Circular and Solidarity-based Construction

Kim Courrèges and Felipe de Ferrari of Plan Común speak with Clara Simay of Grand Huit about circular economy and redefining a project’s stakeholders

The Practice as Project

- KC

- Can you present the philosophy behind Grand Huit—its structure and operation?

- GH

- Grand Huit is a cooperative founded by the architect Julia Turpin and me. We’re deeply invested in the region, and each of the projects we take on is an opportunity to promote sustainable models by giving value to local resources and stakeholders. The cooperative grew out of a need to bring coherence to our professional practice and our civic engagement in local organizations that deal with inequality or resource preservation. Our volunteer commitments were taking up more and more of our time, and since architecture condenses all of these social issues, we decided to bring our volunteer work experience into our projects to give them an entirely new dimension. This allowed us to reposition our work at the intersection of social and environmental issues. In our practice, this integration begins more specifically in the direct environment of our working and living spaces. We’re located on the Bassin de la Villette, which connects to the Canal de l’Ourcq, in the eastern part of Paris where we live with our families. .

Our team chose the cooperative as a model of shared governance. The SCOP - société coopérative de production (cooperative and participative architectural agency) has a rather specific status as a cooperative and a history among the working class. It functions on the principle of “one person, one voice” and during a vote, the organization’s policy choices and decisions are made horizontally. Whether you’re a founding member or not, everyone is equal.

Cooperative status is in fact unfettered by productivism insofar as there is no speculation and all earnings are reinvested in the work or its tools. We’re founding partners but also employees of the cooperative.

It’s a model that seemed perfect for the way we wanted to operate and it’s become part of a community of social and solidarity economy organizations. This notion of implicitly recognizing the value of a network of associative and cooperative structures creates local exchanges and synergy within our practice every day.

- KC

- What is your work process and your position in relation to a project’s stakeholders?

- GH

- As I mentioned, we pay a lot of attention to neighborhoods (inhabitants, associations, businesses), because they’re the real reason these projects can move forward. This means doing the daily work of building relationships, spending time in different areas talking to people, and observing and following those who do things differently.

It’s really important to us to be part of a site’s development over a long period of time—well before we begin working on it and well into its future. We’re involved in multi-stakeholder projects, often within a framework that is much broader that the realm of construction. Our network of partners extends to every kind of individual and organization that is part of the local social and solidarity economy: tradespeople, social associations, cultural centres, restaurateurs, gardeners, and so on. As the needs of our projects and their uses evolve, so does our reliance on each other. As for more institutional stakeholders, like elected officials or public structures, we work more openly and horizontally to establish mutual trust, potential exchange, and to benefit from each person’s expertise.

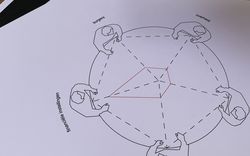

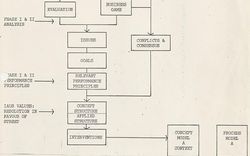

Such a multitude and heterogeneity of stakeholders calls for a particular type of management. We systematically try to propose a shared governance system, both while managing the “project, evaluation, construction” phases and during the site’s future operations so that during the project’s development, new stakeholders and new residents who weren’t necessarily part of it at the very beginning can naturally find their place within the system—and the system can maintain continuity beyond our involvement. We try to ensure that the project is an exact reflection of the people who brought it to fruition, but that it can also live beyond them as well.

We also feel that the site becomes alive the moment we begin imagining its potential use. We really want to get rid of the whole concept of a delivery date for a disconnected urban object—which would typically signal the end of our work—when we hand over the keys. We have a hard time letting go of our projects. We keep in touch on a monthly basis even if there aren’t any specific architectural issues to discuss, since the projects we work on are often in the neighbourhood where we live and work.

- GH

- As for our position within the group of stakeholders, we want to work together with the clients, to focus on the needs of the people we work for and on the larger environment, the neighbourhood, the city. We bring together stakeholders who aren’t directly involved in architectural design in the traditional sense; to completely open up the project’s partners by working with neighbourhood residents and business owners, and also local authorities. In this climate of rising right-wing extremism in Europe, it’s very important for us to hold onto this traditional political aspect because it also needs to be part of the equation. It gives legitimacy to elected officials and connects them to their jurisdictions.

By re-examining our position as practitioners in relation to our clients, we noticed that when we open that up, everyone is interested.

Preserving resources at the local level while creating spaces for people who are in very vulnerable states seems like an obvious thing to do in a city. Making use out of abandoned materials the city no longer needs while providing for those who have very little space in the city also means making things better for everyone, and most of all, we’ve noticed, it’s a sustainable approach that everyone can understand.

- FDF

- Tell us more about your day-to-day operations. Can you talk about how you manage your projects?

- GH

- Every week, each of our projects’ phases and issues are reviewed by members of our cooperative. A team comprised of a manager and an assistant is in charge of each project.

Every project is a chance to try something new, to research innovative construction methods, get funding to conduct lab tests on bio-based materials or materials that come from local construction waste streams.

If I look at our path over the past few years, each of our projects was another step in our evolution, allowing us to push things a bit further and more radically, environmentally speaking. We never adapt one single working method—to be honest, anything is possible. For example, on our next project, the renovation of a train depot in the 19th arrondissement, we decided to relocate our office on site, including during the design and consultation period with the future occupants. This way, we can fully understand the potential of what’s already there and introduce only what’s necessary for the needs of its future residents.

To not build has become our primary act as architects. To conserve what is already there, to develop it with local stakeholders. We’ve now decided to turn down any new building projects and concentrate solely on renovating existing structures.

We can no longer imagine designing buildings without forming a continuous dialogue from the very start with those who are going to be part of its transformation. It seems necessary in terms of eco-construction techniques, but it’s especially the case when it comes to the reuse and transformation of materials. In our daily work environment, communication with tradespeople is very horizontal. Very quickly, we begin working with them on design details and the choice of materials. There’s a kind of virtuous interdependence, which means that we reinvest and re-empower each other. We’re able to get past the kind of infantilizing relationship that sometimes happens with contractors.

The question of material reuse has a social and eco-construction aspect, and therefore an environmental one as well. With each site, we try to identify what our biggest material needs are and prioritize them according to their local sources, which are huge in terms of construction waste and carbon footprint. Then we have to mobilize a network of businesses that can collect, transform, and redevelop them. These tradespeople aren’t necessarily from the traditional construction industry so we need to find people with the kind of atypical skills needed to do this kind of work; for example, seamstresses who can work with textile waste or tarps that can be used to make blinds or removable partitions. This allows skilled workers from other fields to contribute to the project, but also, because we deal with businesses that facilitate social and professional integration, to open up new markets for them in the construction industry. As prescribers, we’re invested in the economic activity around this network of highly skilled local partners.

And since we’re prescribers, we have a responsibility to create market opportunities for those who work on the issue of ecological transition. The idea is also to help develop the reuse sector as well as bio-sourced and geo-sourced materials and prioritize working with these industries, to invent services that they will then be able to develop and apply to respond to other demands in the construction field. The notion of copyright never comes into play; we don’t file a patent. All of these solutions are developed as open source, with the goal of building an experienced network of local economic players right here.

In terms of skills, we’re also involved in education; helping train people for certain trades like woodworking, carpentry, or masonry, as part of the larger social economy. We also look at the reuse of stone or concrete and the transformation of materials in ways that have minimum impact so they can be used in other projects, but also generate lots of activity and labour for workers with a wide range of qualifications.

The use of bio- and geo-sourced materials, much like reusable ones, allows us to reconnect with the material itself, its requirements and properties. That isn’t feasible anymore with off-the-shelf materials. Architects are pretty unaware of locally available resources. Relearning about materials also means reconnecting with construction methods that are completely divorced from industrial carbon processes. These are often traditional and vernacular construction methods such as plastering, dry stone walls, tapestry, carpentry and joinery…

Understanding context

- FDF

- What are the conditions and contexts, both locally and city-wide, in which Grand Huit operates?

- GH

- In Paris, everything is very dense and there is tremendous land pressure that leaves very little room for transition initiatives, especially anything to do with the social and solidarity economy. Despite the existence of a sharing economy and the digital revolution that transcends the need for physical space, having a place where we can exchange, work, and live is still an essential unifying element that helps things move forward.

We live in a context of permanent gentrification. We certainly see this in the 18th and 19th arrondissements which, until recently, were fairly working-class neighbourhoods. Paris is becoming a museum city and it’s vested in the kind of business that’s tied to the carbon economy, which in our opinion must evolve. Certain populations, including—and especially—the most vulnerable, are being relegated farther and farther into the Greater Paris area. But at the same time, there’s also this constant friction with the migrant and homeless populations within the city who aren’t moving to these far-off suburbs. What little resources they can still find are in the city centre. The issue we tried to work on is precisely to give them back their place in the city by providing housing and work, namely at the Ferme du Rail.

There’s also the matter of reintegrating nature into the city. That’s one of many contemporary urban issues. Paris is somewhat blind to the very present agriculture and forest belt that surrounds it [that could allow the development of short supply chains]. In every economic field and exchange network, construction, food, energy, etc., we’re in a completely absurd system that goes through central distribution plants that are powered by global trade, and are completely disconnected from their surroundings. We must re-establish a bond of solidarity with local producers. The fact that there’s no industry in place is almost a good thing because now we need to build this relationship between Paris and its surroundings which, paradoxically, doesn’t exist. For example, it’s almost impossible to build something with wood from the Île de France, the region of Paris, even though well-managed oak and chestnut forests cover nearly a quarter of the area. What little oak wood they do harvest is sent to China.

- GH

- So that’s the larger Parisian context. As for the local context, certain things are missing that could help promote ecological architecture. Today we have aging tradespeople who have never passed on their knowledge, and eco-construction often calls for traditional skills . Paradoxically, eco-builders are far more common and organized outside of Paris and the greater Paris region. I think that a long-standing relationship with the rural environment, which is completely lost in Paris, has favoured the re-emergence of this sector.

We’re also realizing that in terms of material reuse, there’s a lack of intermediary material collection: where does the material we need come from and where does the city’s waste material go? Things get done because a lot of people within the construction industry are interested in issues around reuse. However, we’ve lost a lot of valuable time because of recycling. It’s a convenient process for the construction industry because it allows them to do a lot of greenwashing. They can keep operating in the same way by building factories with returns, profitability, investments, and shareholders. But that method goes against its own objectives because in order for a plant to turn a profit it always has to produce more waste. With reuse, there won’t be any big factories. Instead, it will be a network of workshops located near various waste deposits and construction sites throughout the area. At the very most it could be a small factory, but not much more. We will have to adapt to massive material deposits from construction waste, which is estimated at 6 million tons per year within the region. .

- FDF

- Before creating Grand Huit, did you look at any reference models, individuals, or associations that also work with circular economies?

- GH

- One of our references is Rural Studio. It really encapsulates all of the issues that motivate us every day; it’s a leader in terms of social issues, but also in terms of material reuse. It’s not just about working with the aesthetics of material recovery, there’s also a need to make things beautiful and to continue working as an architect while reinventing a creative field. Reinventing an esthetic while connecting to the needs of materials and those who will be able to transform them was the ethos behind the Arts and Crafts movement, which was also formed in opposition to a productivist model.

Building a case

- KC

- Can you talk about your Ferme du Rail project, which is emblematic of your way of working, your architectural approach, and your process of transforming the city? How did the call for submissions and your team set up go, and what were your roles as architects throughout the whole process?

- GH

- Jean-Louis Missika, then Deputy Mayor in charge of urban planning, architecture and projects for the Greater Paris region, launched a call titled “Reinventing Paris,” in 2015. The goal was to attract innovative projects.

The City of Paris opened a call for projects for about twenty lots throughout the city. Teams were given the challenge of acquiring a lot on the condition that its transformation be innovative, for example in its construction, its use, or technology. The call also talked about social innovation: what is family today? How can reversible building be applied? We had to propose something that simultaneously considered architecture, team-building, and future users. We had to rethink all of these social issues by seeking out people from the community that could carry out this kind of innovation in all its forms, because they’re the stakeholders in this project.

There was a plot in our area. Mélanie Devret, a landscape architect with whom we work on a daily basis, Yves Reynaud, the director of a social integration organization called Travail et Vie, and I are part of the same AMAP (community supported agriculture program). Together, we began thinking about this piece of land. Yves Reynaud often talked about having a space that would function as a homeless shelter but also as a place where they could take part in rewarding activities and receive training to eventually re-enter the workforce. At the same time, it was important to create a space that was open to the community and to not relegate these people to some geographically remote location, as is often the case. It would be an open and welcoming space with different programs: working, living, meeting. These main pillars were there from start to finish. We had to think of how we could physically build this space while keeping the social integration aspect at its core, even in terms of its construction because the techniques we would use to build it would have to allow even poorly skilled people to help out.

We then set up our team by finding partners who could contribute to different aspects of the project so it could begin to take shape right away and become ingrained with the people who are the most invested in its outcome. We contacted Philippe Peiger, an agroecologist, who recently passed away quite suddenly, and specialized in urban-nature issues, green roofs, and agriculture. We also approached more conventional eco-construction experts, and even restaurant owners.

- KC

- How did you finance the project?

- GH

- From the very start of the competition, we had to demonstrate our ability to raise the necessary funds. It so happened that Travail et Vie and ATOLL 75, two small organizations with whom we first discussed various use issues, are part of another group that had already founded a small property development company for another housing rehabilitation project. So they had the necessary legal status to apply for funding, and their director, Frédéric Lauprêtre, took care of that. We evaluated the cost at three million, which is both a little and a lot. The housing part was financed by public funds that are already known and earmarked in France. But the activity areas—for example the food service, which we really wanted to see happen—were a lot more difficult to finance. That portion came partly from our own contributions and loans, which had to be one third of the total amount, and partly from private grants and foundations, which was another third. But we didn’t want to depend on public funding. Then a financial arrangement covered the remaining third of 600,000 euros. It’s a future investment plan that’s actually an investment strategy to revitalize the East, the North-East of the Île-de-France, an area that has a lot of social challenges and that has received major regional investments. We benefitted from some of those funds. The whole fundraising process is quite onerous. In France, the foundation funding model is not very well established, unlike in the United States and, I think, in Canada.

- FDF

- How did you manage to work at different levels, reconciling people from different backgrounds and communities with the current French bureaucracy?

- GH

- Our collective mission was to decompartmentalize conventional usage by creating conditions for different people to meet. The community of people who live on the street is very diverse. There is no single profile. We had to work on the transition from the more private to the more shared areas; from a room to a common space on each floor, and then the restaurant, for instance. The restaurant is the neighborhood spot where you and I can go eat, but where, at lunch and dinner, the residents have their table and eat the same thing as everyone else. That was a really important foundational element of the project for us. At the bureaucratic level, however, to finance a typical housing unit, there has to be a kitchenette in each room. What this does is that, in addition to generating a lot of energy loss, it further isolates the residents in their own rooms. We negotiated with the city and showed them that better amenities would be available to the residents in the common areas. In the end, the synergy between the project’s stakeholders and the operations we set in place allowed us to get past these kinds of regulatory issues and reach our goals. It’s the multiplication of skills, each in their own area, that makes the collective stronger.

- KC

- What lessons have you learned from this experience that could be applied to other projects?

- GH

- We haven’t worked the same way since that project. There’s no question now of not being involved in the future life of a building. We also have a kind of modest position in relation to the object that is produced. We will work much more systematically on an ecosystem over the long term than on a building that needs to be delivered by X date. We’ll no longer simply be producing a beautiful object. Even if we give it material form, it’s a materiality that first of all must say something about those who helped transform it, and it must also evolve, it should be reappropriated, it should change its identity, and it’s up to us, as architects, to allow that. In terms of commitment, the “Reinventing Paris” project has allowed architects to acquire a new status. They are seen as being capable of doing more than just drawing plans, they like to get out of the office. I think the profession has been reconsidered.

This conversation is the fifth and last of a series of interviews conducted by Plan Común that unfold both on this website and in video in the audiovisual archive OnArchitecture.