Jury general comments

Congratulations to all the teams! The jury was impressed by the range and diversity of the submissions and the apparent multidisciplinary approaches within and among the projects. This is a compliment to the CCA and the charrette organizers who are inspiring a new generation of practitioners and the community at large with the charrette challenges for both Actions and Agitations. There were many good ideas at a wide variety of scales, several of which we think are viable for the site. We recognize that the time frame was very short and intense for a complex problématique and a challenging, interesting site. However, none of the projects successfully integrated all three challenges: urban agriculture, renewing public places, active transportation. Most teams elected to develop one or two themes, and those that attempted to integrate all were generally underdeveloped either graphically or conceptually. Given the overwhelming popularity and the currency of the subject matter, from the local food movement, to sustainable transportation, the jury expected a deeper and richer exploration of these themes. There was a tendency to slip into cliché, which is a rather naive abdication of the responsibilities of the designer. Design must necessarily be more than a seductive graphic gesture or a clever title. For example, many entries interpreted the word nourish literally, which we think was a missed opportunity to plumb the depths of the metaphor and the connections to the wider community. The opportunities afforded by the site, the unique context and the demographic conditions of the community were not fully exploited save for several projects.

Though we appreciated the distinction between the categories actions and agitations, we feel that there were not enough convincing schemes in the agitations category for us to usefully continue the distinction. We believe that the problems of urban agriculture, active transportation and urban renewal demand planning solutions which require or elicit mobilization and education.

Members of the Jury

- Paula Meijerink - landscape architect, WANTED, Boston

- Patrick Morency - Medical Doctor, Community Health specialist

- Lucie Careau - planner, Groupe Cardinal Hardy

- Nina-Marie Lister - Associate Professor of Urban + Regional Planning at Ryerson

Winners

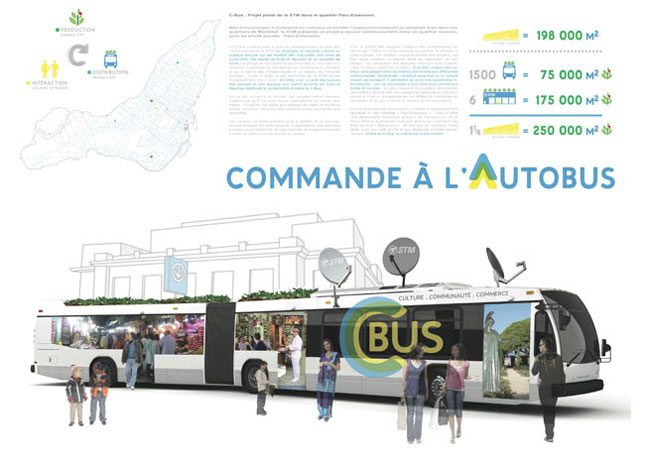

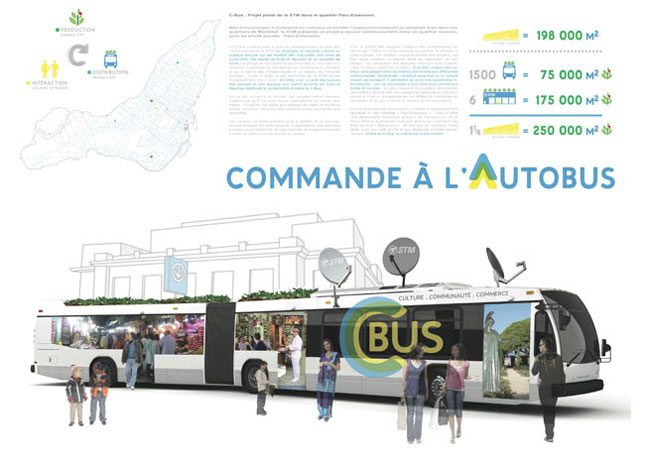

FIRST Prize - Commande à l’autobus

Université Laval

Jean-Philippe Saucier;

Jean-Bruno Morissette;

Marjorie Bradley-Vidal;

Sarah-Emilie Vallée

The jury has chosen C-Bus as the overall winner, reflecting both the Action and Agitation categories. This scheme emerged quickly as the single unanimous choice of the jury. We feel this submission is the strongest design and a complete graphic package overall: it is a convincing, elegant and clear expression of a complex idea that addresses the competition problématique. The project is convincing at several scales. While we acknowledge that this entry does not address the specific complexities, it capitalizes on opportunities at other levels beyond the local. The C-BUS scheme posits an effective coupling between the powerful STM network and the proposed fresh food distribution system. The strategy relies on the strength of the STM, which is a municipal presence in every community. The jury appreciates the simplicity of using the bus garage roof to grow the food that is then moved by the bus into the neighbourhoods. It is interesting to note that the mobile market could exist independently of the bus design — it could easily be in the form of a trailer etc. yet must rely on the STM network.

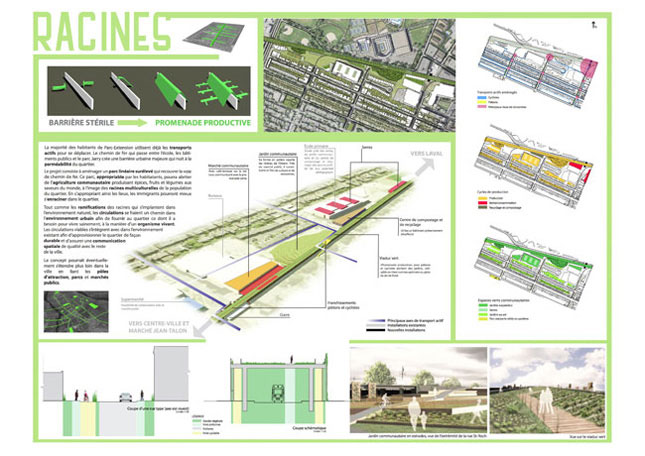

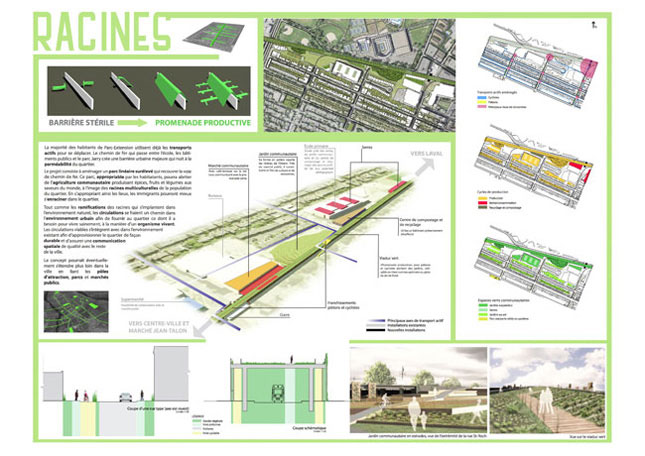

SECOND Prize - RACINES

Université Laval

Valérie Ouellette;

Marie-Alexandrine Beauséjour;

Manon Paquet;

Maude Bilodeau-d'Astous;

Andréa Isabelle

This planning strategy addresses the main barrier on the site which is the railway line through a useful primary gesture: the project reconnects the neighbourhood to Parc Jarry. Furthermore this topographic connection is activated through community infrastructure and a diversity of agricultural uses. The jury appreciates the progressive layers of intervention which are carefully considered; there is a coherent vision of the issues within each layer, from the network for active transportation to the cycle of food production, to the diversity of public green spaces. This entry shows the most sophisticated understanding of the site which begins and departs from a single clear idea: the transformation of the sterile barrier to productive promenade. The project is a well integrated expression of all three project themes focused specifically on the site.

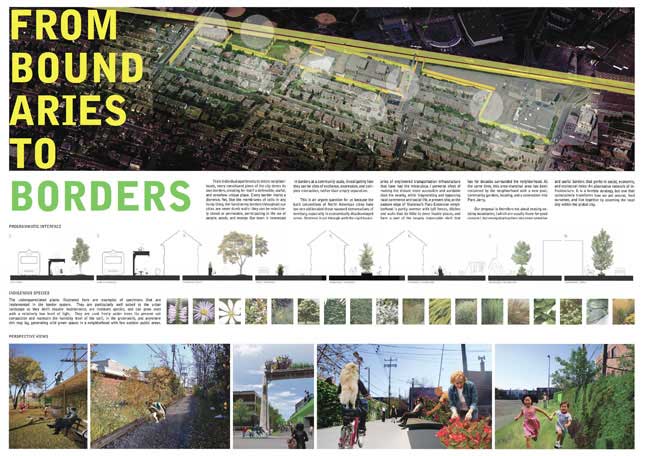

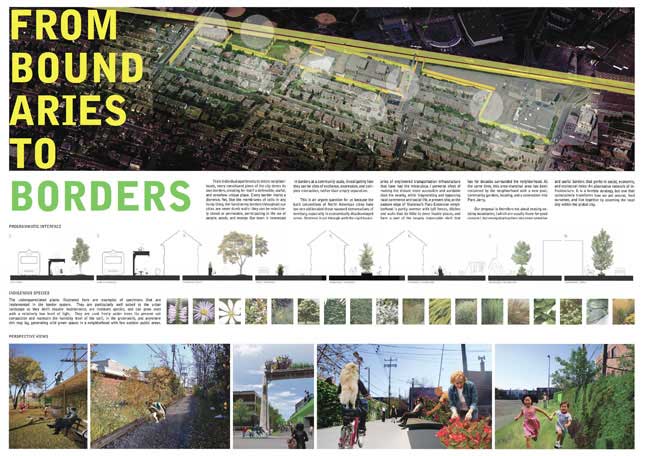

THIRD Prize - BOUNDARIES TO BORDERS

McGill University

Gabrielle Poirier;

Ksenia Kagner;

Michael Faciejew;

Simon Bastien;

Sebastian Bartnicki

The jury is impressed by the sensitive and intelligent focus on the interstitial spaces, as well as the iteration between public and private uses. While less fully developed than the other award winners, this project is graphically well presented, featuring a sophisticated focus on the notion of the edge and its translation to active borders in the context of social, ecological and infrastructural aspects of the community. A key strength of this project lies in its focus on ecological performance to enrich biodiversity, yet does not fall victim to naive reliance on native species in what is currently a hard urban landscape. The scheme suggests that residents can appropriate individual space through gardening and stewardship activities, thereby extending the public realm. In the perspective views, which offer insight into and speculation on the themes, the raised bike path is not viable.

HONORABLE MENTION - ME eT' LA TABLE

Université de Montréal

Amélie Marsolais-Ricard;

Valérie Daoust;

Marc-André Massé;

Bryan Marchand

ME eT' LA TABLE is a noteworthy project because it reallocates road space to other uses at an appropriate scale, and it addresses recreation in all seasons. The modular system of furniture and planter boxes can be implemented at a variety of scales, from a road segment to pockets. The rendering shows the project quite well.

Nourishing the city through landscape

Cities are pre-eminent among the creations of humankind. Rich sources of inspiration and opportunity, and incomparable as human habitat, they are—or ought to be—constantly in transformation thanks to their complexity, diversity, and uncertainty, ceaselessly being recalibrated and adapted, like any ecosystem, to their changing population. The transformative qualities of cities present ongoing challenges to all fields of design. These characteristics have also made cities an ongoing challenge for design, with many efforts made on a trial-and-error basis over the past century to design and build 'good' cities. Alas, these have tended to neglect the richness of the landscape contexts in which all cities sit and of which they are irrevocably part. If the human desire to engage with the natural processes that sustain life can be neither denied nor suppressed, it seems ironic that we have tended—especially in the Anglo-American world—to resort to escaping the city instead of exploring its many possibilities as a living landscape. It is symptomatic that most of the food consumed in urban areas comes from somewhere else, suggesting a certain denial of basic requirements for human well-being.

Public space is ideal for the development and expression of community identities, and it moreover can facilitate the vitality of a many business, cultural, and social activities. The potential is great, especially in a city like Montréal, where new spaces are being developed to complement existing squares, public markets, and parks. Fuelled by a vibrant civil society, underutilised spaces are becoming new public places such as community gardens. Such transformations give us cause to hope for the best. Yet questions remain: is space being allocated equitably and fairly among various transportation modes? Have we yet come to terms with the impacts of the urban space turned over to the automobile in terms of these changes to the urban environment? What consequences arise?

North American cities are marked by a familiar story: the explosive increase in the distances we now have to travel in order to meet our basic needs since the rise of the automobile in the mid-20th century. Residents of cities and suburbs are left with few options other than using their cars to stock up on industrialised, standardised, imported foodstuffs instead of making a short daily trip on foot to find fresh, inexpensive, varied, locally-produced food. A dearth of physical activity and an abundance of poor-quality food conspire in ways that account for alarming rates of obesity and heart disease among those who find it easy to afford the food available in supermarkets. The cost of healthy whole foods, dictated by the corporate-dominated commercial food industry, is frequently too great for lower-income populations, leaving many people, particularly children, prone to nutritional deficiencies.

Our situation is absurd: rather than maintaining a direct convivial relationship with the sources of our food, we depend on a complex system of consumer-oriented importing based on motorised transportation (which paradoxically reduces access to locally-produced foods). Food insecurity is quietly and insidiously growing in the city; Montréal is hardly the only region in North America where this situation prevails. Climate change and scarcity of fossil fuels make us fear the worst about our ability to supply food to the urban areas in which the majority of the planetary population now lives.

Instead of biologically diversified, productive spaces, our urban environments are riddled with purely symbolic decorative green spaces, mostly lacking any ecological or productive function. Urban quality has been neglected in favour of the suburbs. Among the effects: the obliteration of the marvellous uncertainty of cities in favour of strict parameters strictly controlling how activities are mixed, how built form relates to open space, and through presumptions about how people ought to move about (by motorised vehicles). The city is thus reduced to a predefined, automated mechanism rather than a mixture of various open and interconnected systems that behave as self-organising ecosystems, allowing the emergence of an infinite variety of adaptations and exchanges between nature and culture.

The challenges are clear. We must nourish the city from ‘within’—to reintroduce urban agriculture in the urban core, and to integrate this production into a network of sustainable redistribution of food resources connected to the bioregion in a relationship based on respect; to place more emphasis on the quality of public space; and to make it increasingly possible for people to travel by foot, bicycle, and public transit (everything that is captured by the term ‘active transportation’). In the Montréal case, many citizens and community groups have mobilised to create productive gardens of all sorts so as to grow their own healthy foods. We must also come to terms with the length and harshness of our winters, which make us dependent on food imports for several months of each year.

We must therefore rethink our metropolitan regions by considering their qualities as living contexts. We must seek conviviality in how we meet our basic needs, namely housing, food, self-development, leisure, and transportation. The challenge is fundamentally a question of design—one that enfolds all scales, and one that we recognise through the hybrid practices known as urban design, landscape urbanism, and ecological design. All of these are means to explore the different possibilities for sustainability, bringing us to overcoming the supposed gaps between nature and culture.

Site context

The area of intervention chosen for the 2009 charrette is Parc-Extension. As its name indicates, this neighbourhood is an ageing 20th-century suburb district created—albeit indirectly—as part of the 19th-century city-building project conceived by Frederick Law Olmsted, the Mont-Royal Park system, which sought to reconcile nature and culture. Parc-Extension was also part of a vast industrial network linked to the railways, whose tracks also defined the neighbourhood’s southern and eastern boundaries. From the early 20th century until the 1960s, Parc-Extension gradually grew out with an orthogonal grid of streets, filling the space left between the railway lines, the Town of Mount Royal, and the Autoroute Métropolitane (40). These infrastructure elements now hem the neighbourhood in on all sides, making it an enclave. Many strategies have been advanced in recent years to link it through walkways, bicycle paths, and public transit with its urban neighbours in adjacent city districts.

Parc-Extension is now a densely populated urban neighbourhood with a significant population of recent immigrants who, despite a certain vulnerability to poverty and exclusion, give the neighbourhood its vitality, vibrancy, and uniqueness. The neighbourhood comprises includes many families occupying their first home in Québec, many of whom are renters; these residents are from over 100 different ethnic groups (a more detailed description of which follows below).

This neatly-contained neighbourhood has undergone a number of positive changes in response to its new effervescence: renovation of the former Jean-Talon Canadian Pacific station, revitalisation of rue Saint-Roch, conversion of William Hingston High School into a multi-purpose community centre, the opening of a public swimming pool and multilingual library, and the insertion of collective and community gardens. All of these initiatives are cause for hope, but much remains to be done. Many sites have not yet benefited from the positive changes, or seem even to impede the development of public life worthy of the term. Certain interventions meriting the description of bloody-minded utilitarianism serve only to encourage the considerable vehicular traffic that passes through the area between downtown Montréal and autoroutes 40 and 15. Other purely functional features of the study area leave few opportunities for community appropriation that can endure.

Despite problems of poverty and certain instabilities, Parc-Extension benefits from the richness of its family and interpersonal cohesion, and the rate of socially disadvantaged residents is relatively low. Is this wealth of social networks the only key enable the residents of Parc-Extension to improve their lot in life? Can we not find ways to more fully express the neighbourhood’s social vitality and the diversity of its origins in the public realm, especially the streets and laneways? Of primary importance is linking this potential to the revitalisation of these public spaces, energised by innovative and diversified urban agriculture and by movement systems privileging efficient active transportation. Parc-Extension is fertile ground, full of opportunity for the exploration of manifold interventions that can redefine public space, biodiversity, food production, and active transportation.

The project

The 2009 Interuniversity Charrette challenges participants to tackle the broad and admittedly immense task of reconciling urban culture and nature. The specific mandate for NOURISHING THE CITY involves exploring ways in which we can build on the strengths of Parc-Extension to make it a more viable, convivial, and sustainable urban context. It centres on three key premises:

- 1. Rethinking and remaking public space for people ;

- 2. Exploring opportunities for urban agriculture ;

- 3. Affording active transportation.

Considerations

Parc-Extension differs from other Montréal neighbourhoods more in terms of its resident population than in its built environment or its urban heritage. First and foremost, it is remarkable for its high proportion of recent immigrants: 67.6%, according to data from the CSSS de la Montagne, of whom more than a quarter (27.6%) are currently in the process of obtaining Canadian citizenship—a much higher rate than for Montréal as a whole. Nearly half the residents of Parc-Extension (46.1%) did not live there five years ago. This means that for thousands of immigrants, this district is a doorway to Montréal and Québec, to say nothing of the rest of North America.

How does the presence of this large immigrant population, mainly from South Asia, North Africa and the Caribbean, express itself in the public sphere? What opportunities are there to create points of contact and a truly public forum to support the integration of these newly-arrived residents integrate themselves into their new context? How can urban agriculture enrich the development of social cohesion, cultural expression, and local food production? It goes without saying that immigrant populations enrich our local food system through the bounty of their culinary and agricultural wisdom [1].

Immigrant populations that are just getting settled in their new country must often deal with some instability. Of the 101 Montréal neighbourhoods defined by the Direction de la Santé publique, Parc-Extension ranks 100th in terms of material poverty [2], but it fares much better in terms of social networks. At 16th among 101, Parc-Extension is in a better position than the average Montréal neighbourhood with respect to social advantages [3]. This can be explained by the low proportion of people living alone or single-parent families in Parc-Extension. Of all families in the neighbourhood, those with more than two children represent 20.9% (versus 15.2% for Montréal as a whole). Grown children—sons and daughters over 25 years of age—often live with their parents. In other words, Parc-Extension is a young, densely-populated neighbourhood. Perhaps it can be said that the existing housing stock is inadequate for the needs of these typically large households, is it possible that public space could offset the current shortage of private space?

Parc-Extension’s being a neighbourhood filled with children and young adults. Most of its residents move about using active transportation (public transit, bicycle, and walking) for work, school, shopping, and recreation. Unfortunately, it is also one of the neighbourhoods in which accidents involving cyclists and pedestrians are the most numerous, with children aged 5 to 14 being the most at risk [4]. How can public space be reorganised in Parc-Extension so as to make it more user-friendly for everyday activities such as going to work and to school, to provision the household, to tend the garden for family meals, and so on?

Notes:

[1] «La production et la transformation alimentaire est un incubateur des talents d’entrepreneurship des groupes ethnoculturels, qui peuvent trouver dans des entreprises alimentaires le meilleur rattachement à leur héritage culturel» L. Bertrand (2002). Spatialisation de l’approvisionnement alimentaire sur l’île de Montréal (Presentation made at the OMISS Seminar).

[2] Direction de santé publique, Agence de la santé et des services sociaux de Montréal (2008). Regards sur la défavorisation à Montréal : CSSS de la Montagne.

[3] For a better understanding of what disadvantaged means, consider two distinct types: material disadvantage (the indicators of which are level of education, employment and income); and social disadvantage (the indicators of which are the proportion of people living alone, separated or divorced and the proportion of single-parent families). The interaction of these two types of disadvantage allows us to better understand how the social profile of a neighbourhood is formed.

[4] P. Morency (2005). Distribution des accidents de la route dans Villeray-St-Michel-Parc-Extension, Distribution géographique des blessés de la route sur l’île de Montréal (1999-2003).

Intervention zone

The site is defined as follows:

- ... on the east by the railway, a definitive physical, functional, and symbolic barrier predating the growth and consolidation of the urban fabric of Parc-Extension.

- ... on the north by the back of the têtes-d'îlot on the south side of Jarry, but not including the buildings there in their entirety.

- ... on the west by the built form lining the east side of Querbes.

- ... on the south by the armature-forming buildings on the têtes-d'îlot on the south side of Ogilvy.

The site includes three major components:

- 1. An array of coarse-grained built form including the Gare Jean-Talon and a complex housing offices for the local borough government, as well as the Complexe William-Hingston.

- 2. The large park space of the Parc St-Roch, which includes community gardens.

- 3. An extensive fabric including plexes and walkups, mostly dating from the middle of the 20th century, but also a new townhouse complex at the eastern end of Rue St-Roch (which does not yet appear on orthophotos or CAD plans).

Teams are reminded to focus on strategies that could be reproducible across the fabric of Parc-Extension and in other mid-century inner suburbs.

Site: (

view hi-res PDF)

Site highlighting the city fabric: (

view hi-res PDF)

Explore context in a larger map

Explore context in a larger map