Architecture Made for TV

By Samuel Dodd

By the 1970s, television culture permeated every facet of information exchange in America. According to a Roper survey in 1974, the average metropolitan viewer spent more than three hours a day watching television, and of those polled, 65 percent received most of their “news about what’s going on in the world today” from TV.1 Between 1976 and 1984, the Connecticut-based architecture firm Moore Grover Harper (MGH, now Centerbrook Architects) capitalized on television’s reach by producing a series of live planning charrettes called Design-A-Thons. These programs merged techniques from telethons, game shows, news broadcasts, and talk shows, and represent one of the few instances in which American architects used live television as a forum for presenting the public with information regarding local design plans and eliciting feedback and participation. In total, the architects produced twenty-two hours of prime-time programming with local network affiliates of both CBS and NBC.

-

Burns W. Roper, Trends in Public Attitudes Toward Television and Other Mass Media, 1959–1974 (New York: Television Information Office, 1975), 3–6. ↩

Read more

Chad Floyd, a young architect at MGH and a selfdescribed “TV native,” introduced the idea to televise the design process in a 1975 planning proposal for Dayton, Ohio’s downtown riverfront. Since voters had rejected the city’s earlier attempts to redesign the district, administrators stipulated that the winning design entry incorporate citizen involvement. Influenced by talk show host Phil Donahue’s innovative model of audience participation and the structure of 1950s and 1960s telethons, Floyd’s proposal eventually won MGH the Dayton commission and inspired the firm to incorporate participatory design initiatives in later projects.

Along with the televised Design-A-Thons, MGH designers encouraged public articipation by opening storefront offices in popular parts of town. These offices had large display windows and open-door policies that allowed locals to watch the architects at work and share their thoughts informally. During the impromptu meetings, designers would record ideas and display them in the office window to encourage further public feedback. MGH also set up formal design workshops with walking tours, role-playing sessions, plan-drawing exercises, and design reviews. Combined with the television programs, these methods comprised a comprehensive approach that made the design process as inclusive as possible. Over the next eight years, and with the help of the US federal government’s Urban Development Action Grant, MGH tested their participatory design method in five other cities: Roanoke, Virginia; Watkins Glen, New York; Springfield, Massachusetts; Indianapolis, Indiana; and Salem, Virginia.

Each Design-A-Thon was broadcast in episodes that corresponded to different phases of the design process, about thirty days apart. During the first episode, designers introduced themselves and the project before taking viewers’ calls. In the second episode, designers presented their initial design concepts and elicited feedback from viewers. After integrating public comments, architects proposed a selection of design models in the third episode. The final episodes constituted presentations of the recommended scheme with implementation strategies and development cost schedules. Local television station managers eagerly worked with the architects, going so far as to provide free airtime, because the design-a-thons satisfied a regulatory standard imposed by the Federal Communications Commission that stations devote air-time to “public interest” programming.

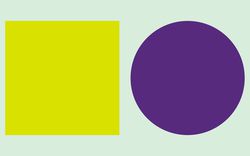

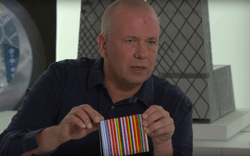

The staging of the Design-A-Thons, paired with the nearly instantaneous transmission of live television, turned the act of planning into a shared and public experience. To meet the unique demands of television audiences, Design-A-Thons turned architects into public figures, even showing them sitting at the drawing boards where they sketched out callers’ ideas in real time. Models were built and graphics were designed using bold, flat hues to ensure they would hold up under studio lights and transmit clearly over both colour and black-and-white televisions. Architects were required to adopt a casual tone while translating complex and jargon-heavy design concepts into language their audiences could understand. The programs intentionally depicted the design process as collaborative, exciting, and a little chaotic: phone banks opened lines of communication between designers and the public while caller suggestions were posted on studio walls and screens to visualize the influx of ideas. In reporting on the Design-A-Thons, Architectural Record referenced Marshall McLuhan’s concept of the “global village” and concluded: “Idea-by-idea, sketch-by-sketch, the people and their architects built up an image of their city as it should be.”1

Despite these promising initial steps, the potential of television as a medium for participatory design was curtailed in the 1980s with the defunding of urban projects and deregulation of broadcasting under the Reagan administration, which severely limited experiments in both planning and public affairs programming. Even more than political or industry changes, conservative professional attitudes and policies seem to have prevented many architects from turning to television. Floyd credits the biggest obstacle to its widespread use in design as “the straight-laced self-image architects seem to have of themselves.” When he tried to organize a design studio on the subject of television and participatory design at Yale University, Floyd found that “the majority of the faculty there viewed the topic as inappropriate.”2 The Design-A-Thons epitomized the social fervour of the 1970s, when architects and planners explored the mechanisms of pop culture to fulfill the mandates of social relevance.

This text originally appeared in The Other Architect publication in 2015.