How to: reward and punish

A soft tactical guide for better architectural awards by Lev Bratishenko, George Kafka, Anna Hentschel, Emilienne Fernande Bodo, Shayari de Silva, Francisco Moura Veiga, Tomà Berlanda, Monica Hutton, Ioana Lupascu, and Stephen Parnell

It is not obvious exactly what architecture awards do, or if they do it well. Awards are one of the noisiest and most expensive ways that the architectural discipline proclaims what is good about itself. Yet, the more prominent awards are, the more their internal opacity makes them suspect; the more they proliferate, the more meaningless they seem.

Listen: *

Even if many awards now appear to be parasitic, extracting value from architectural labour while pretending to reward it, architects continue to play along. Why? It was tempting for us to respond with cynicism and dismiss awards as an empty game of prestige but, with a sense that there was something more to uncover, something worth caring about, we chose not to.

To better understand this instinct of ours, we conducted interviews with people who play different roles in the awards system and analyzed awards through publicly available information. Amid the noise, we discovered moments of sincerity, idealism, warmth, curiosity, and appreciation. We decided to encourage this care by publishing a soft tactical guide to help you recognize more possibilities for action when you (inevitably) encounter the architecture-awards system.

* These tracks are made of quotes from our interviews. Terms and contradictions apply.

1. Don’t get distracted; the quiet parts are the most important

Awards are more than how they appear in public and do more than just produce news. The complex processes that produce architecture prizes and the intricate differences between them are consistently hidden by the agitation of the publicity cycle.

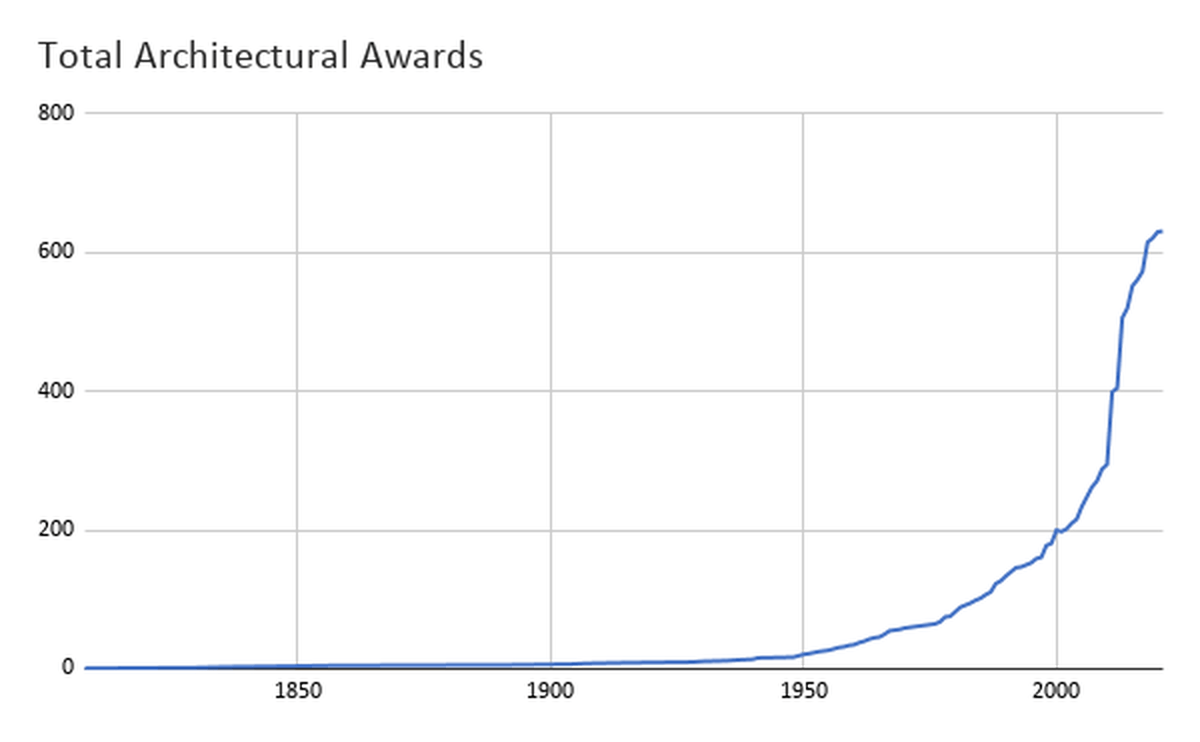

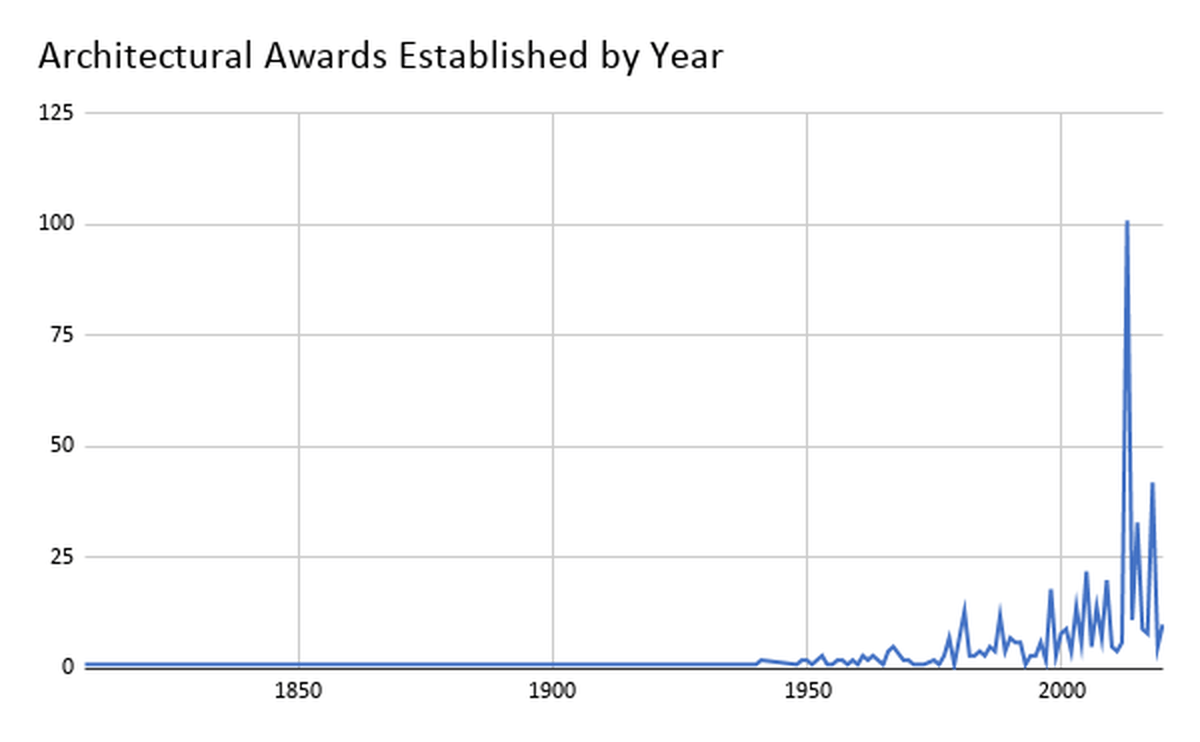

If there appear to be more architecture awards today, it’s because there are. But it’s also a result of the media’s hunger for low-cost content. An award press release is hard to turn down; it packages images with a simple story, often stuffed with recognizable names.

These names are part of the problem. For every Robert Venturi celebrated, there is a Denise Scott Brown overlooked. The history of awards is also a history of headlines about canonical individuals—mostly able-bodied white men—not a history of gratitude and interdependence. Behind all of the specific scandals lies a muted discomfort with the idea of “winners” at all in creative fields. Architecture is not the Olympics.

Listen:

This discomfort relates to how the winners are chosen. The emerging and the ignored, the rewarded and the punished are mostly picked by unaccountable jurors whose power comes from temporary collectivity and individual reputation.

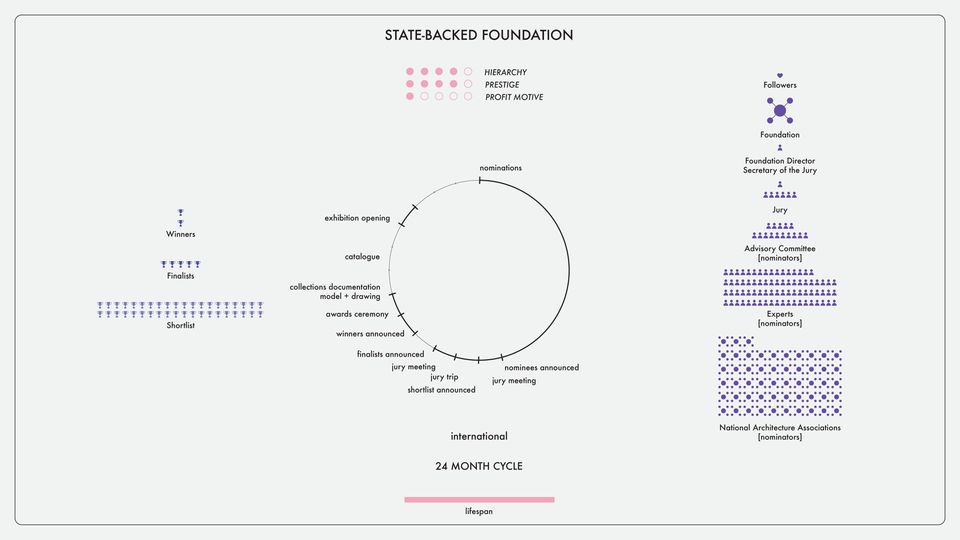

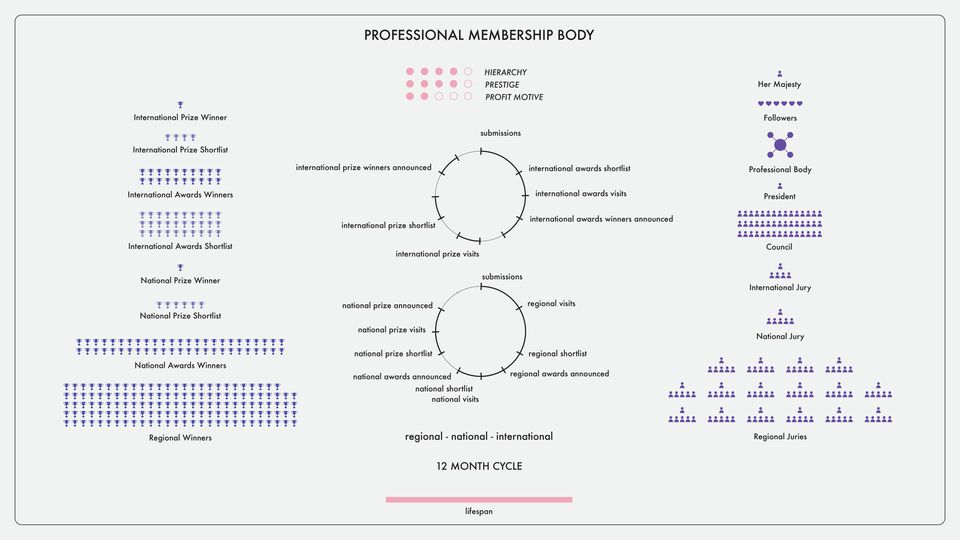

Secret deliberations play a key role in the spectacle of the reveal, but secrecy hides the discussion of a project’s finer merits or shortfalls, along with the personal and political dynamics that everybody knows affect jury decisions. Behind the juries are people even less public-facing: the bureaucrats, organizers, nominators, administrators, ceremony planners and applicants—an institutional network that produces architectural knowledge, as well as news.

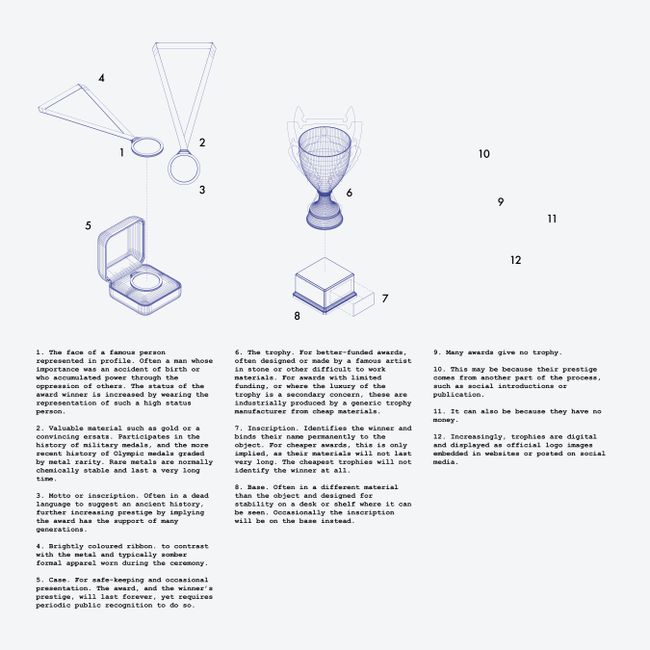

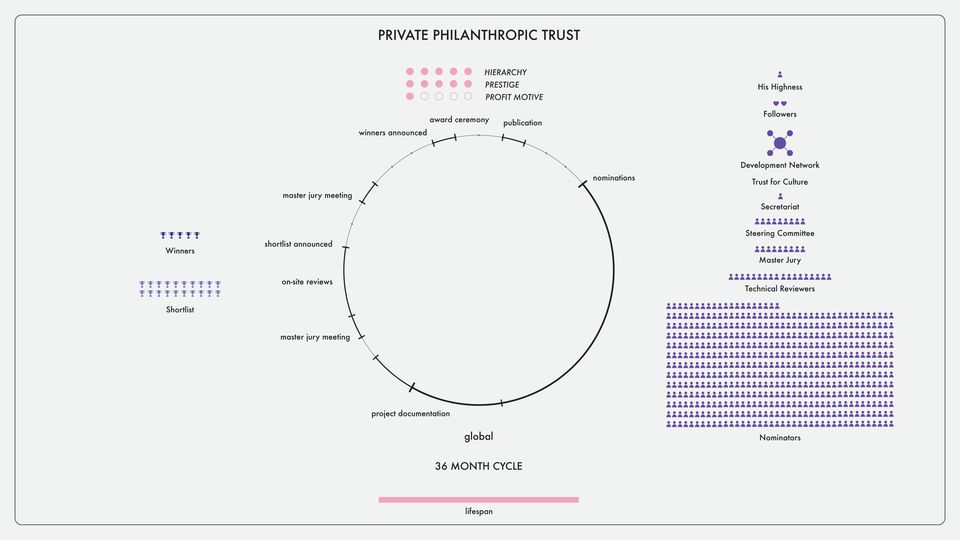

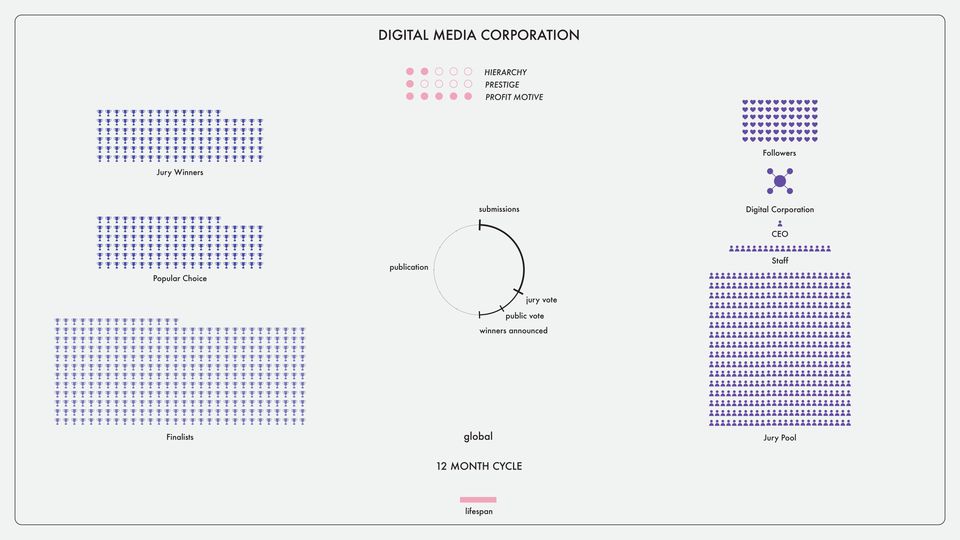

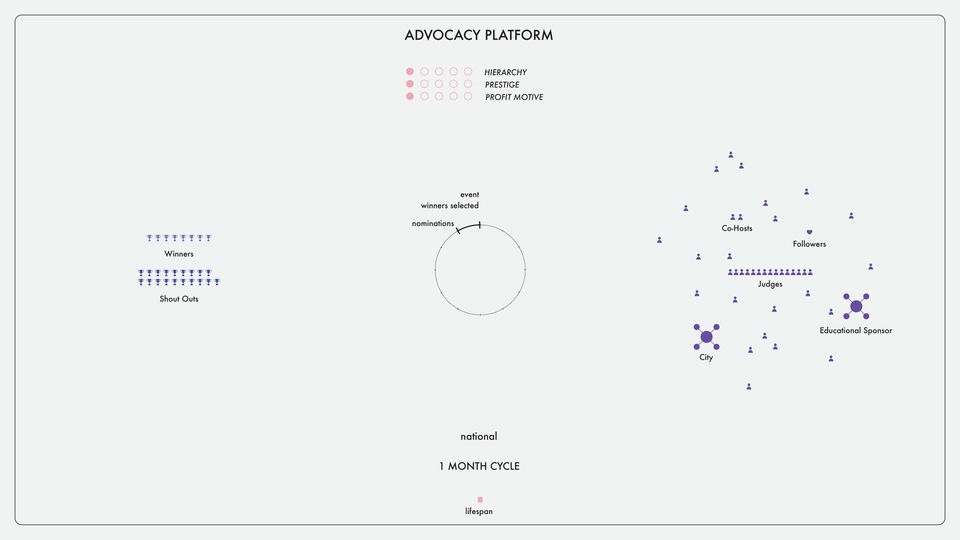

These awarding bodies extend beyond the medals they give or the winners they declare. One way to categorize them is according to how hierarchical or how interested in prestige they are, and how badly they need money.

Carefully designed hierarchies of nominators, juries, secretariats, boards, and committees hold unevenly distributed power to dictate who may nominate, vote, veto, or spectate. Their relations are shaped by the rules, regulations, protocols, fees, and codes of ethics that, in turn, reflect the institutions that created them. Yet bureaucratic structures are always full of opportunities for subversion: their complexities give them many pressure points, where a minor change could have unexpected or significant effects.

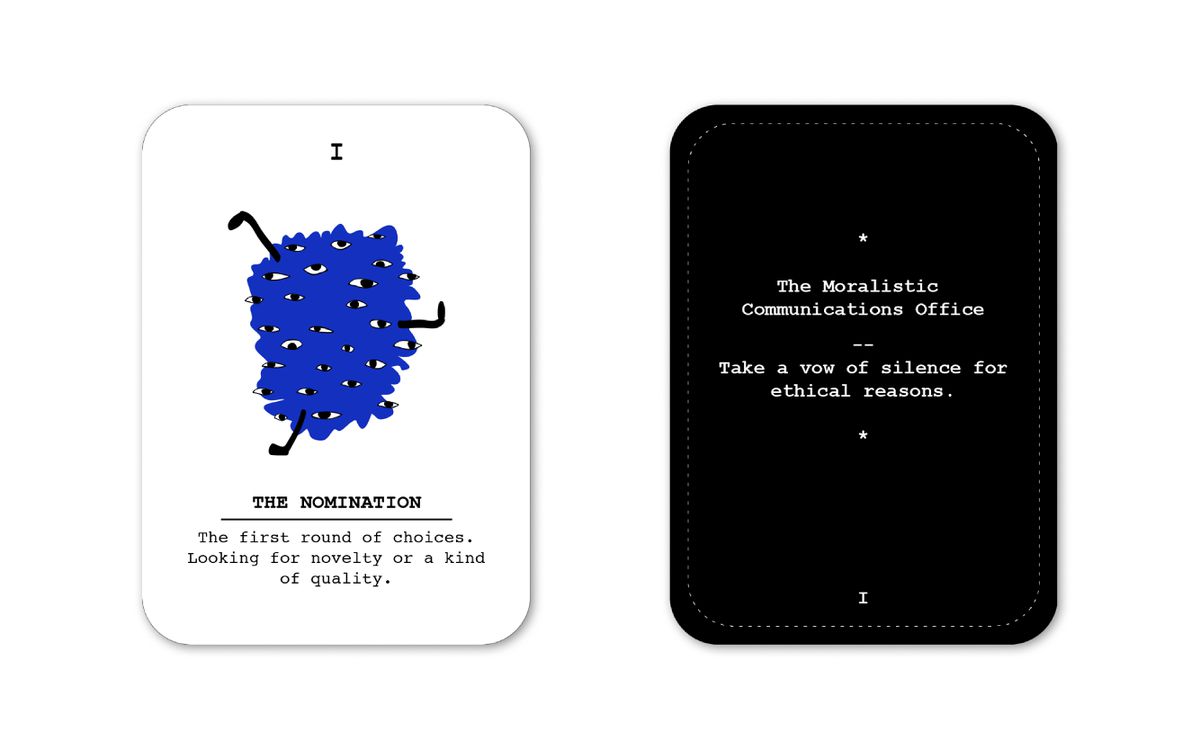

Any actor can forget, accept, reject, modify, or simply ignore procedures; and if many actors intervene at each stage, an entirely new process can emerge. It can begin as easily as drawing a card:

Our Joker cards may prompt new relations and interactions between you, the others, the award, the prestige, and the punishment, at each stage of the typical awards process. Changing roles can lead to greater awareness of the game’s mechanisms.

Warning: Use of the Joker cards can cause increased questioning of the predominant protocols of architecture awards. Play with lust and seek disturbance. The full set of 79 cards is available to print and cut-out or as a poster.

2. Beware of self-perpetuation

Where does the desire for awards come from? The building is complete and handed over, the client has moved in and seems happy, the photographer has captured its essence, the publicist has translated it into a press release, the critics have written their appraisal, the guest lectures have written themselves, and yet there’s still something missing.

Is a building only truly complete when it is decorated with accolades? Can a self-respecting practice practise without advertising itself as award-winning? Will it be noticed in another country? An architecture-awards industry has emerged alongside traditional media and public relations to calm these anxieties, selling professional well-being in the form of awards.

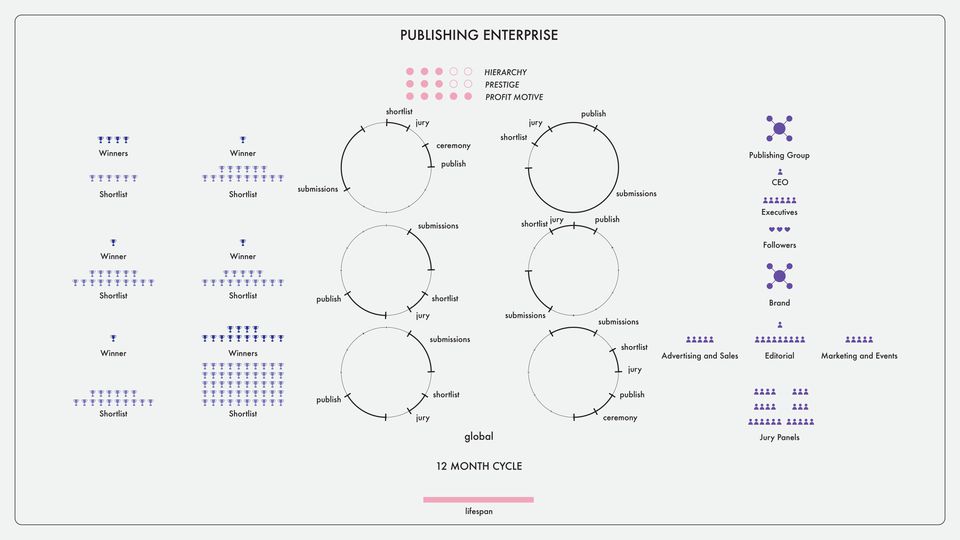

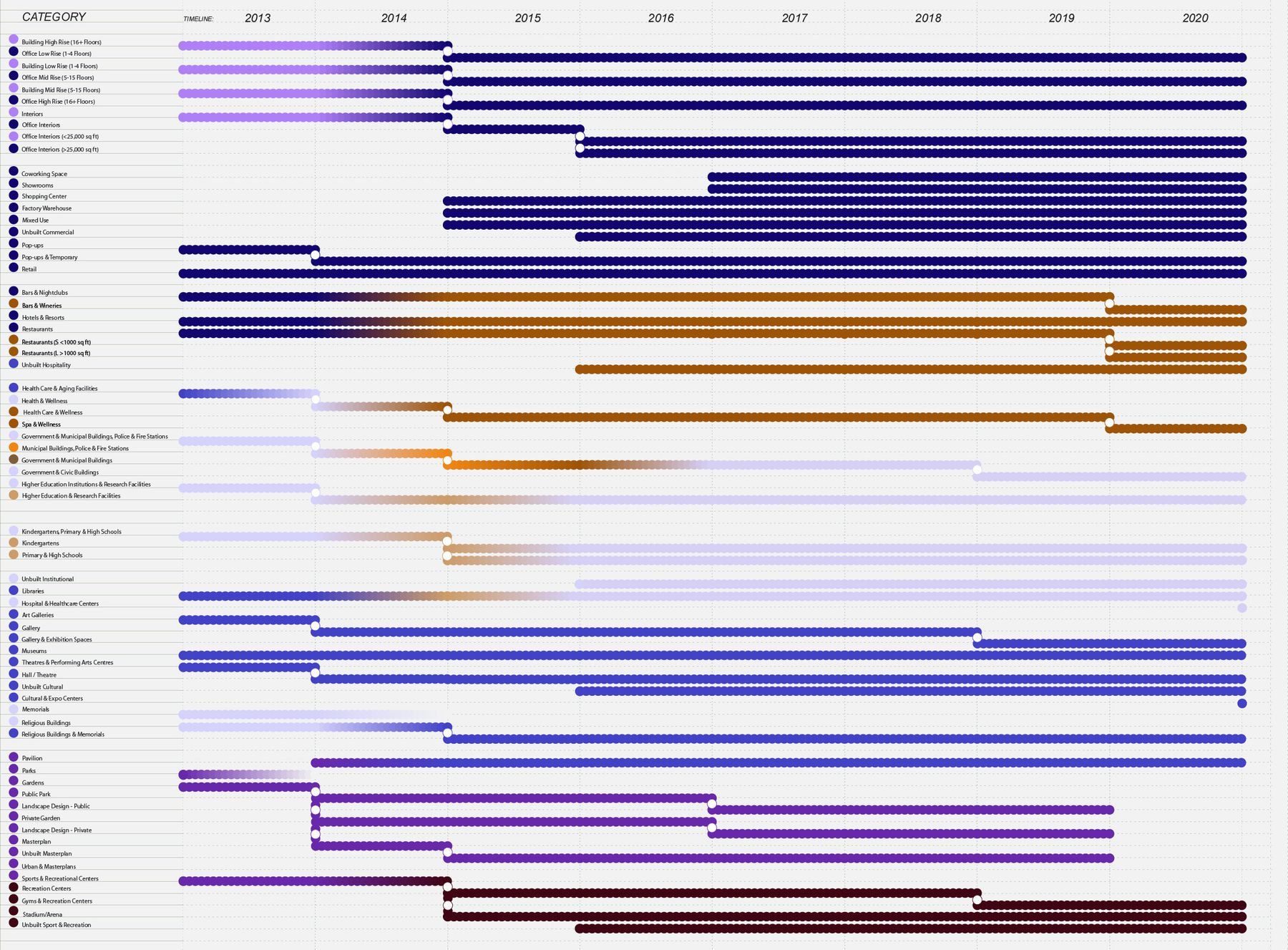

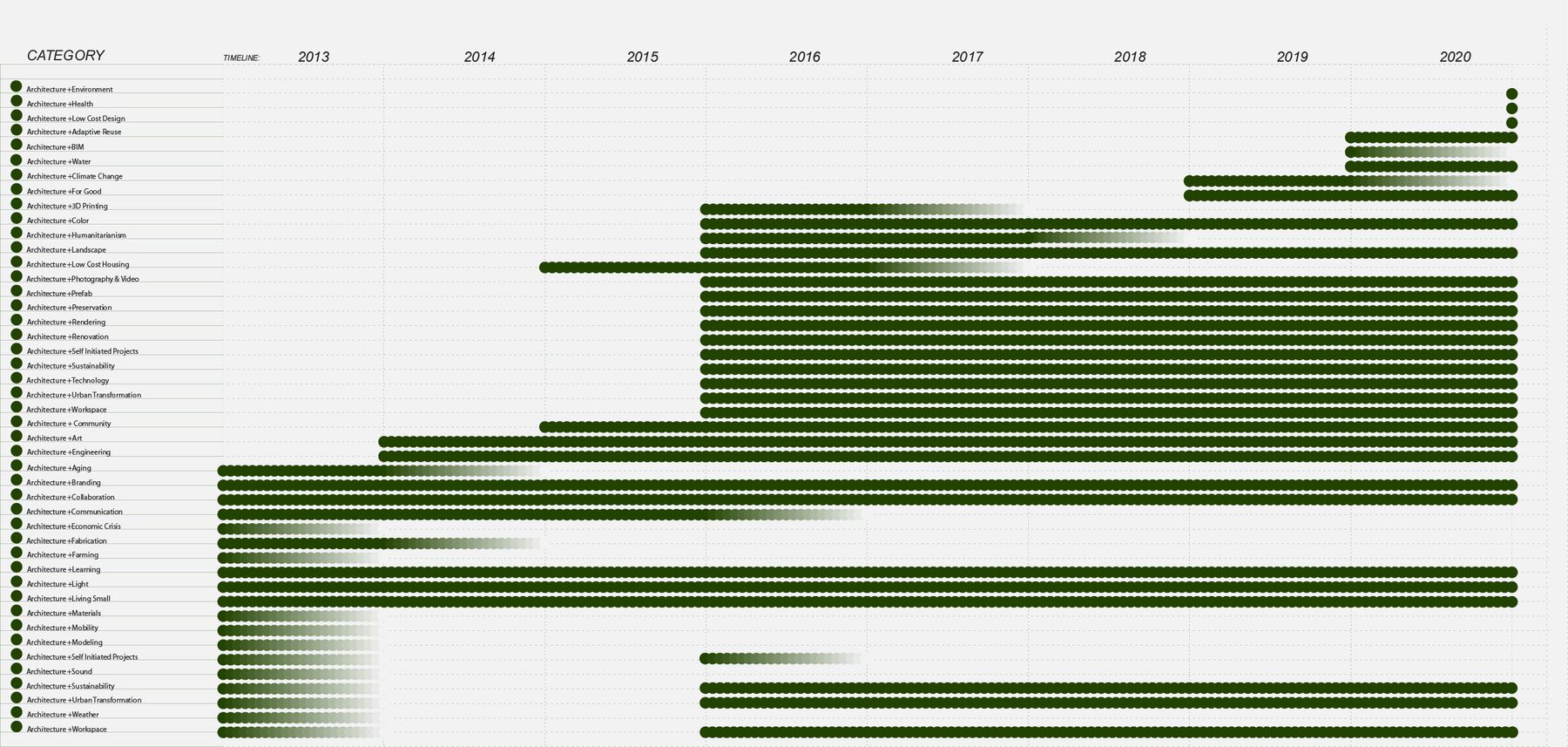

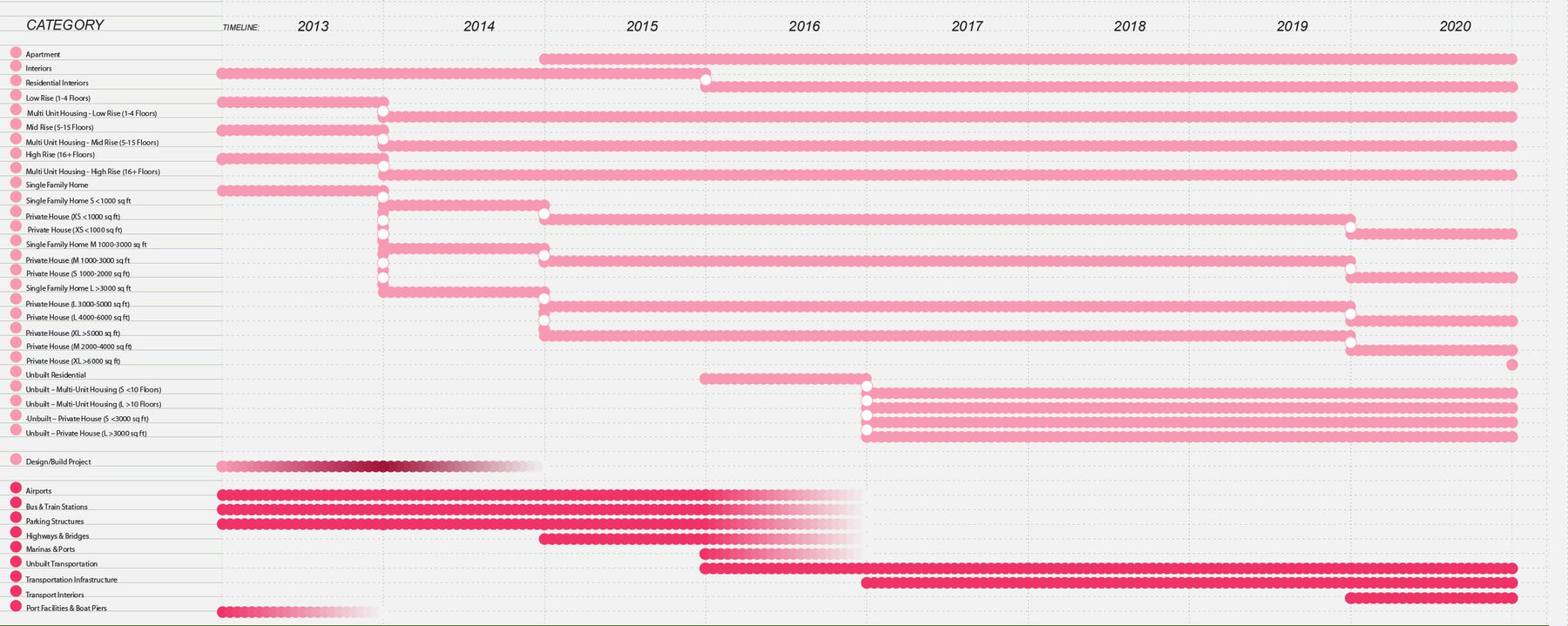

It is a sector that sustains itself—and increasingly supports traditional architecture media—by constantly creating new categories, following trends and pruning awards that are no longer relevant. The architectural media company Architizer is a case study in how to meet the market’s demand for awards. Essentially a portfolio site for architects to show their work, it introduced an awards program with 51 categories in 2013, and since then, the A+ Awards program has blossomed to over 120 awards. Fee-paying entrants need to believe they can win, so when one category becomes too popular, it buds into two or more.

If there are limits to this business model, they are not yet apparent. Perhaps when eyeballs are the goal and prestige is just the by-product, award-givers can print their currency without ever risking its value. From an entrepreneurial perspective, increasing the accessibility of awards is the same as growing revenues, and diversity is indistinguishable from penetrating emerging markets.

It seems the recipient’s gratitude for an award should be influenced by the giver’s motivations. Some architects do have less respect for awarding institutions whose interest in self-perpetuation is immodestly apparent, compared with those awards with credible claims to an intellectual agenda, but obviously there are enough who don’t care, since the sector is thriving. Presumably because both kinds of awards work, in that they are able to generate publicity. If both kinds of awards make people feel appreciated, who can say that they are wrong?

The further you go from the profit motive, the more complex are the motivations for giving awards. For institutional award-givers such as universities, museums, and private foundations, awards are another tool in their toolkit, and increasingly one with added risk. Where associating with an individual’s legacy was once a shortcut to prestige and reputation, it now rightly attracts scrutiny and accountability.

Listen:

An award may be named after a Nazi sympathizer. Or, if the diversity of winners is consistently limited, there may be an uncomfortable moment of reflection about how and for whom an institution governs itself. And if an institution decides to abolish its awards, who loses? The winners? The architecture discipline? The awards industry? Or just the institution?

“Each new prize that fills a gap in the system of awards defines at the same time a lack that will justify and indeed produce another prize.”

James English, The Economy of Prestige

Looking at origins and motives for giving, we were interested to discover that public speeches have been particularly good at seeding new awards, even if this was not the intention of the speaker. Like giving a speech or publishing a text, creating and giving an award is a useful and recognizable way of publicly claiming a set of values, or at least identifying with someone else’s.

A speech by US civil rights leader Whitney M. Young Jr. at the 1968 AIA convention, for example, led to an award that recognizes architects embodying social responsibility. Charles Philip Arthur George Windsor-Mountbatten’s speech at RIBA’s royal gala evening in 1984 led to Building Design magazine’s Carbuncle Cup for worst British building of the year. More recently, a Solange tweet helped inspire the Sound Advice Awards, a “visual and sonic carnival” in celebration of under-appreciated spatial practitioners in the UK. If you’re looking for a foundational text to set the values for a new award, we have a few recommendations:

- Rebecca Solnit’s essay “When the Hero is the Problem”

- Scaffold podcast Episode 43 on Sara Hendren

- Caleb Femi’s poem “Yard”

- Bifo Berardi’s lecture “On Futurability”

- Martin Scorsese and Fran Lebowitz’s series “Pretend It’s a City”

- Paul Preciado’s essay “Learning from the Virus”

3. Get over winning and losing

The proliferation of architecture awards, in particular since the 1970s, can be seen as another symptom of the neoliberal paradigm that reduces human relations to competition. The increase also reflects reinvigorated politics of quantification and classification, with historical roots in rigid class structures, imperialism, and colonialism, now retooled by the digital revolution. With technocracy and neoliberalism in mutual crisis, the contradictions of today’s awards system mirror a larger conflict over whether value is defined in economic terms or human ones.

Some recent awards appear to consciously resist the trend to lionize individuals or reinforce stratification; their competitive parts are not the most interesting thing about them. The Royal Academy’s Dorfman Award, for example, was designed to seek out international talent. It brings nominees to London for a week of conversation and creates annual cohorts through shared experience. The Architectural Review‘s Emerging Architecture prize also gathers its shortlist together. Both still announce single winners, but there are meaningful personal exchanges in these judging processes that contrast with other, more extractive prize protocols.

“Positive social change results mostly from connecting more deeply to the people around you, rather than rising above them.”

Rebecca Solnit, “When the Hero is the Problem”

Other prizes contribute to an emerging ecosystem of research that parallels the traditional academic one. For over forty years, the Aga Khan Award for Architecture has been constructing a global network through its intense project-review process, seminars, and other public programs. Each round of the prize cycle increases its archive documenting architecture in the Muslim world. The EU Mies Award has accrued a smaller repository of projects representing “European” architecture. In an archive, the difference between winners and losers is nominal at best.

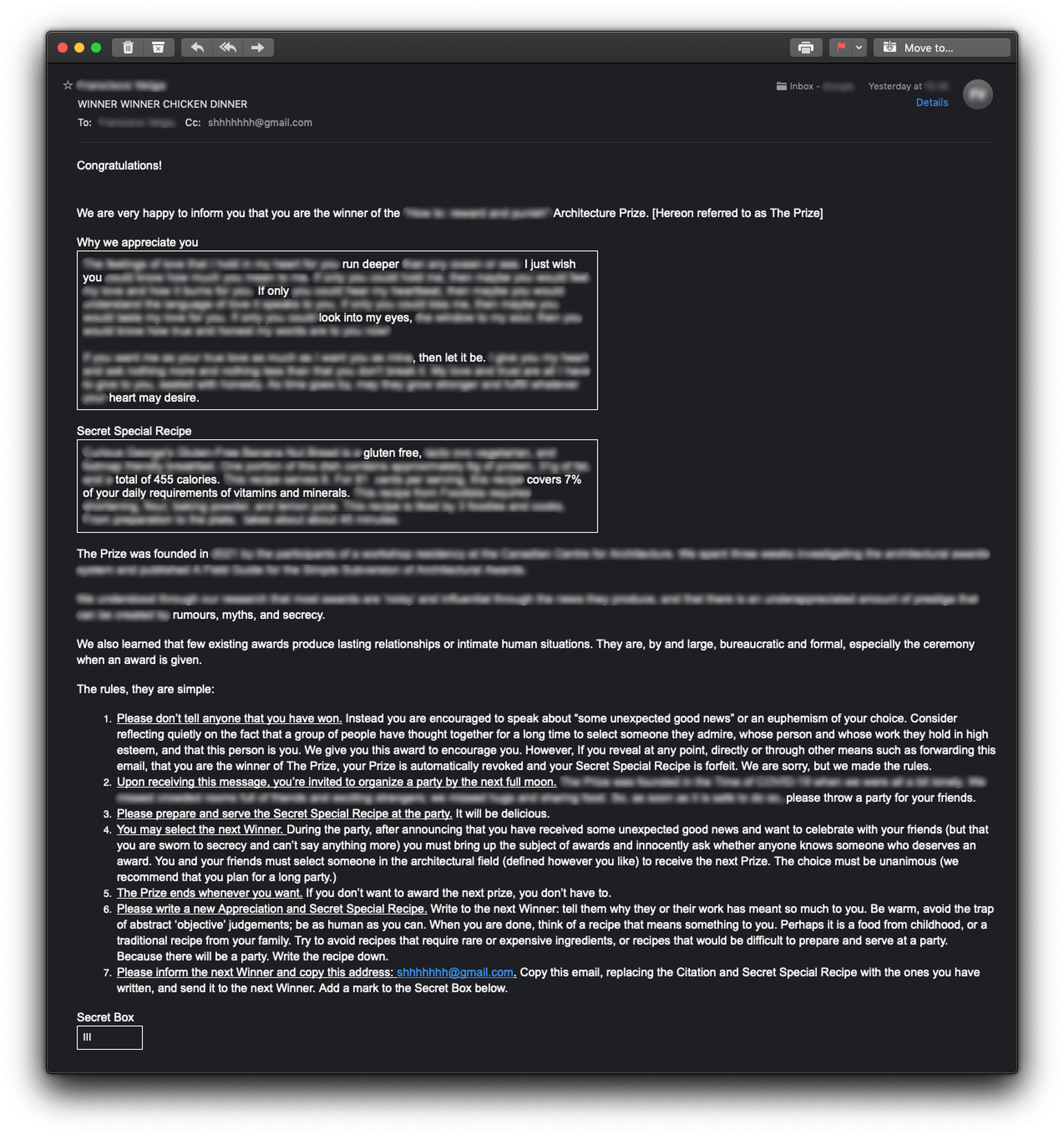

There are also awards that completely reject publicity. When one of our interviewees talked about an award whose winners are sworn to secrecy, we didn’t believe them until we saw this email. This is an interesting new typology: cheap, warm, and out of its organizers’ control. What if the end of the awarding process was, instead, the beginning of a conversation? We were not sure if we should publish the email or not, but we decided to include it. Perhaps it will inspire someone.

Finally, there are rewards that do not claim to be awards, like magazine monographs, which announce that a practice has built enough to be taken seriously or, at least, that it cannot be ignored anymore, or heritage listing, which, because it protects buildings from demolition, has a more direct impact on cities than most awards.

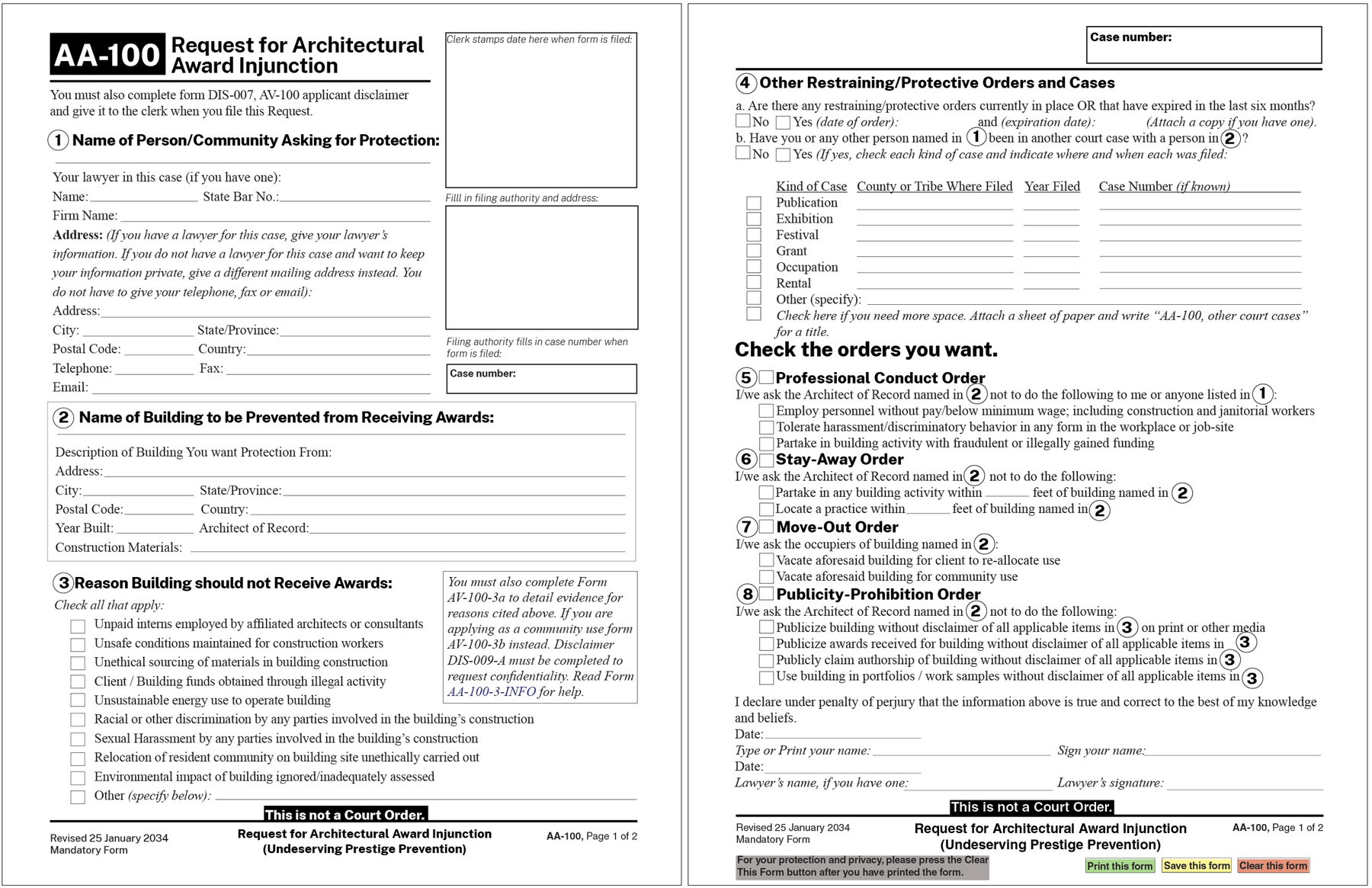

Other forms of discipline are possible. The prestige of being an award-winner has traditionally protected certain individuals from public scrutiny. Can this privilege be inverted?

If you want to be noticed along with your intervention, find inspiration in a public tactic like the one above. If you are shy, act quietly in the bureaucracy. If you’re out for blood, you already know what to do. Choose appropriate methods.

The possibility for tactical action depends on an understanding of environment. Like architecture publishing or public events, awards are a para-architectural field where values are contested and performed. Though awards are probably the best of these at breaking out of the architectural bubble and briefly reaching to a mass audience, their power to speak comes at the price of limiting what they can say.

The prevailing award system makes it very hard to recognize our underlying impulse to appreciate people or to imagine what else awards can do.

We have tried to make it a little easier with this guide.

P.S.

On Exactitude in Awarding

In that Empire, the Act of Awarding attained such Extension that the award-winning buildings in a province could add up to a city, and the award-winning buildings in the empire would make up a province. In time, those Unconscionable Awards no longer satisfied, and the Awards Industry created an award so embracing that each building could be awarded it, to the point this did in fact happen.

The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Awards as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Awarding criteria was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of archives and unplugged websites. In the depths of filing cabinets and back-up servers, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Award, inhabited by long forgotten emerging and established; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Architecture Awards.

Eduardo Luís Albert, The Travels of Prudent Gentlepeople, Book IV, Cap. XLV, Montréal, 2051

Based on “On Exactitude in Science,” a short story by Jorge Luis Borges.

Everything in this publication was produced over forty hours of video chat, including eleven hours of interviews, fifty-nine pages of notes with over eighteen thousand words, and a sheet tracking over 400 architectural awards. It was only possible through the resolute optimism of all the participants and the generosity of our interviewees: Amanda Baillieu, Daniel Lobo, Diane Gray, Eleanor Beaumont, Gloria Cabral, Hanif Kara, Joseph Henry, Kate Goodwin, Katty Law, Manon Mollard, Moises Puente, and Tony Chapman.

We also thank advisors, critics, and friends whose conversations shaped this project and made it possible: Francesco Garutti, Giovanna Borasi, James English, Julia Albani, Rafico Ruiz, Martien de Vletter, and Rory Ross Russell.

Special thanks for research assistance to Iro Kalargyrou.

How to: reward and punish was directed by Lev Bratishenko, Curator, Public, CCA with writer and editor George Kafka.

How to is a series of accelerated annual residencies that bring small teams together at the CCA to produce a new tool—physical, digital, or somewhere in between—and rapidly begin to address a specific opportunity or need.