When I Think of Home

Reanna Merasty, Johanna Minde, and Robyn Adams recollect childhood memories of growing up in the North

The three texts collected here were written for the book Towards Home: Inuit and Sámi Placemaking, to be published by the CCA, Valiz, and Mondo Books in April 2024. The three authors participated in the Futurecasting workshop organized in preparation of the exhibition ᐊᖏᕐᕋᒧᑦ / Ruovttu Guvlui / Towards Home and discussed in this other article.

Reanna Merasty: A Nihithaw Upbringing

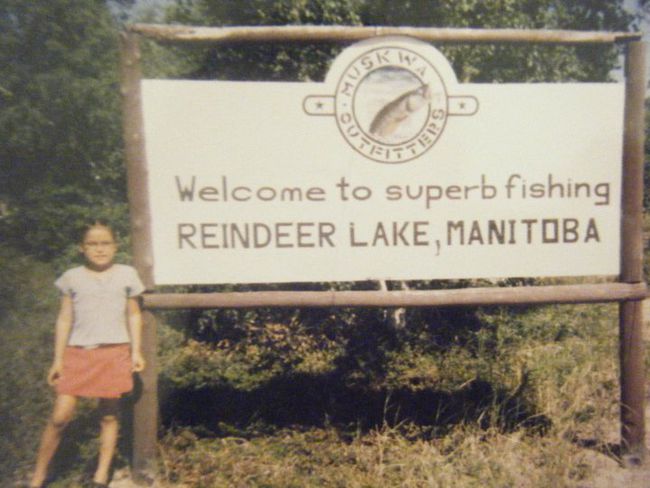

My fondest recollection of my home involves standing on a dock, at my kin’s remote island in the middle of Reindeer Lake in Northern Manitoba. The dock is a simple but elegant construction created from local lumber, stones, and rope, hovering over the water, waiting for a boat to arrive. As I look down over the edge, beyond my wet sand-ridden feet, I witness the clear water as gentle ripples move across its surface. The only thing I hear is the soft wind interacting with the water, the trees bustling along the shore, and the faint sounds of a motor in the distance. As the motor gets louder, I hear the boat begin to crash against the peaks of the rough open water. It then clears the threshold between rough and calm, passing the tree line, and begins to slow down. At the back steering the boat is my papa (grandpa), with a green camouflage cap, long brown beard, and a fresh lake trout at his feet. At the centre is my kookum (grandma), sheltered with a layer of blankets and blue tarp, with her short grey hair peeking out of a toque. Both give a simultaneous wave and warm smile to me. When they arrive at the dock, they are sitting amongst a backdrop of pink and orange hues as the sun nears the line where the water meets the sky, getting ready to welcome the deep atmosphere and the northern lights’ spirits.

These senses and sights are what defined my upbringing as a nihithaw iskwew (Woodlands Cree woman). They are recurring recollections that influence the way that I interact with the world, and how I represent my home.

Home, not merely a building, is an entire environment. Encompassing all forms of life, home is more than a person and includes all of creation. It includes the animals that live alongside us, the soil that is beneath us, and the plant life that surrounds us. Home is the range of sensorial experiences tied to all living beings in a place, and to the living beings that sustain and provide abundance for our lives as humans, all of which are examples of the love that the earth provides us.

The gentle and deep-rooted connection to the earth from my childhood is still instilled within me, and it has shaped my values. These values are based on the principle that we should be working together in reciprocity for, rather than against, the earth—a principle so eloquently explained by David Abram:1

-

David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human World (New York: Pantheon Books, 1996), 121. ↩

“By invoking a dimension or time when all entities were in human form, or when humans were in the shape of other animals and plants, these stories affirm human kinship with the multiple forms of the surrounding terrain. They thus indicate the respectful, mutual relations that must be maintained with natural phenomena, the reciprocity that must be practiced in relation to other animals, plants, and the land itself, in order to ensure one’s own health and to preserve the well-being of the human community.”

I now work in the field of architecture, and although my thought process has been inherent, my experience is not similar to that of most people in the profession. For most, they have lived without access to land, and lack an in-depth relationship to it. I believe once that relationship has been enacted and others understand the notion of its importance in sustenance, they will be able to work towards architecture that protects, honours, and respects the land. As Robin Wall Kimmerer states, “knowing that you love the earth changes you, activates you to defend and protect and celebrate. But when you feel that the earth loves you in return, that feeling transforms the relationship from a one-way street into a sacred bond.”1

-

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013), 124. ↩

To assist in this thought transformation in designers, I have developed seven guiding design principles inspired by my upbringing:

1) Honour the land, understand what is there and what it has to offer.

2) Practice humility, realize that the land is greater than us.

3) Cross-process with place, research the local conditions, the climate, and the environment.

4) Tread lightly, have a positive impact and be sensitive.

5) Light for energies, ask how all living beings in a place are interconnected, and how we can showcase these relationships.

6) Foster reciprocal actions, follow the rule of giving back ten times more than you take.

7) Prioritize heart-work, work with kind heart, mind, body, and spirit.

These principles are created as a process to recognize our humility, to include other living beings on this earth in our design processes, and to collectively work with the environment that surrounds us. These principles will allow designers to become aware of the values and knowledge that we Indigenous peoples have been voicing, and the experiences from the land that we are working to protect.

Go experience the love of all forms of life that surround you,

Listen to words that the wind speaks,

Feel Mother Earth breathing beneath you,

And all the energies that she creates,

Allow the stories of the land to influence and guide,

Create with kindness and warmth of the heart,

Forward to another.

I am designing for the senses and sights of my upbringing, to ensure that my children, and the children of many generations to come, can experience the beautiful remoteness of their home territory. For my kookum and papa, whose relatives walked along these waters and protected these lands.

Johanna Minde: Returning to Nature

Mica has been used in several Sámi areas along the mountainous Norwegian coast for hundreds of years. In Stuornjárgga, a place I call home, stories have often referred to the layered stone as “poor man’s silver,” an allusion to its traditional use as decoration for Sámi clothing among coast-Sámi families. On some old belts from the area, as I have seen, mica has been used instead of silver buttons. Whether or not the storytelling is true, the application of mica as decoration is a practice that uses natural resources in a constructive, sustainable, and culturally relevant way.

And so I am taught.

When I think of home, I think of the area that nurtures my family, and about the important people in my life. But home is also an area full of natural resources that I have the opportunity to enjoy and harvest from. It is the place where I gain inspiration, and where I collect material for craft and for living. When I make duodji, the traditional Sámi handicraft, using nature’s resources such as mica, I am able to express myself and elaborate upon who I am.

This process of collecting often leads me to ask myself what interventions the landscape can recover from after human needs are met. When I take material from nature, I make sure not to pick everything in one place; I want there to be more resources left for the next time I, or someone else, needs them. The Sámi customary practice of leaving as few traces behind as possible and only taking the material from nature that you need for the day is both valuable and beautiful to me.

I like to think that this way of understanding the use of natural resources can be transferred to a way of thinking about architecture. When building in Sápmi, it is vital to understand the function of the building in its context. Traditional Sámi constructions are site-specific, characterized by their ability to adapt to the landscape and the climate, and built with local materials for use within their surroundings. A building constructed with natural materials has a natural life cycle; when it is abandoned or moved it will leave very few traces behind. The lifespan is limited, and the building can return to nature. When using modern building methods, restoration and recycling can be complements to this process of returning to nature. By using site-specific and natural materials together with components that can be dismantled and relocated, it becomes possible to restore the landscape in a sustainable way, returning it to a state close to its origin. Restoration offers flexibility, where form and function can work together.

Returning to nature requires a reciprocity between material and context that exists at every scale of Sámi creation. When Mica is used in Sámi handicraft, the mineral is divided into small flakes and fastened between two pieces of fabric or leather that are then sewn together. The fragile and volatile nature of mica thus supports a new function, one that is adapted specifically to the mineral’s properties. Through this use, mica becomes a symbol of home that I can carry with me. By wearing a part of my home in my clothes or belongings, home will always be nearby, wherever I am.

Robyn Adams: In the Forest after I

For my granny, Reynalde Adams (née Curé) 1942–2023

All my mother’s spirits woke me.

My breath changed—

became more full, heavy, but light from within.

They showed me their stories as the cedar from the fire crackled like my grandfather’s stutter, the gift of medicines burned bright.

Filled smoke circling, moving.

I could see them and feel them. I asked (inside) for them to see me—to see if they could hear me.

Now, my body more, my body yours,

and while my feet were on the forest floor, I saw their memories in my memories.

My granny sits as a child, I sit as a child.

She knows the land through her hands. She picks berries in the bushes along Rat River. I pick berries along the Red. Spending the hours of the day in the sun, tanned kissed skin. She and her sisters laugh as they fill up buckets poor maamaan.

We live together in a room hugged by wood harvested from ni paapaa which grew just outside their window. The logs wrap our home like thick knuckles around chalef changeant, a dovetail home with patches of cement between each log.

Fingers pull the roots

and grab

like cutting the umbilical cord.

Shaking off the soil, the dirt falls

and sprinkles on the other plants

like sifting flour.

You remember those flour sacks everywhere.

The prints on dresses washed out with coal.

Your hands stitch each thread along the seams,

like the garden that you planted—

seamed together because of you.

The wheels of leu shaaret

circle through the paths you made over and over again,

as if your feet mark the dirt

like mouse tracks in snow

like airplane contrails

like niskak in the Milky Way.

But toes and wheels stick to the soil,

compact the soil,

change the soil,

and take longer to fade.

Displacement fade.

The land you tend is plotted by activity, the movement of your siblings, your dad’s horses, the wheat felt by your hand.

But even the way you farm is different.

You know the land through the animals, the horses, the trap line.

Through lii zannimoo faroosh.

Michif / English

poor maamaan / for mother

ni paapaa / our father

chalef changeant / wolf willow

leu shaaret / Red River cart

niskak / geese

zannimoo faroosh / wild animals