An Ethical Real Estate Project

Kim Courrèges and Felipe de Ferrari of Plan Común speak with Jack Self of REAL about a society more equal in all dimensions

The Practice as Project

- PC

- Can you introduce your practice and its specificities—its form and framework and your attitude and specific approach?

- JS

- The Real Estate Architecture Laboratory, also called REAL, is a foundation dedicated to promoting democracy, inclusivity, and equalities of many kinds, among them racial, class-based, wealth, and spatial. In the United Kingdom, the foundation structure means that we have what are called articles of association, kind of like a constitution, which is established at the beginning and which regulates what the company can and cannot do.

In practical application, what this means is that it’s very difficult for us to take on a lot of architectural work because, for example, a private villa in the Mediterranean probably does not meet the criteria of promoting democracy, inclusivity, and equality. And the structure of REAL itself means that I, as its director, don’t get to decide if it does; there is an independent board of advisors who determine which projects follow our mission and which do not. In terms of our activities, we therefore work mainly on cultural projects—although for the last seven years we have been pursuing a housing company of our own, now recently launched.

- PC

- Are there concepts recurrent in your daily work that could be relevant to understanding your approach to REAL?

- JS

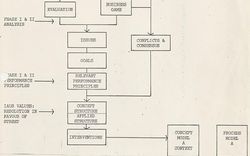

- What we’re trying to do is to focus first on a material analysis of the present—on the “real”—and to understand the potential for the architect to intervene in that material. Ironically, although we mostly work on cultural projects at the moment, our dream is to make objects that are buildings—let’s say, spatial objects. We sit within a long tradition of Marxist materialism or feminist materialism, and many other concepts of material analysis.

We didn’t invent the phrase “form follows finance,” but we did do a lot to popularize it in the late 2000s. This phrase is a recognition of the fact that all power in society today stems from economic power; all forms of political management are in fact extensions of the economic realm. Therefore, you cannot have any agency in society unless you are very precise about how you intend to engage with the sphere of economics.

In practical terms, what this means is a couple of things. The first is that we are always working backwards from the economic conditions that we find ourselves in. We start from a particular financial condition and a particular financial objective, and we design entirely inside those parameters to create something that the system didn’t want to create. It’s a way of trying to pervert or overturn current systems of capitalism by forcing capitalism to be consistent at times when it doesn’t want to be.

- PC

- How dependent is REAL on you?

- JS

- The best way to answer that is to say this: twelve years ago, I was living in social housing in South London, and I couldn’t afford to catch the bus and I couldn’t afford gas for a hot shower. I had no money and no access to money. I had some cultural capital, but very little. And the question was: how am I going to execute the projects that I have in mind? How do I get to a position where someone will give me a large amount of capital to do something very different from what exists?

What I understood is that society still sees the practice of architecture mainly through the individual. This is changing—for example, it was a huge moment when Herzog and de Meuron won the Pritzker Prize; it was the first time it had ever been given to two architects. As time has gone on, we have come to understand architecture more and more as a collective practice, but this was not the case in 2009. So, the project that I pursued was to use myself as a construct of social and public figure to gain the type of social and cultural capital necessary to advance my ambitions and then, at a critical moment, transfer that power or transfer that capital into two things. One is actual capital, because I’m interested in money, not in being cool. And the other is to then transfer that power away from me and into a diffuse group. I believe we are at the end of what I would call the Jack Self project.

- PC

- Let’s continue with your goals on the question of housing.

- JS

- My objective has always been very clear—to create a society in every possible way more equal. And particularly I’m interested in that from the perspective of housing. What I have noticed is that high-quality, affordable, secure, and stable housing is a precondition for democracy and for many other types of equality—gender equality, socioeconomic equality. All of these will come from a good housing situation, I believe.

When I work with other designers, they often try to show their individuality and their personal expression. And I always say, how can we make it more normal? How can we do something which is so normal that it maybe doesn’t even look like an architect was involved? Of course, that has economic benefits as well, as the more you are able to work with ideas of universality and normality, the less expensive your architecture tends to be.

For example, I often see a family from Ethiopia occupying a 1970s social housing apartment in London, and the design and aesthetic—the relationship of the rooms—is completely inappropriate for the cultural structure of that family. We need to understand how to design architecture which does not make a preference for cultural background or family structure. At a financial level this also has to do with creating buildings which can last for a very long period of time. How could we design a building to last five hundred years when we have no knowledge of the society, the economic and political paradigms, or even what their concept of family will be?

Understanding Context

- PC

- Could you introduce the specific framework of REAL Homes and the tactics behind it?

- JS

- There are many contradictions within this project. However, if I were to pitch it to you: REAL Homes is the first ethical housing product, and a key invention in the ownership revolution.

What do we mean by this? At the moment there is no such thing as ethical real estate, however in the next ten years we are going to see two very important factors emerge. The first is the largest transfer of wealth between generations in the history of humanity: sixty trillion dollars will be passed from baby boomers to millennials. Millennials are what you could call the first “woke” generation, and they have very different social attitudes and values to previous generations. Millennials are the first generation who prefer to identify as socialists than capitalists. They are the first generation to talk about racial inequality in a serious way. They are the first generation for whom LGBTQI+ rights are not even a controversial question; that’s just a fact of society. So, when this money is transferred, I think we will see a really significant shift in what society looks like.

The second thing is that since 2000 we are seeing more than a one thousand percent increase in what’s called “social impact capital.” This refers to investment funds who are looking for three categories of investment: environmental investment, so perhaps in renewable energy technologies or other types of climate-related investment; social; and governance. So, we have a huge amount of money which is about to arrive in this realm, or is already arriving, and looking for alternatives to the status quo in some form. But only five percent of social impact money is being used to make buildings because there are no ethical real estate products.

REAL Homes is basically asking, can we group all of the various ambitions that we have under this concept of ethical real estate—which is carbon neutral to build and carbon neutral to operate, through a number of different factors including mass timber construction, and modular and prefabricated technologies. It is a model based on a means-tested or what we would call a pay-what-you-can idea of affordability, which means that everyone in the building pays twenty-eight to thirty-three percent of their take home pay. This means that whether you are earning one hundred thousand pounds or thirty thousand pounds, it will always be affordable for you. This also creates socioeconomic diversity within the buildings, and there are systems of governance to do with representation which promote community.

In addition to paying an always-affordable amount of rent, there is also the ability to buy shares in the building that you live in. This is basically like a savings scheme. What we’ve shown is that a mortgage is actually a very bad financial investment. The aspiration to private ownership of this kind is not a good financial decision—and it’s not a good moral decision either. What we offer instead in this case, since everyone in the building is paying rent, is that the shares in the building pay an annual dividend. What this also means is that at the end of thirty years, fifty percent of the building belongs to the people who live there, and fifty percent of the building belongs to REAL Homes. It may be in the future that we push this even further so that it is truly cooperative or collective: at the moment, the reason for fifty-fifty is so that REAL Homes can use that as an asset in order to build more housing. The overall ambition is that by the year 2030, we will have somewhere between three hundred and five hundred buildings within a global network.

- PC

- Do you recognize conflicts in dealing with global capital in this way? How do you balance your convictions and contradictions on the subject?

- JS

- When I talk about things like “ethical real estate,” let’s be very clear: all property is unethical. It is immoral. It is just wrong that humans think that they can own anything. However, I have to speak to capitalists and therefore the idea of ethical capital and particularly ethical real estate is a concept which they can understand. Part of the innovation of REAL Homes is designing its financial model.

Recently with Real Review—the second primary project of REAL Foundation; our contemporary culture magazine—we speculated on the idea of the new renaissance. It’s important to understand the Renaissance as a transitional period. The Renaissance existed between the Medieval and modernity: it was not an end point, no one wants to live in the Renaissance forever. So, the renaissance that we’re experiencing now also requires transitional commodities. And what this means is that in order to get to enough scale, in order to have enough impact, we will need to work with certain models of capitalism. But in the same way that the feudal lords started paying merchants to engage in commerce and those merchants then destroyed the feudal system, my hope is that by engaging with a certain type of capitalist, in twenty or thirty years we will be in a position where we will no longer need those capitalists and in fact, we will have used them to create a different system.

That having been said, I’m also very realistic that REAL Homes is not a global solution to all our problems, or maybe even any of them. But if we are to survive as a species, we will need to fundamentally change the way that we relate to the planet, the way that we relate to each other, and therefore our systems of ownership and systems of housing. What I’m really interested in is a transitional commodity. It is not a solution to capitalism; it is a transitional product which exists between two paradigms.

REAL, Real Review, a contemporary culture review that tracks the ever-changing zeitgeist through its “current moods” Screenshot of website

- PC

- Could you speak more on the many hats you wear related to your approach and strategies?

- JS

- I think the best way to describe this is to make a distinction between architecture as a practice and architecture as a discipline.

Mark Cousins, who was a professor of history at the Architectural Association and who recently passed away, used to argue that people would say that architecture begins in ancient Greece or ancient Egypt or some other point in history, but that really you cannot have architecture until you have the architect. He would say that this means that architecture is mainly either a fifteenth century invention, which I think is more traditionally accepted, or even a nineteenth century invention at the moment at which we start to see the legal frameworks for the profession emerge. It’s quite a recent concept.

But architecture as a practice? In a contemporary sense, it means that architects work with both material and immaterial information and objects. When I think that I’m working as an architect, I mainly think that I’m working as an arranger of different materials, as a composer of some kind. I’m not responsible for every aspect, but I am responsible for their arrangement.

As a discipline, it’s entirely different. I’m registered with the architect’s registry board and I pay my fees and I pay my insurance and I have a legal framework which I then must work within. And to be very clear, that is architecture: this expanded notion of the architect as an arranger is kind of a fantasy. The reality is that architects work within a legal profession that is responsible for the design, management, and execution of buildings. That’s it. Everything beyond that is open to some question. You know, I always call myself an architect and I’m very proud to be an architect. But I also know that I’m not really working as an architect when I’m doing these things we are discussing—this is architecture-inspired activity.

Building a Case

- PC

- Tell us more about your specific role in the organizational model at REAL. Have you developed tactics to appropriate from corporate forms of organization?

- JS

- The role that I will have within the REAL Foundation will be creative director, and creative director is a term that really comes from advertising and is someone who’s responsible for things like a brand’s definition and communication, but also product design and various other aspects of administration. The reason I’m interested in creative direction is because in the world of fashion, for example, you can have a fashion house—even one which has a big name like Balenciaga or Dior—and the creative director is not Balenciaga or Dior. The creative director can be anyone, and the creative director is able then to move within an existing framework.

In architecture, I would argue that Rem Koolhaas was probably the first creative director, because he is not a designer, and he is not an architect in a literal sense—but he is a director. It’s something I would like to see more of in the world of architecture, for the simple reason that in the world of fashion, you can be someone like Nicolas Ghesquière, who graduated from university and at age twenty-five became the creative director of a huge French fashion house like Balenciaga. In the world of architecture, why is it not the case that you can graduate from university and within four or five years become the creative director of something like Gensler or SOM or KPF? What would it mean for these huge firms to actually utilize young talent and young energy and young vision rather than employ the system that we see, within which you can only become responsible for architecture after you’ve spent forty years struggling with toilets and car parks?

- PC

- To use the metaphor “surfing the wave” in 2021 is at best controversial. From your point of view, what might be an alternate image or metaphor to dismantle and replace this one?

- JS

- First of all, I think we should understand what the metaphor of the wave itself really means, because it’s mainly a question of timing and inertia. I was lucky to grow up in Australia where I was able to learn to surf, and the wave has its own power and force, which is many multiples more than the individual. You have no ability whatsoever to control the wave. That’s the first thing. The second thing is that whether you successfully catch the wave or not depends entirely on your point in space at a particular time. If the inertia of the wave catches you, it will continue to move you forward with no effort of your own.

But let’s think for one second, not from the position of the hero, but from the position of someone who misses the wave. It has nothing to do with the skill or the talent or the ability of that person; it has everything to do with their location and time and space. And what I see now is that every generation of architects since the 1990s has been less powerful and has had less possibility and agency than the one before it. If you go back to the 1970s, you had architects in their mid-twenties doing things like the Pompidou Center. Even in the 1990s, you had architects perhaps in their thirties and forties who were doing things like the National Library of France. By the 2010s you do not have any architects in their thirties doing any significant commissions with maybe one or two exceptions in the world. It has been difficult for our generation in the post-2008 landscape to make firms for ourselves. It will be even harder for those people who are graduating now after the pandemic. In this sense, we can say that the wave has passed us. The wave of global capital has passed most architectural generations by.

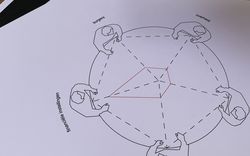

I don’t know what the next metaphor is. Perhaps something more like an ant colony; a display of emergent intelligence that at its basic level is a communistic and communitarian approach. I would argue that the basis for all ideas of what the future of architecture should be rests on the formation of strong community and strong solidarity, and also a removal of the ego which marked previous generations in order to truly cooperate together. And I think we are starting to see new models around that, and I hope that they will continue to get stronger.

I think the objectives are clear, which are to work toward a discipline which is more egalitarian, and that ultimately means mutual support, mutual aid, and cooperation. We cannot keep judging architects based on whether or not they were at the front of the wave.

This conversation is the fourth of a series of interviews conducted by Plan Común that unfold both on this website and in video in the audiovisual archive OnArchitecture.