Captioning Milton-Parc

Text by Francesca Russello Ammon. Photographs by Clara Gutsche and David Miller

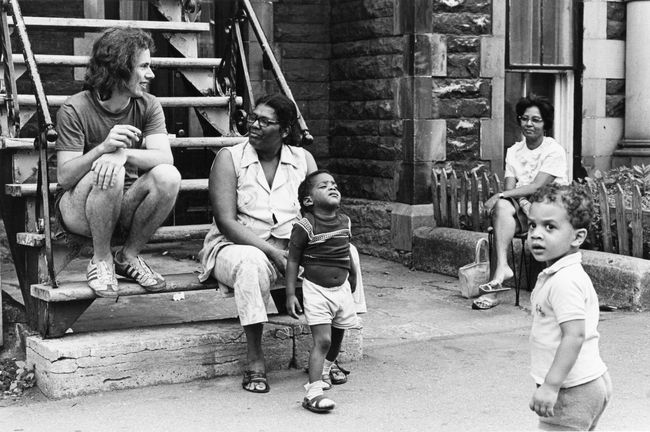

Clara Gutsche, photographer. Two women, two children and young man sitting on steps, Milton-Parc, Montreal, 1970-71. McCord Museum

“We were photographing from the perspective of living in the neighbourhood, loving the neighbourhood, loving the community of the neighbourhood. It was a sort of community that was facilitated through architecture—through buildings that were small enough so that you got to meet your neighbours, and close enough so that you went out on the street and interacted with people.” — Clara Gutsche

In the late 1960s, a private developer quietly purchased most of the properties in a six-block area of the Montreal neighbourhood known as Milton-Parc. The plan was to demolish a landscape that dated from the late nineteenth-century and redevelop it with modern construction, including twenty-five storey apartment buildings, a twenty-nine storey office building, and a hotel. A coalition of activists rose up in opposition, knocking on doors and taking to the streets. Among them were two twenty-something Milton-Parc residents named David Miller and Clara Gutsche. The pair mobilized their budding interests in photography to document the neighbourhood’s buildings and community at the beginning of a protracted era of transformation. Their work demonstrated the continued durability and vitality of an aging landscape that had been marked for removal. In this way, they continued a lineage of documentary photography focused on urban change that also includes Eugène Atget’s photographs of early twentieth-century Paris and Berenice Abbott’s 1930s documentation of changing New York.1

The visual record that Miller and Gutsche produced offers a valuable window into the relationship between photography and architecture during the era of urban renewal. Of course, they were not the first photographers to take up this subject. Images have served to picture blight, thereby sanctioning demolition, in various slum clearance projects: from turn-of-the-century Leeds, England, and New York City’s Lower East Side, to Robert Moses’s postwar Manhattan, to post-industrial Detroit.2 But the work of Miller and Gutsche expands the role of photographs in such stories. Rather than serving solely as agents of destruction, photographs can also become allies of resistance and conservation. As Miller was most interested in documenting the built landscape, his work continues in the tradition of architectural photographers like those of the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), who have composed formal portraits of significant, sometimes at-risk buildings since the 1930s.3 In complement, Clara Gutsche’s images of more social subjects recall the work of documentary photographers like Jacob Riis, Lewis Hine, and, more recently, Ira Nowinski.4 Her work also suggests that the scope of the architectural photographic archive need not be limited to buildings alone. Rather, this archive should also centrally include representations of people situated within their built environment.

Read more

-

John Szarkowski and Eugène Atget, Atget (New York: Museum of Modern Art; Calloway, 2000); Berenice Abbott and Elizabeth McCausland, Changing New York: Photographs by Berenice Abbott (New York: Dutton, 1939). ↩

-

John Tagg, “God’s Sanitary Law,” in The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 117–52; Jacob A Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1890); Themis Chronopoulos, “Robert Moses and the Visual Dimension of Physical Disorder: Efforts to Demonstrate Urban Blight in the Age of Slum Clearance,” Journal of Planning History 13, no. 3 (August 2014): 207–33; Samuel Zipp, Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010); Wes Aelbrecht, “Decline and Renaissance: Photographing Detroit in the 1940s and 1980s,” Journal of Urban History 41, no. 2 (March 2015): 307–25. ↩

-

John A. Burns, Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record, and Historic American Landscapes Survey, eds., Recording Historic Structures (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2004). See also the Historic American Buildings Survey collection at the Library of Congress. ↩

-

Riis, How the Other Half Lives; Lewis Wickes Hine, Men at Work: Photographic Studies of Modern Men and Machines (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1932); Ira Nowinski, No Vacancy: Urban Renewal and the Elderly (San Francisco: C. Bean Associates, 1979). ↩

In the early 1960s, Milton-Parc consisted of a mixture of greystone row houses, low-rise apartment buildings, commercial establishments, and institutional structures. Within a decade, the developer Concordia Estates had acquired much of the neighbourhood for renewal. In partnership with the University Settlement, a long-standing neighbourhood institution staffed by social workers and community organizers, the Milton-Parc Citizens Committee formed in opposition to Concordia Estates’s plan. Together, they argued for the continued vitality of Milton-Parc’s physical and social infrastructure, supporting the preservation of this community. They held meetings, published a newsletter, and occupied vacated buildings. Despite their efforts, demolition began in February 1972; by the end of July, the 255 structures included in Phase One of the development plan had come down, clearing the way for construction of a multi-use concrete complex known as La Cité.

While this loss delivered a crushing blow to the activists, it did not mark the end of the story. A variety of factors—including changes in the economy, local transportation routes, and eventually zoning—stalled the developer’s progress.1 Concordia Estates soon outsourced management of the existing properties, rather than proceeding with demolition and construction. This created an opening for an alternative renewal process in the remaining project area. In collaboration with architect and philanthropist Phyllis Lambert, the newly created non-profit Heritage Montreal, and federal and local governments, the Citizens Committee introduced a counterproposal. By combining co-operative and non-profit property ownership with government-subsidized building renovation, they sought to enable middle- and working-class residents to continue living in the neighbourhood. In May 1979, at Heritage Montreal’s urging, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) purchased the undemolished buildings, which included 723 residential units and 14 stores. They sold these a year and a half later to the Société d’Amélioration Milton-Parc (SAMP), a new non-profit corporation established to oversee the renovation process and then transfer the properties to their ultimate co-operative and non-profit owners. CHMC provided subsidies toward the purchases and renovations that would make affordable rent structures possible in the nearly 600 resulting dwelling units (and 20 commercial premises). They also funded the Technical Resource Group (GRT, after its name in French: Groupe de Resources Techniques), which consisted of architects, administrators, and social animators, or activists, who handled the day-to-day remaking of the project—from organizing financing to establishing architectural plans, supervising renovations, and enabling the transfer of ownership. Upon the project’s inauguration in 1983, the efforts of all of these groups helped realize the largest co-operative housing project in Canada.2

-

For a longer history of the Milton-Parc story, see Claire Helman, The Milton-Park Affair: Canada’s Largest Citizen-Developer Confrontation (Montréal: Véhicule Press, 1987). ↩

-

Lucia Kowaluk and Carolle Piché-Buton, eds., Communauté Milton-Parc: How We Did It and How It Works Now (Montréal: Communauté Milton-Parc, 2012), 11–13. ↩

The multi-year process of resistance, redevelopment, and renovation produced a substantial photographic archive. Although this archive encompasses much more than the work of Miller and Gutsche alone, their photographs are some of the most evocative, well-known, and widely exhibited from the Milton-Parc saga. During the 1970s, Miller’s and Gutsche’s photographs gave visual voice to the opposition as they were reproduced in venues including community newspapers, protest flyers, pin-ups at the University Settlement, and more formal art gallery exhibits (including the accompanying catalogue, “You Don’t Know What You’ve Got ‘Til It’s Gone”: The Destruction of Milton-Park).1 Today, the photographs help document both landscapes that have been lost, as well as the process of resistance and cooperation that met renewal in Milton-Parc. Some of that spirit continues into the present. These images can currently be consulted in multiple institutions, including the Canadian Centre for Architecture—the main repository for Milton-Parc records, in general—the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and the McCord Museum.2 Concise, utilitarian captions accompany most of these photographs. These brief descriptors typically indicate the place and date of the photographed scene, and possibly also identify the basic subject. But they tell us little about the function and meanings of these images, from the moment of their creation through changing contexts across time.

Thick captions and historical narratives

Using the concept of what I am calling “thick captions,” I aim to enrich the historical narratives surrounding these images. These “thick captions” can derive from a variety of sources, including the larger body of images within which individual photographs are situated; various textual documents related to the Milton-Parc project; and, most critically in this example, a new oral history archive I have developed by interviewing individuals involved with the project from the 1960s forward.1 Despite the voluminous Milton-Parc archive held at the CCA—including reports, pamphlets, newsletters, and newspaper clippings—little of this material directly relates to the photographs.2 Oral history interviews introduce another kind of text against which one can read these images: the words of the photographers, residents, activists, and organizers themselves.

The images that follow pair individual photographs, often in their published context, with interview excerpts from Miller and Gutsche.3 This juxtaposition suggests a research methodology for using architectural photographs as sources and demonstrates the value of oral history as a tool in that process. These “thick captions” help reconstruct some of the integral visual narrative behind Milton-Parc’s renewal. They also reveal multiple—and, at times, unexpected—roles for photographs in shaping urban development and communities. Finally, they stretch the bounds of the category of architectural photographs. Images of buildings are an obvious part of this archive, but other photographic subjects are also necessary to tell these buildings’ stories.

-

The Milton-Parc Oral History Collection is currently being transcribed and edited. It will soon be available to researchers at the CCA. ↩

-

See the extensive Fonds Milton-Parc AP025 and Milton Park Vertical File, both held at the CCA. ↩

-

All quotations in the slideshow and article are taken from: David Miller, interview by Francesca Russello Ammon, Transcript, 2 August 2016, Milton-Parc Oral History Collection, CCA; Clara Gutsche, interview by Francesca Russello Ammon, Transcript, 21 March 2017, Milton-Parc Oral History Collection, CCA. ↩

“A lot of our impetus was discovery, on a personal level. Neither of us was trained as a photographer. It was also political, because we would have generally considered ourselves political left and socially oriented, and the fact that the Citizens Committee was resisting their neighbourhood being taken over and torn down kind of appealed to us. Number one, we didn’t have any particular desire to move out of the neighbourhood, because it was going to be torn down, but also it seemed like a sort of socially useful thing that we could do.” — David Miller

“If you’re trying to make something look dilapidated, it’s quite easy to do that. You pick your point of view. In addition, if you’re a little more sophisticated, you can photograph in greyer light, you can do close-ups so that it excludes the flower bed in the neighbouring house. If you’re trying to make that same place look good, you pick very attractive light that brings out surface texture where you want to. You use, as I did then, a view camera so the lines are straight. Nothing looks like it’s falling down.” — David Miller

“But when you look at the work that we produced, generally speaking—unless we were photographing the demolition—the buildings we photographed look good and salvageable and even attractive. One of the advantages of shooting them with 4 x 5 is, when you enlarge them, you can see the padlocks on the doors.”

— David Miller

“We were literally, self-consciously, consciously—were propagandists. When people look at the images, they say, ‘Oh, that’s beautiful.’ Well, [we were trying to show them,] you live right next to it. That was the intent, and I know that that did play out to a certain extent…Who knows how effective or ineffective those photographs were in the context of Milton-Parc, but it’s hard to see that kind of thing as being detrimental to the cause. Possibly useful.” — David Miller

“The threat of demolition from Concordia Estates was quite real, and we felt that our photographs could contribute to the struggle to save the buildings.… Something about the Milton-Parc Citizens Committee and the kind of residents who were there fostered this encouragement of people with different expertise contributing in the way that they were best suited to contribute.” — Clara Gutsche

“The idea was that we would try through our photographs to show people the value of what they had before they lost it, with the hope of getting more people involved in fighting to save the neighbourhood.” — Clara Gutsche

“I found the words for how we saw our photographs contributing to the Milton-Parc Citizens Committee set of initiatives. One is consciousness-raising—a term that came out of the feminist movement—in other words, the idea of raising the consciousness of the neighbours, the community. The members of the Milton-Parc Citizens Committee were, of course, already very aware of what was happening, but the photographs still provided reinforcement, or maybe some added motivation or momentum.” — Clara Gutsche

“I do think—especially for this project—most of my photographs are based in the structure of space, the light that enters through windows. I usually photographed with window light, and very often with some supplementary added fill light because I needed that fill light. I had to balance out the contrast of the light. But I think the interior photographs are based in the structure of space and light, and that’s an architectural concept.” — Clara Gutsche

“Almost always I would go and talk to the people before going with my camera, and sometimes I went with a camera if I’d already established a phone contact or met them at one of those University Settlement group meetings or some other situation… I made the promise to return a photograph to them. So there was also that level of distribution of images into the community.” — Clara Gutsche

“During one of these demonstrations, Clara and I were both amongst the 59 demonstrators who were arrested and chucked in jail overnight.” — David Miller

“I did do a set of photographs in a couple of different buildings that had been boarded up, that the Milton-Parc Citizens Committee was actively trying to save… Unfortunately the demolition people were taking the interiors apart. I have a few pictures of the interiors being dismantled. You can see in the picture that things have been taken off the wall. The fireplaces are on the ground or sinks are on the ground. And I took a couple of photographs with the workman. This workman is about to throw a sink out the window.” – Clara Gutsche

“They started demolishing. I took a lot of demolition pictures… But it was depressing. It meant we’d lost a major battle. And at that point, I think we decided to move out of the neighbourhood. We couldn’t stand looking at blocks of devastated buildings that we had fought to preserve.” – David Miller.

Although Miller and Gutsche finished their Milton-Parc photographic project in 1973, the images have continued to circulate, both within and outside the neighbourhood. During that circulation, they need not be divorced from the context they more easily maintained when exhibited closer to their original time and place. Gutsche reflected, with some frustration, on recent interpretations of their Milton-Parc work today:

I found myself objecting to the contemporary perception of our photographs, because when they’re exhibited on their own, you see the destruction of Phase One and not the preservation of Phase Two. It looks as final as it was for Phase One, and there isn’t—through just exhibiting our photographs—a way to begin to represent or a way to initiate a conversation about the short timeline that those photographs represented and that the Phase Two was a triumphant success.1

That success built, in part, upon the social life, community spirit, and architectural character the photographers so vividly documented during Phase One of the Concordia Estates redevelopment plan. Milton-Parc activists were trying to save both the buildings and the community, and Gutsche and Miller’s photographs illustrate that clearly. Gutsche also expressed concerns that the images are sometimes understood today purely as documentation—as if she and Miller had primarily viewed the photographs as a means to preserve the memory of the community, in case the buildings themselves would be lost. But that was not the case. “It really had nothing to do with documentation,” she asserted. “We most genuinely would have preferred to have saved the buildings and not had the photographs. If such a choice could be made.”1

Understanding these nuanced purposes, meanings, and impacts requires a deeper reading. Looking beyond the photographic frames and the limited timeline of the images’ production helps take the images out of a more strictly artistic discourse and into a more social and political one. The “thick captions” afforded by archival pairings—especially with oral history texts—offer one method for revealing that fuller context.

Francesca Russello Ammon developed this research while at the CCA in 2016-2017, as part of the Multidisciplinary Research Program Architecture and/for Photography, with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.