From Within an Ecology of Practice

Francesco Garutti introduces The Things Around Us

The potential for architects and urban planners to be influential and transformative agents of space has been swallowed up by the dominant planning logic of neoliberal urbanism. Often called upon to simply participate in, rather than shape, transformation processes—deploying architecture as “a decorative tool to camouflage the neoconservative politics and economics of urban development”1—the twenty-first-century architect is confined by the rules of an aggressive and uncompromising market and its restrictive, conformist design ideologies. With the possibility of a radical reframing of space now hampered, many architects today find themselves reduced to service providers, asked only to improve the marketability of developers’ projects with surface-level features like well-being and sustainability.

The debate in the discipline between contextualism—the idea that architecture should be derived from its context, be it physical, temporal, or cultural—and autonomy—according to which architecture is an independent aesthetic product—is increasingly irrelevant. Context means something wholly different in today’s increasingly polymorphous, extensive, and globalized urban space. It is therefore perhaps more urgent now than ever for us to redefine the concept and question its use. An updated vocabulary and a new catalogue of tools to analyze global urbanization processes are perhaps good places to start.2 But we also need to recognize and learn from those architects applying these new ideas of context both in and on space.

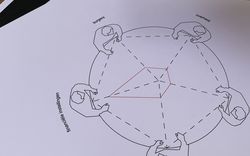

Rural Urban Framework (RUF) and 51N4E, two offices active in what seem distant and distinct geographical areas—a string of rural Chinese villages, the fringe of settlement in Ulaanbaatar, the centre of post-socialist Tirana, and the neglected corners of twenty-first-century Brussels—offer insightful case studies on the role of the architect within the dynamics of planetary urbanization. Attuned to the political and economic forces tied into every project and every site, both offices superimpose large and small scales in their work, rethinking site-specificity along entirely new lines. Together, they complexify the very notion of context in architecture, seeing it as alive, metabolic, and conversational, and moreover, defined by an interwoven network of manifold systems and influences. Context, RUF’s and 51N4E’s work suggests, overwhelms us into abandoning our posts. And in this expanded definition, it forces us to rethink what it means to practice architecture.

-

Teddy Cruz, “Rethinking Urban Growth: It’s About Inequality, Stupid,” in Uneven Growth: Tactical Urbanism for Expanding Megacities, ed. Pedro Gadanho (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2014), 51. ↩

-

Christian Schmid et al., “Towards a new vocabulary of urbanisation processes: A comparative approach,” Urban Studies 55, no. 1 (2018): 19–52. ↩

In different ways and at different speeds, RUF and 51N4E formed and evolved as living, collective organisms, each absorbing and exploring a range of territories over the years and continually hybridizing research and design. For both, the office metamorphosis began as a physical journey, a process of shifting vantage or of reading the landscape. In 2004, Freek Persyn and Johan Anrys of 51N4E took their first trip to Tirana, marking both the beginning of a decade of research and design work in Albania and the launch of an integrated, on-site laboratory. Likewise, in 2005, John Lin and Joshua Bolchover of RUF travelled from Hong Kong to a project site through the provinces of Guangdong and Guanxi, sparking their first study of the composite, transitional territories linking the urban and rural in southern China. The journey, for RUF and 51N4E, is not simply a worn-out metaphor for a cognitive experience; it is also a physical state in which frictions and overlaps between geopolitical forces, legislative anomalies, environmental situations, and economic and social contradictions redefine every assumption about how to practice architecture. For both offices, the journey is an act of careful observation and listening, an attempt to understand and to adopt and adapt practical and ideological tools. It is an approach that absorbs and incorporates different methodologies according to changing constraints, and one that listens for new voices.

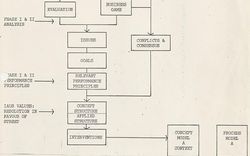

Back in 2006, when architects and researchers in China were still focused on the study and development of the megalopolis, Lin and Bolchover began to explore the processes of urbanization from another perspective. Crossing the Chinese countryside to study hybrid city-countryside geographies and forms of settlement, they identified the terrain of their work in the contradictory manifestations of the accepted rural-urban dichotomy. This gave rise to RUF as an independent laboratory embedded in the University of Hong Kong. Lin and Bolchover thus delimited their field of work to places where small-scale instances of architecture and the built environment testify, as evidence, to large-scale policy shift and social change.

Around the same time, 51N4E won a significant competition for the construction of a tower building in the heart of Tirana. Caught between worldviews and population shifts, between its historical isolation and its recent openness to the global market, Tirana was the heart of what was then the youngest post-socialist democracy in Europe, yearning for ideas and desires that could redefine its political and social identity. The competition and the TID Tower that 51N4E designed in response gave rise to an extended landscape of new projects and research in Albania, launching a twelve-year chapter in the office’s history that would go on to transform its methodologies. Working with the uncertainty of political reconstruction, a new class of leaders, and a precarious, fragile economy, the office underwent a conceptual and structural metamorphosis during its time in Albania that the architects brought back with them to Brussels. Tirana was a testing ground where the very idea of the design process shifted, absorbing unpredictability, dialogue, and friction, and where empathy, a strategic capacity of engagement with the communities, and a mutual sense of trust between players were the most necessary ingredients.

Both offices, therefore, through different strategies and learning from distant geographical contexts, absorb and incorporate a wealth of actors, alliances, and collaborations that expand the architects’ ecological system, significantly redefining their tools and position. The building itself, in this new ecology of practice, is now more than ever just one piece of an extended system—the final outcome of a long sequence of actions undertaken in the transformation of a territory by a web of agents. But it is also a mechanism designed to resolve—or rather, to reveal—the conflicts, anomalies, and contradictions intrinsic to a new, expanded definition of context. Decomposed, dissected, and reassembled, context—the people, tools, policies, economies, times, and scales with which the architect interacts—not only generates the conditions within which to work, but is in fact the place itself in which and with which to operate.

In what way, then, is the work of RUF and 51N4E specifically useful to reflect on the state of practice and on the transformations taking place within architectural practice? RUF and 51N4E work in environments where conventional relationships between context and building, urban and rural, and temporary and permanent disintegrate, and where economic and social models dramatically shift in a few short decades. Their sites are territories of uncertainty, where it is difficult to decipher what the architect can control. In some cases, these sites are places where the profession itself does not exist.

How do we design public space in a city like Tirana, where for decades a totalitarian regime stifled the very notion of private? How do we imagine sustainable living in a city like Ulaanbaatar, devastated by coal pollution, where new residents in nomadic housing types make up 20 percent of the population? How do we reconceive the identities and spaces of the Chinese countryside, forgotten and excluded for centuries by social reforms and now quickly melding with the urban? How do we return the fragments of Brussels’s failed utopian World Trade Center to the city?

Questions like these invite us to not only return to the archetypal problems of space production—what we designate as public or private, how we treat the air or light, how we define place—but to experiment with the present. In this present moment, the tools needed to answer these questions cannot simply be limited to the physical, material strategy of building. The answers must include the very elements that define context in its broadest form—people and institutions, economies and identities, charities and funding providers, politicians and clients, infrastructure and markets, crops and livestock, local technologies and global materials. If context is an assembly of things and agencies1—itself simultaneously a site and an instrument of that site’s transformation—it is crucial to position the role of the architect as just one player within this refined ecology.

As both insiders and outsiders, the architects of RUF and 51N4E act in turn as builders, planners, entrepreneurs, activists, community organizers, and policymakers. They are directors and activists, choreographers of relationships and conditions, and, from their liminal vantages, careful observers of what cannot—and, as their work shows, should not—be controlled. Taking this decentralized and dynamic position, the two offices provide a disciplinary reflection on the role of the architect as author. What they offer, in the face of a new, complex, and urbanized context, is a case for the radical power of an ethics of weakness. To redesign our present, ultimately, we have to be able to listen, observe, and strategically incorporate, absorb, and enable other actors’ points of view. Only then does the building that emerges reflect what context means today, and only then does it meaningfully contribute to context’s transformation.

-

See Bruno Latour, “From Realpolitik to Dingpolitik or How to Make Things Public,” in Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, eds. Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (Karlsruhe & Cambridge, MA: ZKM and The MIT Press, 2005), 14–43. ↩

Francesco Garutti curates The Things Around Us: 51N4E and Rural Urban Framework.