Heritage, Between Education and Practice

Nzinga B. Mboup identifies the value of Senegal’s architectural heritage with Jean-Augustin Carvalho, Fodé Diop, Andrée Diop-Depret, and Xavier Ricou

The second public event of the CCA c/o Dakar program, held on 17 August 2024, brought together four Senegalese architects whose work, both as students and in practice, stimulated a discussion about the definition and recognition of Senegal’s built heritage. While Xavier Ricou studied in Paris, graduating with a thesis project on Gorée Island, the other three architects graduated from the École d’Architecture et d’Urbanisme de Dakar (E.A.U.): Andrée Diop-Depret, was the first woman to graduate from the E.A.U. and her office GA2D has refurbished or renovated many historic monuments in Senegal; Jean-Augustin Carvalho, chose to work on the refurbishment of the Sandaga Market for his graduation project; and Fodé Diop, chose instead to work on the restructuring of the Island of Saint-Louis. Through sharing these diverse experiences, the public audience learned about strategies that can be adopted to identify and recognize the value of our heritage, learning from past successes and mistakes while shedding light on the challenges we are facing in the context of widespread destruction of the built heritage.

The importance of preserving the history and memory of a community or culture was a recurring topic during the discussion, reflecting a consensus regarding the need to acknowledge the history inscribed in the buildings that preceded our era, with a diversity of styles that manifests the endogenous cultures and the multiple exogenous influences that we have experienced.

The four architects who presented at the event developed their appreciation of heritage out of their family histories—as for Xavier Ricou with Gorée Island—or their life experiences—Fodé Diop went to secondary school in Saint-Louis. The courses at the E.A.U. also raised awareness of the built heritage among generations of students under the guidance of Professor Patrick Dujarric, travelling around Senegal and mapping the traditional architecture of various regions.

Listing heritage

“Not only does a Negro culture and civilisation exist, but they also assert their anteriority in relation to the culture and civilisation of the West, since they have, in more than one way, influenced, even conditioned, the culture and civilisation of the West, at least in their original form. So it is only right that Senegal should think about legally safeguarding—through classification, conservation and protection—monuments of a prehistoric, protohistoric and historical nature, dynamic witnesses of ancient times.”

“The aim is to learn more about our past, and to demonstrate the cultural, artistic and scientific development that has taken place in our country. We must make an inventory of all the elements that bear witness to our history and preserve them in the best possible conditions.”

Excerpts from the Loi sur les monuments historiques (Historic Monuments Bill) of 13 April 19711

-

See https://www.dri.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/LOI/1971/Commission-loi-decentralisation-et-travail/LOI-N-71-12-DU-06-AVRIL-1971.pdf. Original French text: “Non seulement une culture et une civilisation nègres existent, mais encore, elles affirment leur antériorité par rapport à la culture et à la civilisation de l’Occident, puisqu’elles ont, par plus d’un côté, influencé, voire conditionné, la culture et la civilisation de l’Occident, du moins dans ce que celles-ci ont d’originel. Aussi n’est-il que très légitime qu’au Sénégal l’on pense à sauvegarder juridiquement, par la classification, la conservation et la protection, les monuments à caractère préhistorique, protohistorique et historique, témoins dynamiques des temps anciens.” “Il s’agit de mieux connaître notre passé, d’apporter chaque fois la preuve du développement culturel, artistique et scientifique dont notre pays a été le théâtre. Il faut recenser tous les éléments témoins de notre histoire, les conserver dans les conditions les meilleures.” ↩

When the law was enacted, only Gorée Island and Cap Manuel were subject to legal protection. Today, the list of historic monuments in Senegal has grown to include hundreds of sites throughout the country.1

In order to understand the value of built heritage and protect it, we first need to list it, study it, and identify its features. This is what Xavier Ricou and Fodé Diop did for the islands of Gorée and Saint-Louis, respectively, with their graduation projects. They described and analyzed their geographical contexts, the urban morphology, the building types, and above all the living configurations and the technical elements (materials, types of roofing, balconies) that define the architecture of these islands. The poor state of conservation of the buildings was also a central concern in their mappings, proposing technical solutions to improve it such as the treatment of capillary damp.

Although these graduation projects were theoretical and not intended for practical application, they bore fruit in Ricou and Diop’s careers, which were largely focused on protecting the islands. Diop chose the subject of his thesis thinking about its “usefulness” or applicability, and in 2000, he was able to revisit it and update it to serve as a basis for the classification of the Island of Saint-Louis as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Xavier Ricou then took on the task of setting up the conservation plan.

Jean-Augustin Carvalho turned to more recent forms of heritage for his graduation project, namely the Sandaga market. The building, with its Sudanese-Sahelian architecture1 dating from the 1930s, was still one of Dakar’s leading commercial hubs during his studies in the 1980s, but had already been swallowed up by a proliferation of stalls spreading into the surrounding streets. Carvalho’s project focused not on the building itself, but on its function as a market in Dakar and the expansion of its functions across the urban block. The analysis of the different programs, the foodstuffs and objects sold, the layout of the stalls, and the spatio-temporal flows informed the restructuring proposal for the alleys emanating from Sandaga to form a new shopping centre. This research project was supported by the Dakar City Council, to whom Carvalho offered the project to serve as a basis for the discussions about the future of a market that was seen as embodying the soul of Dakar.

-

The Sudanese-Sahelian style, coined by President Senghor in reference to French Sudan—the French colonial denomination of what became the state of Mali, with which Senegal formed a federation—and the larger African context. The building’s architecture anchored the building in its urban environment. ↩

In 2013, the market was tragically damaged in a fire and subsequently demolished in 2021. This fuelled a new debate on the value and preservation of heritage, and led to legal battles, technical studies, and designs. An unrealized project by Andrée Diop-Depret and her firm GA2D aimed to restore the building’s original envelope and functions by reinforcing the structural elements damaged by the fire. One of the functions that Diop-Depret wanted to restore, long forgotten by young people in Dakar, was the market terrace, which had hosted balls and rehearsals by dancers from the Daniel Soprano theatre, and could have been used for other cultural events in the city.

The contributions of the four architects at the discussion highlighted a cross-disciplinary understanding of the historical, socio-cultural, material, and urban considerations of the built heritage, based on research, cataloguing, and mapping that not only seek the preservation of the buildings but also bringing them to life in the contemporary context.

Preserving architectural heritage

In addition to the unfinished Sandaga market project, Andrée Diop-Depret presented a number of restoration, refurbishment, and renovation projects for listed buildings designed by GA2D over the years.1 The implementation strategy for these projects is based on knowledge of history, materials, and construction processes, echoing the research and mapping work of Xavier Ricou.

-

Andrée Diop-Depret elucidated the distinction between these three terms. Restoration involves restoring the building to its original state, strictly. Here again, the aim is to preserve the building’s historical heritage, even more strictly than in the case of renovation. Refurbishment consists of redeveloping a building while preserving its exterior appearance and improving its interior comfort. Thus, refurbishment presupposes respect for the architectural character of the buildings. Renovation can lead to a change of use for the building. The aim of renovation is to make the building as good as new. ↩

“The built heritage has continued to deteriorate. The building materials are ageing prematurely and the lack of maintenance means that even old walls end up collapsing. There’s also a loss of know-how, which means that when an old wall is repaired, it’s done in the style of the twentieth or twenty-first century, and not the way it used to be done in the past, with layers of stone one on top of the other.” Xavier Ricou

“In Gorée, the lintels were made of wood and to support the lintel, to give it a little more strength to hold the balconies, stone arches were put up, made of bricks… These arches were found on the gallery and restored. The plinths and posts were also made using the same system of basalt rubble bonded with lime.” Andrée Diop-Depret

The restoration projects by Diop-Depret / GA2D and Ricou for the Maison des Esclaves (House of Slaves) and the Maison Victoria Albis in Gorée began with surveys that made an inventory of the modifications made to the buildings over time. The analysis also made it possible to study the composition of the walls made of basalt rubble assembled with lime and shell mortar, to which cement-block walls were added in the twentieth century. The restoration preserved the visual aspect of the buildings on several fronts: On the façades, arrow slits and blocked windows were identified and brought back to their original state. To keep with the materiality of the buildings and the site, GA2D sourced stones from Popenguine to restore the steps of the central staircase.

“At the Maison des Esclaves, all the galleries were lined with wood, with beams made of palmyra palm… These palms can’t be cut anymore in Senegal, but we managed to obtain a special permit to allow the company to do it so that we could replace certain elements.” Andrée Diop-Depret

For the renovation and extension project of the Dakar railway station, GA2D’s approach was to retain the terracotta brick façade and the original metal structure, while reorganizing the interior spaces to meet the needs of the new regional express train (TER). The metal structure was reinforced by a parallel reinforced concrete structure on the inside, and the attic space was used as a technical area for the new mechanical ventilation system. The floors were redone using the traditional granito or terrazzo technique, using marble from the Kédougou region in eastern Senegal. The ceramics on the main facade were redone in collaboration with Dakar ceramist Mauro Petroni, to match the originals. The metal and brick extension extends the original station’s palette of materials, making this renovation an example of how an old infrastructure can be updated to serve the country’s current and future needs. These projects by GA2D demonstrate how the architect’s knowledge of history, materials, and techniques is crucial to the enhancement of heritage, so as to preserve infrastructure and memory while bringing old buildings into the present with contemporary functions.

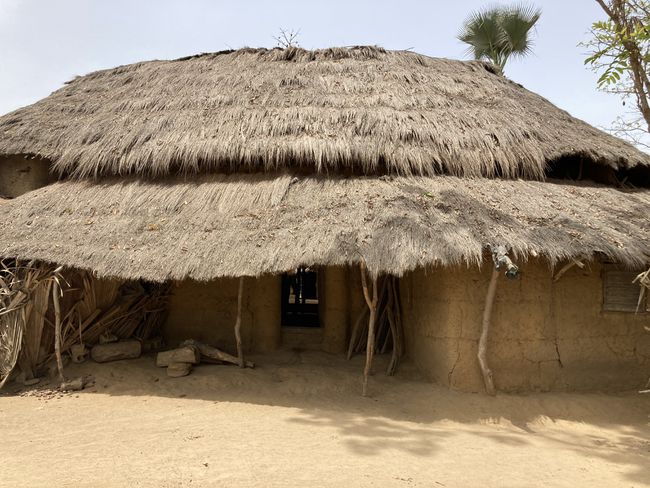

Traditional built heritage can also inspire architects in their contemporary designs, as in the case of the Saint-Maur market in Ziguinchor. This project enabled architect Jean-Augustin Carvalho to pursue his interest in the central function of markets by drawing inspiration from traditional Diola architecture, in particular the impluvium huts, organized around a central atrium that brings light into all the spaces.

What tools and challenges?

Traditional architecture offers a wealth of lessons on passive strategies for thermal comfort, as well as on the use of local resources to construct buildings rooted in their context. The Casamance impluvium hut, for example, embodies the principles of natural lighting, rainwater collection with naturally ventilated thatched roofs, and the constructive know-how of earthen walls. The colonial period saw the introduction of construction techniques using basalt or limestone (Rufisque stone) and, later on, the use of terracotta buildings, which are characteristic of Saint-Louis. Even after independence, the modernist architects of the 1970s, such as BEHC (Bureau d’Études Henri Chomette) and Birahim Niang with ADAUA (Association for the Development of Traditional African Urbanism and Architecture) in the 1980s, also adopted a natural architectural approach, using locally-produced terracotta.

The conservation of built heritage relies on specific know-how: knowledge of materials and construction techniques other than reinforced concrete, concrete blocks, glass, or aluminium, materials that dominate the current construction industry in Senegal. The loss of knowledge is impoverishing architectural culture and the built environment, which is increasingly dependent on imported materials (tiles, steel, and aluminium), and existing buildings are becoming more and more difficult to renovate or restore.

“We made recommendations for the creation of a heritage training centre in Saint-Louis, which would enable people to relearn the skills involved in safeguarding and refurbishing heritage.... To push the building codes and Senegalese authorities to invest in a manufacturing unit for roof tiles, clay bricks, etc. so that the components used in the restoration of heritage buildings could be produced on site, with a training centre next door that could use these components (joinery, carpentry, and all that) to make the work on the ground more effective.” Fodé Diop

The importance of transmitting knowledge about built heritage and the places where this knowledge is passed on is a social endeavour that will enable us to take a critical look at our history while equipping us with the tools to enhance our different cultures and develop our economy. This foundational knowledge is necessary if we are to make informed choices about the transformation or preservation of our heritage, and if we are to serve the interests of our societies today. Forgetting is certainly a strategy that allows us to demolish and rebuild, at the cost of losing heritage wealth, natural resources, and ancestral know-how in favour of political and industrial interests seeking to gain a monopoly on markets.