Westpen is conceived as a diagram

Sofia Nannini on Cedric Price’s project for an animal handling unit

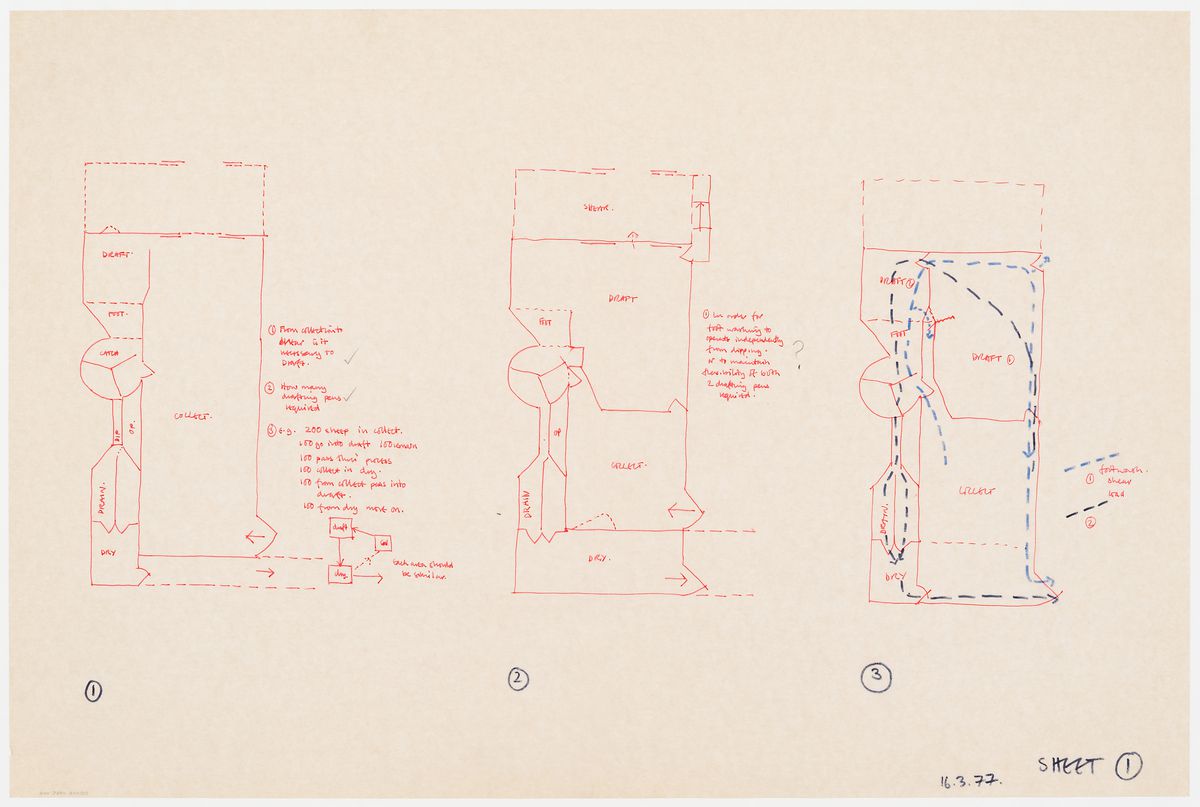

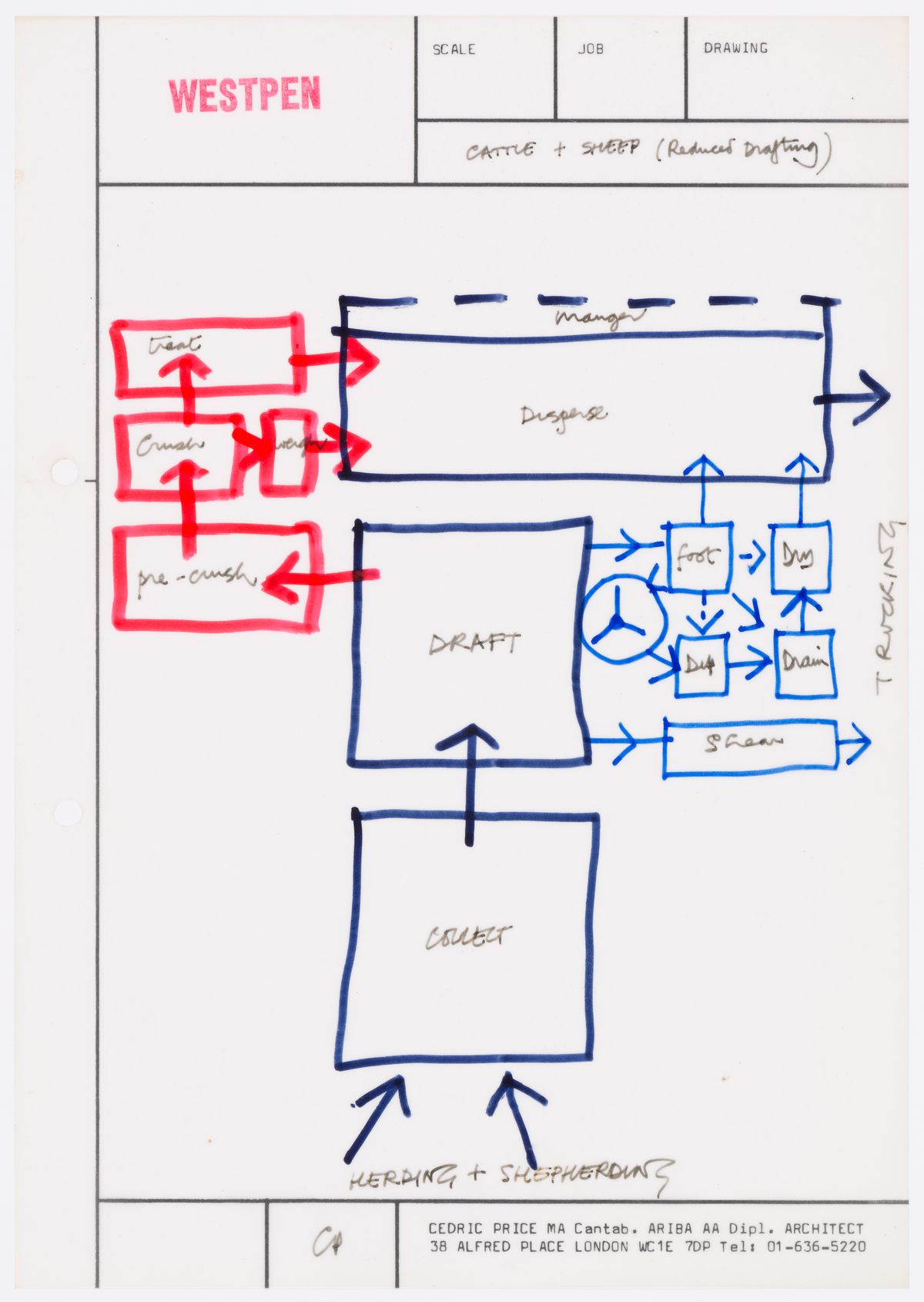

Westpen is conceived as a diagram. The first drawings of Cedric Price’s unexecuted project for a cattle and sheep handling unit, dated between March and May 1977, combine doubts and sketches that draft possible spatial solutions for the livestock corral. These initial sheets explore some layouts with different areas to collect, draft, catch, dip, drain, and dry the livestock owned by the client, the politician and businessman Alistair McAlpine. McAlpine’s was a small operation of white English cattle and St. Kilda sheep.1

Animal husbandry is chiefly a medical practice. At the core of Westpen stands the fear and danger of zoonotic diseases: cattle must be drafted for weighing and treatment; sheep must be dipped in a chemical solution for protection against parasites, and for shearing. At first the architects seem to imagine a shared spatial solution for both kinds of livestock, going through the same paths, from drafting to drying. Then they start to distinguish the two alternative directions for the corral: one for crushing, weighing, and treating—for cattle—, and the other for shearing and dipping—for sheep. At the end of each route, two arrows point to the final step of this process: “trucking” which presumably take the animals back to the pastures. At first, Price’s diagrams are very abstract: squares connected by arrows. A function for each square, and monodirectional arrows connecting them. Then, the arrows connecting each square become routes: sheep and cattle are allowed to follow very strict paths according to what is needed from them by the operators. In the drawings for the renowned Fun Palace (1960–66), arrows suggest unexpected and elastic possibilities of human circulation.2 In the McAppy project—also commissioned by McAlpine in 1973–76—, flow charts serve the purpose of improving communication, security, and satisfaction on the construction site.3

Within the fences of Westpen, animal movement should be foreseeable. Each route can only be travelled forward: there is no leeway for the animals, no turning back. Every arrow and every line are a forced path. Architecture is reduced to a boundary and to the routes allowed within it. The paths traced for sheep and cattle may seem to fulfill the modernist dream of “frictionless living,” as defined by Catherine Bauer while discussing Alexander Klein’s diagrams for residential layouts.4 Or is this Taylorism applied to animal bodies? This opens more questions: can farmed animals be conceptualized as biotechnologies, workers, factories, or products?5

-

Corinna Anderson, “Architects in Agriculture,” 1 June 2018. ↩

-

Samantha Hardigham, ed. Cedric Price Works 1952–2003: A Forward-Minded Retrospective (London: Architectural Association / Montréal: Canadian Centre for Architecture, 2016), 47-85. ↩

-

Hardigham, Cedric Price Works 1952–2003, 399-405; Giovanna Borasi, Andre Tavares, What About Happiness on the Building Site, exhibition, CCA, 9 February – 14 May 2017. ↩

-

Catherine Bauer, Modern Housing (Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1934), 203. ↩

-

Edmund Russel, “The Garden in the Machine: Toward an Evolutionary History of Technology,” in Industrializing Organisms: Introducing Evolutionary History, edited by Susan R. Schrepfer, and Philip Scranton (New York/London: Routledge, 2004), 8–11. ↩

This text is an excerpt from an upcoming volume in the CCA Single series resulting from Sofia Nannini’s participation in our 2023 Research Fellowship Program.