Poking Holes in Modern Space

Mikio Wakabayashi on the thoughts and actions of Hiroshi Hara

Is Hiroshi Hara a postmodernist?

To foreign visitors of Japan, the best-known example of contemporary Japanese architecture may well be the Umeda Sky Building in Osaka, designed by Hiroshi Hara in 1993. With twin forty-story towers linked at the top by a ring-like Floating Garden Observatory, the structure has attracted throngs of tourists since The Times of London reported its inclusion on the Dorling Kindersley list of “Top 20 Buildings Around The World” in 2008. Visitors may also visit the Kyoto Station Building (1997), the point of arrival for rail lines to Japan’s Kansai region. In its vast concourse, escalators and a grand staircase climb up from a valley-like first floor to a rooftop Sky Garden. Another familiar Hara work is the Sapporo Dome (2001), which resembles a gigantic silver flying saucer. Hara is arguably one of the most prolific and successful architects running small practices in Japan today, having designed such complex yet diverse structures.

Spaces that appear to invert interior and exterior; structural strata that evoke clouds or mountains; elaborate ceiling and window designs the introduce light; exquisitely wrought bird motifs or geometric patterns that bring to mind shadows, clouds, or the wind…some of these characteristics of Hara’s work could suggest that he shares Western postmodernist impulses to embed narrative or symbolic elements in architecture. Indeed, such a critique is often leveled at his work, but such impressionistic criticism does not explain the public acceptance of Hara’s work that persists today.

From the late 1960s to the mid-1970s, Hara wrote a number of philosophical treatises on architectural principles—“porous body” theory, “floating architecture,” and “homogeneous space”—that impacted Japanese architecture practice. He is also known for surveys he conducted from 1970 to 1980 of vernacular settlements in Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and South and Southeast Asia. These reports, published as extra issues of SD (Space Design) magazine from 1973 to 1975,1 and theorized into one hundred teachings for architecture in Kenchiku Bunka magazine in 1987,2 introduced a new system of knowledge to Japan’s architectural milieu.

Hara’s efforts to disseminate and apply both his radical architectural thought and his thorough research on vernacular to his own architectural practice are surely linked on some fundamental level to the positive public response to his works. For this reason, I have misgivings about the superficial interpretations of Hara’s architecture that seem to have become conventional wisdom. Postmodernism does not explain this fundamental link. Hasn’t something been overlooked? What is at the core of this architecture, which may appear postmodernist in some ways, yet which Hara based on his own pioneering theories and surveys?

-

Hara Laboratory, Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo, Dwelling Group, series 1-5, SD magazine, 1973-1979. The same content was later compiled into books, Dwelling Group, Vol. I & II (Tokyo: Kajima Institute Publishing, 2006). According to Hara, the word ‘group’ in the title was incorrect in the mathematical sense and should have been ‘assemblage’ instead. ↩

-

The ideas that Hara gleaned from his village surveys were presented as a collection of architectural theses articulated as a single system of knowledge in Kenchiku Bunka, April 1987, then published in book form as Learning from Villages: 100 Teachings (Tokyo: Shokokusha Publishing Co., 1998). ↩

Inquiries from outside the West

Hara’s office, Atelier Φ, is in a quiet residential neighbourhood not far from Tokyo’s bustling Shibuya Station, currently undergoing massive redevelopment. When we visited, Hara was in the midst of drawing something on a sheet of tracing paper on his worktable. It turned out to be a hand-drawn timeline featuring several dozen influential modern and contemporary politicians, revolutionaries, philosophers, writers, scientists, and technologists—interestingly, there were no architects—and the major events (wars, revolutions, discoveries, technical innovations, etc.) associated with them. Hara explained that he was creating the timeline and rereading a number of texts in response to our questions about postmodernist architecture. For him, an understanding of the figures and ideologies of the twentieth century would allow him to properly appraise postmodernism in the broader context of world history, not merely in the context of architectural history.

As he referred to his timeline, Hara spoke freely of interrogations and critiques of modernity, ranging from criticisms of dialectic thinking and skepticism about electoral democracy and money to reflections upon the similarities and differences between Adorno’s negative dialectic and Buddhist or Japanese thought. While we wanted to explore were the origins of the imposition of postmodernist architecture upon Hara’s work, postmodernist architecture appeared to be a topic outside his sphere of interest. The focus of his thought regarding the modern era never deviated from a critique of “homogeneous space” and the question of how to surmount it.

Hara discussed homogeneous space in detail in a 1975 essay published in the philosophy journal Shiso (Thought).1 In it, he asserts that every civilization or society has a prevailing concept of space, and that the prevailing spatial concept of modern society is of homogeneous space, which eliminates differences in natural conditions and erases historical and cultural meaning. “Universal space,” as epitomized by the sketches of glass skyscrapers by Mies van der Rohe between 1919 and 1921, reified homogeneous space as a spatial concept, making it, Hara says, the victor of modern architecture. Hara argues that, due to the intrusion of homogeneous space as a phenomenon into the non-homogeneous cities and societies of today, we must do away with it if we hope to find true liberation.

Glancing at his timeline from time to time, Hara continued his critiques of homogeneous space as well as of modern thought, science, politics, and economics. He spoke repeatedly of the limits to considering modernism and postmodernism within the confines of Western thought, logic, and culture, citing intellectuals and architects in Europe and North America who remain ignorant of non-Western societies and their thinking. From this discussion, it was clear that Hara’s international surveys of villages and his familiarity with the literature and arts of diverse regions have leavened his experience as a Japanese architect versed in Western scholarship and thought operating in a world of Western-born contemporary architecture.2 This combination of influences provides the intellectual and existential foundation for his critique of both modernism and postmodernism as they originated in the West.

-

Hiroshi Hara, “Space as Culture: Essay on Homogeneous Space,” Shiso (Thought) magazine, August-September 1975; later published under the title “Essay on Homogeneous Space” in Hiroshi Hara, Space: From Function to Modality (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1987). ↩

-

The word “villages” is a translation of “shuraku” which has been used by Hara to signify vernacular settlements that have not undergone modernization. ↩

Village surveys as an experiment for architecture

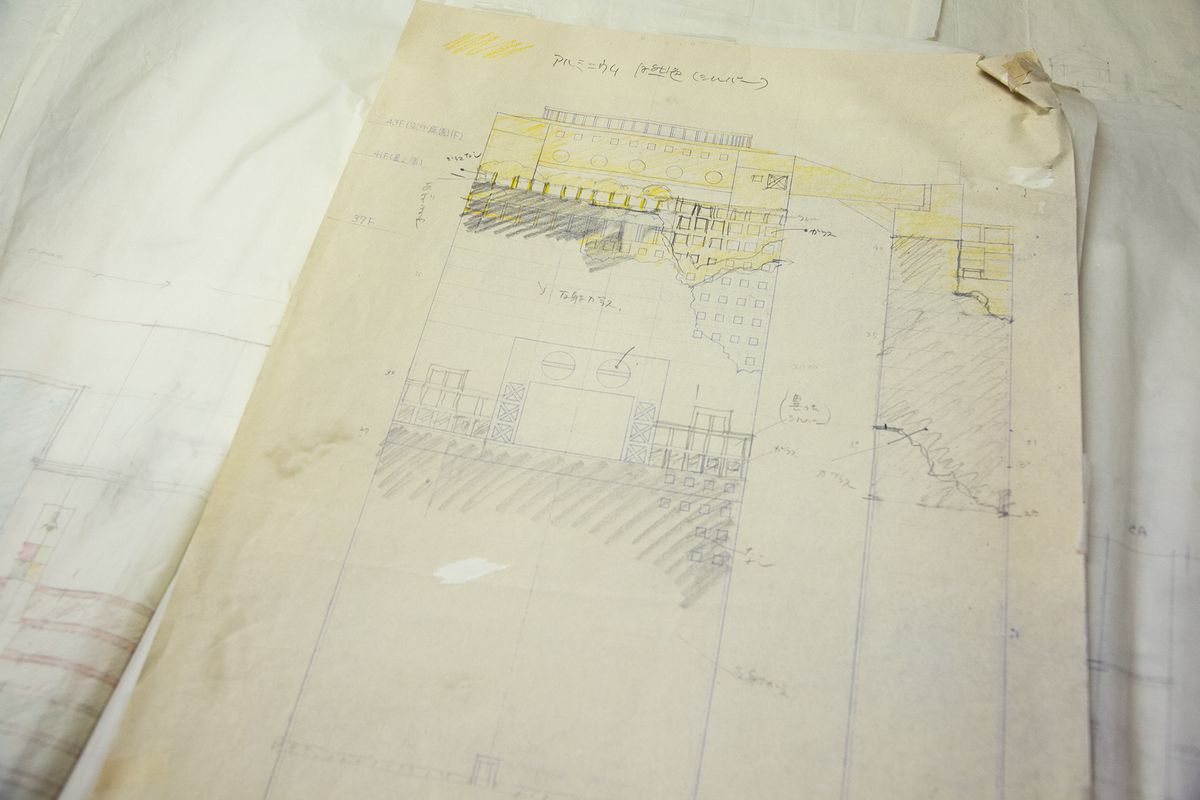

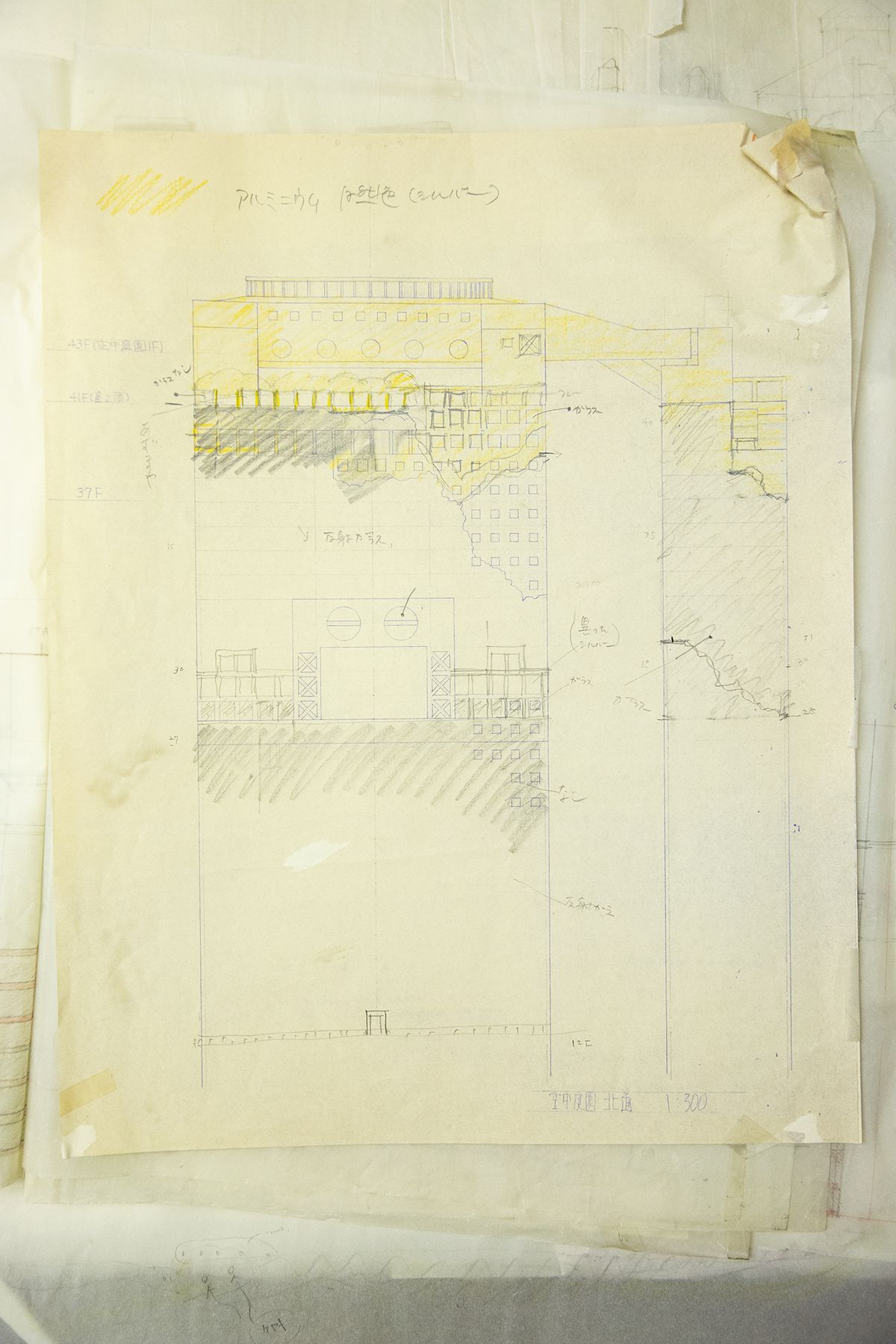

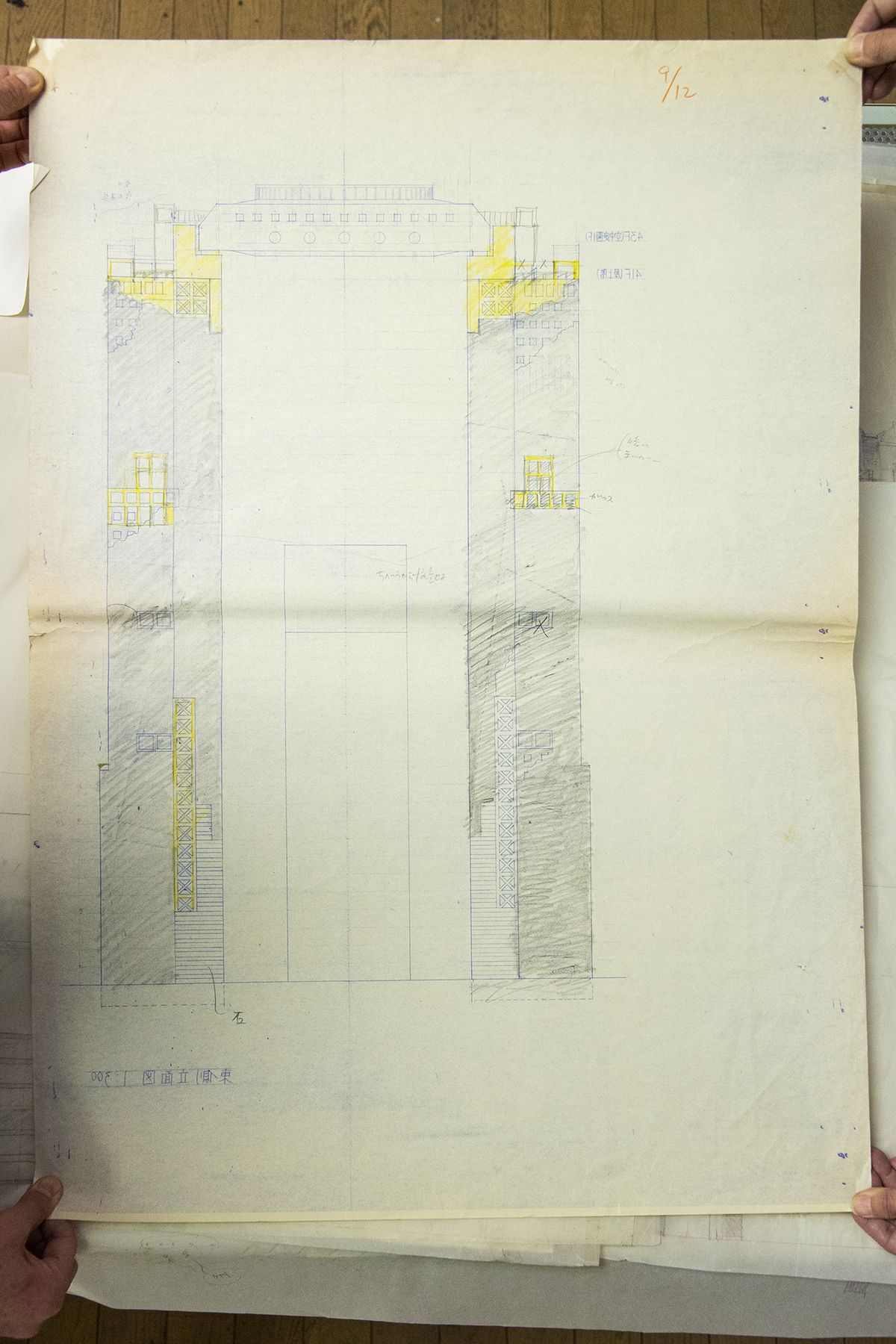

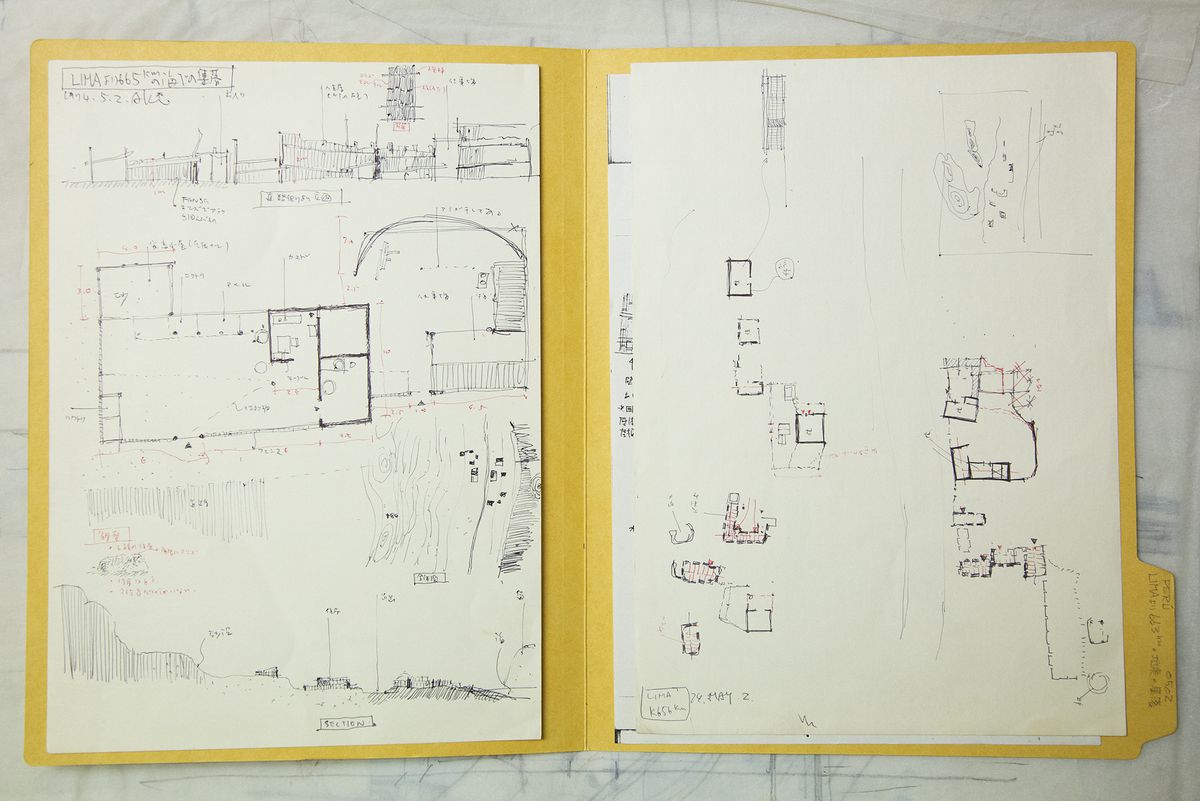

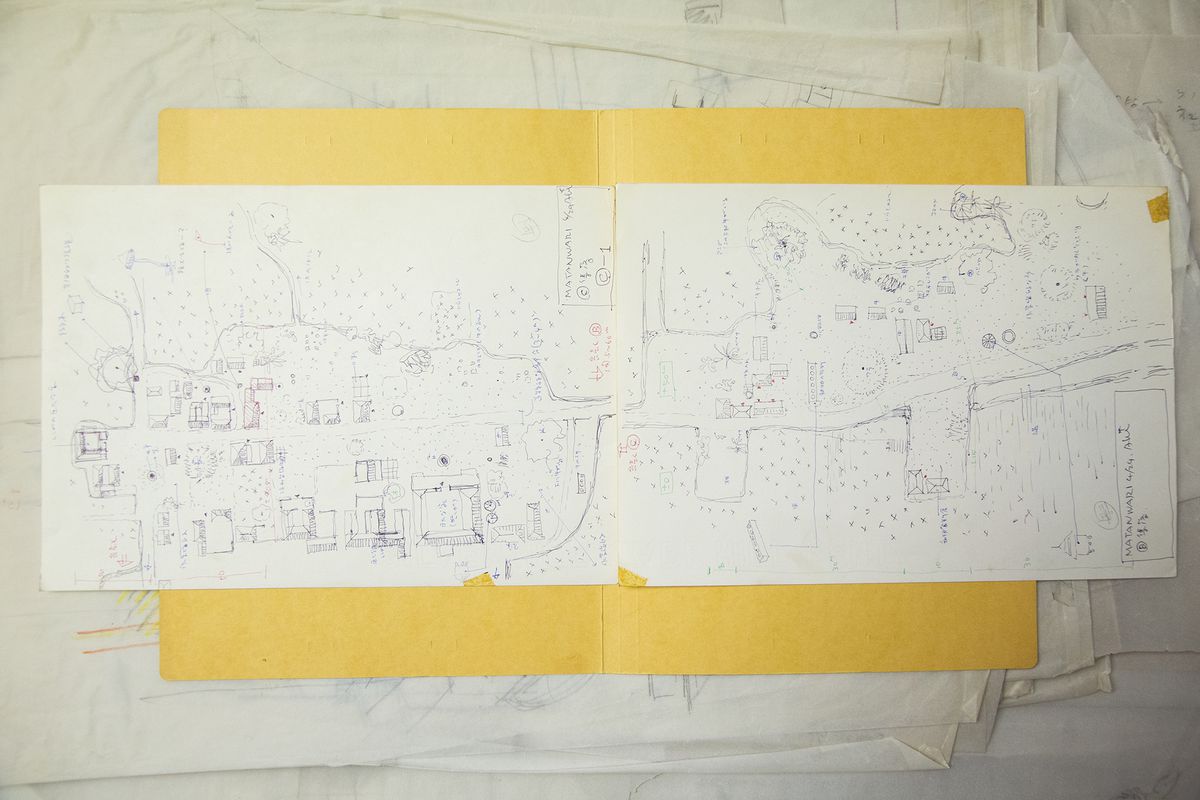

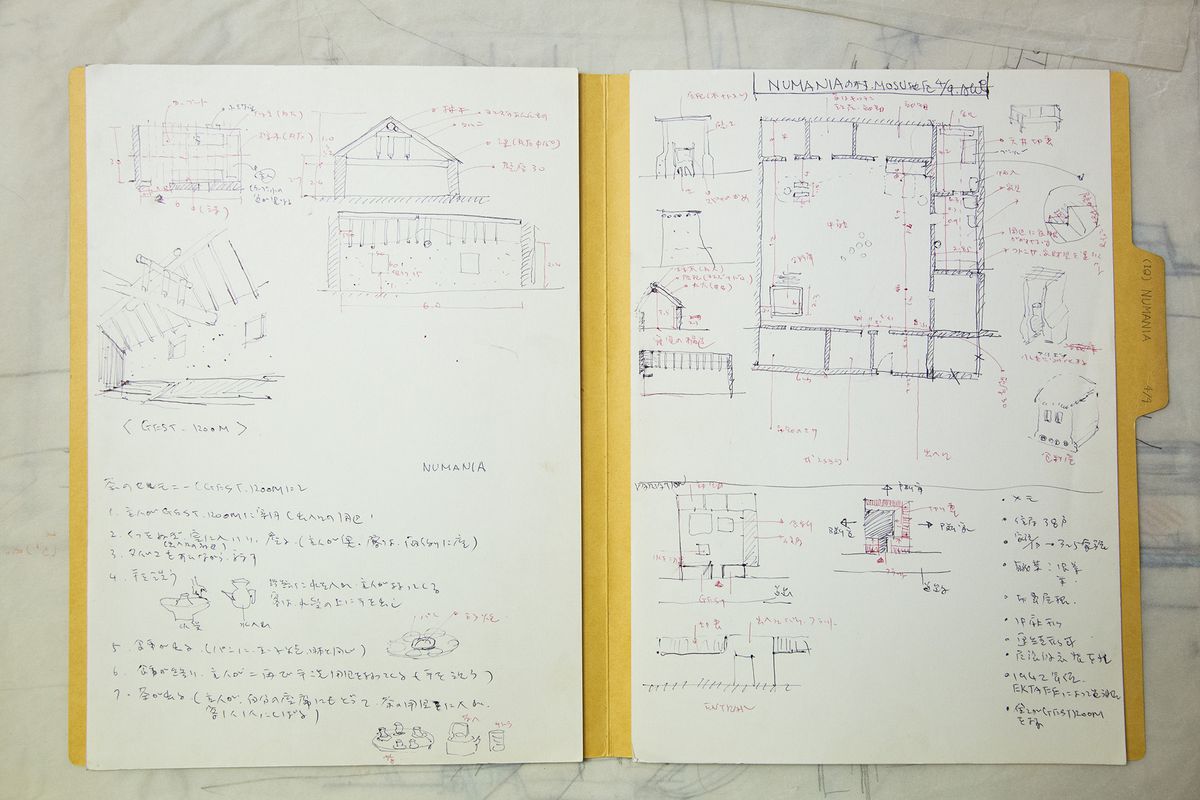

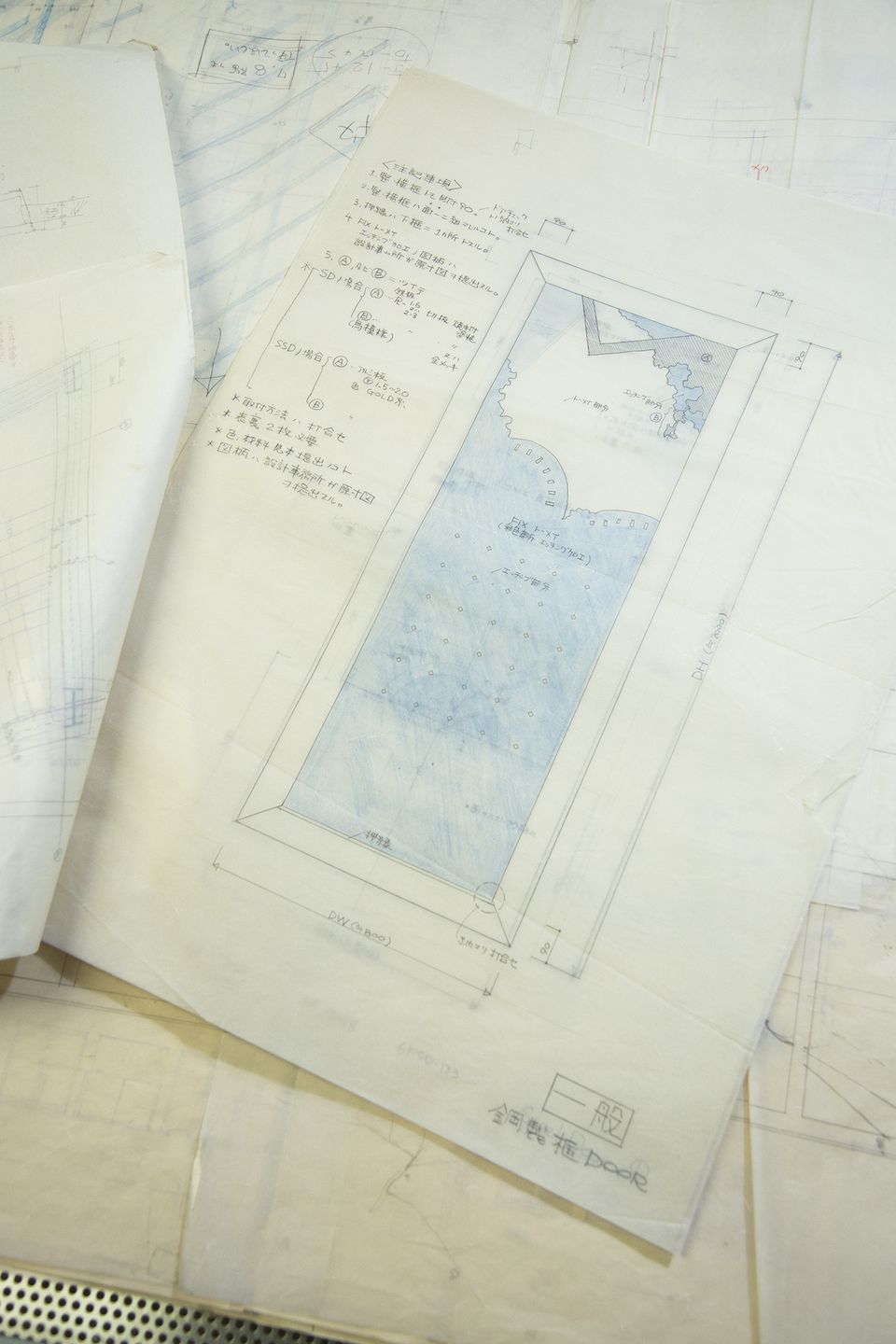

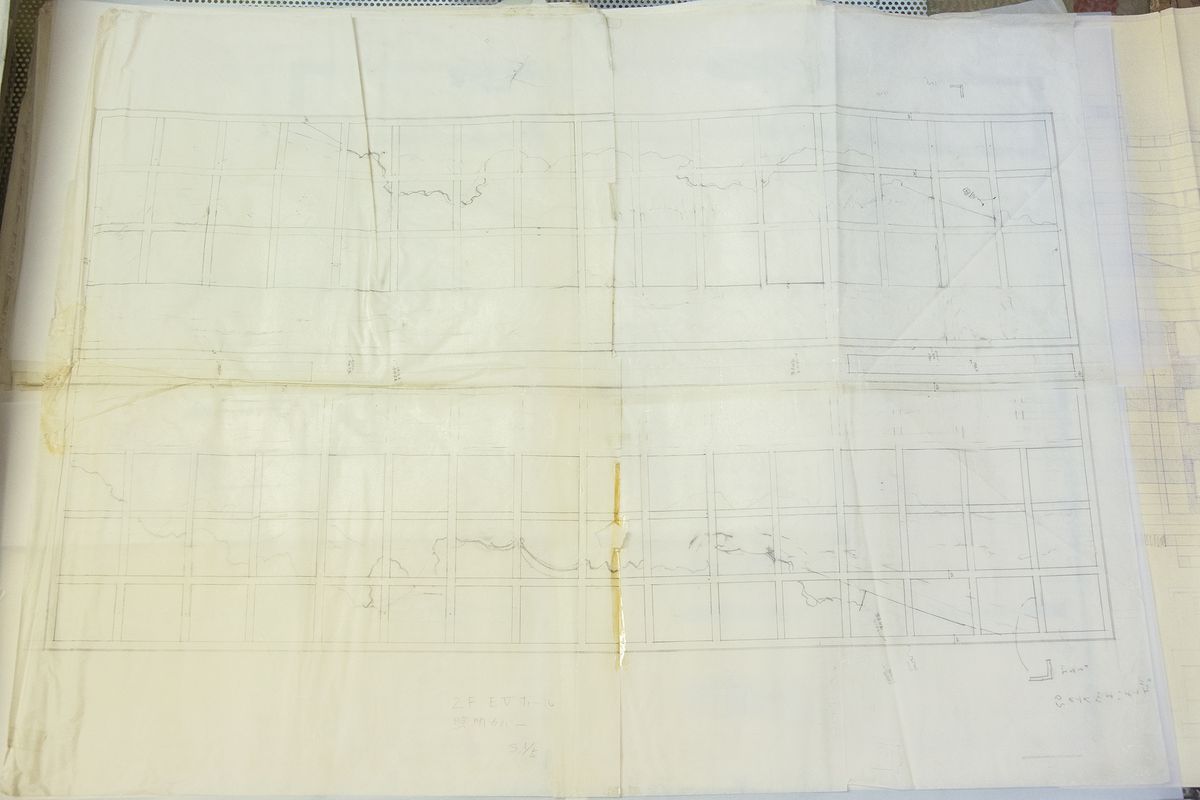

In his atelier, Hara keeps boxes, each identified by a survey’s year and location, containing sketches and notes about each encountered village, its surroundings, the arrangement of its houses, its spatial structure, residential layouts, sectional views, and the design of individual houses’ features. We were astonished at the meticulousness and sheer quantity of these records.

Hara explained to us that in his village surveys, he never selected his destinations in advance, but followed his intuition in choosing which among the villages he came upon along his survey route he would document. Visiting two or three villages each day, he would first try to establish an understanding of his objectives by residents with whom he often could not communicate in words. Then he would survey and rapidly draw maps and sketches of each village and its houses.

Hara’s architectural works following his village surveys reflect the numerous “teachings from villages” that he acquired. With the exception of a few works like Josai Primary School in Naha, in which he incorporated traditional Okinawan architectural motifs, he does not directly quote historical or traditional symbols or designs. As Hara told us, he uses what he discovered through his village surveys to formulate principles, not direct architectural expressions. In this regard, he exhibits a stance toward history, tradition, locality, and culture unlike that of those who confront modernism by referencing or quoting historical or traditional symbols, or by countering universalism with localism or multiculturalism. Hara’s way of looking at the villages diverges from that of theorists like Bernard Rudofsky, who in Architecture Without Architects collected and classified styles and designs of vernacular architecture to posit their heretofore overlooked artistic value and potential contribution to modern architecture.

Through his village surveys, Hara cataloged similarities and commonalities among diverse structures and communities built in places with different environments, histories, and cultures. His staggering research pace of two or three villages a day can no doubt be attributed to this objective to find commonalities rather than to identify the unique and peculiar characteristics of each village. Hara described his village surveys to us as an “experiment” to determine whether architecture “has gone far enough at its present stage, and whether taking it any further would be a mistake.” From this comment, we can surmise that Hara viewed villages as forms produced within distinct environments, and conducted his surveys in order to understand the human imagination that gave birth to these spatial structures and devices. What he was scrutinizing was not the symbolic aspect of villages and their architecture, but the human capacity that made them possible.

In Shuraku eno tabi (Journey to Villages) (1987)1, an account of his village surveys, Hara writes, “Traditional concepts belong not to nationalism, but to internationalism.” In architectural works evocative of indigenous villages or natural landscapes, Hara rejects the international universalist modern architecture aspired to by Mies, Le Corbusier, and Gropius, and searches for an alternative architectural language and space. In this respect, he is a postmodernist. And yet, in the sense that Hara’s architecture is based on “teachings from villages”— international, universal principles he elucidated in the course of his travels to premodern human settlements—he, too, aims for an international, universal architecture, albeit achieved by an approach different from that of the giants of modern architecture.

-

Hiroshi Hara, Shuraku eno tabi (Journey to Villages), Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 1987. ↩

Poking holes in contemporary society

In a discourse on “porous body” theory in his 1967 book What Is Possible in Architecture,1 Hara asserts that architecture is a physical act of opening holes in a closed space. According to Hara, “poking holes” in any manner is a universal and primordial manifestation of the human desire and creative power to shape the world. If we trace his subsequent trajectory we see that Hara sought to identify in villages around the world spatial concepts different from that of homogeneous space; then, applying the principles he discovered, he persistently attempted to “poke holes” in various kinds of space in modern society that are dominantly homogeneous. In the 1980s, Hara declared that without a new spatial concept available to replace homogeneous space, circumstances demanded a strategy of flight during which he would meanwhile create non-homogeneous-spatial architecture at numerous points worldwide. Since then, Hara has persisted in his efforts to elude homogeneous space in a variety of ways.

Tapping into primordial forms of architecture that “poke holes in closed space” and also adopting the “teachings from villages” absorbed through his global surveys, Hara has continued to achieve heretofore unrealized architectural experiences through his work. Visitors to the Umeda Sky Building can see the sky through the hole in the ring formed by the Floating Garden Observatory. People standing in the central concourse of the Kyoto Station Building can see the sky through the glass roof of the atrium, or above the Sky Garden at the top of the escalators and stairs. In Hara’s archives, we found highly detailed ceiling plans among his drawings of works from the 1980s, and views looking upward at ceilings or atriums repeatedly appear in photographs of his works introduced in magazines. Such designs and expressions might be said to serve as narrative devices that guide visitors toward the natural environment or cosmos beyond by perforating a contemporary world dominated by homogeneous space.

-

This was Hara’s first book, published by Gakugei Shorin in 1967. ↩

Mikio Wakabayashi thanks Haruhiko Sunagawa and Yuriya Sumida for their assistance in researching the archives of Hiroshi Hara.

Translation from the original Japanese to English provided by Alan Gleason.

This essay is part of Meanwhile in Japan, a CCA c/o Tokyo project that includes three events in Tokyo, two more forthcoming web essays, and three forthcoming books.

Related article