Work Smart, Not Hard

Hester Keijser, Luuk Smits, Charlie-Anne Côté, Emma Rath, and Victoria Addona discuss construction videos on social media

The following conversation took place in January 2024 during research discussions for the exhibition madskills: Self-Documenting Construction on Social Media, which runs in our Octagonal gallery from 7 June 2024 to 27 October 2024.

- Charlie-Anne Côté

- How did you first encounter construction videos on social media? What interested you about them?

- Hester Keijser

- I first came across construction videos while scrolling on Instagram—the good ones immediately grab your attention. Through the algorithm pushing similar content in my feed, I discovered a whole world of these short clips made by people working in construction that others are actively commenting on and sharing. I was intrigued and decided to dig a little deeper into what seemed a new genre of visual representation of the construction industry at large. The clips range from videos of mining and resource extraction to ones taken by suppliers and those doing the construction work: operators harvest wood, level ground, bend rebar, produce metal components, mount drywall, or paint buildings. You can’t always tell what’s going on in them, but they often show a fascinating part of the construction process, or somebody explaining something that you didn’t know about; they kind of fit in the category of how-to videos, but not quite.

Architecture is very much involved with construction, but these clips focus on informal and daily aspects of worker culture that we infrequently see or consider. Currently, very little is written about this phenomenon, yet it’s extremely popular—thousands of videos receive millions of views and generate engagement from viewers worldwide. Although I’ve noticed a growing architectural interest in workplace realities in the construction industry, there’s a bit of a mismatch in terms of our access to this type of imagery or an existing framework that allows us to reflect on it in meaningful ways. - Luuk Smits

- I became fascinated by these video clips in a similar way. During a residency at the European Ceramic Work Centre (EKWC), I remember scrolling on social media during my breaks, like many of us do. When I wasn’t working in the studio, I was walking outside, taking snapshots with my phone of construction sites, and making visual notes. Like in your case, Hester, the algorithm may have registered that I was looking at tools or materials for my project and fed me these videos.

In that period, I was working and researching underground infrastructure in cities and, as a result, I started observing patterns in the type of social media videos I tended to see. After a couple of years of collecting these videos, I started building an archive using keywords and found a way to work with them in my art practice, which generally focuses on how things work the way they do.

Then, in 2022, I did a residency at the Zentrum für Kunst and Urbanistik in Berlin with a proposal to work on the site, because the building—an old train station—was under construction. I thought it was an amazing opportunity to live and work on a construction site—I’d wake up with the sound of drills early in the morning. At that time, I started working more and more with the social media clips I had collected over the past years. I printed out thumbnails of these videos and began to edit them as an intuitive way of making visual associations, grouping videos that reminded me of similar actions. This formed the basis for Assembly II, a video installation I presented on the construction site, bringing together construction work and material production. - HK

- When you shared one of your videos with me, I saw that your editing method revealed something about this phenomenon that isn’t so obvious when scrolling through these clips in the apps, almost like building an underground map of these construction videos linked by different themes and stations. Figuring out how to manage them is remarkable because it’s so difficult to manage social media content—the apps and algorithms want to curate it for you, but it’s harder to do the reverse.

- LS

- The edits are also snippets of how visual minds work. The videos are quick and seemingly endless; when you’re flicking to another clip, it’s almost as if you’re already editing it. Editing these clips is a deeply creative process because I can follow the content and materials or the workers’ movements to link different videos. And other narrative layers can be added by collating the videos to tell an overarching story.

- HK

- Whereas an architect might feature a finished structure in their portfolio, these short videos are more focused on the process, work, and materials that are involved in building.

- Emma Rath

- Yes, they make the invisible visible in many ways. By taking us into construction processes, they allow us to imagine what’s between and beyond the walls of a structure. They also show how the same outcome can be achieved in many ways—they show so many styles of movement and making. By tracing their proliferation, you can also map how techniques are adapted and knowledge transfers.

- HK

- There’s much ingenuity involved in construction processes. Many workers must find on-site solutions with available tools; they can adapt to a brief by creating rebar with homemade tools or building foundations in a way that works with the site.

In North America or Europe, construction sites are often obstructed from public view, largely for safety reasons. Maybe a little peephole lets you look in, and you can see cranes moving around, but the site is far removed from the casual viewer and their involvement. I don’t feel I have any say or insight into construction processes in my built environment. Huge companies are usually directing this corporate kind of production, which is organized between businesses, landowners, and the government, and presented as an abstract process—at most, you’ll read an announcement about a new build in your local newspapers.

But in these social media videos, especially those focused on construction in countries with more informal practices and regulations, I often see whole communities involved in building processes. The construction site is more open and therefore more accessible. It’s much closer to your daily life, which gives people a more tangible sense of agency over what goes up in their built environment. - LS

- Your reference to informal practices reminds me of the construction site in Berlin where I worked. Once, as I was passing by, I noticed that workers were pouring concrete in a DIY way: they made a gutter out of a wooden slab to transport the concrete to a place the pump couldn’t reach. I started taking a video with my phone but the worker controlling the pump asked me to stop; he said that his boss wouldn’t be happy if he saw the video because making an improvised gutter was too risky.

- HK

- That’s another thing about these videos—you have no idea about regulations on these construction sites. We have no idea how and where these workers may be cutting corners.

- HK

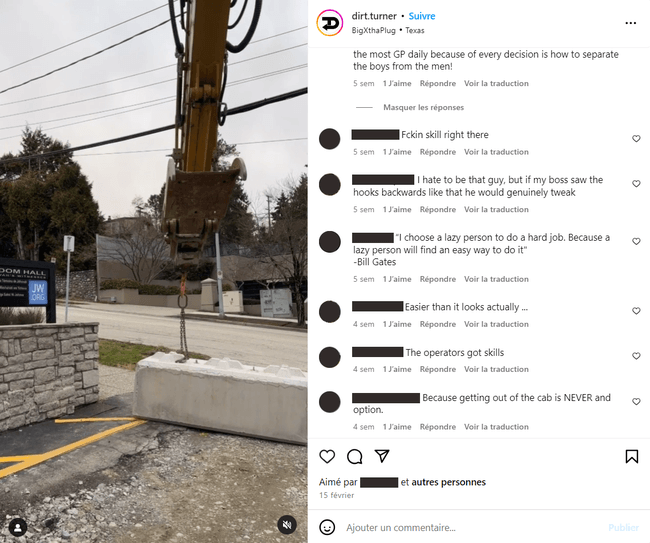

- The most important difference between a photographer and a construction worker making these videos is that construction workers can choose to document what they want to share about their work and how they portray themselves. I think there’s a natural match between social media and the construction industry, in the sense that there’s a performative aspect to construction, while Instagram and TikTok are very much about self-documenting and performing for a camera first and then an audience. In a way, the construction site is a stage, so it has this aspect of a performance space in which a worker or a machine can highlight a certain skill or outcome.

- ER

- These are long, repetitive days on the same site together. I think the joyful choreography of construction work and the playfulness these videos often capture also infiltrate their reception; they build a community space of pride, positivity, deep interest, and excitement in learning and sharing.

- Victoria Addona

- Have you noticed some recurring conversations in the comments?

- LS

- Viewers often want more information or clarification. They ask questions about what’s going on, or why someone is doing something in a certain way.

- HK

- Yes, the audience is also a lay public fascinated by construction techniques and technologies. They don’t always get an answer. Sometimes they’ll also ask utilitarian questions: “Where can I buy it?” “How much does this machine cost?” Comments aren’t often concerned with what’s being built or the architect, although they might express appreciation for design solutions.

- CAC

- “Work smart, not hard” is a recurring comment.

- HK

- Yes, safety is a recurring subject in the comments. They’ll express platitudes about work safety, like “take care of your life, it’s more important than work.”

- ER

- Or fire emojis. The engagement is overwhelmingly positive and gives the sense that the community interested in these short videos appreciates the skills displayed and the content produced and wants to share their amazement with the makers.

- CAC

- We should be mindful not to romanticize social media communities, because of course we also see comments that aren’t so nice or respectful. There are trolls online and sometimes sexist or racist threads in the comments section of these videos. Some accounts republish content produced by those on-site with no regard for its copyright to generate traffic on commercial pages or links that infect your computer with ransomware. Workers who choose to represent themselves and their work on social media platforms might see the content circulate with no respect for their authorship.

- HK

- On the other hand, this circulation is part of the game: once you throw content into a social media sea, you must let it lead its life. Maybe some creators are happy to be picked up by a larger aggregate account with millions of followers—as a source of affirmation.

- ER

- Maybe these creators’ agency concerns their decision to post something online; they choose to put their videos out there and understand that they may swim and flow in different circles and be appropriated in unintended ways. Their actions are driven by wanting to be seen as sharing something on the platform, not necessarily claiming recognition or authorship.

- VA

- Thinking about how your interest in this genre started, Luuk, with a kind of open construction site that you could peek into, makes me think there’s something so fundamentally fascinating about watching machines and those who operate them, even from a young age.

- LS

- Yes, and pleasure in observing a space where people and machines work together—in which rhythmic, repetitive actions almost turn workers into a type of machine, or the machine becomes a prosthesis for the human body.

- HK

- We have so many building toys for children, so we encourage their interest in construction and making things from a young age. But when they reach the age of choosing a profession, they’re mostly dissuaded from construction.

- ER

- “Go be an architect.”

- HK

- Yes, be an architect or a designer instead! We introduce construction to children because we know that machines and their processes are compelling and educational, but then we often block this interest. To a certain extent, this is the case with the machines and construction techniques foregrounded by these clips—they’re fascinating, but there’s a general disregard for the skills these workers have and generously share. The people posting about their work want to counter this disregard and advocate for their industry to show that there is much more to these jobs than what people generally imagine. A huge labour shortage is looming in the industry as the baby boomer workforce is retiring. Turning to social media is a way to engage a younger crowd and show them this is a viable career option.

- HK

- People in these fields of work can get significant hate in the comments, which can’t be easy to digest, but let’s remember that our consumption patterns and the global economy driving them create the need for extraction at this scale. After watching a lot of these videos, you have this sense that whole forests are being destroyed, the earth is being eaten—they picture an aggressive attack on natural resources. This impression becomes very visceral when you see a constant loop of machines cutting up mountains or harvesting trees. If there’s anything to take away from watching these construction videos in bulk, it’s that we’re facing a herculean task to change how we produce our built environment and make the construction industry truly sustainable. Seeing the eagerness and generosity with which the operators on the ground share their knowledge, experience, and skills, despite the inequalities and power dynamics that are at play in the construction industry, gives some measure of hope.