Safeguarding Memory in Colonial India

Yakin Kinger explores the politics of commemoration

“At the Alam-bagh the site of Havelock’s grave was pointed out, and from one of the bastions I saw once more extended before me the gardens and suburbs of Lucknow—a fair scene in which lurked much mischief.” 1

-

Frederic John Goldsmid, James Outram: A Biography, Vol II. 2nd ed. (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1881), 300. ↩

The uprising of 1857–1858, which saw violent clashes between Indian and British forces, posed a severe challenge to British rule in India. In the uprising’s aftermath, the victorious British Empire undertook several measures to commemorate the loss of their military personnel. This took many forms, including erecting memorials and writing them into the land of the colonized. The Empire took active steps to counter the threat posed to their rule by the happenings of the uprising, constructing an image of the struggle as a resplendent series of events symbolic of British sacrifice, valour, and might in a far-off colony. These memorials were commissioned for the exclusive use of Europeans at sites of resistance in places such as Delhi, Lucknow, Jhansi, and Kanpur (then Cawnpore)—cities and towns actively involved in the revolution—thereby etching British history on these sites. The rejection of the insurgent’s place in history served as a colonial mechanism to safeguard the Empire’s narrative, and validated the simultaneous physical safeguarding of its memorials. By re-reading the colonial politics of commemoration enacted in spatial transformations in British India, we are able to look at alternate histories and processes of decolonizing spatial occupation after the country’s independence, thereby complicating our understanding of these palimpsestic sites of commemoration.

Memorials as Imperial Sites of Commemoration and Control

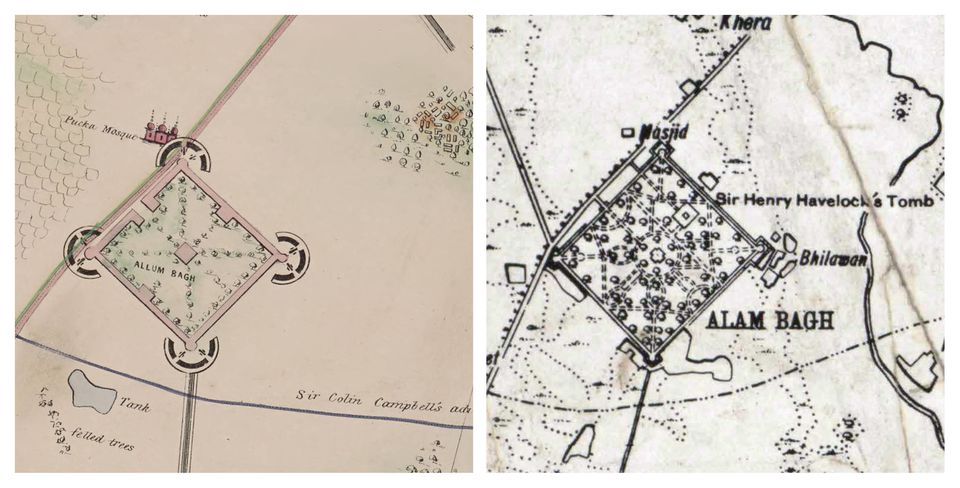

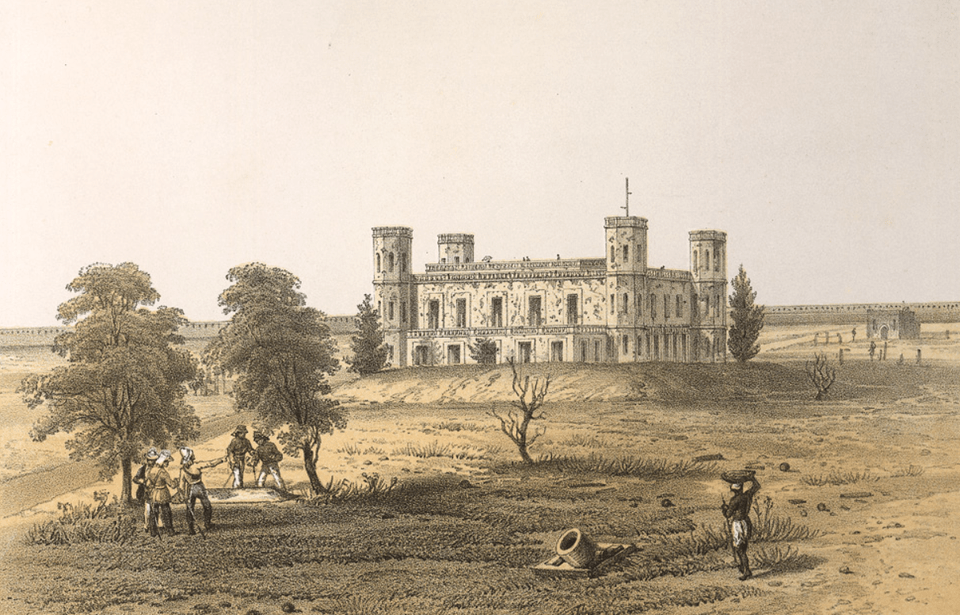

The insurgency in Lucknow under Begum Hazrat Mahal1 was a severe blow to colonial domination in the Awadh region. Lucknow’s multiple baghs (gardens) posed severe challenges for the British army in their attempts to recapture the region.2 One of the important sites that was strongly contested was the Alam Bagh, built by Lucknow’s last Nawab (King) Wajid Ali Shah for one of his wives.3 The Alam Bagh “… was admirably adapted [by the revolutionaries] for defence, as a strong lofty wall with turrets at each angle enclosed a garden about five hundred yards square, rich in flower and shrub, with a fine house carved with the numerous quaint devices of oriental taste in the centre, a mosque adjoining, and numerous offices for followers.”4

Alam Bagh was defended by trained, armed sepoys5—Indian soldiers who served under British rule. It had a strategic location south of Lucknow and on the way from Kanpur, another epicentre of the uprising. Thus, it was among the first sites to be recaptured by the British troops after a struggle on 23 September 1857. The Alam Bagh became the primary station for the British troops and supplies coming from Kanpur, also serving extensively as a depot for the sick and wounded.6 Its octagonal towers were used to communicate by telegraph with the Lucknow residency, an enclosure with many buildings and the seat of the British Resident General in Lucknow, besieged by the local forces during the uprising. Despite multiple attempts, the revolutionaries were unable to recapture the Alam Bagh.7

-

Queen of Awadh who revolted from her seat of power in the Qaisar Bagh in Lucknow. ↩

-

I have previously written about the history of India’s baghs and colonial power. See Yakin Kinger, “Undoing Empire: Rereading the Destruction of India’s Baghs,” Avery Review 62 (2023), https://averyreview.com/issues/62/baghs. ↩

-

Sidney Hay, Historic Lucknow (Lucknow: Pioneer Press, 1939), 77. ↩

-

G.W. Forrest, A History Of The Indian Mutiny, Vol II (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1904), 30–31. ↩

-

According to many accounts the uprising began as a sepoy mutiny against British rule. See Hay, Historic Lucknow, 78–79. ↩

-

Daroga Ubbas Alli, The Lucknow Album (Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press, 1874), 7. ↩

-

P. C. Mookherji, The Pictorial Lucknow (Lucknow: N.P., 1883), 159. ↩

Major-General Sir Henry Havelock, who was at the forefront of the British troops in Lucknow, died of dysentery in November 1857 on the grounds of the Dilkusha.1 His body was brought to the Alam Bagh, and Lieutenant General Sir James Outram asked for the grave to be leveled and marked to prevent the detection of its location.2 Precise measurements of the area were taken and a memorandum with its details was preserved in the archives of the government in Kolkata (then Calcutta).3 Later, within the Alam Bagh, a memorial was built in the memory of Henry Havelock.

Left: Plan illustrating the Report of Engineering Operations in the Siege of Lucknow by the British forces under General Sir Colin Campbell, March 1858. University of Minnesota Libraries, John R. Borchert Map Library

Right: City and Environs of Lucknow, 1862–1863. Military Department, Government of India

This clearly marked the British occupation of territory for the purpose of commemoration. While an early lithograph shows the grave in the shade of a tree within the ruined garden and with the palace in the background, a later sketch shows the memorial obelisk surrounded by a railing, like many other memorials of the time which were fenced, secured, and often inaccessible or restricted to the locals. Such measures completely transformed the royal leisure space into a site exclusively commemorating imperial loss, further preventing any possibility of the space harboring rebellion. This not only kept the memory of British sacrifice alive, but intensified it. With the erasure of any previous layers of history on the site came a shift in the perception of the place from Alam Bagh to that of the tomb of Henry Havelock. The removal of other spatial elements in depictions of the site engrained a singular image of the memorial in the British imagination. Controlling both depictions of and access to the site reinforced the exclusion of the city’s inhabitants and converted the real historical experience of the uprising into a construct protecting a part of British memory. The protection of the memorial was synonymous to the protection of British interests in the colony, ensuring that the will of the empire superseded those of its subjects.

Memorials in the British Imagination

In order for a landscape of memorials to become a part of the people’s conscience, it must be repeatedly reinforced through public consumption. To this end, memorials became part of the larger network of sites visited and re-visited by the British, including the Prince of Wales, who visited Alam Bagh in 1876. This reinforced the British claim on these spaces and suppressed any thoughts of their contestation. The safety of the memorials was ensured by such acts of regularly upholding and evoking the memory of the British loss of life.

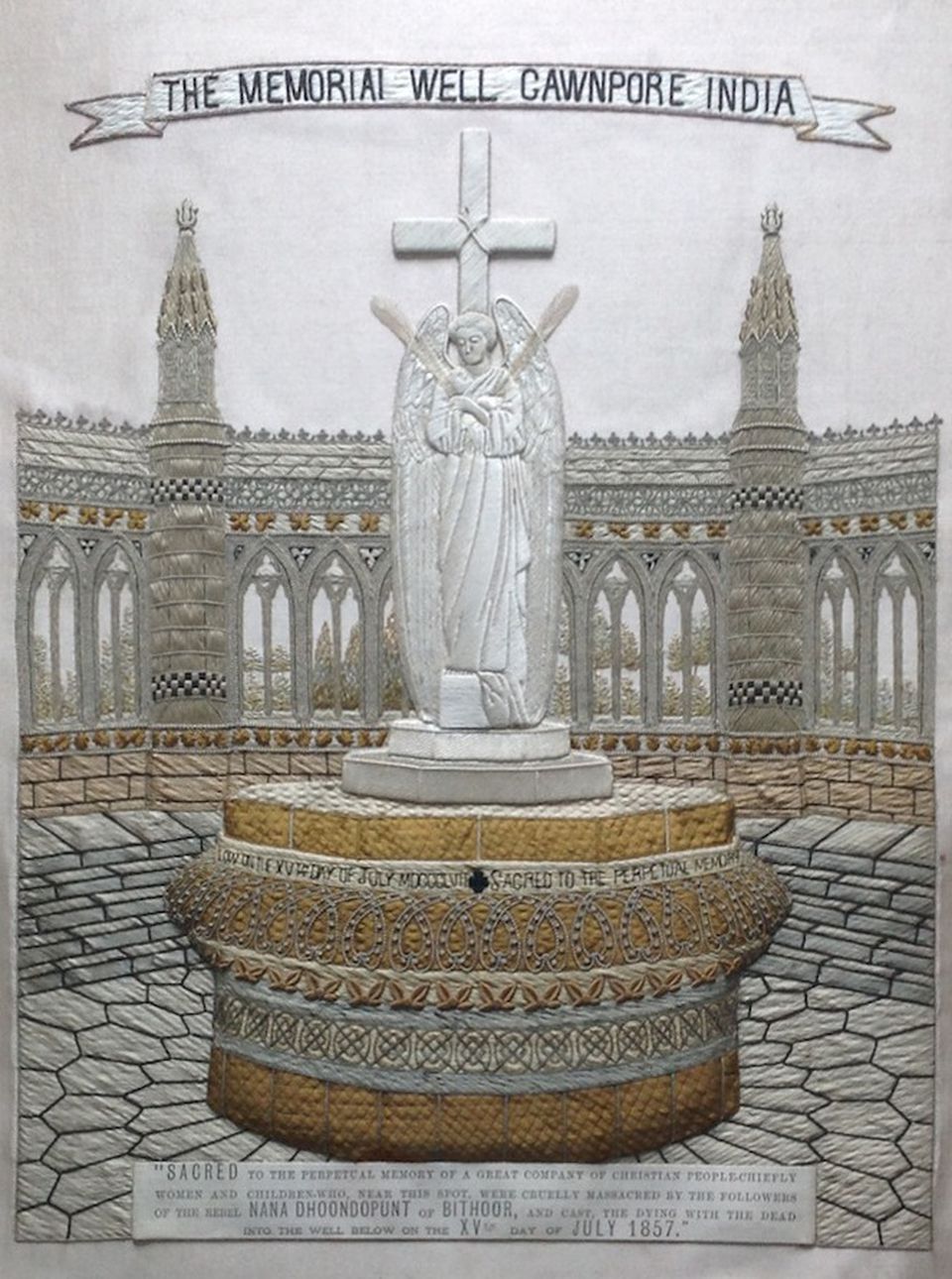

In Kanpur, the uprising took a significant turn on 27 June 1857 with the killings of British civilians by revolutionaries at the Satti Chaura Ghat, later deemed the “Massacre Ghat.” As the news of a British relief column arriving spread, captured British were also killed by the revolutionaries at Bibighar. These events are among the most prominent memories of the uprising etched in the British conscience, while the perspective of the revolutionaries remains largely absent in the archives. A memorial well was erected by the British at the Bibighar site, with the angel of resurrection as its centrepiece. In another instance, during the inauguration of a memorial in Lucknow, a newspaper noted that “about the center is a figure of an angel representing victory trampling down rebellion.”1 The erection of these symbols defined a new landscape of commemoration and imperial loss.

The expenses of building the memorial largely came from a fine levied on the Indian citizens of Kanpur, who were restricted from entering its compound2—one account recollects that “No native is ever allowed to enter this enclosure and they have to get passes to come into the Garden.”3 The memorial was opened in February 1863, and a British soldier constantly guarded it.4 This exclusion was also represented through architectural elements such as fencing. Memorials became a display of sheer imperial might and control, and their safeguarding acted as a colonial tool of counterinsurgency.

-

Pioneer (Allahabad, India), May 28, 1866: 4. ↩

-

Jan Morris and Simon Winchester, Stones of Empire: The Buildings of the Raj (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), 192. ↩

-

Marchioness of Dufferin, Our Vice-Regal Life in India (London, 1891 edn.), 218–19. ↩

-

Stephen Heathorn, “The Absent Site of Memory” in Indra Sengupta, Memory, History, and Colonialism: Engaging with Pierre Nora in Colonial and Postcolonial Contexts (German Historical Institute, 2009), 73–116. ↩

The memorial in Kanpur was frequented by Europeans visiting India in the few decades following the uprising, including the Prince of Wales in 1876. It was also visited by the Viceroys who took charge of the colony, ritualizing visiting similar memorials in Delhi and Lucknow. According to historian Stephen Heathorn, the memorial in Kanpur was more visited by Europeans in India than the Taj Mahal in the last third of the nineteenth century.1 The image of the memorial traveled through tourist sketches and found descriptions in traveller books.2 Its image also traveled across geographies through photographs and embroidered panels, and was included in exhibitions. The extent of media depicting the memorial across various mediums enabled its consumption among Europeans on a larger scale.

There is an absence of humans in a greater part of the media capturing these memorials. This cemented the monuments in the collective memory of the British as singular entities built by the Empire as a homage to their loss. Thus, the site at Kanpur also became an integral part of British imagination, erasing the presence of the local population on the site as well as in the media. The valorization of the Empire’s losses through its safeguarded memorials unquestionably allowed it to lay claim to contested territories. This overshadowed the possibility of any alternate account of the past and simultaneously negated the chances of any decolonial claim in the future. It formed a linear narrative of the sites as belonging to the British, while othering local populations from their sites and histories.3 The colonial state dominated the writing of history, subsuming Indian history in the process.4

-

Stephen J. Heathorn, “Angel of Empire: The Cawnpore Memorial Well as a British Site of Imperial Remembrance,” Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 8, no. 3 (2007). ↩

-

Morris and Winchester, Stones of Empire, 192. ↩

-

In employing the term “othering,” I am thinking alongside Edwards Said. See Edward Said, Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient (India: Penguin Books Limited, 2016). ↩

-

Ranajit Guha, The Small Voice of History: Collected Essays (Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2009), 341. ↩

Reclaiming Space and History in Independent India

Despite British efforts to erase counternarratives, alternate histories of the sites of the uprising were kept safe through modes including oral retellings, poetry, local newspapers, and claims by surviving stakeholders of the properties confiscated by the colonial administration.1 The British attempts at safeguarding their memorials as a counterinsurgency measure were undone when India gained freedom from British rule. The site of the Kanpur Memorial Well was vandalized on 15 August 1947, the day of India’s independence.

The loosening of British authority put in question the security and maintenance of British graves and memorials in the country. The attack on the Kanpur Memorial clearly indicated a rejection of a colonial remnant of imperial grief in an independent country. As elaborated by Indian historian Ranajit Guha, the Empire’s practice of exclusion had demonstrated “a refusal to acknowledge the insurgent as the subject of its own history.”2 Acts of vandalism and similar practices dictated the reclamation of these sites of memory. With independence came a desire to acknowledge these sites as sites of revolution, and not of imperial commemoration. According to Partha Chatterjee, a scholar of postcolonial studies, “Much nationalist thought in India depends upon the realities of colonial power, either in totally opposing it, or in affirming a patriotic consciousness.”3 The contestation of these sites by extension contested British accounts of the past and advocated for the acknowledgement of other histories.

-

For instance, the claim of Nawab Ikhlul Mahal to the Sikandar Bagh in Lucknow in the 1860s. Rejection of the claim of Nawab Ikhlul Mahul to the Secunder Bagh at Lucknow, Foreign, File no.: 51/53, Repository: 3, National Archives of India. ↩

-

Guha, The Small Voice of History, 235. ↩

-

Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (London: Vintage, 1994), 278. ↩

The Kanpur Memorial was relocated close to the Kanpur Memorial Church to avoid further attacks, and it resides there to date. The site of the Bibighar massacre was renamed the Nana Rao Park after Nana Saheb Peshwa II, who led the uprising in Kanpur. It was extensively transformed and now contains the statues of Indian revolutionaries who led the insurgency. The Empire’s layer of history was undone, replaced with the memory of the Indian leaders.

Though both the British and the Indian histories are interdependent, the rejection of one by the other led to the safeguarding of one against the other. The making and eventual replacement of the Kanpur Memorial shows this contradiction, where overlapping histories govern the physicality of the site and its interpretation. In the wake of independence, the decolonization of the memorial meant breaching its security and making its rejection visible. The active decolonization of the site defies the safety of the colonial narrative. This brings forward histories of the other, where the subaltern reverses the process of denying a place to the previously dominant history in its own rewriting.