Not mere travellers

Niklas Fanelsa on approaching patterns

This essay is the first of three that will unfold as part of Patterns of Rural Commoning, the project of Niklas Fanelsa, 2019-2020 Emerging Curator.

The countryside is once again a focus of attention as a place that generates patterns of life, work, and production that are desirable to city dwellers. In rural areas, places emerge that bring together expertise, skills, and inhabitants to create instances of commoning that present a heightened awareness of locally built space and local social networks. In the countryside, groups gather to elaborate and extend the local context with a holistic approach toward living and working. The scale of the village allows it to become a testing ground for simple implementations of common activities. In such a non-anonymous surrounding, the impact directly affects the daily life of the whole community, promoting place-based development.

I first experienced the atmospheric qualities and lifestyle of a countryside while studying architecture in Japan. My colleagues and I spent many weeks in Niigata, a rural area in West Japan, where the culture and architecture are strongly connected to the seasons—Niigata receives more than three metres of snow in the winter. With fellow students, I executed the construction a mobile food cart that was used for a cooking performance on the occasion of an exhibition opening. Together with local craftsmen, we repurposed wood from a former farmhouse, made joints, and assembled the construction. Equally rewarding to this practical work was the everyday experience: we lived together with the locals, sat around the kotatsu (a table heated from below) until late in the night, attended their festivals, and tasted their regional cuisines. As students from foreign countries or the metropolis of Tokyo, we were unfamiliar with this rural condition wherein, beyond one’s main profession, one could be so skilled as to build and repair their own house, grow and pickle their own food, and participate in their local community. Our tasks as students had given us a framework through which to engage with the village, to collaborate with local craftsmen, and to organize events with the inhabitants, that altogether formed an immersive learning and holistic understanding of the context and local, common practices. This approach contrasted the strategies that we were familiar with within the city, where we were taught to focus on the planning and design of a task, rather than its direct and physical implementation in a context of inhabitants, seasons, and construction materials.

When I returned to Germany, I finished my studies. I joined a group of five fresh graduates, and we decided to collectively work on a small physical structure instead of starting regular positions in offices. We had learned architecture through conceptual design exercises and lessons on the correct way to construct according to legislation and industry standards—and we felt that this education had actually removed us from the production of meaningful contributions as architects. We wanted to get our hands dirty in a literal sense and we wanted to break with the expectation for a graduate to enter a world of famous offices with an ambition of winning competitions. An alternative setting would allow us to work and live together, test our skills, and learn more about construction without the economic constraints of an architecture office.

We decided that the best place to do this was Walsdorf, a 450-inhabitant village in the West German countryside, the ancestral home of one group member. With the village came our first client and their request for a garage as a workshop. For our salary, we negotiated free board and stay in an existing house, and we were to be supplied with materials and tools for the project’s construction. With no expectations and no practical experience, we were there for what, in the end, was almost eight months. During this time, we did everything by ourselves, from pouring concrete and building a timber-frame structure to making windows, all while sharing the same apartment.

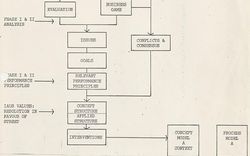

For us, it was an opportunity to test an alternative approach to design and construction in a collective way. Normally, the production of a building is separated clearly into different phases. First comes a preliminary draft, then a detailed design, then its execution, and so forth. We omitted this procedural principal and, after we decided upon a site for our project, began working on a foundation without knowing what the final design would be. Normally, the people involved in a building project have clear professions and hierarchies. For us, a collective breakfast became a day’s first team meeting and, afterwards, we would research and draw façade details, then cook a collective lunch, and then work on site in the afternoon.

I then spent some years in the profession in Belgium and Germany before starting my own practice in Berlin. I had almost forgotten about my previous experiences until I heard from a friend that a group of Japanese ex-pats had opened a café in the German countryside in a town called Gerswalde, 100km north of Berlin. I went to see for myself and found an authentic Japanese curry served in the intriguing atmosphere of an old house transformed into a café with a gallery. The owners had complemented a rough existing structure with colourful tiles and precise built-in furniture. The welcoming hospitality of the staff, exhibitions, and surrounding nature convinced me to visit more regularly, and I did so with many people from the Japanese community in Berlin. During the time, I was sharing my Berlin studio space with a befriended communication designer. The next year, he decided to completely relocate his practice to Gerswalde, following a trend of Berlin professionals and creatives looking for opportunities beyond the expensive and dense urban fabric. After more time spent in the countryside, we realized that the café in Gerswalde is not a special case of an existing building transformed with new use, but one example of many. Amongst others, we visited Libken, an artists’ residency in a former prefabricated building, Hof Prädikow, a large-scale co-housing project, Stolpe, a concrete factory now functioning as an innovation center, and Basta, a community-supported agricultural farm. Through collages, mappings, and interviews, we tried to establish a platform and discussion among the places. Through observing these case studies of similar scale, we discovered a shared narrative.

In our findings, we saw a challenge to the given paradigm of the rural as the space of tradition and shortage. For us, much of the innovation emerging from cities is aimed at or absorbed into a global capitalist system. Through our rural case studies, we saw spatial and economic opportunities that encourage a variety of self-sufficient lifestyles. We encountered inhabitants that draw resources, expertise, and practical skills drawn from their immediate context to include in their daily lifestyles. This occurs at very small and expanded scales to affect larger groups. For example, a community-supported agricultural farm may produce food for a local network of consumers. The consumers may then become interested in how their food is produced, and the farm welcomes them, teaching new skills that allow the consumers to participate in the farm’s daily operation. Here we saw that the rural condition can support networks that are independent while encouraging stronger local identity.

In autumn 2019, I returned to rural Japan with Jan Lindenberg, founder of the project space löwen.haus. We wanted to see if the rural developments that we had identified and mapped in rural Germany could be found in other countries around the world. Starting from Osaka, we went for a two-week trip around the Seto Inland Sea and Shikoku Island, meeting activists, architects, and initiatives that are active in the countryside. In particular, we were looking for strategies of commoning manifested in realized projects, approaches to current questions in society, and new behavioural structures within the communities that we visited. In the Japanese context, the Fukushima nuclear crisis of 2011 had prompted many to rethink their urban lifestyles and to restart in the countryside. These newcomers sought a self-sufficient lifestyle within a small community, houses built with a reduced carbon footprint that consume less energy, ways of working in close proximity, and models of living together beyond the nuclear family. Nevertheless, it was important for many to remain connected to the city. We found new rural architecture types—satellite offices, food co-ops, and remote community spaces. On Shōdo Island, a small community center is connected to another in the city, and the two exchange resources, staff, and exhibitions. A design company locates part of its office, together with its server building, in the small village of Kamiyama, allowing employees both urban and rural work settings. A food co-op in Kobe directly connects farmers with their end customers so that young farmers may start businesses outside of established networks. With us, we brought a two-sided map that explained our home context of Brandenburg and displayed the subject of our journey, the spatial connections of places and people in Japan. With this map, we were not mere travellers, but researchers investigating specific types of common activity that occur internationally.

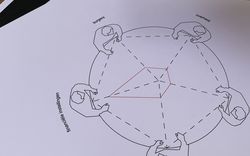

For me, questions remain of how personal experiences, practices, and understanding of this rural movement could be visualized and communicated. How can something that happens in different parts of the world be connected and portrayed with equal focus across all instances? Thus, I became interested in the term “pattern,” which is not connected to scale or place but relies more on similar environments and relationships, which is a helpful concept. With this approach of observing a specific local finding, then carefully analyzing and describing it, and then examining it in a variety of different contexts, a more universal pattern emerges that may allow us to, with a global scope, understand and learn from the similarities and differences between a wider range of rural practices.

Related articles