Working with Energy

Kim Courrèges and Felipe de Ferrari of Plan Común speak with Ignacio García Partarrieu and Arturo Scheidegger of Umwelt about neoliberalism, hydroelectric dams, and designing at the scale of infrastructure

The Practice as Project

- FdF

- Introduce yourselves. What is your practice like, and what sorts of methods, procedures, or protocols have you instituted in your work? What’s the current status and scale of the practice?

- AS

- Our practice is called Umwelt, and we are based in Santiago de Chile. We have defined ourselves as an office of practice and research, and we generate content across different scales, from the architectural to the territorial. Basically, we try to combine built and research work, freely moving between pragmatic and speculative possibilities, and always with an eye towards shaping projects as both prototypes and tools for envisioning alternative futures.

- IGP

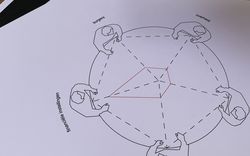

- Our process is not one hundred percent defined, but I would say that there are certain important aspects that have been always present. For us, no project starts in a neutral space, even when the project has a very defined brief. We usually begin with a research phase, exploring and critically examining the physical, cultural, and political context of the project. We look at precedents and at technical, economical, and territorial conditions. Once this context is framed, we define a series of positions to determine which aspects can be produced with architectural strategies in order to maximize the potential of the project. It’s always a continuous debate, with different, conflicting issues put on the table. Different agents and actors and objectives collide. We always ask ourselves: What is the project of the project?

- AS

- We’re a very small practice—we’re just four people right now—but we discuss almost everything together, and everyone can intervene in the different aspects of the operation. All of us design, draw, go to meetings, clean the office, etc. We try to keep that relatively horizontal. Having always been two partners, we’re used to operating dialectically, clearly communicating our intentions through the process. We talk and argue—a lot. Each of us has to demonstrate, prove, or convince.

- IGP

- Our decision to have a small practice was not really a decision: it’s a consequence of a certain economic context in Chile. There’s no solid framework that can sustain the profession as such. Many offices that have a number of workers have to compress and expand depending on the number of projects they get—which fluctuates, for example, after certain crises—and that has side effects.

Understanding Context

- FDF

- In what contexts or conditions do you operate?

- IGP

- Chile is still a highly privatized country, with few opportunities to access big or important architectural projects and competitions. The public competition system is basically a tender system, based more on economic questions than on architectural quality. So the framework for accessing new projects for an office like ours is mostly private. This generates a series of contradictions and questions we have to ask about every project: For whom are you working? Where does the money that finances the project comes from? A lot of these things are underregulated.

In terms of professional skillsets, architecture and construction work are defined in the Chilean context as “semi-formal” professions. You can find highly educated professionals, but also a lot of informality, and this leads to an asymmetrical distribution of salaries, work conditions, neighbourhood rights, etc. We have both this precarious condition and a highly developed capitalist context to work with.

But this dual condition also generates certain opportunities. For example, we were able to build projects very early—we actually started building when we were still students—and we won a few competitions, became professors, and had our own studio at the university, all when we were very young.

- KC

- Can you expand on Chile’s neoliberal culture and how you’ve reacted to it?

- AS

- Private enterprises are some of the biggest motors for everything in the country. There are state commissions, but these are very bureaucratic, and we often question where the projects that are selected are—well, if they’re actually good projects, or if they’re just cheap. In small firms, you have to start by mostly doing private commissions. Of course, this has a lot of contradictions and complications, but we’ve tried to be optimistic and to transform even these private commissions into projects with public potential. Beyond that, we’ve also initiated and promoted research projects, such as the Schapira Eskenazi book and exhibition, and our ongoing project Energy and Territory, which have given us opportunities to define our own agendas and to navigate this very fragmented environment.

- IGP

- We were at university fifteen years ago, and at this time neoliberalism in Chile was perhaps at its peak. Our education and architectural schooling directly reflected that socioeconomic condition. We were always very critical about the scopes of our projects, the goals. Both Arturo’s and my master’s theses took on an attitude of trying to understand architecture as a tool for addressing sites and contexts more than as autonomous architectural objects.

- AS

- Early on, even from our first conversations at university, we saw and we understood that this idea of the “golden generation” of architects wasn’t sustainable for us and for our generation. I mean, they’re great architects, all of them; but it’s not our reality. It’s not possible for us to work in that way. We understood that if we wanted to have any agency, we had to move in different directions, to try to get different commissions, to try different ways of working, etc. We felt that the academic and professional systems nurtured a certain professional narrowness. We were—and still are—convinced that architects can do way more than design nice buildings in beautiful settings.

- KC

- Who were some of your early role models? Were there other practices, like URO1.ORG, that helped you develop your attitude and understanding of local conditions?

- IGP

- Although we were not totally convinced by the program we were taught at university, there were a couple of professors that were shifting that scope to something more interesting. For example, we were influenced by the work of URO1.ORG. First of all, they were a collective—an anonymous collective. Individual names were not important; the name URO1.ORG was a statement in itself. What we liked about them was that they were capable of generating architectural strategies from cultural context, of using it as an engine. This was Chile in the 2000s: it was a time when Chile was hatching from its—it’s still hatching from this forcefield of restrictions put in place by Pinochet. URO were very intelligent in understanding which aspects of culture could be interpreted through architectural operations, what architecture could change culturally.

- AS

- And they were very forthright about saying that their main goal was helping with the transformation of society, with a cultural shift. Again, we were students at the time. We saw these very well-known Chilean architects’ beautiful projects at university, but then you had these young guys with a very punk attitude doing public interventions—very polemical public interventions—making prefabricated systems for housing, making interventions in public space, etc. That was very different to what we were accustomed to seeing, and I think it was very mind-opening.

- IGP

- The first model was URO for this cultural aspect of the project, and the second one was Pedro Alonso. When we were finishing architectural school, Pedro arrived from the AA, and as both an architect and a professor he had a very particular approach to understanding context in relation to larger territories. He saw context as a concept in flux that needs to be conceptualized, and in being conceptualized it can be designed. Pedro was our teacher for our master’s theses, and after we finished, we started working with him on two research, exploring these ideas of reinterpreting territory as a project itself.

- AS

- These were not heroic figures for us, like what we were accustomed to in architecture. They were a little bit older than us, and they were probably full of doubts and even contradictions, but they had very strong attitudes and critical positions.

In terms of ecology and territory, though, beyond Pedro, I don’t think we’ve had such direct references. That’s why we have always invited a lot of people into our studios and into our research in general. We invited, for example, 51N4E from Belgium; we invited LATERAL OFFICE from Canada. But we have also invited people from the private sector—the bad guys, you could say, who work at the companies responsible for the transformation of the environment—and also other social actors, engineers, etc. We try to embed ourselves in this context and to be part of that world because right now, architects are not part of that world. Even if we think we have a lot to say there.

- FDF

- Over years of projects, you’ve acted as designers, coordinators, enablers, curators, and researchers. How do these different hats reflect your approach and strategy?

- IGP

- Architects are very good enablers. For example, we are working right now on an infrastructural and cultural project called SUIZSPACIO. The Swiss Embassy called us because they wanted to place a cultural and artistic project inside a subway station. We had worked with them in the past, and they just had this idea—they didn’t really know what to do, how to materialize it, or whether there was even going to be an architectural project. We started working from scratch with several people, trying to understand the context of art in public space in Chile, of cultural space in an infrastructure system, specifically in the subway system, etc. There is a history between the relationship between art and transportation infrastructure in Chile, a certain past, and a certain present, that we needed to understand in order to think about a possible future. We helped the embassy define the goals and the process and set certain stages for the project.

- AS

- We’re in a very peripheral and also modest position as architects. In a firm like ours, we still do little projects. We think of these projects as prototypes for bigger transformations. With SUIZSPACIO, we’re exploring how to transform this utilitarian infrastructure into a public space, into a cultural space, where more things can happen than just moving around the city and buying things from the stores in these stations.

Building a Case

- KC

- Let’s continue with your ongoing research project, Energy and Territory. What is the idea behind the project? What are its goals and how do you go about achieving them?

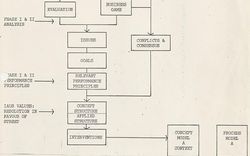

- IGP

- For the last six years, we have been working on a research project at the Universidad Católica, in a master’s studio we called Energy and Territory, that is about the transformation of the planetary energy system and its consequences and opportunities. Chile, as a consequence of its geographical and weather conditions, has the best places for renewable energy infrastructure, and so it plays a very important role on a global environmental scale. In the studio, we have been questioning whether the different kinds of renewable energy projects that will be implemented in Chile—solar, wind, geothermal, hydroelectrical, tidal, etc.—can adapt to certain geographical, ecological, and cultural specificities of place. We’re talking about everywhere from the driest and hottest place, in the desert, to the glaciers and the tidal forces of the Strait of Magellan. The idea is to understand this infrastructure as part of a territorial transformation: these energy projects will probably be the most important investments that these rural and very poor territories will receive in a long time. This is a local question, a national question and a global question, combined. And so in these six years, given the complexity of the problem, we have invited into the conversation not only architects, but also actors from both the private and public worlds, coming from the technical sphere or civil society.

All of these renewable energy infrastructure projects are, in fact, from international private enterprises. Very few are from Chile. The neoliberal condition has framed a political context in which companies from all over the world will build these projects—of course, for profit. So how can we calibrate and rethink this private energy infrastructure to be an asset for a certain and a specific context? We always debate the possibility of turning a negative externality into a positive externality. - AS

- Still, in some cases, it’s not possible: you sometimes have to be much more modest and just try to mitigate the damage that’s already been inflicted. In the south, for example, we did a version of this studio on the territorial transformation caused by the Ralco hydroelectric dam project, this massive infrastructure that destroyed ecological contexts, that destroyed a lot of the existing relationships between indigenous peoples and their environments. The company had a very technocratic vision, a very abstract and diagrammatic vision that was not related to the territory itself, nor the local communities. It was just done at a desk somewhere, just a matter of making economic and technical calculations. Our first approach was to see if we could undo this damage. It might sound a little cheesy, but the territory needed a lot of healing. So, we searched for small, acupunctural interventions that could mitigate this bad situation, but we knew much of the damage was already done; there would be no going back to what was there before the dam.

- FDF

- Can you explain some of the history of Chile’s energy management? How did we get here, and what’s been happening these past few years?

- IGP

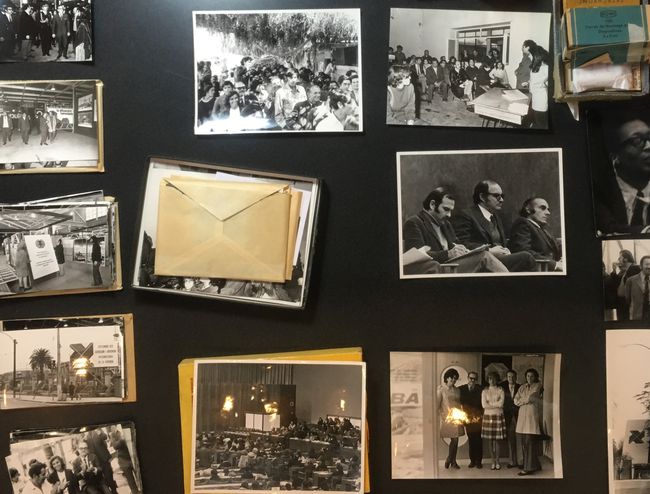

- In the 1940s, Endesa, a state company in charge of developing Chile’s electrification plan, was created. Between the 1940s and the 1970s, the electricity sector was mostly in the hands of the state. Electricity was mainly generated by thermoelectric plants—by burning coal or gas—and a series of dams, which generated hydroelectric energy. In the beginning, it was about harvesting the natural conditions of the Andes and burning fossil fuels. During the dictatorship, this company was privatized, making for the first system of free competition in energy production and distribution in the country. Today, the company is owned by an Italian conglomerate, and they have a very large capacity for generating energy in Chile.

Through the 1990s and the 2000s, the standard was to build large hydroelectrical dams. One of those dams—the biggest dam—was, as Arturo said, built in Ralco. A classic slogan was that building there was the price of progress, that it was a kind of controlled damage. But the thing was, it was a very emblematic case in history of energy infrastructure in Chile because the project flooded an ancient cemetery of the Mapuche people, and necessitated the relocation of many communities that had been living there from ancestral times. It was not only ecological damage that the dam caused. It was very controversial, and so it turned out to be an important moment in the paradigm shift for energy projects.

More recently, another key moment was in Aysén in Patagonia, where in 2010 there were plans to build a series of huge dams. There were a lot of civil actions, a lot of riots—often financed by Douglas Tompkins’s foundation—that made for a certain common awakening among the population of Chile to the true price of progress. People understood, especially after seeing how dams had caused so much damage in places like Ralco, that the ecology of the territory was more important than building a dam. The project at Aysén was canceled both because of this public opinion and because of certain economic changes that made building large hydroelectric dams unsustainable.

At that point, the government, understanding that Chile had this big potential for renewable-energy projects, gathered a board of different professionals that designed something called Energía 2050, a framework for turning Chile into a magnet for further renewable-energy investment. The idea was to switch from burning coal and petroleum to using renewable energy in a certain number of years. It’s actually kind of working—and faster than expected.

So, now many projects are going to be built here. They sound clean in that they do not depend on fossil fuels, but their design, implementation, and impact is not regulated nor taken advantage of in the way it should be. The idea of the studio and of this research is, in general, to reenvision and rethink this infrastructure; if we don’t, it will be a missed opportunity.

- AS

- Yes, so the question is: how can this energy shift be not just a transformation of energy sources, but a tool for the transformation of societal issues and the way we approach infrastructure projects? How can these new projects become public assets and actually have a relationship with their contexts? When we were starting our studio, we approached Endesa, talked with them and told them what we were trying to do, the way we were trying to work, what we were interested in, and what we thought architecture and design could bring to the table. They were actually very interested.

In the beginning, we started by talking about sustainability, but then the conversation started to expand: they invited us to see some of the new projects that they were doing, we went on site, we met some of the communities. The process started to gain momentum, and at some point we were super-optimistic—we thought we were going to be able to get inside the company, maybe even hack it a little, and to start doing these projects inside of this big mammoth, like a little virus. We started to have more meetings with more people; they were very interested in bringing us on, and so we wanted to formalize the relationship with a contract, but it was at that point that Endesa was finally bought by the Italian conglomerate. All of the people we were working with went out. It was like the company was beheaded, and all of these actors were changed out. And the Italian side had a totally different attitude about territories and communities.

Since then, we have been thinking about how to engage with the lower part of the chain and not only with the top actors. How can we work with local organizations to push this transformation from the bottom up and not only work directly with big companies?

The development of territory is understood today as a competition for land and resources between producers on one side and local communities and ecosystems on the other, with the latter usually losing out. We try to imagine new ways of mediation and coexistence that are more complex and just.

- KC

- How do you balance these convictions with the modesty necessary to practice architecture?

- AS

- After all these years working in contexts like these, we have retrofitted our own way of looking at more traditional projects. We’ve always liked a phrase from the French politician and ecologist Nicolas Hulot about how we have to be able to get to the end of the month, but also confront the prospect of the end of the world. We try to move between these very speculative, visionary possibilities and these very direct and pragmatic problems that have to be solved right now.

And working with all these energy and territorial issues, especially lately, we’ve had a lot of discussions about ideas of post-carbon, postcolonial, and post-patriarchal ways of living, asking ourselves, How can you bring this from the studio to very traditional projects? How can we understand these projects as part of this post-carbon transformation, probably the biggest transformation we should make? Of course, we don’t have any answers yet.

This conversation is the second of a series of interviews conducted by Plan Común that unfold both on this website and in video in the audiovisual archive OnArchitecture.