Forms that Fascinate

Saloni Mathur on the Aditya Prakash fonds

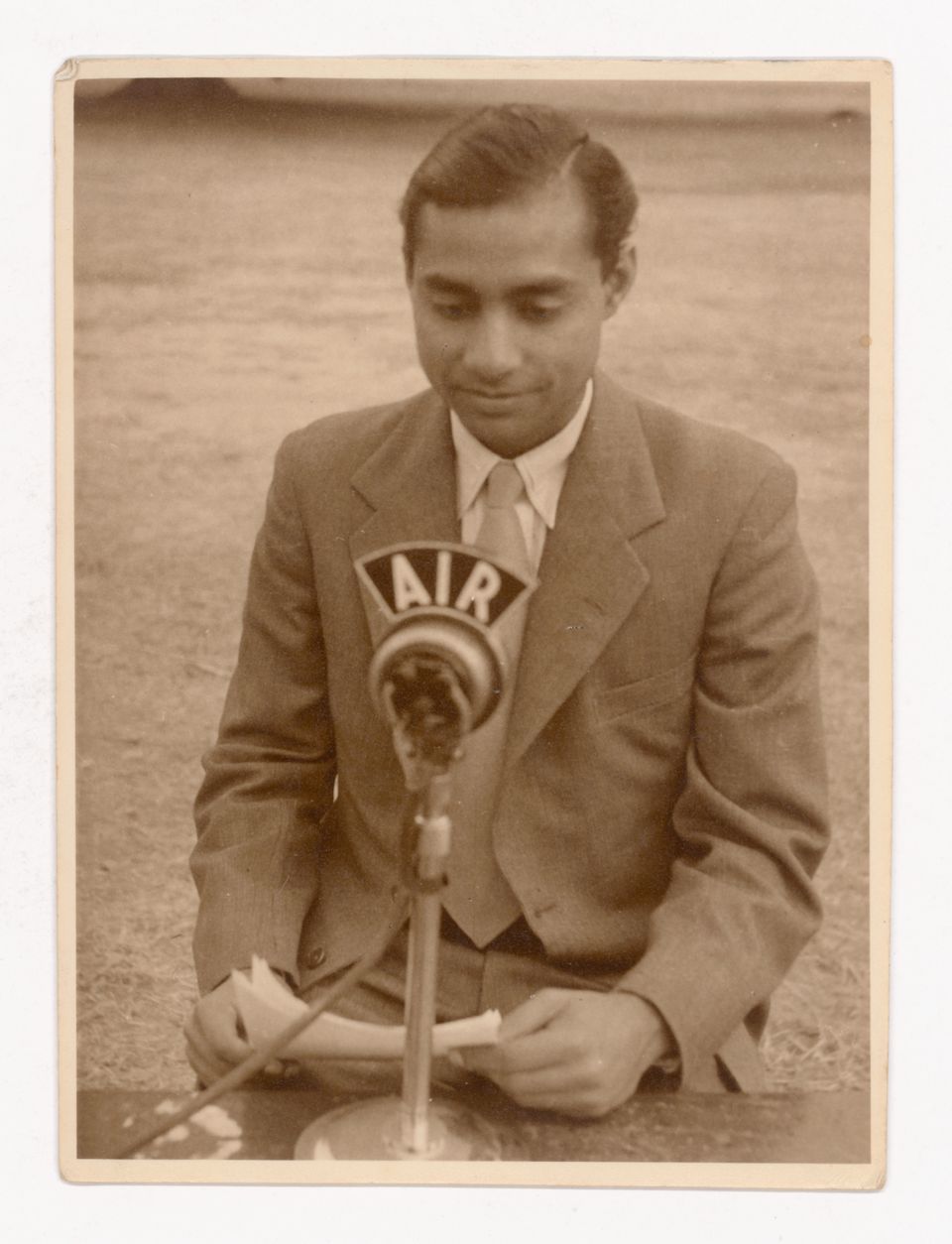

A striking photograph from the 1950s in the Aditya Prakash fonds conveys the sense of a young man on a mission. Immaculately dressed in suit and tie, and fresh from his architecture studies in London, Prakash is poised in front of a microphone bearing the insignia “AIR.” This was (and still is) the abbreviation for All India Radio, the state-owned public radio broadcasting service established in the Indian subcontinent in 1936. Behind him in the photographic frame is a vast arid field stretching endlessly into the horizon. As part of the team of junior Indian architects invited to participate in building the new capital city of Chandigarh, Prakash was tasked with informing the public through a live radio broadcast about the project they had embarked upon in this remote, rural setting in the northern state of Punjab.

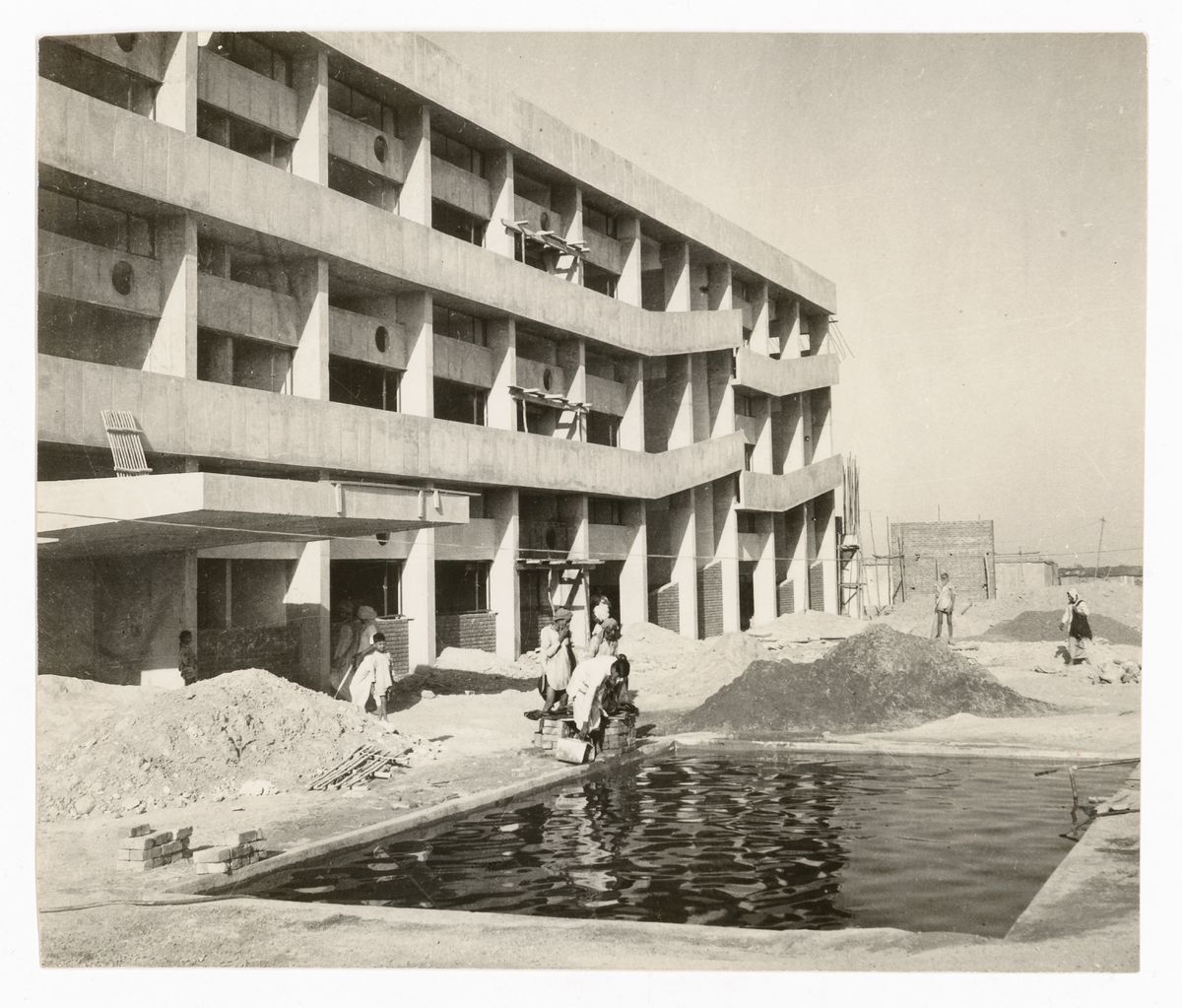

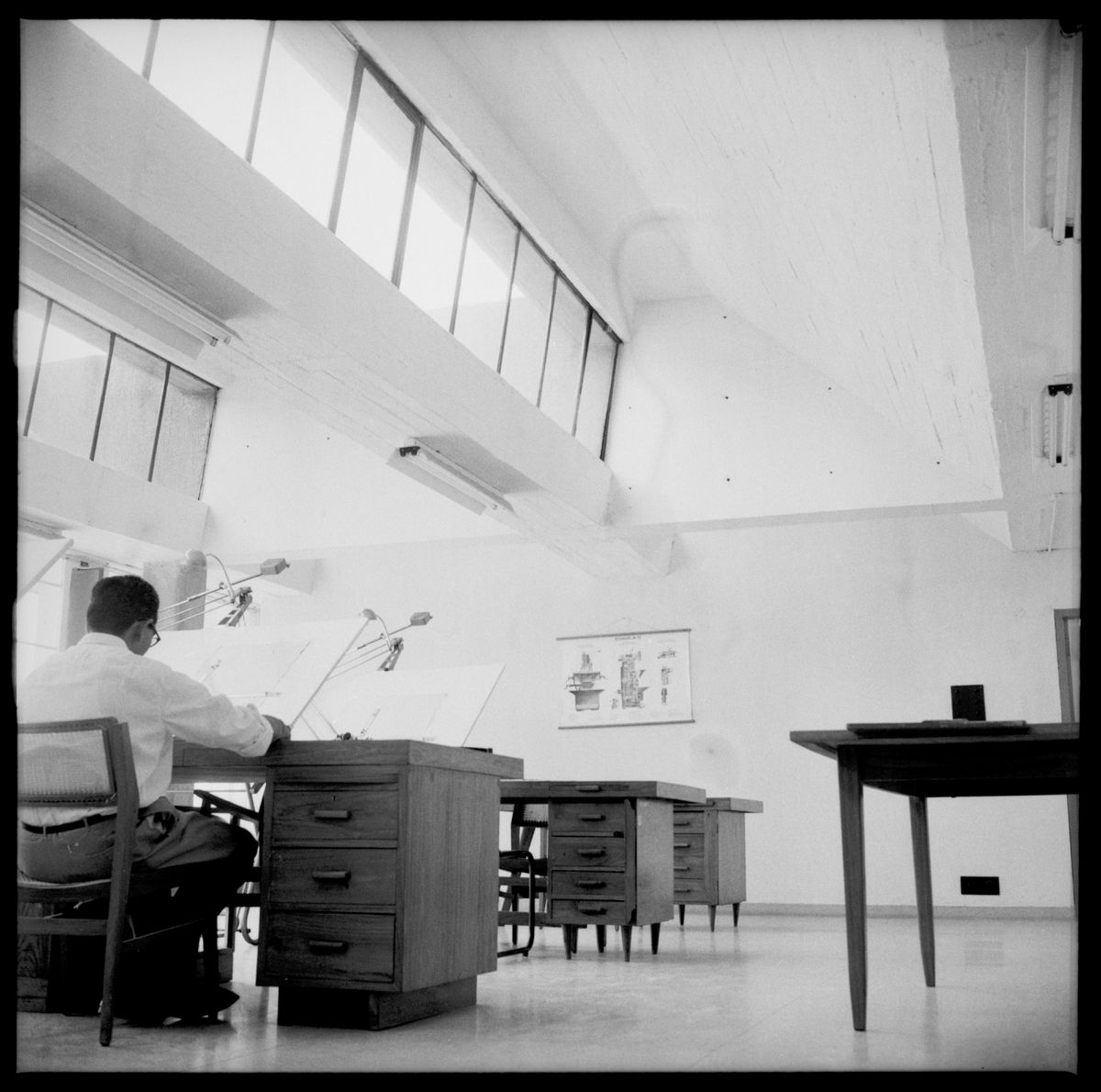

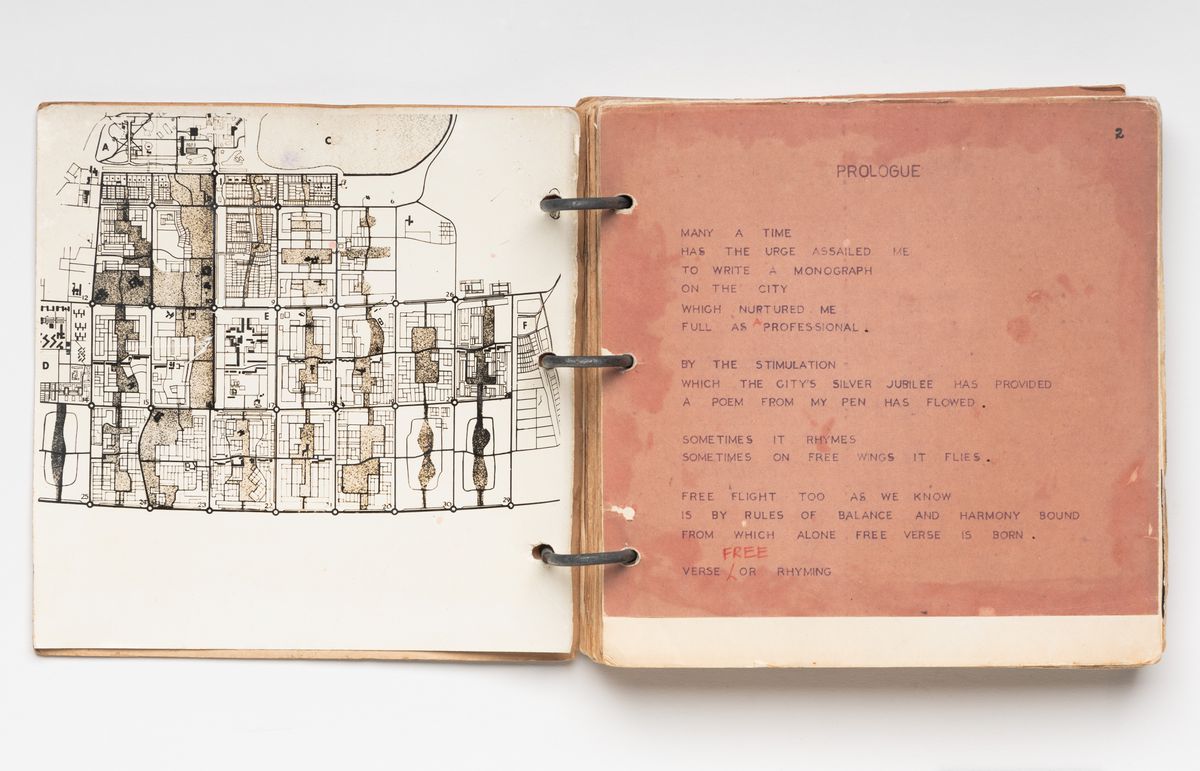

Prakash, who designed some sixty buildings throughout north India during his life-time, is a fascinating and underexamined figure within the story of twentieth-century modernism. Growing up in the colonial era, he was in his early twenties when India gained Independence from British rule. He left the subcontinent on 8 August 1947, one week before Independence was achieved, to pursue his studies in art and architecture in London and Glasgow, and would remain in Britain for the next five years. In 1952, Prakash received the opportunity of a lifetime: to join the audaciously ambitious project spear-headed by India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, to build a new capital city for Punjab. The region was still reeling from the bloody violence and refugee crisis of Partition a few years earlier, and had lost its previous capital, Lahore, to Pakistan in the division of land that resulted in two new nation-states. Nehru wanted a modern city for Independent India, a future-looking landscape, as he stated, “unfettered by the traditions of the past,” and he famously commissioned Le Corbusier in 1951 to serve as chief architectural advisor and author of its master plan.1 Nehru further conceived of the project as a laboratory for education and professional development, and envisioned that the senior architects from Europe would help to train their Indian counterparts. It was a prescient vision. As the “junior-most of the junior architects” from India recruited for the team, Prakash went on to work closely with Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Maxwell Fry, Jane Drew and a large staff of Indians for the next decade, passionately absorbing the principles of modernist aesthetics that would meaningfully determine the course of his life.2

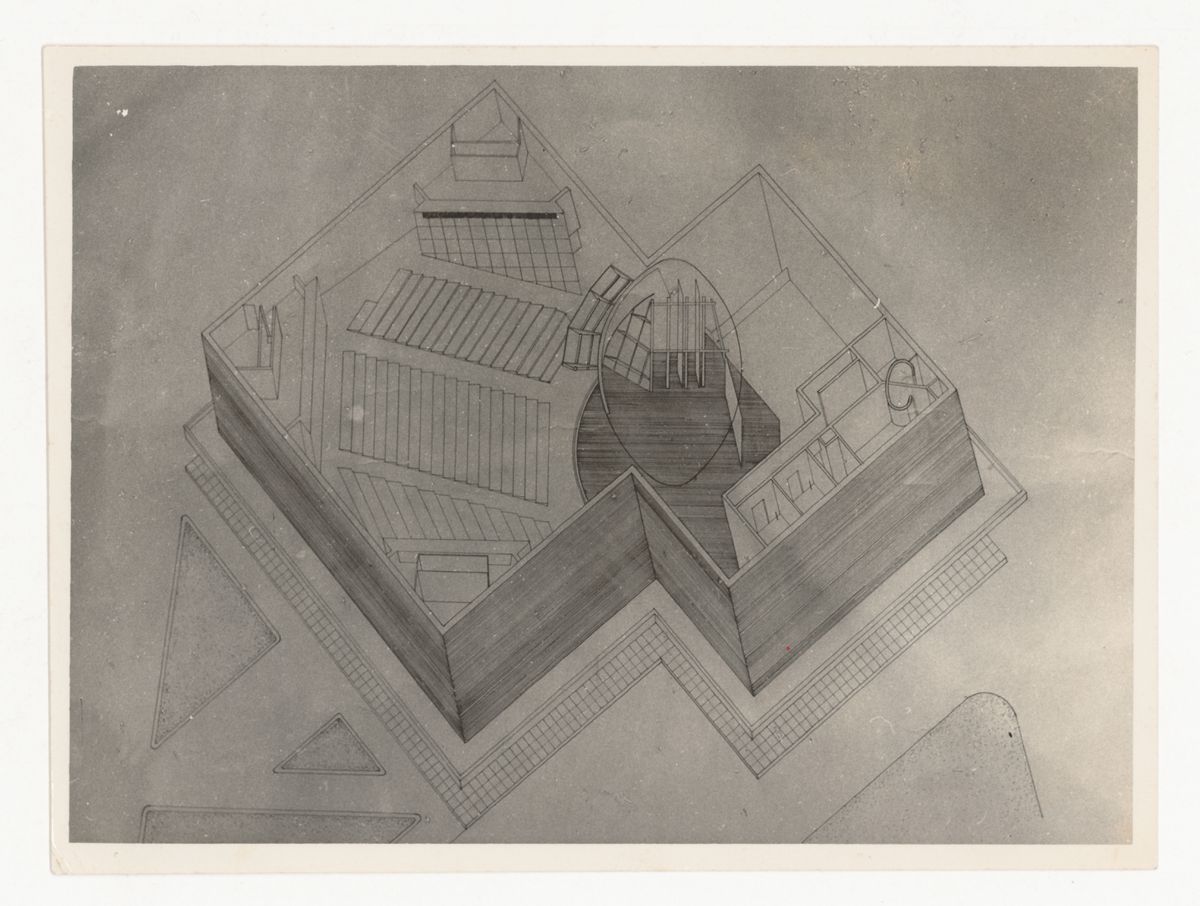

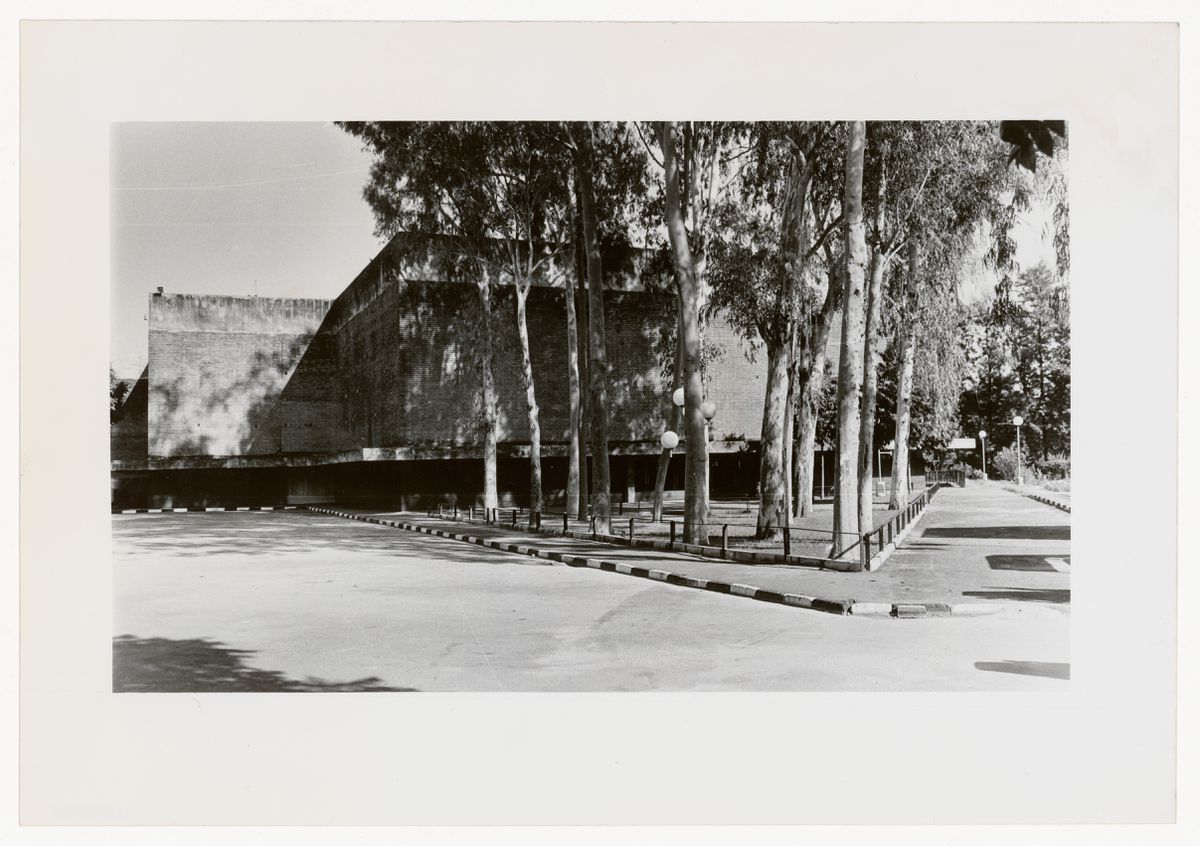

Prakash might thus loosely be seen to belong to the generation that Salman Rushdie dubbed “Midnight’s Children,” in his famous allegorical novel by that title. Rushdie’s reference was to the generation of Indians born on the cusp of India’s Independence from British rule (i.e., on the stroke of midnight, hence my emphasis on “loosely”), whose individual journeys nonetheless became inextricably entangled with the larger collective project of nation-building. “So far my profession was my cause; now India too is my cause,” Prakash wrote in his diary in 1947, signaling the mixture of happenstance, fate, and purpose that drove his extraordinary journey. Prakash would go on to build theatres, universities, cinemas, and schools of art, architecture, and agriculture, all reflecting this sense of earnest investment in the cultural fabric of the nation. His major projects in Punjab—like the Tagore Theatre designed in 1961 for the centenary of Rabindranath Tagore and the three campuses of the Punjab Agricultural University (1963–1968) undertaken in the heyday of India’s Green revolution—repeatedly point to Prakash’s commitment to modernism at a time when modernism itself in India could not be taken for granted.

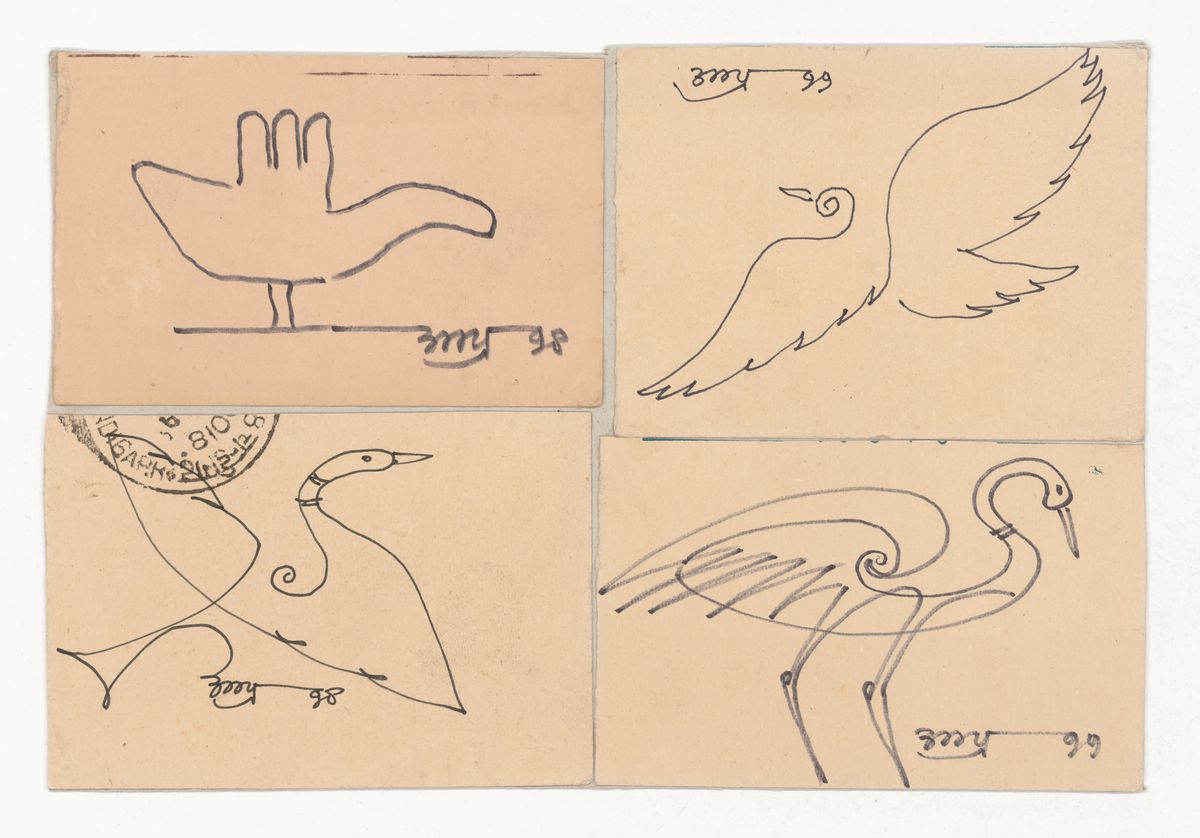

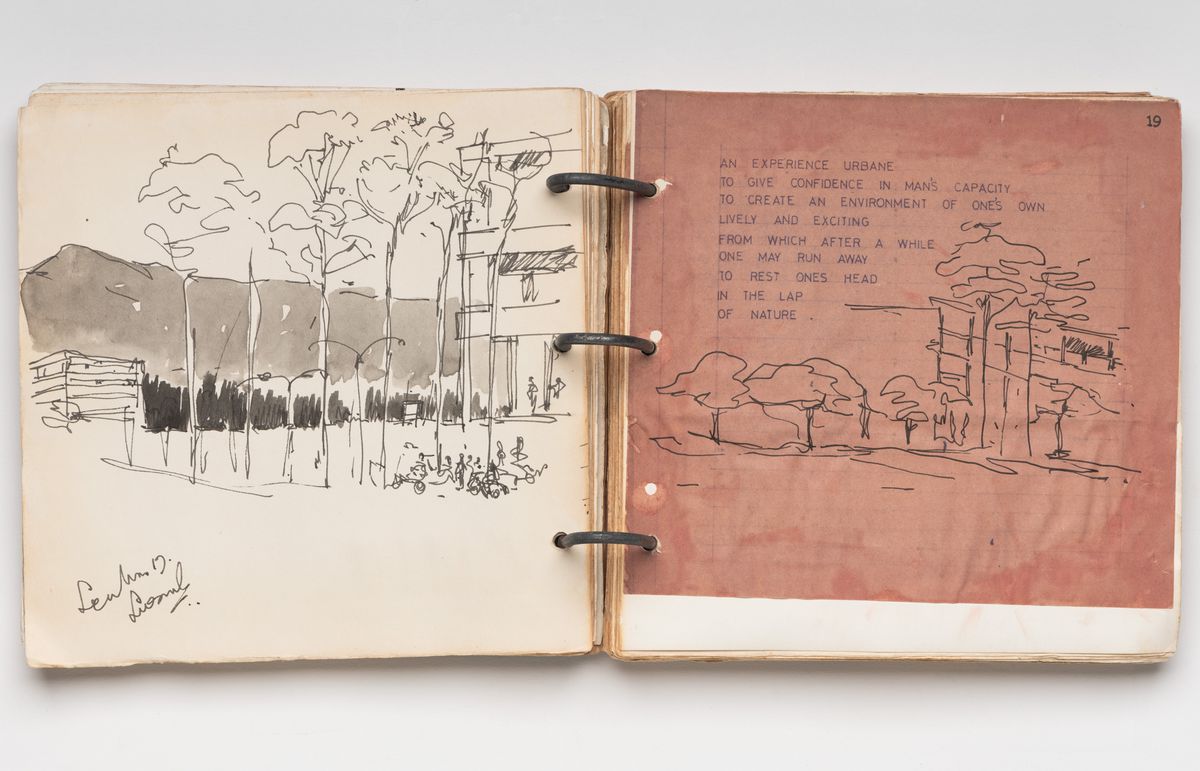

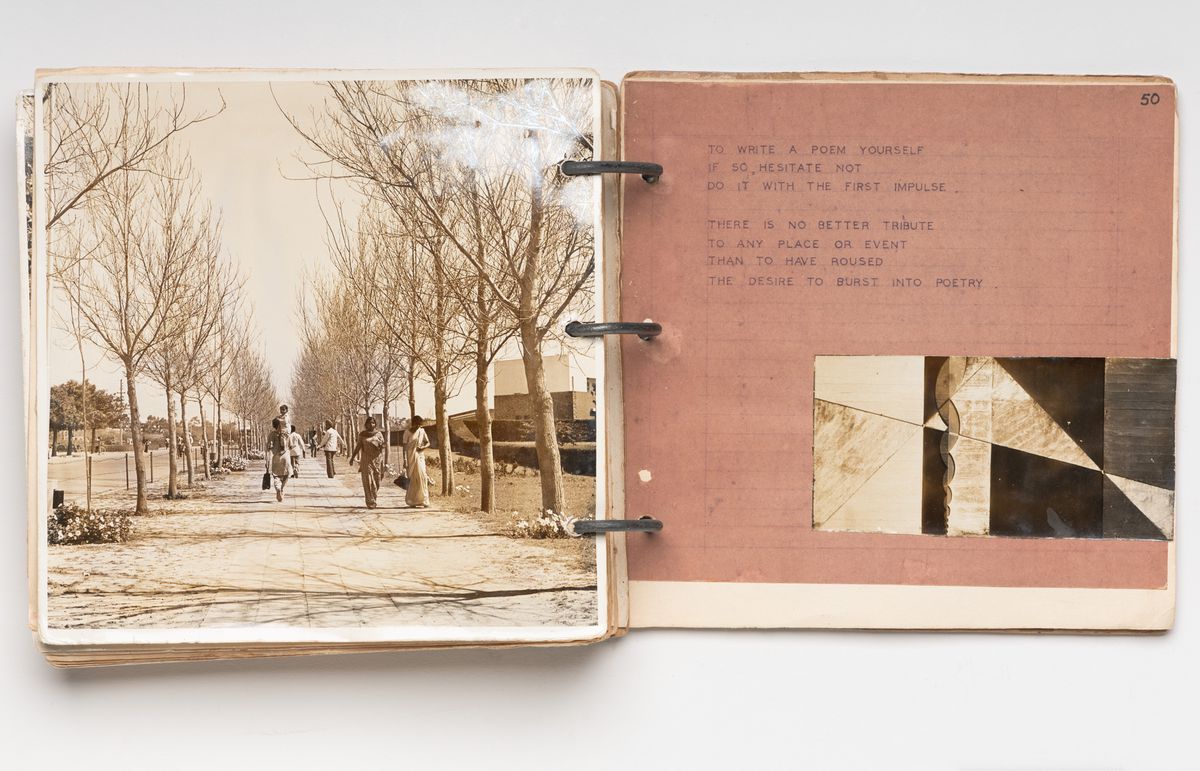

Conveniently for researchers, the Aditya Prakash fonds at the CCA exists alongside the Pierre Jeanneret fonds and the two archives are superb complements to one another. Jeanneret served as Chandigarh’s chief architect from 1952 to 1965 and his archive contains more extensive documentation about the Capitol Project than Prakash’s. This is because for Prakash, the building of Chandigarh marked the beginning of a journey rather than an end. Prakash’s archive reflects, by contrast, a longer intellectual odyssey spanning six decades of a relentlessly creative life. A painter, playwright, actor, photographer, designer, poet, researcher, and writer, Prakash was a man with seemingly inexhaustible creative energy. The materials in the archive span a range of unexpected and sometimes quirky forms, and include drawings, doodles, diaries, poetry, photographs, scrapbooks, letters, postcards, greeting cards, theatre scripts, and furniture and set designs, to name a few. Compellingly, the method of drawing with a single continuous line appears consistently throughout Prakash’s sketches and designs. This technique—which resonates metaphorically with the idea of intellectual activity sustained over the arc of a lifetime—thus became the title of Vikramaditya Prakash’s book about his father’s work, One Continuous Line: Art, Architecture, and Urbanism of Aditya Prakash. This book by the younger Prakash, an architect and architectural historian who has written extensively on the city of Chandigarh, provides an invaluable overview of his father’s activities, and is an indispensable resource for navigating the fonds.

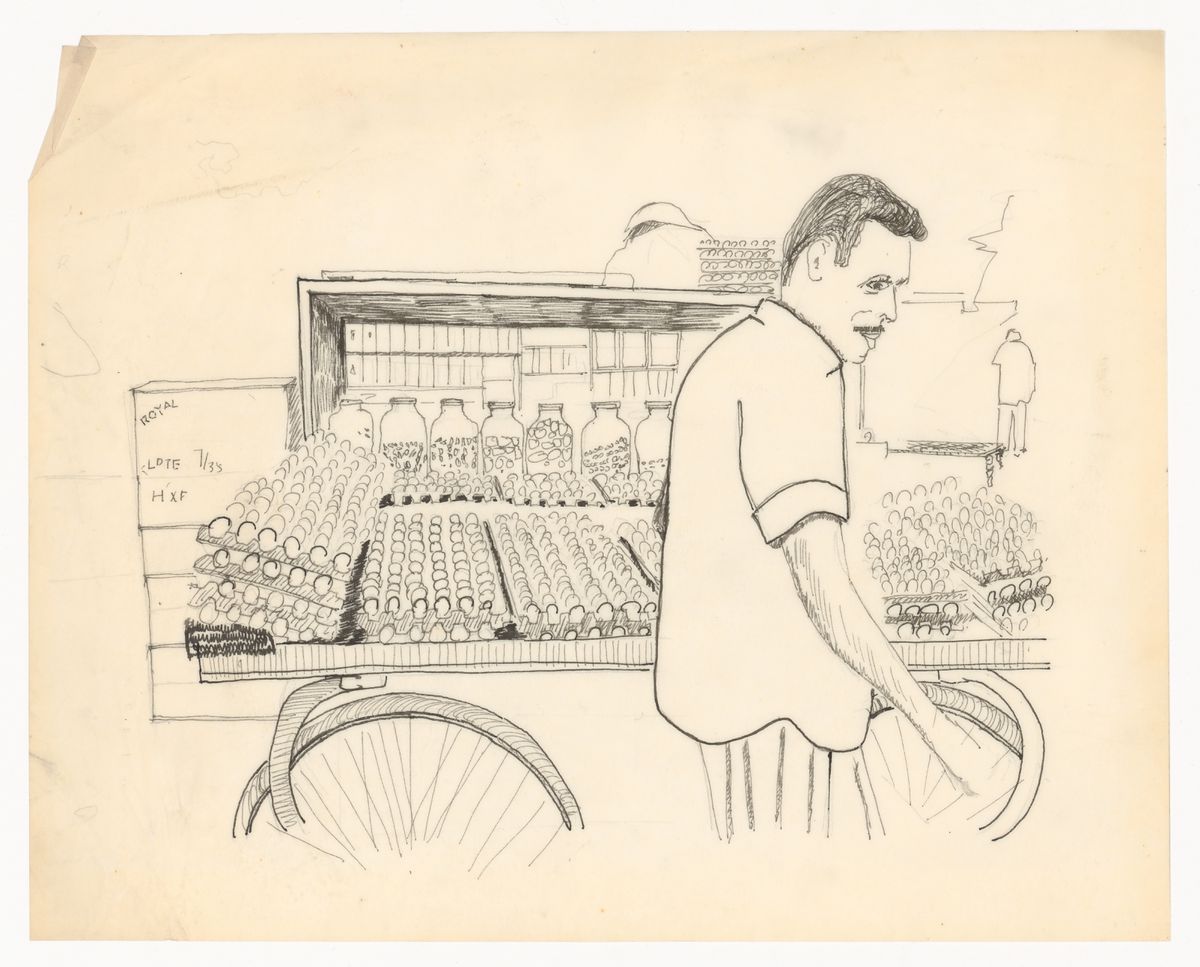

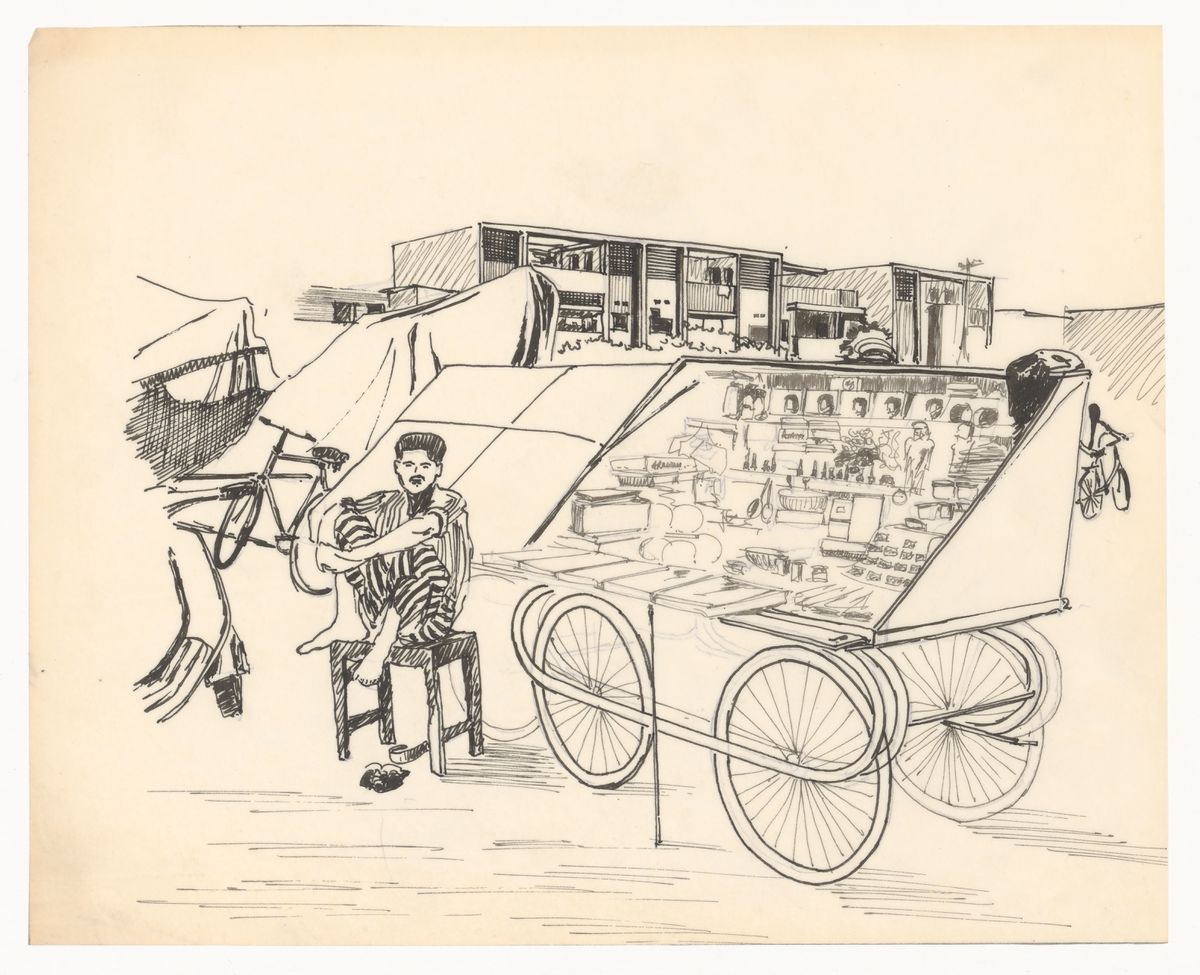

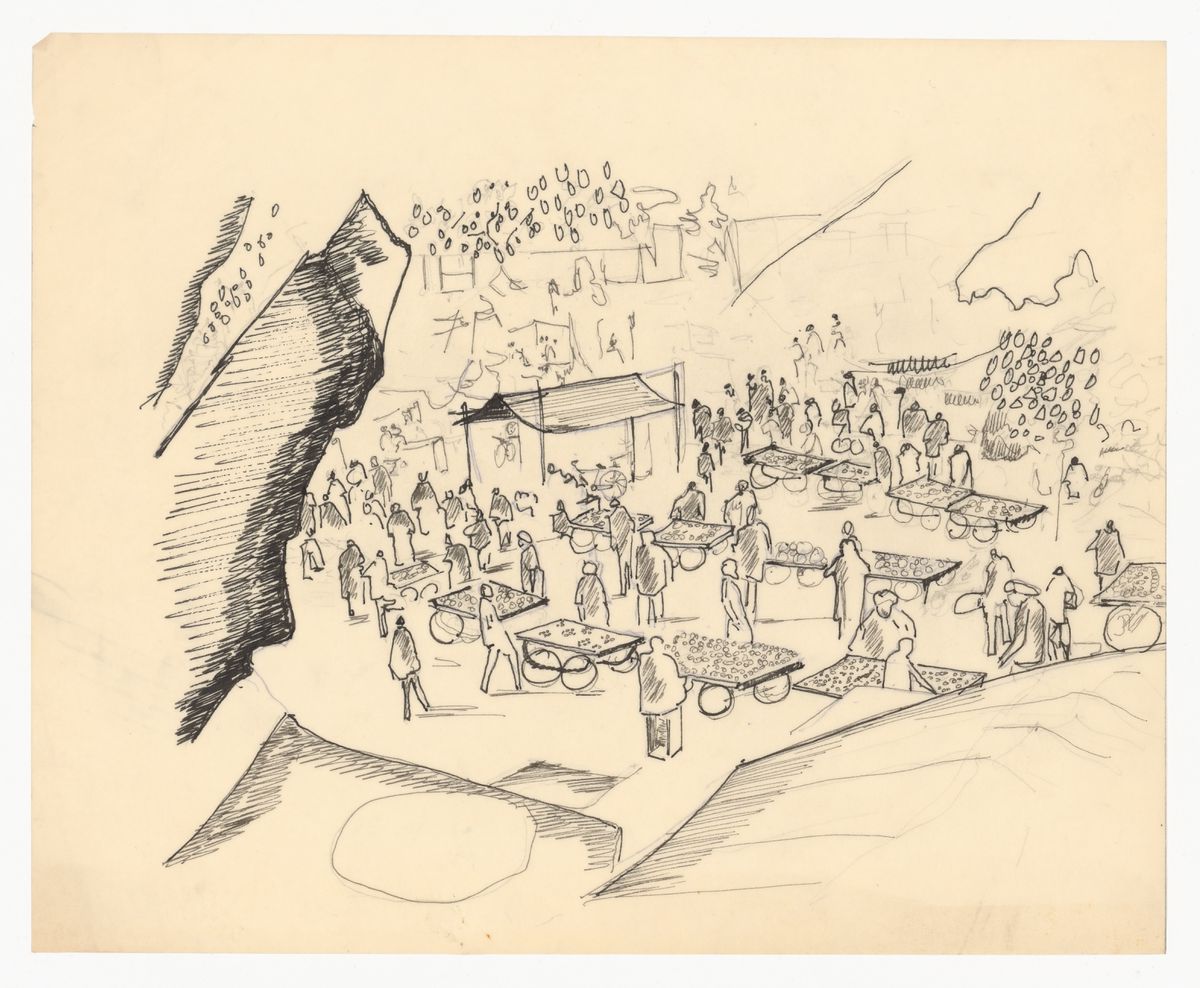

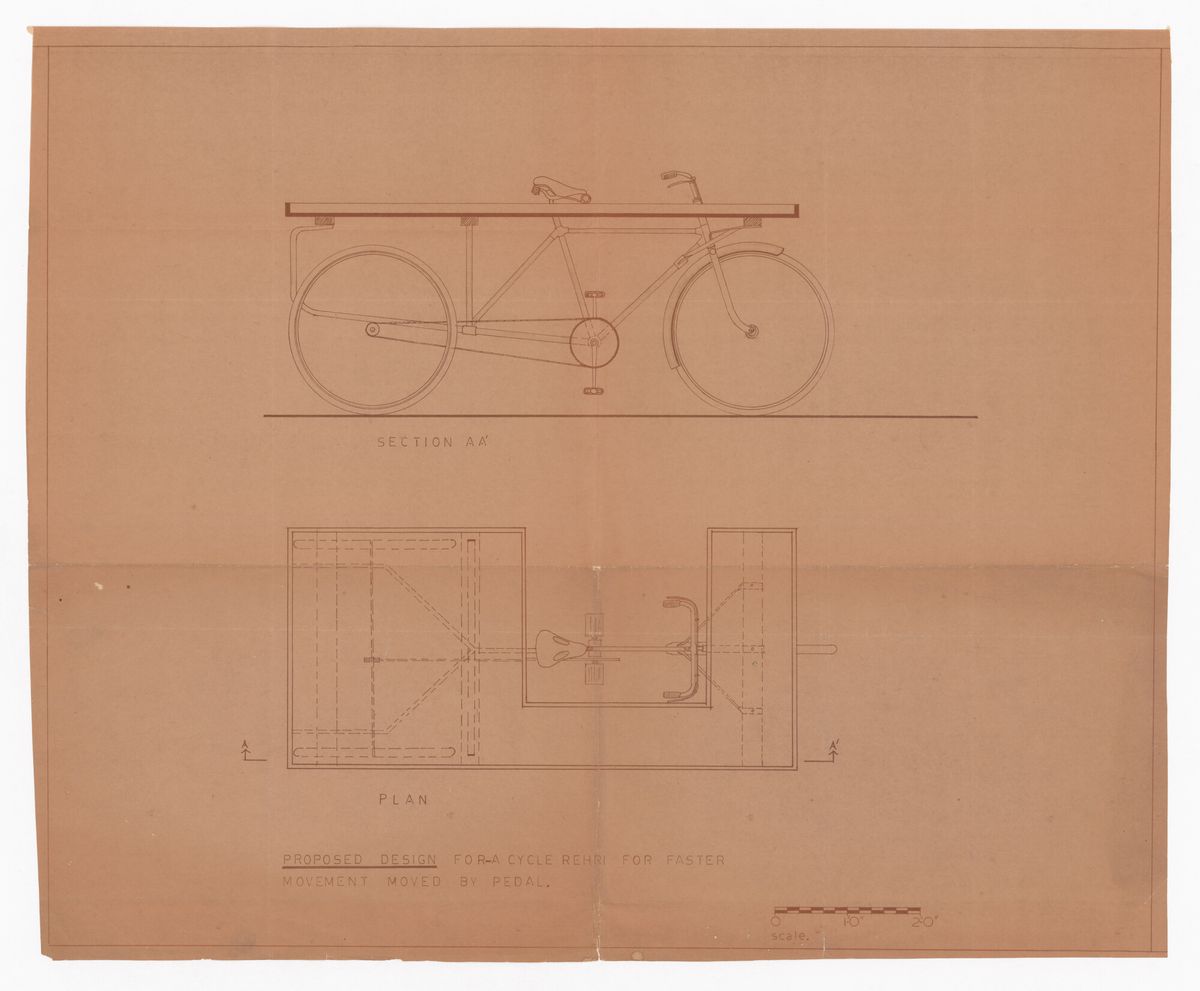

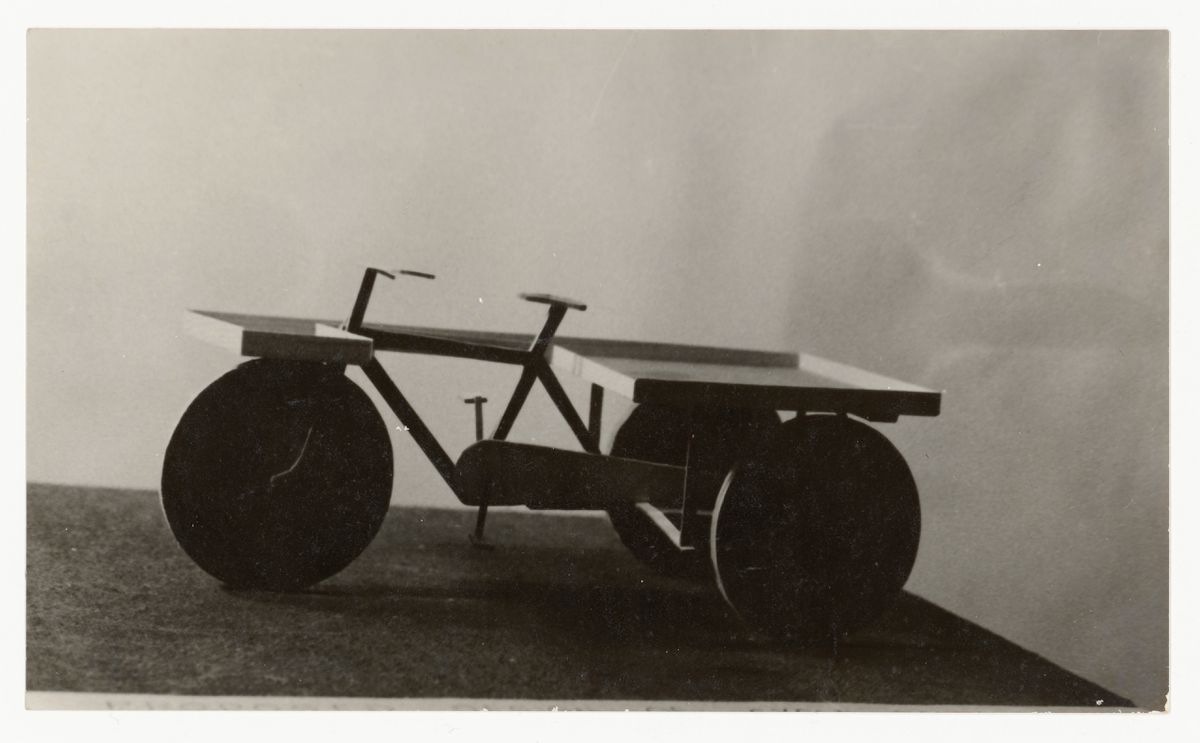

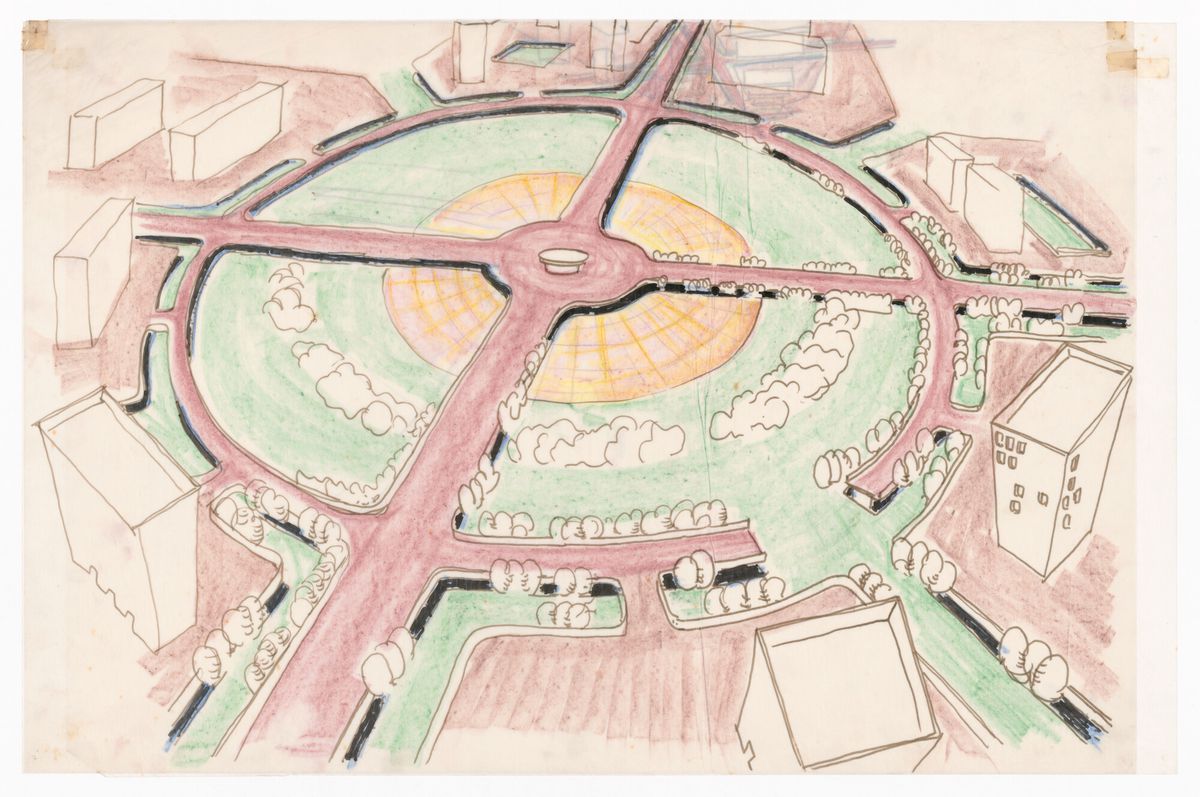

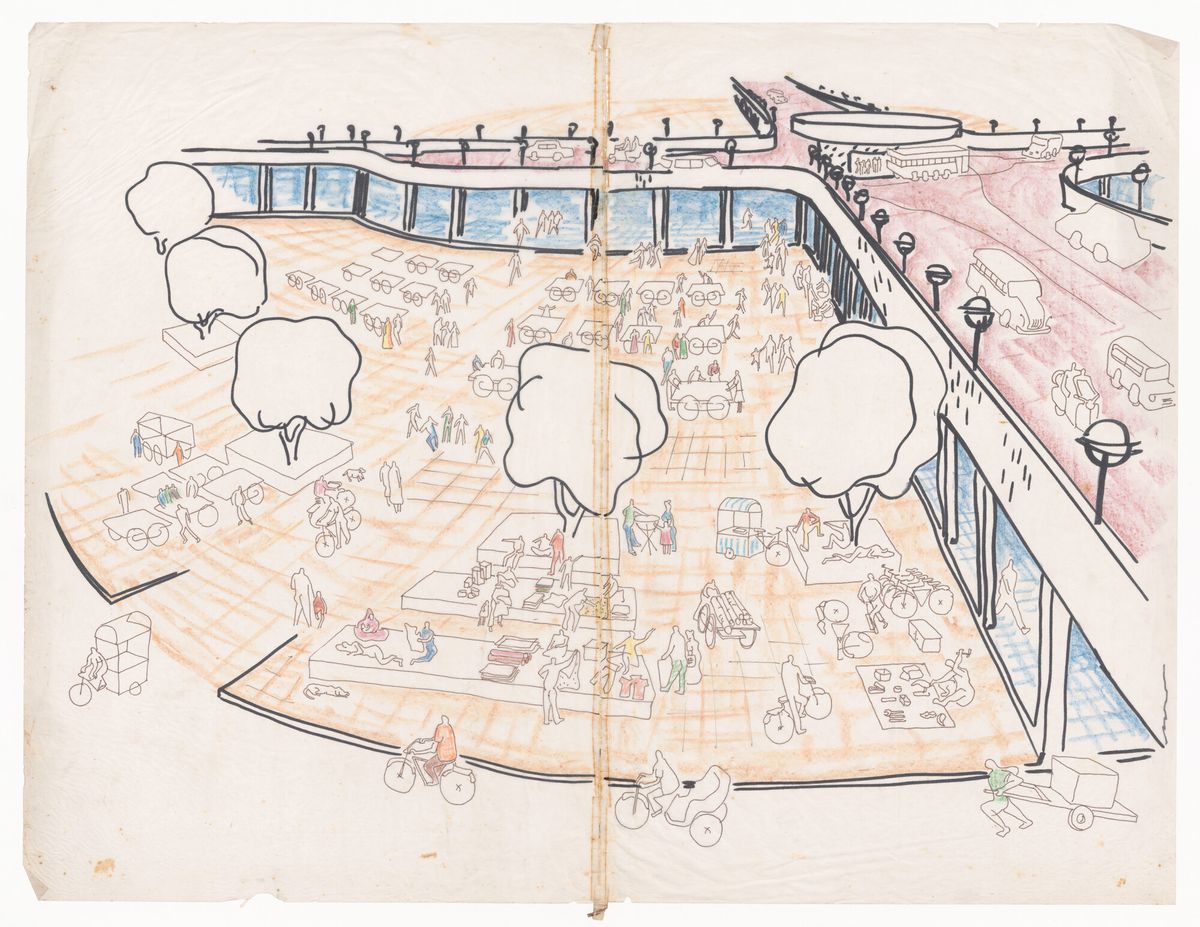

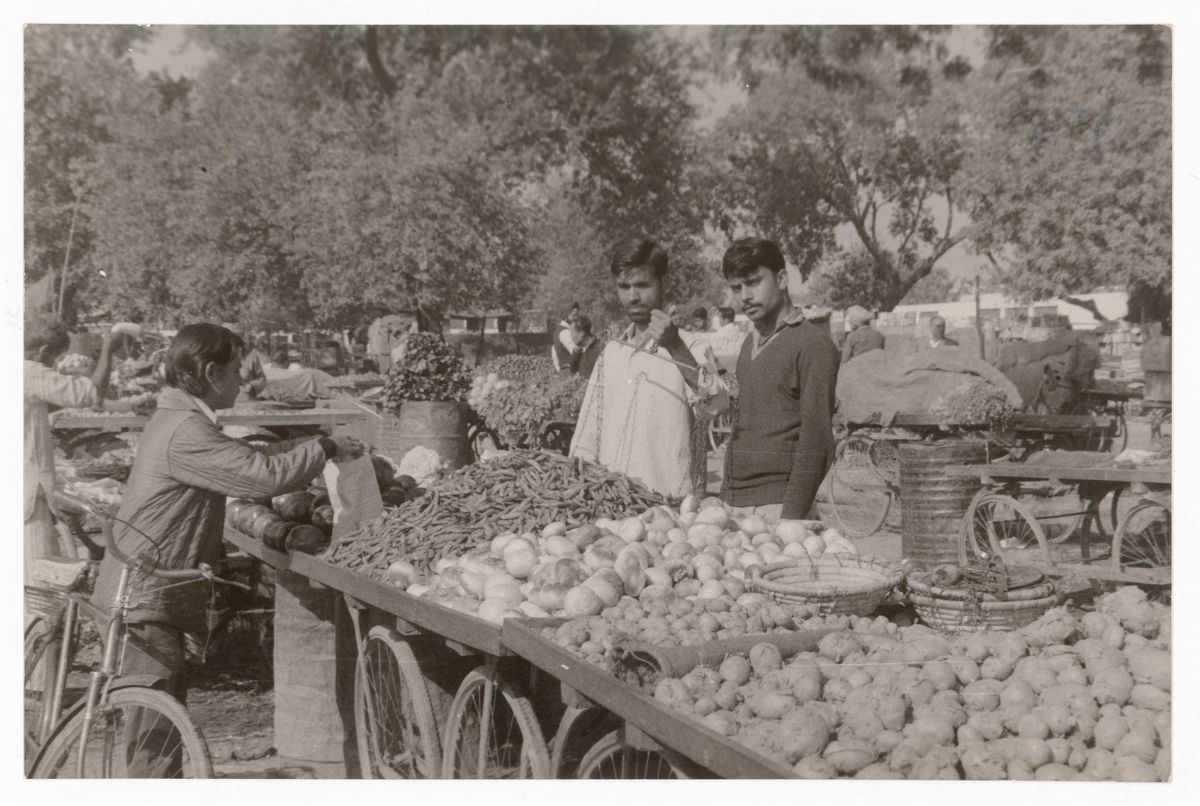

Aditya Prakash advocated for principles of planning that we now understand under the banner of “sustainability,” like recycling, integration of the informal economy, bringing agriculture and animals into urban spaces, and rigorously separating motorized and non-motorized traffic, which he referred to as “lethal” and “non-lethal” transport. Prakash took hundreds of photographs that dwell on this ecosystem, namely, the relentless interface of the village/urban relationship as it expressed itself throughout the region. Cattle, street-hawkers, squalor, and village-life are painstakingly recorded in these photos, but not because Prakash viewed these experiences as somehow at odds with modernist urban planning. Rather, he was interested in how such rural lifeways became enmeshed with urban design in India. Prakash’s ambitious conception of the Linear City, an urban model comprised of a uniform grid with elevated road networks, and his preoccupation with the rehri (the wooden cart belonging to a street vendor, or rehri-wallah), were both efforts to bring the so-called formal and informal spaces and economies into a single integrated urban vision.

Such an ecological vision of sustainable integration is equally present in Prakash’s paintings and drawings, especially from the 1990s on. By that time, he had retired from architecture and turned to painting full-time for the last eighteen years of his life. He had his first solo exhibition at the Taj Gallery in Bombay in 1989, just before a series of economic reforms in the 1990s would replace the socialist vision of the Nehruvian era, laying the groundwork for the globalized conditions we inhabit today. The exhibition featured twenty works depicting mythic forms from the organic world, mostly animals including birds in flight, bulls, swans, and peacocks. This naturalist subject matter was nonetheless calibrated through a distinctly modernist and geometric approach to line, form, and colour. “If the environment is healthy, delightful, and worth preserving then the value lies in discovering the form that fascinates,” he explained in his artist statement for the show. The goal was to “let the viewer feel that life is worth living in the lap of nature.” The archive contains correspondence from this final chapter of Prakash’s career with many luminaries from the Indian art world—including the legendary gallerist Kekoo Gandhy, the great dramatist, Ebrahim Alkazi, and major painters like Tyeb Mehta and Gieve Patel. Prakash’s life-long pursuit of a more harmonious relationship between our urban systems and the earth’s organic environment, sustained across his architectural, design, and artistic practice in different ways, prefigures a kind of ecological consciousness that is more urgent today than ever before.

As someone who was born in India and grew up in Canada (and has had a long career in the American university), I found it especially meaningful that the archive of Aditya Prakash has journeyed from India to find a new home at the CCA in Montréal. Although Prakash remained rooted in Chandigarh for his entire life’s work, the region of Punjab is no longer perceived to be as foreign, distant, isolated, or unknown as it perhaps once was to inhabitants beyond the Indian subcontinent. The powerful experience of global migration in recent decades has irreversibly brought the people and culture of Punjab to the rest of the world.1 It seems appropriate that Prakash’s life and legacy may now be positioned to give rise to new stories about national belonging, and is available to the next generation of researchers invested in such entanglements of the past, present, and future. In other words, the young man in the photo of the All India Radio broadcast appears destined to find new audiences and publics with whom to interact at the CCA. The Prakash fonds in Montréal reminds us that the history of modernism is a globally produced and intertwined story, and a shared inheritance that belongs to us all.

-

Today, the Punjabi population of Canada is over one million people, and the third most spoken language in the Canadian Parliament, after English and French, is Punjabi. ↩

Saloni Mathur’s residency was generously supported by Phantom Hands.

Related Residency