Sounding Towers

Text by Shannon Mattern

This 2000 photograph from the CCA Collection depicts architect-engineer Vladimir Shukhov’s Shabolovka Radio Tower, commissioned by Lenin, completed in 1922, hailed as a Constructivist icon, and now in dire need of restoration. This photograph might be used to tell the story of Russian constructivist design, or of photographer Richard Pare’s numerous visits to the Soviet Union over the past 20 years to document this and other neglected modernist structures. Yet what we might also discern in this photograph is the presence of something invisible, intangible—an immaterial spatial history that has echoed across the past century. This sturdy hyperboloid structure, now weakened by extensive corrosion, has been the source of evanescent waves of sound that have roused revolutions.

Lenin regarded radio as an invention of tremendous political significance; he likened it to “a newspaper without paper and without wires,” a tool for distributing propaganda far and wide without physical infrastructural encumbrances (and equally well suited to selectively disseminating untraceable messages among comrades). It was the live voice, “the history-making event of its speech in present time,” Susan Buck-Morss writes, “that carried mass-political charisma.”1 While the voice enchanted aurally, the infrastructure that carried it—the electrical grids and radio towers—appealed visually, exploiting a historical connection between the technological sublime and nationalism.

The attention paid to these modern communication architectures foreshadowed our present-day fascination with high-security data centres and the seaside shacks where transoceanic fibre-optic cables come ashore. Yet the marvel of radio technology and its promise to collapse geographic distance didn’t mean that there was no need for, or appeal to, old-fashioned orality: the live, present human voice embodied in its speaker. Buck-Morss acknowledges that, in the age of mass society:

The voice as a means for organizing the masses demanded a new technology. Megaphones magnified sound by directing its focus, but still required the visual presence of the speaker to reach a mass audience at all. Speakers’ podiums recognized this fact, and they were a common design of revolutionary artists in the early years of the Bolshevik regime, even after electronic loudspeakers increased the audio range.2

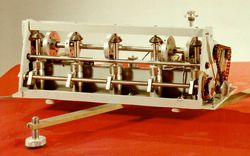

One such podium, also represented in the CCA’s Collection, is El Lissitzky’s “Lenin at the Podium.” In 1920, while the Shabolovka Radio Tower was under construction, Lenin invited his students in Vitebsk to adapt Suprematist methods to real-life needs by designing “a podium on which leaders of the revolution could speak to the people.”3 In 1924 Lissitzky took his student Ilia Chashnik’s design and, for reasons that many scholars have speculated about, added a Lenin figure to the top of the tower4. A version of that figure—Lenin mid-proclamation, in jacket and tie, with outstretched arm and pointed figure—had first appeared in a 1920 poster, “Prizrak brodit po Evrope, prizrak kommunizma” (A Spectre Haunts Europe, the Spectre of Communism).5 Lissitzky later expressed his own satisfaction with the podium design: “it’s just what I wanted, the sweep of the structure emphasizing the gesture,”6 which, here, is a pronounced leaning-forward, if not a dramatic gesture with the arm.

What is also gestured toward here is the sound of the voice. What we see in these two images are constructions that function as sonic infrastructures, supports for vocality. Listening to these mute photographs, and to other drawings and models and artifacts in collections and excavation sites around the world, and also listening for resonances among materials in disparate collections and sites, we can continue to piece together architecture’s history as a sounding medium.

We welcomed Shannon Mattern as a Visiting Scholar in 2012.

Susan Buck-Morss, Dreamworld and Catastrophe: The Passing of Mass Utopia in East and West (Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2002), 137.

Buck-Morss, 137.

Margarita Tupitsyn, El Lissitzky: Beyond the Abstract Cabinet: Photography, Design, Collaboration (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 32.

Tupitsyn, 32.

Victoria E. Bonnell, Iconography of Power: Soviet Political Posters Under Lenin and Stalin (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997), 144.

Tupitsyn, El Lissitzky, 20.