As in an architectural project, the “place,” the form, and the method are carefully chosen and “designed” in order to intelligently relate the research topic to the available tools. The process, or how to reach some result—if one is desired—becomes a fundamental part of the project.

In the late 1950s, Constantinos A. Doxiadis was concerned with finding the right conditions from which to confront global ecological problems, the housing emergency, and the economy; he considered a week-long cruise in the Aegean Sea with an international and multidisciplinary crew to be the only adequate response. The first Delos Symposion was held in 1963, and the final one took place in 1975. Only by leaving the land, not being “anyplace,” and removing themselves from local problems could the assembled experts transcend individual notions of time and location to tackle pressing issues on a worldwide scale (“Informal gatherings”).

Anyone Corporation was founded in 1990 and declared itself to be “a new form of institution.” The emphasis on the indeterminacy of the word “any” and of its subsequent iterations in the form of conference titles—Anyone, Anywhere, Anyway, Anyplace, Anywise, Anybody, Anyhow, Anytime, Anymore, and Anything—along with a cadenced and precise idea of duration, which was set at eleven years in total, became programmatic instruments for establishing a productive climate for dialogue. The idea of time was a way of stimulating and gathering ideas through the repetition of one model in different places—separated from the development of content, in this case—but held to the same rhythm of conference and post-conference, with its epistolary exchange between participants and founder-editor Cynthia Davidson, and subsequent publication. By stimulating and gathering ideas, Anyone established a new platform for debate over the direction of contemporary architecture.

In other cases, the choice of place was essential for clarifying the research aims and effectively achieving the ambitions of these new institutions. ILAUD, for example, always occurred in an urban setting and usually focused on a historic centre. For De Carlo, Alison and Peter Smithson, and other participants, it was fundamental to engage with a real place and to have a shared experience there (“In Urbino certain things are more obvious”). But the place was also a pretext and a prompt to reflect on architecture; the project then applied shared tools of “reading”—that is, observing the city and recording its elements—and of “tentative design,” or proposing a project not as a definitive and feasible solution, but as a plausible scenario for further discussion.

The targeted choice of instruments in response to the context and to the problems posed makes these experiences illustrative of another kind of architectural operation. There is precision available in selecting appropriate tools, inventing them, or borrowing them from other disciplines—in other words, the architect’s cultural baggage when confronting a project.

The Atelier de Recherche et d’Action Urbaines (ARAU) and the Archives d’Architecture Moderne (AAM) both orbited the architect Maurice Culot in Brussels during the 1970s, when numerous projects threatened to uncritically and permanently modify the fabric of the historic city. ARAU proposed the “counter-project” as an active way of illustrating an alternative scenario and simultaneously involving citizens in imagining the potential of their city. Conducted in the same way as an architectural project, a counter-project visualizes the problematic aspects of the official design and illustrates a plausible alternative, creating a useful space for dialogue that goes beyond an act of protest.

The storefront component of Design-A-Thon developed this kind of public debate in another way. Moore Grover Harper’s choice of an office on the street literally placed architects in a shop window, which became a place for a new kind of dialogue that further enriched the diverse research and planning projects commissioned by city agencies. Regular workshops at the storefronts and an open-door policy allowed residents to learn about and participate in the planning process when they were done watching it on television (“In full view of passers-by”).

And if urban policy questions are the subject of a discussion, where better to display them than in the city itself? This was Melvin Charney’s choice for the exhibit Corridart, which he organized with the participation of numerous artists and collectives for the 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal. The entirety of Sherbrooke Street became the site of the exhibition, crossing the city from west to east, following a stratified panorama of affluent and working-class neighbourhoods all the way to the Olympic Stadium. The street became the three-dimensional background highlighting the contradictions of development in the context of the celebratory Olympic mood: a social housing crisis and the reckless demolition of historic buildings. Charney’s systematic and in-depth studies provided precious historical documentation of this Montreal “strip” and supported his clear and well-timed installation of the exhibit while playing with the communicative ambiguity of “taking to the streets.”

In their efforts to influence and reshape architectural practice, these groups also cannot help but experiment directly with whatever tools are available: televisions, buses, cameras, websites, theatrical performances, bulletins, fireworks, songs, surveys, games, letters—some of the many unusual apparatuses used to produce this new form of architecture.

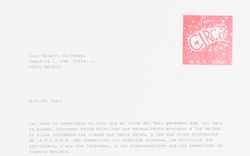

Monica Pidgeon discussed, recorded, and illustrated the ideas of the most important architects of the last century through an encyclopedic recording project that lasted more than twenty years: Pidgeon Audio Visual. She started the series because she believed in communicating architects’ ideas through their own words ; to understand what architecture was, one must listen to those who practised it (“It will look handsome…in addition to being useful”). She used a novel system of distribution for architectural publishing that allowed her to capture and combine words and images into slide-tape packs that were sold internationally to libraries, schools, and other institutions. More than just documents recording architects talking about themselves, the slide tapes represent a way of connecting architectural knowledge to a wider public. Using conversation as a tool to illustrate and recount ideas on architecture and the city has echoes in CIRCO, another publishing experiment. Spanish architects Luis Moreno Mansilla, Emilio Tuñón, and Luis Rojo de Castro launched a publishing adventure in 1993, in parallel to their practice. Twice a month they paused everything to publish the contributions of many architects of the moment in addition to their own writing. They developed an easy-to-use format of A4 sheets printed and folded in the office, distributing it just as simply and informally, through a circle of friends and acquaintances. Anybody could subscribe for free by sending them a postcard. This turn to the immediacy and the appropriateness of such a straightforward tool becomes a way to contribute to discussions about important topics beyond the walls of the office.

Observing the other architect moving away from the norm and inventing ways that architecture can construct a cultural agenda is also a way of asking how architecture can continue to be an intellectual field. It reminds us that architecture as a way of thinking does not lead only to architecture, and that despite its apparently intangible existence, this kind of architecture does not become less effective in spreading its intentions and conveying its ideas. In fact, the opposite is often true.

These case studies are only a selection from what could be a much larger a manual of alternatives. It is by imagining the possibility of a more articulate way of understanding architecture, and through reflecting on what architecture can be, that a wider field with more potential for action emerges.