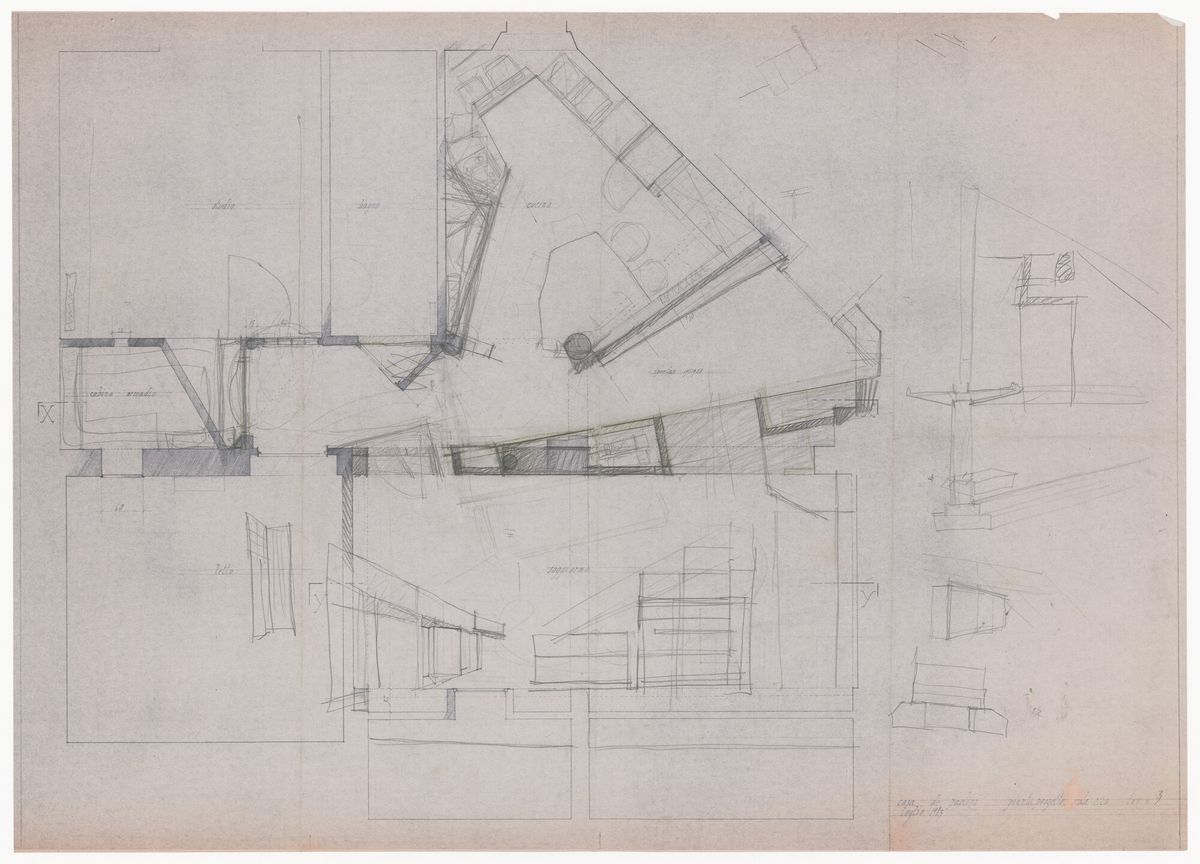

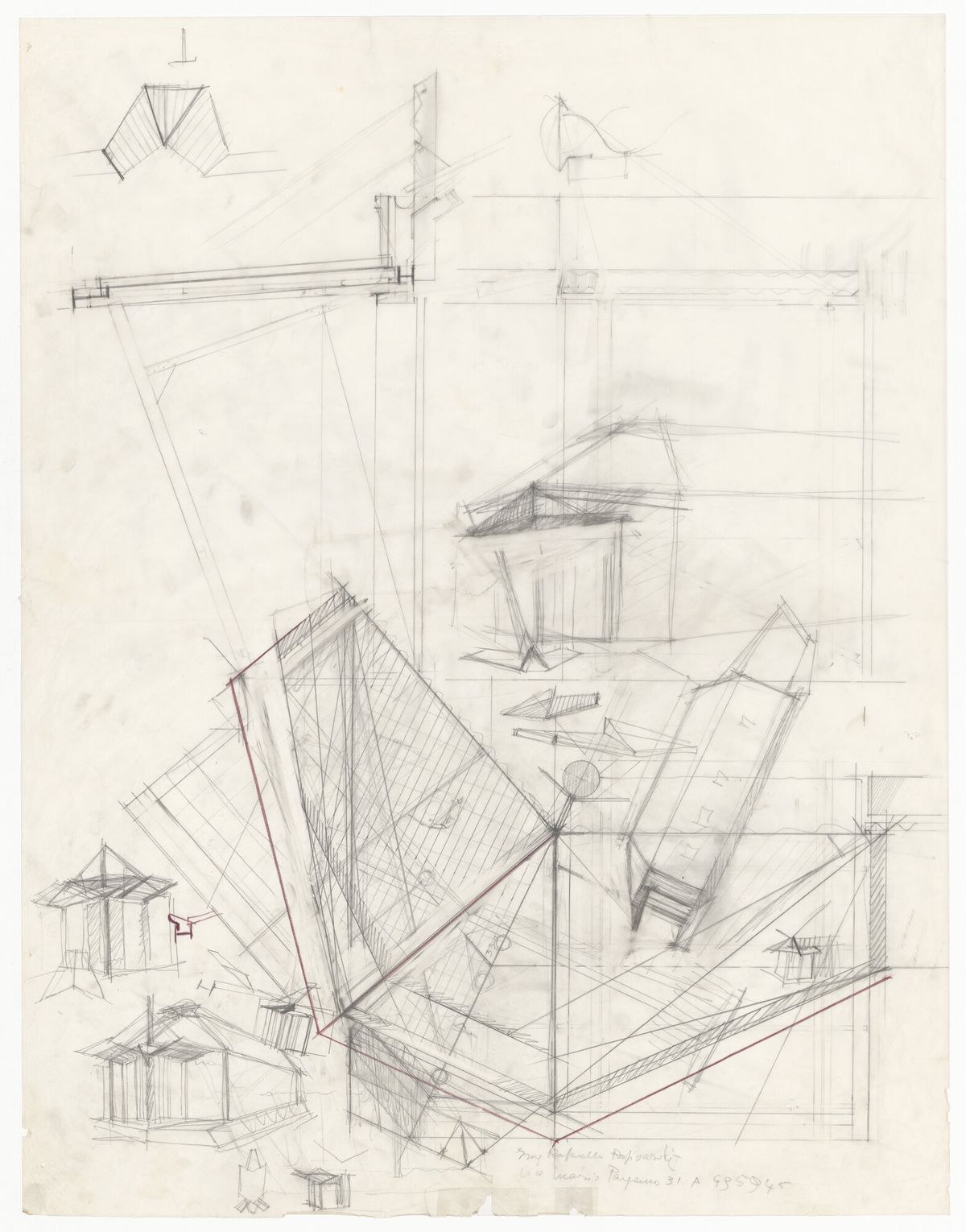

We could divide the drawings that we found in two main categories: execution details and insistent drawings. Once in a while, a few general plans; rarely, perspectives or spatial studies, or even material or colour studies, as the photographs of his works and his paintings might have suggested. Our initial impression was that we were viewing an archive of a furniture designer who was forced to deal with the space, and not the other way around.

Since we don’t believe in the immaculate conception of an architectural project, we are led to think that the archive we saw in those few days at the CCA was incomplete, previously curated by someone else who decided what to exclude future scholars from studying. No architect would start their production at that stage; at least for us, it is difficult to conceive so.

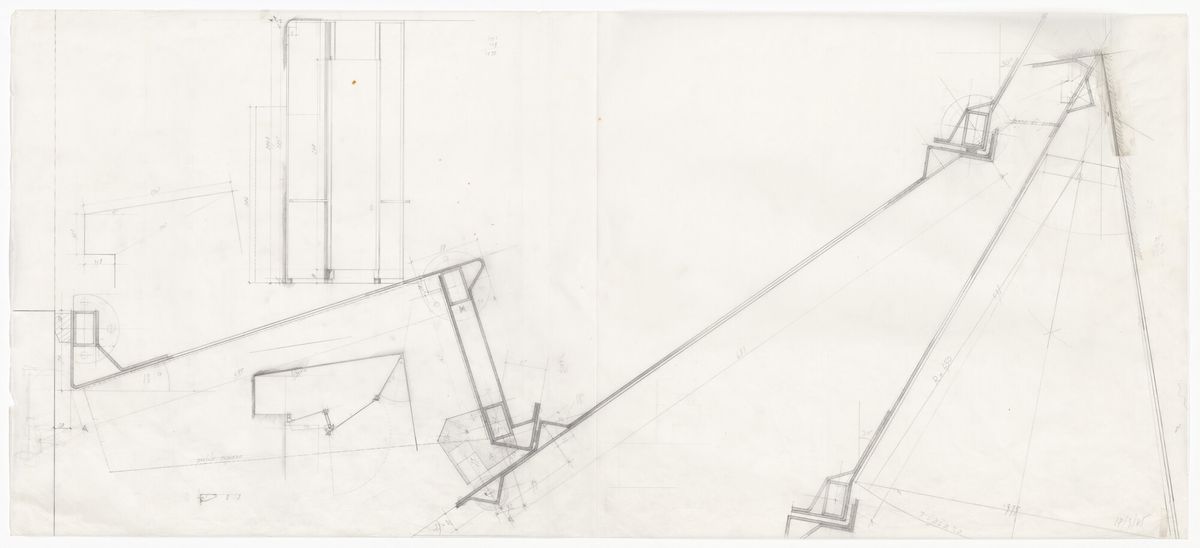

Nearly all the drawings that we viewed referred to projects that were both small in scale and residential. Apartments and houses, mainly, with a remarkable attention to small moments that usually disappear as life unfolds. Commonly, gravity centres were defined: a fireplace, a stair, a cabinet, or a balustrade. Several pivot doors were flawlessly drawn, detailed, questioned, re-drawn again, and again.

We like to believe scale doesn’t matter. Big buildings are often not great architecture; small buildings can and have changed the course of history; a room is a small city; and a city a big room. Maybe we think this because it fits us, but we are convinced it also fitted Riva quite well, and was declared in every line and intersection in the hundreds of tracing paper pages that we sifted through. The scale of what mattered to him was measured in the clarity of each line, be it a wall or a table, not in the size of the edifice it would create.

Topology

Over our discussions while navigating the archive, a certain kind of topology came to mind. Every detail, and every form, had several iterations—precise variations, often quite close to one another, as if the decision they represented was made a priori and the drawing was a trial-and-error exercise of translating them onto paper.

Most drawings were repeated five, six, seven times. At the same scale, occupying the same space on every page. Insistent drawings, often re-drawn over each other in an attempt to assert or confirm their validity. The weight of the author, and his struggles over the pages, was evident.

There was little or no variation of the proposed spaces. Rooms were defined, as if in stone, and only the pieces and objects inhabiting them were allowed to flirt with one another; a few inner elevations here and there, mostly to frame a specific shelf or staircase, and little inventiveness on the volumetric aspects of such rooms.

We occasionally discovered plans, and despite the secondary yet frequent drawings of each of them, no true experimentation was to be found. Like the rooms they represented, these plans were static, immutable. It could even be thought that these were all renovations of old palaces whose walls were not to be touched. As former students from Porto, as much as we prefer to avoid identifying as such, this was an uncomfortable set of drawings, as if a provocation to the idea of spatial definition per se. If form was where we had assumed we would start, a very different understanding of form was where we found ourselves. At some point the thin separation between space and furniture, and the drawings that referred to each, was to be ignored for us to proceed.

Technical notes

All the drawings we saw were made by hand, with pencil, even the most recent ones. Small signs of scotch tape in the corners, together with the long pencil lines, proved their genesis at a drawing table with the support of parallel bars. All done in the same style, with the same precision, almost as if all prepared by the exact same person over a forty-year span, with no inventiveness in their working process. We found very few free-hand drawings, as if the rigorous precision of a ruler was mandatory at all moments. In a few of the pages, small annotations referred to measurements and material references.

Contrary to what the images of the built projects suggested, colour was almost completely absent in the drawings we viewed. There were very few exceptions, a couple of highlights were visible in specific elements, although the colour used was not meant to represent the colour they would later have in their built form, being once again a diagrammatic expression. Looking at the available photographs of the built works, we are led to assume the paints, hues, and shades were decided on site, during construction; and perhaps, the use of colour at all was in limbo until such moments.

It was felt that each drawing took a long time to be done, probably with many cigarettes smoked in between. The exactness of each line, and the lack of variables between versions, suggested so. Each page was dedicated to one kind of drawing and the following pages would refer, reflect, and repeat the same drawing. Here and there, some xeroxed copies were to be found, just to, once again, be redrawn over themselves once more. Frequently, tiny textual annotations conveyed the multiple dimensions of the details being drawn – steps, handrails, shelves. As referred, very rarely, a perspective would support the main reflection on the page, appearing in a discrete manner in a corner; contrary to Siza’s, Riva’s pages were “closed” once the drawing they were supposed to present was complete.

Speculation. “A composer”

The available layers of the Umberto Riva fonds that we navigated represent an incredibly consistent group of drawings. Constant in their format, in their means, maybe even in their aims. It is a portfolio that refers to a very specific project methodology that was experimented with and repeated over decades with no apparent contradictions. It is persistent; if one was to take a random page from a random folder, it would be difficult to guess to which time or project it would belong. Maybe that is a great achievement, a kind of all-encompassing consistent inconsistency.

Perhaps, Riva’s projects have no age, and don’t belong to a specific time. From the quasi-brutalist early vacation homes until the light steel staircase of Casa Righi, all could have happened in the early 60’s, in the late 90’s, or somewhere in between. The deeper we dived into his drawings, the clearer that idea became.

Going back to the start, form—in its most direct expression—was there, that is evident. But the autonomy Riva referred to, was not the same as what we were looking for, or at least not in the same way. Indeed, forms through his drawings were freer than most, but were still a means to an end, not an end in themselves. Each angle, and the intersection of such angle with a careful curve, was there to provide a shelf and bring the frame of a window a bit further, not to be just “a drawing” as we had naively assumed.

Riva was a composer. From the available materials, it is difficult to imagine otherwise. No strong concept or one main idea-driven architecture would produce these spaces and objects. In the design process, his instinct had to be there, making him fundamental, the constant. We have to wonder about his theoretical basis for winning arguments (with clients or with collaborators in his practice): were there some? Some drawings leave an idea of a highly precise accidental method, if such could exist. His way of developing a project was dependant on his own intellect and was, probably, very hard to pass on to his successors as a method. Maybe, we wonder, that’s why his architecture has been less known compared to others from his generation. His built projects were the final stage of his work, allowing for contemplation over rationalization. He kept insisting on each drawing, even if we couldn’t distinguish between the endless iterations; but maybe that was our problem, not his.

Filipe Magalhães and Ana Luisa Soares (Fala Atelier) were in residence at CCA in August 2023 as part of Find and Tell, a program that promotes new readings that highlight the intellectual relevance of particular aspects of our collection today.

Related residency