Drawing Closer to Nature

Yu Momoeda on the Shoei Yoh fonds

I started studying architecture in Kyushu, Japan. In the beginning, I distinctly remember being amazed at the level of conceptual abstraction in Shoei Yoh’s works while leafing through the pages of a magazine. Later on, I had the chance to see some of his projects, most of which are located in Oguni-machi, Kumamoto Prefecture, with the rest scattered across Kyushu. I was moved by the tangibility of the materials, detail, and structure of his creations. Then last year, I had the opportunity to meet and talk with Yoh for the first time. And now, the CCA had requested my services as a respondent in the capacity of a designer, a fledgling architect, who has been influenced by Yoh’s architecture. I would like to take this opportunity to note and reveal the enormous amount of passion—supported by an equally enormous amount of archival materials—that Yoh infused into design.

Yoh began his career in interior and product design. He eventually transitioned to designing public facilities such as houses, gymnasiums, and community centres. His output evolved from cubic, interior-like objects to architectural spaces that blend perfectly into their surrounding environments. As he shifted to designing buildings, Yoh started to favour free and open spaces that drew closer to nature, harmoniously combining diverse materials such as glass and bamboo. Yoh gave the name “elastic architecture” to his architectural works of this period, and the CCA holds a selection of these projects. Through the volume and diversity of the archival holdings—sketches, model photographs, completed drawings, and more—I could deeply feel the urgent drive with which the firm Shoei Yoh + Architects pursued “elastic architecture”.

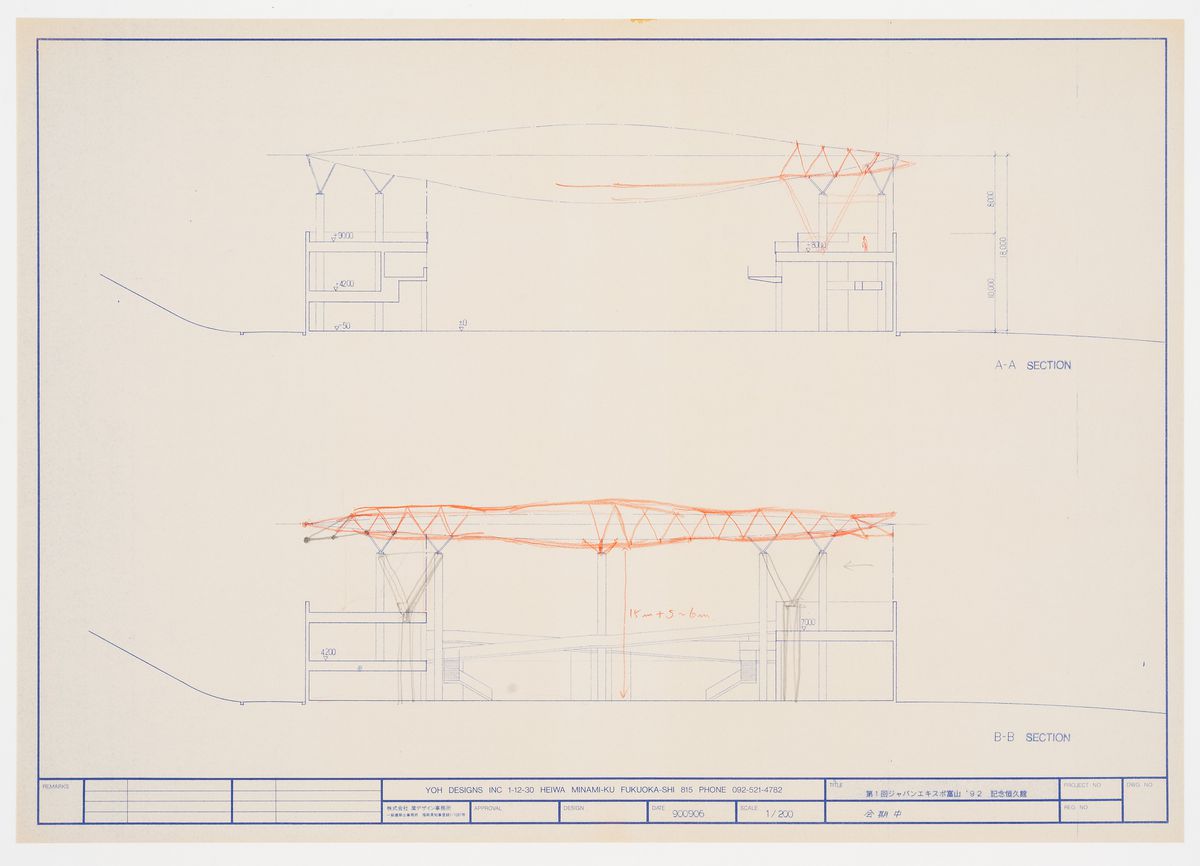

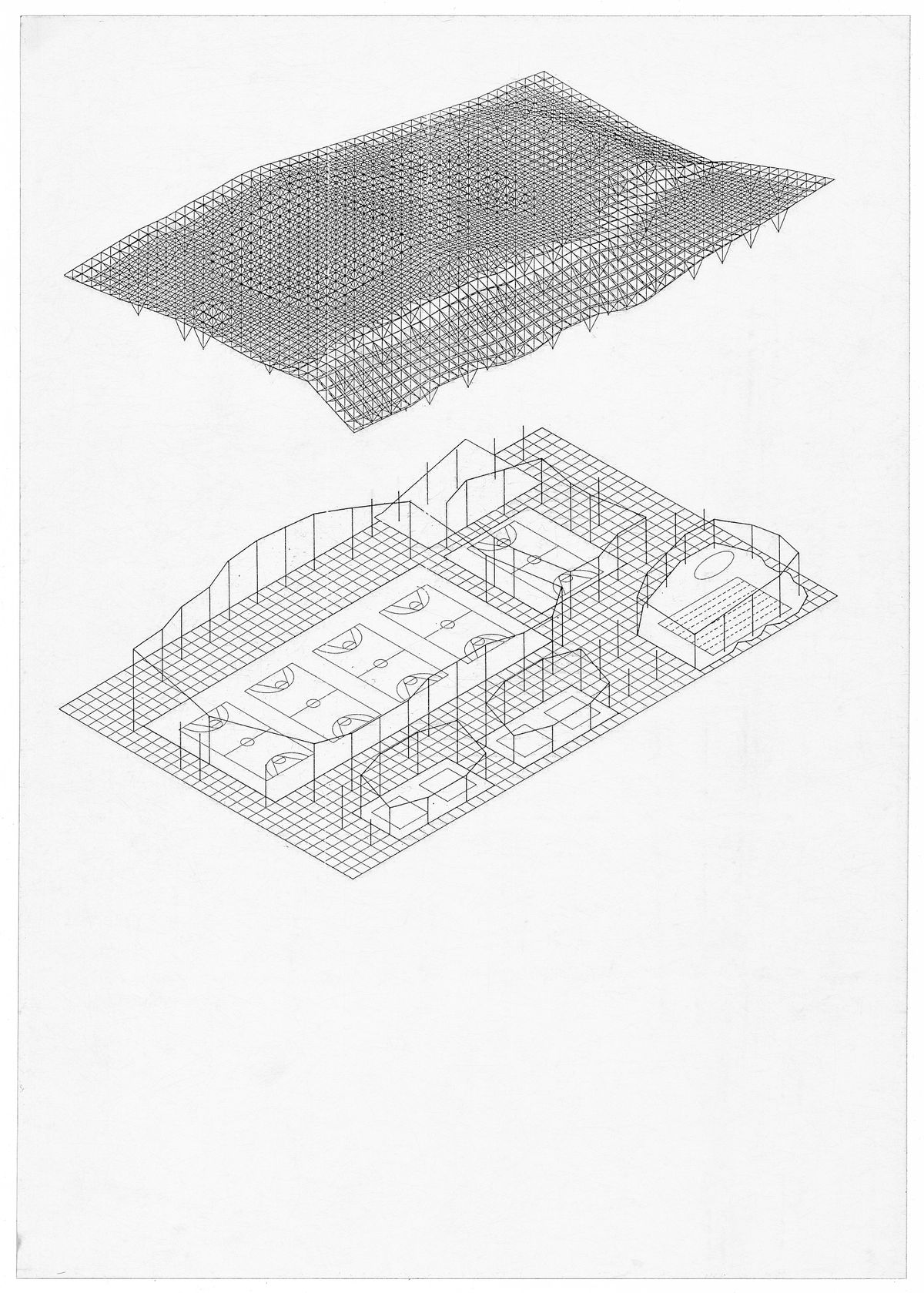

Galaxy Toyama’s distinctive free-form roof was designed to be an optimized structural solution. It was inspired by and developed using a photoelasticity stress analysis technique introduced by the structural engineer Gengo Matsui, who also collaborated with Yoh on his Oguni-machi Dome project. Galaxy Toyama features a complex double-curved surface that was functionally designed to accommodate snow accumulation.

In the fonds, an A3 binder contains stress analysis drawings and photographs of a contour model made with mesh material. Framing documents feature a great number of figures that crowd an axonometric roof to indicate thicknesses at different points. These drawings were done by hand following the results of a computer analysis.

Moreover, the built model played a crucial role in providing a physical representation of the stress analysis. Yoh once mentioned that he was literally awestruck by the approximation of streaky shadows juxtaposed by photoelasticity patterns projected by the model. The excitement he felt can be sensed as you leaf through the many pages of images that capture the roof casting shadows from different angles.

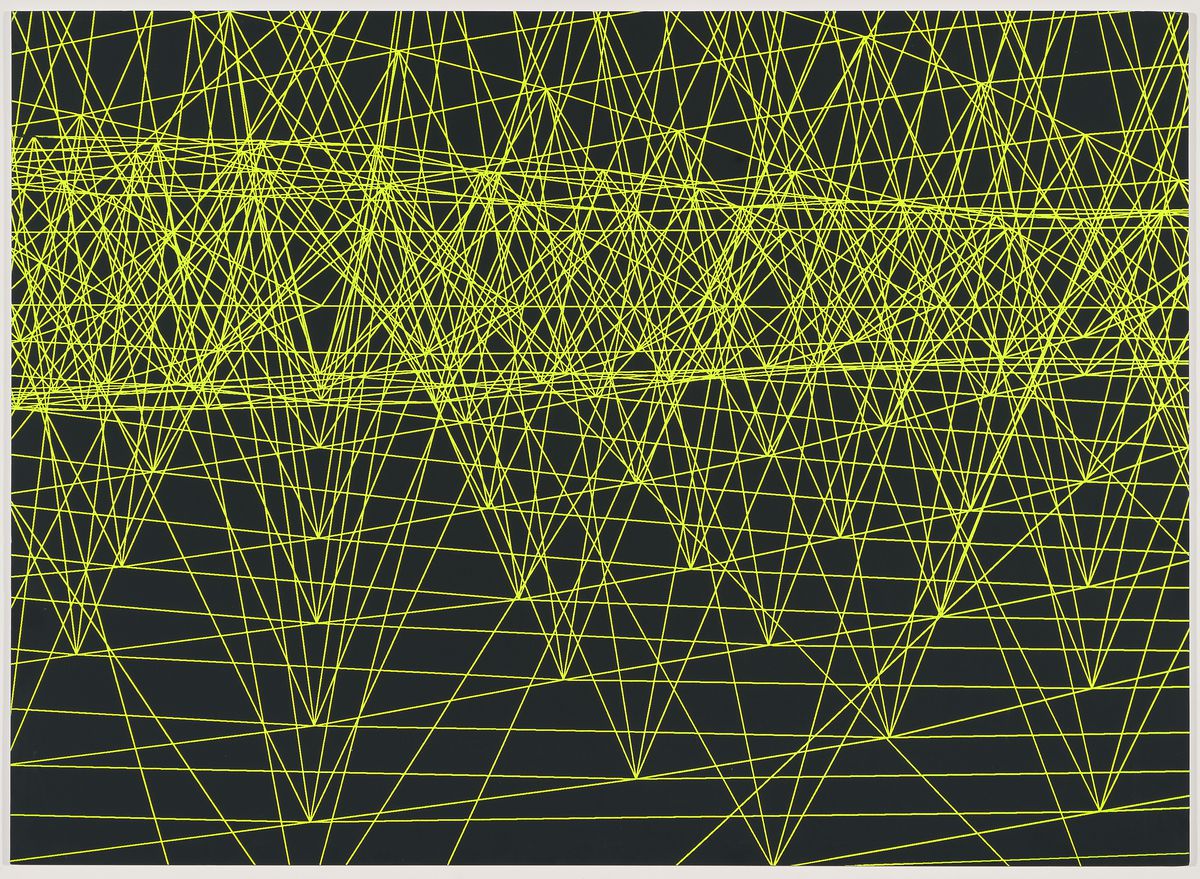

The perspective upward, from within the space of the roof, motivated the title of the project: Galaxy. The space immediately under the roof is not meant to be one that can be inhabited. However, Yoh designed it as a geometrical realm that would evoke the Milky Way while still prioritizing the structural rationality of the roof. He had printed out a large number of perspectives and, now, these images in the archive suggest that the modelling served as a tool to understand not only the design but also the experiential quality of the space. They yield clues to the approach that firm Shoei Yoh + Architects took to create an unprecedented panorama during the early 1990s.

Prospecta Toyama is an outline of a cube, thickened in concrete, that generates fog and functions as a viewing platform to observe the fog itself. Among the archived sketches is an intriguing collage titled “A cube floating in space.” It seems that the fog-generating frame had been conceived to represent a ship floating in space. Like Galaxy Toyama, the spaces imagined by Yoh go beyond earthly settings to reach out to the cosmos.

Prospecta Toyama also alludes to a magnetism. Through architecture, Yoh tried to capture natural phenomena such as magnetic fields, fog, and rainbows, which are all the result of the movement of the Earth through the universe. While Prospecta Toyama is a device that generates fog within the water-rich environment of Toyama Prefecture, it is also a representation of the relationships through which the Earth generates various natural phenomena within the cosmos.

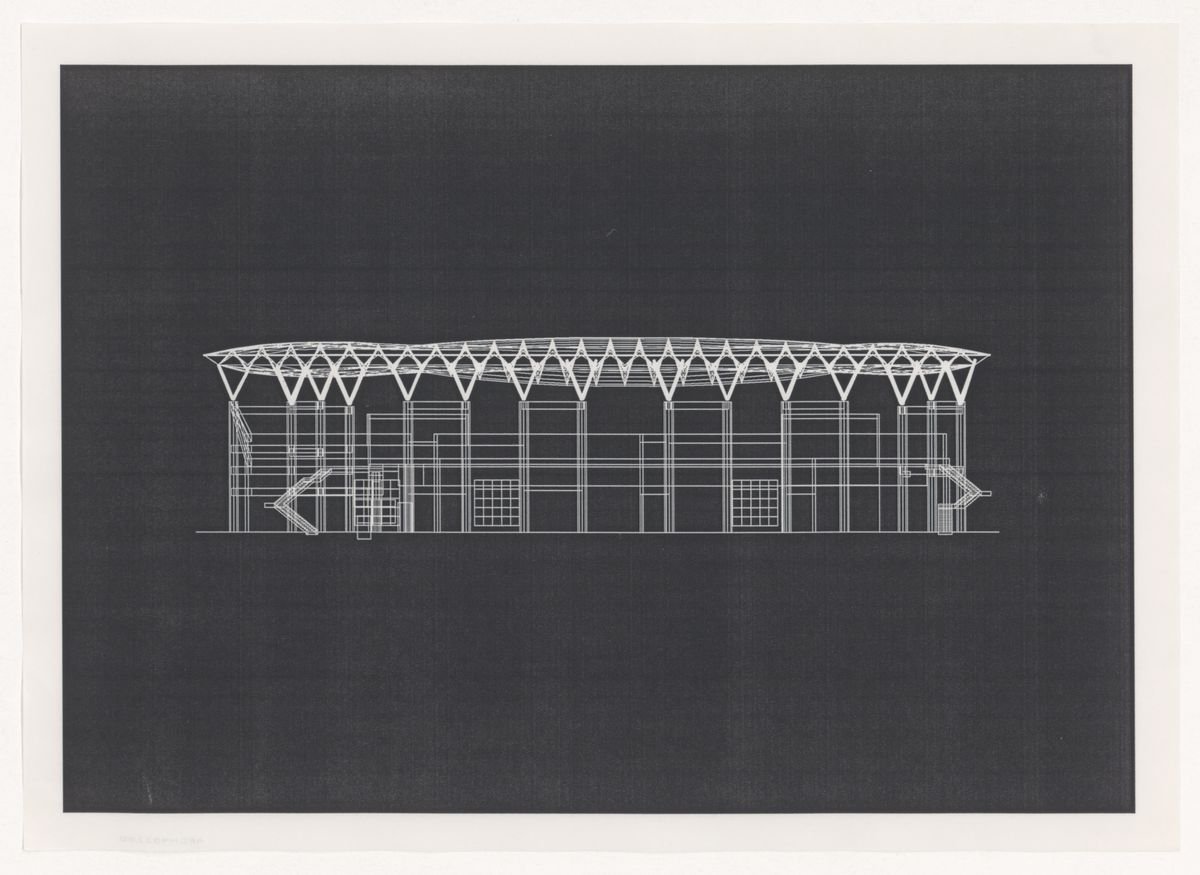

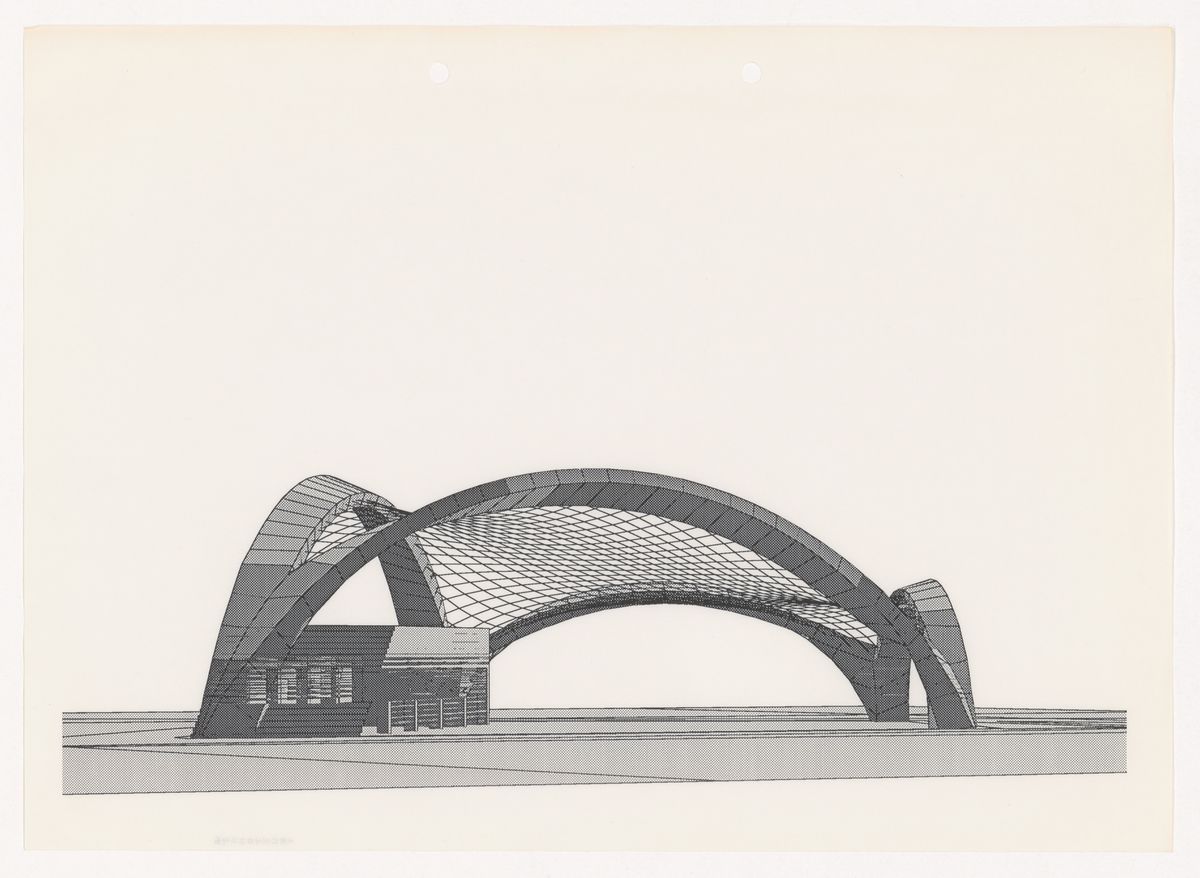

The Odawara Municipal Sports Complex is a competition proposal based on the roof design of Galaxy Toyama. This structure did away with the horizontal line that runs through the centre of the arch on Galaxy Toyama’s roof. Furthermore, in order to create a natural-looking design, a diagonal cut slices through the semi-cylindrical roof structure, giving it a curved edge.

A diagram of the curved cross-section found in the archived presentation materials looks as if it were an earthworm or a brushstroke of a calligrapher. The whole structure of the gently curved roof is supported by a truss-like column. At the time of its construction, the Odawara Municipal Sports Complex offered a form that differed from anything seen until then yet still blended seamlessly with nature.

The Glass Station, located in Oguni, Kumamoto Prefecture, consists of a bold concrete structure made of keel arches and a fireproof glass membrane roof that fills the spaces between the framework. The offices of Harada Concrete Co. (also designed by Shoei Yoh + Architects), the client who commissioned the design of Glass Station, are across the street so that together with the surrounding natural landscape, the two structures serve as a gateway to the town of Oguni. Structural analyses in the fond show that, with this design too, the shape of the free-form roof surface is structurally optimized. The roof framing plans show many handwritten figures indicating heights at different points of the glass surface, which were coloured in using a light-blue coloured pencil, making for a set of utterly captivating and organic drawings.

The archive materials also feature photographs that record the different stages of the Glass Station’s construction. It is impressive to see how concrete was poured into a curved wooden formwork to build the structure over twenty years ago. When I was a university student in 2004, I had a part-time job making models at the construction site of Gurin Gurin, designed by Toyo Ito & Associates. It was a chance for me to see first-hand how difficult it is to build free-form concrete structures. It is incredible that, more than a decade prior, a small design office managed to band together with a local contractor to accomplish this difficult task in the countryside of Kyushu.

Reading some of the faxes that were exchanged between the architectural firm and the collaborators about various design and construction processes was a most thrilling experience. I also found sketches showing an inversion of window organization as a strategy to increase rigidity over the facade surface. All these records make it possible to imagine how a large team of experts—a construction office, membrane manufacturer, builders with advanced concrete waterproofing techniques, glass construction specialists—collaborated to erect the Glass Station.

The Naiju Community Center resembles a handkerchief placed over a tall object, much like Shiro Kuramata’s K-SERIES lamps, which Yoh himself once declared had been an influence on him. During an interview with the design staff around the time the structure was built, it was mentioned that Yoh himself had probably come up with the idea after seeing how freely a grid of woven bamboo sticks could be manipulated. The structure is paired with concrete to reinforce its structural integrity and create a single three-dimensional object. Yoh appeared to have been more interested in this process than in its resulting shape.

Since Yoh began his career designing products and interior spaces, it seems fitting to consider the connection between his characteristically bold structures and smaller-scale products such as lamps. In recent years, some of the three-dimensional forms most often used by architectural design firms include elements inspired by existing popular industrial design creations. Yoh’s concrete-shelled bamboo “handkerchief,” which came to life some twenty years after Kuramata’s K-SERIES lamps, is a testimony to the differences between the product and the architectural structure made all the more apparent by the significant gap between the techniques and time required to craft each. Once the concrete had been poured into a crane-suspended bamboo formwork, a great number of iron reinforcing bars were inserted into the amorphous concrete surface to enable the structure’s appearance—as if it were floating against gravity.

Just like the Naiju Community Center, the Uchino Community Center for Seniors and Children in Chikuho, Fukuoka Prefecture, features a roof built using a bamboo formwork covered by a concrete shell. Made from locally grown bamboo, the ceiling formwork was left in place after the concrete had set, giving the enclosed community centre and nursery a warm finish.

Yoh believed that any architectural undertaking should be carried out in a reasonable and economical manner. He could come up with such original designs because he considered the whole process—including the finishing details—from scratch.

A detail drawing of the stainless-steel drainpipes shows that, to make the roof look thinner and ensure proper rainwater flow, thorough consideration was given to the grade at every cross-sectional point of the free-form roof. The seamless integration of requisite features with the curved plane creates a most natural-looking roof. In order to accomplish such a feat, the whole project staff collaborated to experiment with materials and to plot information onto drawings. Tools such as 3D printers did not yet exist. Architectural work was still the result of linking the digital (data) with the analogue (materials).

Interacting with Nature through Parametric Thinking

The records contain few sketches drawn by Yoh himself. A possible explanation could be that he may have favoured a parametric approach to architecture, that is, he worked by setting parameters and establishing links between actions. Architectural forms were determined by incorporating local materials and conditions as constraints: for instance, Yoh used forest-thinning timber for the Oguni Dome, took snow load into consideration when designing Galaxy Toyama, and used locally grown bamboo in the formwork for the Naiju and Uchino Community Centers. The architectural forms were ultimately determined by incorporating materials and conditions specific to each location as parameters.

Moreover, the spaces created by Yoh also connote a sense of scalelessness; it may be that he saw architecture as a means to interact with the universe, as can be observed with Prospecta Toyama where the design bears minimal program in respect to human-scale activities and functions. Furthermore, a priority was given to the processes by which the role and form of space were determined with respect to their relationship with the environment.

“Drawing closer to nature, imitating nature.” These are the words Yoh used to capture Galaxy Toyama’s design. After studying economics in Japan and interior design in the United States, Yoh first pursued architecture on a trial-and-error basis. Being from Kumamoto and establishing his firm in Fukuoka, Yoh was not permanently surrounded by the richest or most stimulating of architectural landscapes. However, it was in Kyushu, at the western tip of the Japanese archipelago, that he decided to tirelessly explore the fundamentals of architecture and pursued, in a pure and rational manner, designs that harmonized with surrounding conditions. For him, the core defining factor became the integration of natural phenomena itself. Yoh gave the name of “elastic architecture” to this relentless quest based on a back-and-forth dialogue—rather than a confrontation—between man and nature, and which freely flows between the digital and the analogue.

Centre of the World

I saw Yoh in person for the first time a few years ago at a university lecture he was giving. He was reflecting on his creations until that point and openly talked about his perspective of the world. A question and answer period followed the lecture. True to himself, Yoh did not really answer the questions and mostly veered off topic, his replies being largely irrelevant to the questions. It was the first time I had the chance to hear him, and what he said felt new and different. Toward the end of the question and answer period, I addressed him: “Every creation of yours possesses a fundamental strength and integrity. You have decided to base your activities in Fukuoka, a relatively minor city. How far removed do you feel from the world?” His reply was point-blank. “You must think of yourself as the centre of the world. You stand at the top of the watershed, and water flows from there.”

Yu Momoeda was in residence at CCA in April 2019 as part of Find and Tell, a program that promotes new readings that highlight the intellectual relevance of particular aspects of our collection today.

Related residency