Building Narratives

Rozana Montiel speaks to Kim Courrèges and Felipe de Ferrari of Plan Común about social projects, common sense, and building with trust

- PC

- Can you introduce your practice and its specificities: attitude, framework, specific approach, methods, procedures or protocols?

- RM

- One of the most important things about what we do at the office—that we start with—is we try to transform space into place. I believe that space is abstract, whereas place is where you create relationships; where you engage with people. Space is there, but when you build a place, you change the meaning of what you’re building because you engage with people. I always say that I like to work with the people and not for the people. It’s just a difference of one word, but it completely changes the dynamic of how you relate to someone. Architecture is not only building with bricks; it is also a social construction.

Architecture today is not done by only one person, but rather it’s many people that work on a project that produces a result, and we have to work with different disciplines in order to achieve that. I work with photographers, with writers, with filmmakers, with anthropologists. Their feedback is really important to us, and we really work as a workshop in this way. Every time we start a project, everybody comes in with different ideas, references; we try to work with references that are not only architectonic.

Our process begins with research, and with talking about ideas in this way. Research is always giving feedback to our work, and so I’m always in search of grants that make this possible: at the moment I have a grant from the Mexican government for three years called Sistema Nacional de Creadores, which is so important. I’m always looking for grants in parallel to the design work that we do, so that we can have this process to developing ideas. I’m always trying to find new ideas to develop in research that can then come to light in any given project. Before COVID-19, we were actually preparing an exhibition of the studio’s work at Museo San Ildefonso in Mexico City, but of course it had to be cancelled. We always think about exhibitions as a chance not only to show our work, but to prepare an installation reflecting on work that we have done.

- PC

- What about social and communitarian projects? Can you summarize your strategic approach on this matter, and perhaps introduce one of them?

- RM

- Another focus of the studio’s is to work on social projects, and not only in private work. I think as architects we really have the responsibility of working on social projects. I believe in design, in general, so it doesn’t matter if it’s a big project starting the territory or if it’s a very, very small project. I like to zoom out and zoom in all the time; going from different scales and layers; from the object and the artifact and the book to the scale of the city. In doing this, we always try to give more, too. One of the most important things for architects to do is to listen; listen carefully, and then we act. We work with people asking us for something and we always try to give them much more than that.

For example: we were recently asked to design just a roof—and we gave them a whole community centre. This was in Veracruz, on the Gulf of Mexico, where the weather is very warm; where you cannot do anything without a roof. The area had many underused spaces but with a lot of potential if they had roofs. This was an underused space that was supposed to be a basketball court, but it didn’t have light at night and you couldn’t play during the day because it was too hot to do anything.

On top of this, the vegetation in Veracruz is amazing: it grows so fast if given the right conditions in that humidity. So, they asked us to put in a roof and we thought, how do we give them more than just a roof? This is an amazing space to become almost a community center. What we did was simply leave more room in between the columns of the roof for program; making the roof higher; adding a second level. This created room for classrooms, a small library, a gym, and a garden. They hadn’t initially given us the space for a garden, but when they saw our plan, they gave us that area to work with as well and now that space is habitable because of the vegetation and shadow. So simple.

- RM

- Since then, they have even invited a botanical person to create a medicinal area for plants, where old ladies go and make requests; engaging the community. Kids who were just roaming the streets without much to do but get into violence now have a place to spend their days.

Being there and seeing how it was activated was amazing. To see how these kids were there all day playing basketball, playing soccer, going to the library, reading, going into the area of gym in the forum. And this was all because of a strategy that used thinner columns and more space for program. Now, obviously, this costs a little more—but not that much more. It’s a question of making everything useful. Then, even if a developer needs to invest a little money at the beginning, they will get back much more. This shift in perception could make real change. This idea of perception and way of looking is also so important to me: looking closer, looking at details.

- PC

- Which are the most effective representation tools within your practice? Which are the formats of communication and relationship you think are the most effective to conduct social projects?

- RM

- We are also redrawing constantly in the office as a way of looking closer and picking up on details that might be crucial to transforming reality. I always call this an active gaze; la mirada activa. This then becomes a haptic or peripheral sight that I call the eyes of architecture: not only seeing through the eyes, but also seeing through the skin, as Juhani Pallasmaa says.

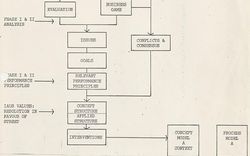

And after this observation, how are you going to tell the story of a project? The mediums of representation are integral to the design process that we do. We usually work in this way that is half on paper, and then as we begin to collect references, we create a board that we are adding to all the time—whether as an office of five or of twenty, as how many people are with the office changes all the time based on projects.

Within this process, we had been using the idea of the post-it note, which became a methodology of sorts, which then became a book. We wanted to do a book about these processes, but that wasn’t just about these projects—so instead, we made a book about the post-its. (Of course, this process was before things moved to Zoom!).

- PC

- We are curious about the context and conditions in which you operate and your own understanding of the notion of common sense.

- RM

- I think that common sense is using what you have; using local materials; working low cost and with minimal resources. If we take sustainability, for example, this is a word that is difficult for me to define because it has become a trend in a way: everything has to be “sustainable.” But I believe that sustainability is about common sense. It’s about logic. It’s about understanding what you have. That’s nature. For example, how are you going to place a house. You need to understand the site, you need to understand where the wind comes from, where the sun enters, where the light comes. These are the things that are existing, that are there no matter what.

For another book that we did recently, titled Common Spaces in Housing Units, we created a manifesto reflecting on all of what we do at the studio. And one point was to seek content in context. Before we set out the design that we do, we researched the specific potential resources and community assets and the essential needs of a site. We hire locally, we serve regionally, we work with the community, not just for it—we engage with people not as consumers of space, but as place makers.

Now, we are working in different type of contexts in Mexico, so we work in marginal sites, with informality and in peripheries. And we find rich information in this context, which relates to what I was speaking about before in terms of sustainability; using the existing logic of a place. Our thoughts become actions, and our actions become habits: changing a social context or a thought; this changes actions and leads to real evolution.

- RM

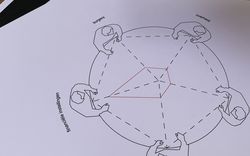

- We’ve also created this idea Situ-actions, which are site actions. The idea of these site actions is that there are urban actions that are very low-cost interventions that involve people in their space in ludic, innovative way. And the purpose is to get people to voice their needs and to understand their aspirations and what they want. Once there are many of these small tactics, they create a strategy and this strategy leads to change.

At first, it’s hard for people to believe that these small interventions are architecture. It can be very difficult to convince all the stakeholders and all the institutions, for example, how important this is. But I believe in this, and I believe that beauty is a basic right. And that this doesn’t have to cost a lot.

The other day, someone was asking me what luxury means to you, and I said, well, I think luxury is it’s having a dignified space. It doesn’t matter the cost. It’s not putting more money on it. It’s been really interesting to try and show developers that this doesn’t have to cost more, and that this will change people’s perceptions and lives long into the future.

- PC

- Court/Cancha is not the only project commissioned by Instituto del Fondo Nacional de la Vivienda para los Trabajadores (INFONAVIT), right?

- RM

- Exactly, there is also Common-Unity and Fresnillo Playground. When we began to work on Common Unity (Común-Unidad) they didn’t let us go in. They said—people always come in and say they are going to rehabilitate this space and it never happens. So, we approached the site to learn about the context, and to gain the people’s trust. We went in saying we were sociologists of the university across the street—which I don’t think is a lie! We are architects, and we are also sociologists. We started talking with people and crating map queries. But instead of approaching it in a top down, quantitative way, we approached it in a qualitative way. Instead of, “how many lights do you have, do your children go to school, do you have a computer,” we took a different approach. We asked, “where did you have your first kiss?” “Where do you go to soke cigarettes,” to really learn about people, earn trust, and listen.

From there, they were involved in the process. It began as a really gated yet insecure space. They initially said that whatever we did, we could not touch these gates. But after involving them in the project and showing them what different spaces might be possible, in the end the neighbors were taking out 90 percent of the gates themselves—we didn’t even have to, because we had changed this sense of a barrier. We replaced vertical dividing structures with protective horizontal structures: we listened to their requests for roofs above all else, but implemented a diverse program within that with their trust.

The space completely changed, people couldn’t believe it: they said, no, this is for rich people. They couldn’t believe that it didn’t cost more, because we so often feel we don’t deserve these beautiful spaces. It was really interesting to see how they started feeling ownership; they started feeling that it was their place to be. This perception of the people of their own space. We called it Common Unity because it was first separate units, separated because of insecurity, and it again became a community. I think a lot about how we name projects, too.

This conversation is the third of a series of interviews conducted by Plan Común that unfold both on this website and in video in the audiovisual archive OnArchitecture.