Scale and measure in the shapes of money

Juan Campanini and Josefina Sposito map the physical imprint of the Argentinian currency

The Shape of Money, produced by the CCA with Juan Campanini, Josefina Sposito, and Martin Huberman as part of the CCA c/o Buenos Aires program, 2021 © Juan Campanini, Josefina Sposito

Since its inception, YouTube has repeatedly hosted a kind of video which, with variations, revolves around the same mystery: what physical space does money occupy at a large scale? The proliferation of these audiovisual narratives and their success on this platform, attracting millions of views each, demonstrate the prosaic curiosity for money in its most tangible form.

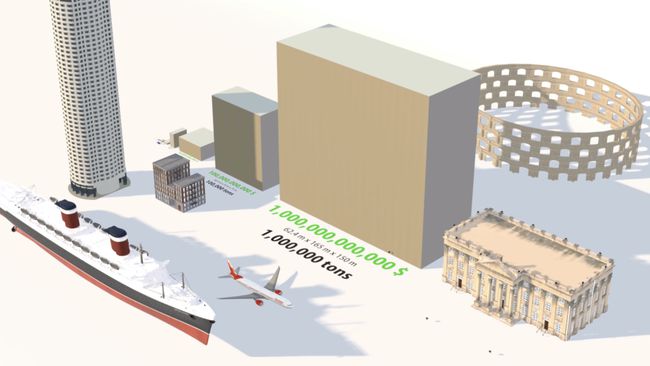

YouTube, How BIG is One Trillion Dollars?, 2018. © Animated Stuff

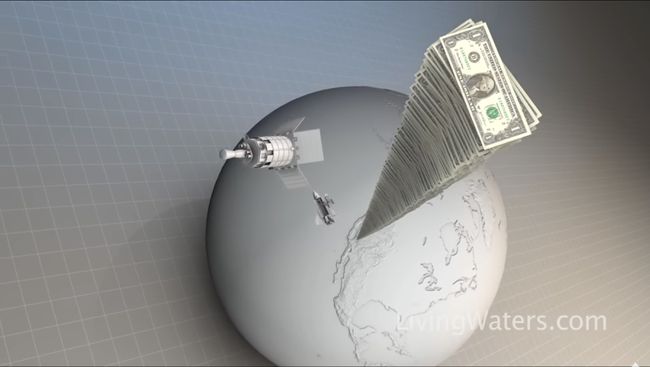

YouTube, What Does A Trillion Dollars Look Like?, 2010. © Living Waters

To make the physical dimensions of the accumulation of money obvious and easily understandable to any casual viewers, most of the videos repeat the same format: a three-dimensional visualization of known objects, their only point in common being their ability to apportion scale to something that, previously, we knew only nominally. If, with the boom in the virtuality of money, it is still relevant to ponder its physical condition, this question is undoubtedly even more pertinent in Argentina.

The economic crisis of 2001 and 2002, with the sudden retention of citizens’ savings by the state and banks, prompted an abrupt and traumatic breakdown in the already turbulent relationship between citizens and the financial system. It also brought an end to the aesthetics of security designed over years for bank architecture. Its great doorways and imposing façades then became the backdrop for popular demonstrations, while the treasures and vaults below remained unknown, heightening the mystery shrouding everything in the collective imagination that can be named but is not known. Widespread uncertainty eliminated savers’ ability to visualize their money in a huge underground safe. Their cash, which they had deposited in person, was gone—it had no physical location, no longer existed. As a result, the compulsive need to make money tangible (and therefore safe) transformed and multiplied its nature, moving away from the banking system and converting the underground treasures of la City Porteña into just one more example of the form of money.

In this respect, construction and “brick savings” emerged as a concrete alternative to deposit long-term savings, an opportunity to reactivate a market related to many types of industries and jobs; and also for architecture at all its scales. The boom in the international price of agricultural commodities, fundamentally soybeans, along with the influx of foreign exchange for their export, represented a breather (and some Argentinian pesos) for state coffers and citizens’ pockets in the context of an economy that was having to start from scratch. At the same time, the reactivation of consumption took many forms, boosted by the creativity of a population accustomed to economic fluctuations and instabilities. Savings, regardless of their measure, became tangible, with many different forms and moments; they were multiple, varied and unexpected—like life itself.

Any attempt to unify a story that visualizes all the forms that money takes and describes them simultaneously rapidly comes up against the problem of its enormous diversity. But if relating dissimilar objects is fundamentally an architectural exercise, the representation techniques of the discipline are suited to the task, particularly the descriptive geometry techniques developed by Gaspard Monge in the late 18th century and later adopted as the fundamental language of architecture. Monge’s artifice serves to translate any three-dimensional object into a plane using a system of parallel projections that also makes them sufficiently abstract to be perfectly legible, measurable and, therefore, comparable.

In the mid-1930s, using these disciplinary tools, with a similar premise, Ernst Neufert embarked on the monumental task of normalizing all aspects of modern life in his building manuals. With the aim of regulating industrial production and placing architecture in line with and at the service of these processes, his book functioned as its own universe, a selection of the world, absolutely partial and indoctrinating, measured and proportioned according to the human body.

If Neufert’s manual took the body-industry relationship as a reference of modern society; a narrative that describes the multiplicity of forms of money in Argentina requires a selection of specific references that respond to local consumption and economic development. It must illustrate them without hierarchies and allow comparison, without taking the human measure as a unidirectional reference. Their disorderly coexistence in a plane is what allows them to be measured, their interpretation is progressive and scalar, and their starting point is a 100 Argentine peso bill.

This article is part of “You met me at a very strange time in my life,” our CCA c/o Buenos Aires program that investigates architecture during the Argentinian financial crisis.