The Architecture of Cooperation

Kim Courrèges and Felipe de Ferrari of Plan Común speak with Carles Baiges and Cristina Gamboa of Lacol about cooperativism, participatory design, and political engagement

The Practice as Project

- FdF

- Can you tell us about the specificities of your practice—its form and framework, your attitude and strategic approach?

- CG

- Lacol is a cooperative of fourteen architects based in Barcelona in the neighbourhood of Sants, which is a neighbourhood with a strong history of cooperativism. This history influenced us when we decided on what kind of studio we would be. Basically, we started working together as students, sharing resources, sharing methodologies and ideas, and when we graduated, we simply continued working together.

- CB

- At university, we realized that we shared a point of view and a critical attitude. We were critical of the types of projects assigned to us, of the faculty’s approach to architecture, and of what we understood through our early experiences as interns in architecture offices as the mainstream model for practice.

- CG

- It’s also important to note that we graduated in 2010 and 2011, when the effects of the 2008 economic crisis were still very severe in Spain. Working collectively seemed like the only way for us to start a practice with any kind of stability and dignity.

- KC

- So your organizational model arose as a reaction to an economic context. What are the methods, procedures, or protocols that came out of this?

- CB

- As architects, we wanted to avoid understanding our role as being above everything and everyone, or as deciding which questions have to be answered. We think that the role of the architect is to be embedded in society, to understand the context in which architecture operates, and to collaborate with other professions, with people living in the area. We don’t like to design by ourselves in our office, coming up with some great idea that’s going to solve the world’s problems. That’s not how it works. We work with people who have knowledge we don’t have, including those who are going to live in the places we design.

- CG

- In that sense, it’s difficult for us to differentiate between being architects and being parts of our neighbourhood, parts of society. For example, as a woman, I feel we have to change many things in the architecture community, which is very male-dominated. We are always involved in discussions that impact us, our bodies, our places in the world. And I think it’s essential for us to understand our work from an intersectional perspective. Everything we do is interrelated; our actions affect people, and that includes ourselves.

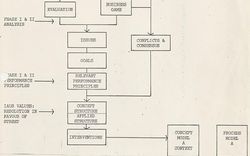

Looking back at our almost ten years of practice, we see three main aspects that we think are essential to our understanding of architecture: cooperativism, ecology—which affects our discipline as a whole—and participation. We see our task as providing tools for self-managed projects, a sort of support role for communities’ emancipatory processes of transforming the urban environment.

- KC

- What are the concepts that you find recur in your daily work?

- CG

- Our vision at Lacol is to promote infrastructures for the sustainability of free life, which we think is essentially connected with the practice of cooperativism. I would say that the idea of ecological and social transition, also from a feminist perspective, is very present in our work, but I don’t know—

- CB

- [laughs] Yeah, we are very bad at labelling or classifying our work. I think we are better on talking about the specific tools that will sustain life in an eco-social way. Part of what we do is about reducing demand on resources, reducing how much money we spend. It’s nice to aspire to a good life, but it’s possible that version of life is not the most sustainable, egalitarian, or communitarian, no?

- CG

- In that sense, we realize here at our housing cooperative La Borda, which we designed and where we live, how daily routines or daily habits can be transformative, and how architecture can be instrumental in implementing new habits. At La Borda, we can collect data and assess the impact. We can evaluate how much energy we save by reducing the temperature of the laundry room. La Borda is a kind of sandbox or laboratory for us, and what we learn there can be scaled up to produce new protocols of urban transformation.

- FdF

- What is your practice’s economic model like?

- CB

- We tend to work with very limited budgets and with people who have little access to funding. Economy is, in this way, one of the key elements of our work. We have to find cheaper ways of doing things, but also, we learn to engage alternative financial models, and this also makes us change certain things. Instead of working on projects that take many years, we try to make quick interventions that can then evolve. For instance, the communal kitchen at La Borda took longer to finish than the rest of the building. Once residents moved in, we could discuss and change certain things in the design of the kitchen, things that we weren’t able to predict before the building was in use. This not only reduced the project’s financial burden at the beginning, but improved the final result.

- CG

- In terms of the financial model of Lacol, we maintain a sort of balance between working with private sector, with the public sector, and especially with social-economy organizations, which typically come with budget difficulties. The decisions about where or with whom we work are sometimes related to these difficulties.

Understanding Context

- FdF

- How would you describe the context and the conditions in which you operate?

- CB

- I think we can agree that we live in a rather extreme capitalist context. Housing, for instance, is treated as a commodity and not as a right, and this has an impact on our lives and on the products that we create as architects. Housing is where you see this capitalist context most clearly, but the dynamic also permeates public space, workplaces, etc.

- CG

- The fact that we work in a cooperative ecosystem, with many actors and opportunities, is our kind of counterbalance to this.

- FdF

- There is a strong tradition of cooperativism in Catalonia, and there’s been a significant rise in the strength of collectives there in recent years, particularly in Barcelona. How do these local conditions affect your work? It seems there’s hope—and also concrete possibilities to develop emancipatory projects.

- CB

- We do have a strong sense of cooperativism and a cultural tradition of community activism and resistance. And we also have certain people in government and in different parties that are receptive to this tradition, especially at the local level. There are always certain people in the administration willing to fight for alternative ways of working, sometimes unexpectedly. In the case of La Borda, for instance, the land was granted by a conservative city government. We’ve been lucky to find people that are willing to work with us and to find solutions to our questions.

- CG

- We work in an environment with a heritage and with a history, and I think part of our work is to recognize this history. At Lacol, we share a space with other cooperatives, and the members of one of them have been researching cooperativism for many years and proposing new cooperative models. Our work as architects is enriched by the work sociologists, journalists, and researchers are doing to shed light on these kind of histories of our neighbourhood.

We have also been working with La Dinamo, a foundation that promotes cooperative housing, and with Coòpolis, a kind of social-economy incubator. This work involves generating new forms of economy or implementing new housing policies, and I think this is blurring the limits of our activity.

- KC

- Do you consider your methodology a model in itself? Is it scalable?

- CG

- We’re used to working with local communities, to being present among them and being involved. It’s difficult to imagine how we can scale it up, how we can work in different areas. This proximity, our knowledge of the place, is essential. In our projects, we really know the people, the agents, the associations; to think about how we can expand and how we can bring this knowledge to another place, we would need to know who’s there, who can transfer the knowledge of that place and how we can interact with them.

We’re also used to talking with people that we know in the place and asking them about the commission, asking if it’s needed or not, if it will receive support. We try to be a partner. Part of our methodology is to avoid being parachuted in.

- KC

- What about your political engagement? Did you, for example, participate in the anti-austerity Indignados movement?

- CB

- We didn’t directly take part in the Indignados movement. Instead, we were involved in neighbourhood struggles, claiming different areas for our community. One of them was Can Batlló, which at the time was still an underused private factory. We engaged with our neighbours to make the factory part of the neighbourhood and meet the needs of the community. The same happened with other projects in the neighbourhood, like La Lleialtat Santsenca, which also became a community centre. Today, our position as activists is mainly related to housing and the social economy. We put our energy and our thinking into helping communities to create housing cooperatives, or into lobbying the government to find grants and land for new projects. At the same time, we are part of a network of cooperatives that help people to materialize their social-economy projects by advising them on how they can find support, space, guidance, or grants. That’s where we put our energy.

- FdF

- How have other people’s experiences in, for instance, the Mietshäuser Syndikat in Germany or the Federación Uruguaya de Cooperativas de Vivienda por Ayuda Mutua (Uruguayan Federation of Mutual-Aid Housing Cooperatives, or FUCVAM), helped you develop your understanding of cooperativism?

- CG

- FUCVAM is essential, and also the Andelsbolig model in Denmark. It’s important for us to understand the protocols from other geographies’ models—how they relate to their municipalities, to the public sector, and to their technicians, architects, and users—to see how we could implement changes in our own political and economic context.

- CB

- Both the Institutos de Asistencia Técnica (Technical Assistance Institutes) in Uruguay and the Serviço Ambulatório de Apoio Local (Local Ambulatory Support Service, or SAAL), which came out of the revolution in Portugal, have detailed models of relationships between professionals and other groups. These are formal organizations of professionals that support the needs of the community and work with them. During the Second Republic, at the beginning of the Civil War, there was a union of architects that distributed their work, looking at the needs of the population.

- CG

- In all this—in all these precedents, we realized that it’s not always about what’s public or private, and that civic power has a kind of agency. These cooperative-public kind of collaborations have potential in that they show us how to produce new protocols, and I think that this is what we are looking at in these models. The way we work is also a kind of a political tool.

Building a Case

- FdF

- Let’s continue with your process, taking La Borda as a case study. What were the most effective tools of engagement you developed? Can you tell us more about the participatory funding system?

- CG

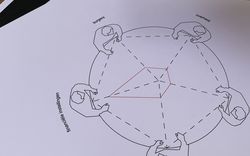

- La Borda was our collective solution to a lack of housing. It was based on collective ownership, on a search for new forms of conviviality, on ideas of cooperation in the domestic sphere, and on a relationship with the scale of the neighbourhood and existing networks and social economy. These values then led our discussions with the users. We had an assembly of fifty people, more or less, and a series of working groups, of committees, and one of these was on the project’s architecture. In all of these discussions, we shared the design process with the architecture committee, explaining the steps and challenges along the way and the questions the design brings out, and then the committee prepared a workshop sharing this with the rest of the assembly.

In terms of development, we wanted to disrupt the pattern of housing speculation, so it was essential for us to look for new alliances outside of the conventional banking system. La Borda was the first housing project financed by Coop57, a cooperative of financial services, which provided a loan. Importantly, this loan was also developed in a kind of participatory way. It was people, institutions, and foundations that supported the project—a result of a kind of a crowdfunding. And so the project was a pioneer model, a prototype with which we as architects and as parts of the development team could systematize this process and highlight what’s crucial in order to make this kind of development easier for future groups. This is part of this generosity of the project, sharing this process.

- FdF

- What have been the main lessons of La Borda, both during its development process and during its occupancy? How does it feel to experiment using your own body?

- CG

- Through two years living in La Borda, there’s been much to learn. Of course, we’ve been in the middle of a pandemic, so this new normality alters everything in a way. To see how the building has behaved during the pandemic, and to see intermediate spaces used as gyms, as concert halls, as dining places, as schools—we’ve had the opportunity to look at certain protocols of care, of use, of cleaning, of mutual help. Even when isolated, you can establish certain kinds of relationships. Suddenly the guest room was a working space because people couldn’t receive any family, friends, etc. The adaptability of the project’s spaces turned out to be essential for this moment.

Another thing we learned is about the role of kids in the process, and about participation and inclusivity from their lens. There were not many kids when we started; many were born during the process. But we design for everybody, for all different kinds of skills, bodies, needs, etc. We often discuss what could have been done differently. - CB

- There’s something to learn in all layers. We also now monitor different apartments to see how we can change certain things, either here or in new projects. We see what can be improved or transformed. Like this big multipurpose room: it’s very good for certain things, but less convenient for others. It’s a space that kids probably enjoy the most, but it was not designed specifically for kids.

- KC

- Can you briefly introduce your workspace, La Comunal, and its role in the cultural field?

- CB

- For the last year or so, we’ve been working in a new space, in an old factory that we refurbished with seven other cooperatives. We still have our own offices, our shop—there are different spaces that each cooperative separately manages and uses—but we share meeting rooms and gathering spaces. The move was also an opportunity for us to find synergies with other cooperatives. Most were already very present in the neighbourhood and some of them we had already worked with or exchanged ideas with, but we were separate physically, and therefore, we could say, mentally. The goal is that the place where we work becomes a kind of headquarters for cooperative and social-economy organizations in the area.

- CG

- What we learned from historical cooperatives is that they were basically spaces for collectivization, for solidarity. La Borda and La Comunal are also infrastructures for resilience and for survival. It’s important for us to establish means of protection and safety from the challenging future we will all have to face.

This conversation is the first of a series of interviews conducted by Plan Común that unfold both on this website and in video in the audiovisual archive OnArchitecture.