Space Half Empty

Maroš Krivý traces how photography frames the potentiality of wastelands

“There is no such thing as an empty space,” my doctoral supervisor would quickly remind me anytime I brought up the topic of urban voids or wastelands. She was correct, of course. There is no empty space in capitalist economies, only processes of accumulation and devaluation through which capital is funneled into infrastructure and the built environment, then abandoned in pursuit of further accumulation. Emptiness mystifies—to claim that a place is empty ignores or obscures processes, conflicts, or histories through which it became such—and therefore justifies remaking the world in the image of capital, similar to how colonial expansion is premised on “improving” conquered territories. What capitalists and settlers share is their view of the world as a succession of retreating frontiers to be claimed. Yet what I was clumsily trying to get at was the significance of the wasteland as a historical category. For example, the wasteland has been understood both in terms of its landed relations and as a way of seeing space in terms of underlying interests in its use and development.1 In other words, emptiness can figure a tangible “social imaginary” to organize visions for the future: devoid of opportunities for some, full of promise for others. Considered in terms of spatial politics, emptiness is best approached historically as a category that justifies the imposition of values or functions on a place by claiming it has none.

One episode in the larger history of wastelands concerns the rhetorical, visual, and design strategies taken to endow indeterminate urban landscapes with positive meaning, as instances of “non-design.” Urban and design professionals have developed a fascination with urban wastelands and other residual landscapes as sites of alterity and potentiality. What opportunities and limits arise when these professionals advance a positive conception of emptiness to frame postindustrial change in cities? How is this imaginary shaped by their situatedness and positionality, as well as interests and affects? Taking us to Barcelona and Berlin around the year 2000, this text considers how architects used photography to reimagine the value of wastelands and other indeterminate spaces. I focus on two ideas that gained influence in architecture around 2000 when photographers alerted designers to the in-situ and unintended qualities of indeterminate sites yet also marked them out as sites of potential development, as architects began to mimic and exploit their “as found” aesthetics in acquiescence to postindustrial capital.

When I first encountered the term terrain vague, I was, like many future urbanists, drawn to the eponymous essay by Ignasi de Solà-Morales. Today, “Terrain Vague” stands out for its towering influence on architecture, urban studies, and related fields, marking a key means by which the term entered urbanists’ vocabulary soon after its publication in 1995.2 Solà-Morales imbued the French loanword with an affection for abandoned, ambiguous places lacking a clearly defined function within urban networks of productivity and circulation.3 Like many others, I failed to appreciate the context in which the essay shot to intellectual stardom, the issues that concerned Solà-Morales while developing the argument in the early 1990s, and the significance of photography in making his argument. By addressing these points, we can appreciate the opportunities and tensions marking the architectural appropriation of the concept of terrain vague.

-

Vittoria Di Palma, Wasteland: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014). ↩

-

Ignasi de Solà-Morales, “Terrain Vague,” in Anyplace, ed. Cynthia Davidson (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995), 118–123. ↩

-

The French term has a nineteenth-century provenance referring to a transitional space at the city’s edge, where farmland blends into working class suburbs. ↩

Solà-Morales presented the first draft of “Terrain Vague” in Anyplace, the edited proceedings of the meeting of ANY [Architecture New York] held at the CCA in 1994. ANY, or Anyone Corporation, was a platform for stimulating new architectural discourse through post-structuralist philosophy; Cynthia Davidson, one half of the New York-based architectural power couple with Peter Eisenman, was its brains. Throughout the 1990s, a group of some dozen core and many more occasional participants—including Rem Koolhaas, Phyllis Lambert, and Fredric Jameson—met annually in cities on four different continents, a jet-set venture enabled through the support of Japanese engineering conglomerate Shimizu. Solà-Morales’s sense of unease about the insularity of architectural culture, including his role in ANY, led him to enlist photography to defend the value of marginal, indeterminate sites.1

Interestingly, a full third of the brief, six-page essay is dedicated to recounting how “empty, abandoned space […] subjugates the eye of the urban photographer”. John Davies, Thomas Struth, and Manuel Laguillo were among those photographers through whose lenses Solà-Morales developed a fascination for what he called the “residual city”: urban spaces characterized by their historical continuity and future potential. Strangely, his essay in Anyplace is illustrated with a single photo of Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz taken by an agency photographer and depicting a still vacant square, albeit one already lined with looming cranes. In preparation for the publication, Solà-Morales sent Davidson a selection of images to illustrate his text, but Davidson went against his editorial instructions.2 The instrumentalizing emphasis the selected photograph places on processes of rebuilding—in the 1990s, Potsdamer Platz was dubbed the largest construction site in Europe, steps from where Eisenman would shortly make his mark with the Holocaust Memorial—lies in tension with Solà-Morales’s more expansive and nuanced perspective on post-industrial change. Significantly, the version of the essay published in the Catalan journal Quaderns d’arquitectura i urbanisme includes Davies’s suggestive photo of the Rotterdam Harbour: a terrain vague that is clearly not empty but a host to ordinary uses and everyday activities such as fishing.3

-

Solà-Morales played an ambiguous role in ANY as a member of the steering committee and the coordinator of the 1993 meeting in Barcelona, but also as something of a contrarian, wary of the group’s devolution into “a travelling circus of famous names.” Ignasi de Solà-Morales, “Anyletters,” in Anyway, ed. Cynthia Davidson (New York: Rizzoli, 1994), 200. ↩

-

Yasmine Sinno, “Solà-Morales’s Terrain Vague: Text and Contexts: Formulation, Dissemination and Reception: Perception and Intervention Processes at the Turn of the Millennium”(Ph.D. dissertation, ETH Zurich, 2018), 161. ↩

-

Ignasi de Solà-Morales, « Terrain Vague », Quaderns d’arquitectura i urbanisme, no. 212 (1996): 34-44. ↩

However, how far does a fascination with the residual city go toward questioning capitalist urban political economy? Another connotation of vague has remained unnoticed: the rounds of capital accumulation and devaluation that sweep through and transform places like so many waves. In this regard, Solà-Morales’s focus on the “potentially exploitable, expectant state” of land or territory stands out as problematic.1 For Solà-Morales, terrain vague initially provided a counterpoint and complement to Olympic-driven urban development frenzies. He above all had Barcelona in mind when he encouraged architects to pay more attention to the “strange world” of marginal sites, lest their profession become “an aggressive instrument of power.” 2 The 1992 Olympic Games marked a historical junction where post-dictatorship programs for reconstructing the Catalan capital were taken over by dreams of transforming it into a global city. During the 1980s, Barcelona underwent a massive transformation centred on large infrastructural projects and high-quality urban design. In the hands of Mayor Pasqual Maragall and planner Oriol Bohigas, the policy of restoring popular power through “re-urbanization” had given way to the emphasis on urban image and competitiveness. The building of the iconic Olympic Village and other neighbourhood-scale developments—where innovative architecture met a project to complete the nineteenth-century urban grid—was enabled by a close financial partnership between the public and private sectors.

Solà-Morales developed his concept of terrain vague in part by drawing critical attention to the unnoticed layers of the city revealed by photographs. In 1990, Quaderns d’arquitectura commissioned Laguillo, Davies, and others to document the Catalan capital in the build-up to the Games.3 These photographers provided Solà-Morales with an entry into the “strange world” at odds with the dominant imaginary leading urban development projects. Laguillo, for example, extensively photographed the El Poblenou area before it became an Olympic hotspot; although his concern was documentary, his images gave a sense of vibrancy to places deemed empty, mirroring the argument Solà-Morales made about terrains vagues.4 Pointedly, when ANY descended on the city, fresh out of the Games in 1993, Solà-Morales instrumentalized photographs to frame his reflection on architecture, violence, and the complicity of the discipline with colonial powers.5

However, because Solà-Morales never fully confronted the capitalist or socio-environmental dynamics underpinning terrains vagues, he leaned toward defining and defending their potential value in the narrow terms of the city’s image. Especially revealing is his overall positive assessment of the Olympic interventions, which he believed “truly created public space out of residual space” simply because they respected the nineteenth-century grid.6 The significance Solà-Morales accorded to the consensus between designers and public authorities around what he calls “the discreet charm of good manners” reveals a petty bourgeois emphasis on arbitrating good taste.7 In this case, the architect’s concern for urban visuality or legible urban design lies in tension with the photographer’s heightened attention to the texture of marginal places.

-

Ignasi de Solà-Morales, “Present and Futures: Architecture in Cities,” Thresholds no. 14 (1997), 24 [emphasis by author]. ↩

-

Solà-Morales, “Terrain Vague,” in Anyplace, 123. ↩

-

Jorge Ribalta, Universal Archive: The Condition of the Document and the Modern Photographic Utopia (Barcelona: Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, 2008), 85–86. ↩

-

Solà-Morales’s “Terrain vague” essay was in turn republished in Laguillo’s monograph, Barcelona 1978–1997. Manuelo Laguillo (Barcelona: MACBA, 2007). See also Sinno, 106. ↩

-

Ignasi de Solà-Morales, “Violence and Colonization,” in Anyway, ed. Cynthia Davidson (New York: Rizzoli, 1994), 116–123. ↩

-

Ignasi de Solà-Morales, “Letter from Barcelona,” Any 0 (1993): 60. ↩

-

Ignasi de Solà-Morales, “Barcellona alla fine del 1992,” Lotus 77 (1993): 126. ↩

John Davies, Berlin – Kteuzberg, Wilhelmstraβe, 1985. © John Davies. Courtesy L. Parker Stephenson Photographs NYC (top); Philippe Oswalt, Ecke Rosenthaler Strasse Gippstrasse, abandoned construction site, 1997. © Philipp Oswalt (bottom). Photographs in Urban Catalyst: The Power of Temporary Use, ed. Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer, and Philipp Misselwitz (Berlin: Dom Pub, 2013), 61

I came across another photograph by Davies in Berlin: Stadt ohne Form, a 2000 book by Philipp Oswalt (produced in collaboration with Anthony Fontenot and Rudolf Stegers).1 It depicts a tiny figure pushing a bicycle across a vast brache in Berlin’s Kreuzberg. The image, dating from before the reunification, is paired on the page with a photograph by Oswalt of an abandoned construction site in Mitte, emblematic of the erratic nature of the German capital’s post-reunification construction boom. The pair of photographs illustrates the chapter on urban voids, Die Leere: a key category among a series of experimental investigations around the idea of Berlin as a formless city. In the book, Oswalt explored the theme of urban emptiness through a range of cultural analogies, from John Cage’s silent piece 4’33’’ to the mystical doctrine that divine contraction is a precondition for divine creation, even quoting Rem Koolhaas’s quip that “where nothing exists, everything is possible.”2 However, aspects of the quotidian and the ordinary highlighted in Davies’s photo belie these grandiose analogies and pronouncements.

Oswalt’s photo (but not Davies’s) reappears in Urban Catalyst, a part-manifesto, part-research report that resulted from a three-year European Commission grant awarded to Oswalt, along with Klaus Overmeyer and Philipp Misselwitz, to investigate the role of what they called “temporary uses.”3 Between 2001 and 2003, the Urban Catalyst project, named after the collective the three architects formed in 1999, examined a range of informal activities on vacant sites. The value of these ostensibly empty sites was stressed in opposition to the program of critical reconstruction, a conservative paradigm for reconstructing Berlin based on nineteenth-century block-and-street urbanism and reimagined historical architecture. As an alternative to this dominant planning policy, marked by the adoption of the inner-city master plan in 1999, Urban Catalyst provided recommendations for enabling and exploiting do-it-yourself practices as drivers of postindustrial urban regeneration.

-

Philipp Oswalt, Anthony Fontenot, Rudolf Stegers, and Arbeitsgruppe Automatischer Urbanismus, Berlin: Stadt ohne Form: Strategien Einer Anderen Architektur (Munich: Prestel, 2000). ↩

-

Quoted in Berlin: Stadt ohne Form, 63. ↩

-

Philipp Oswalt, Klaus Overmeyer, and Philipp Misselwitz, Urban Catalyst: The Power of Temporary Use (Berlin: DOM, 2013). ↩

Urban Catalyst tied the value of voids to their potential role as “breeding grounds for innovations.” “Temporary users,” as Oswalt, Overmeyer, and Misselwitz claimed, value “personal visions” more than “political demands”.1 Saskia Sassen contributed an interview, in which she observed a close connection between terrains vagues and US-style maker culture.2 Kees Christiaanse, who provided the institutional home for the project through his TU Berlin professorship, prefaced Urban Catalyst by contrasting the confrontational culture of the pre-unification West Berlin to what he deemed the collaborative 1990s, which saw “capitalists and local activists” working side by side.3

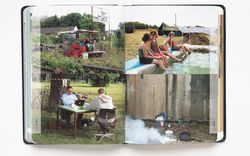

Oswalt, Overmeyer, and Misselwitz relied on photography to hammer home their point about the creative potential of urban voids. Urban Catalyst is punctuated with two sets of plates, one in black and white, the other in colour. Oswalt’s abandoned construction site photo features in the first set of black-and-white images depicting disused places without any visible human presence. Whereas Berlin: Stadt ohne Form was printed entirely in black and white, the use of black and white in Urban Catalyst functions as a foil for the lively colour-saturated images comprising the second set of plates. A sense of unease or tension about foreclosed opportunities is released as candid snapshots introduce us to the DIY culture flourishing in the city’s interstices: bars popping up amid disused railway tracks, a last-minute grant application put together in a haphazard outdoor area on decommissioned office furniture, and inflatable pools and portable smoke machines thrown in for good measure. The significance of routine activities to urban life, as is discernible in Davies’s photographs of the Rotterdam Harbour and Kreuzberg, is displaced by the colour images and their either/or emphasis on disuse and creative use. Marking urban voids with a sense of enterprise and entrepreneurial potential reflected and contributed to a broader cultural shift in Berlin: from Alternative Szene to the scene as capital.

The colour plates in Urban Catalyst echo the image of “poor but sexy” Berlin popularized by Mayor Klaus Wowereit (SDP) in 2003. Coinciding with the conclusion of the Urban Catalyst project, the slogan brandished by the social democratic leader emblematized the emphasis his political party placed on creative industries as engines of urban economic change.1 In 2004, SDP commissioned Oswalt, Overmeyer, and Misselwitz to survey more than 500 hectares of vacant space in Berlin. Urban Pioneers (2007), a white paper published by Berlin’s Senate for Urban Development, provided a framework for operationalizing temporary use as a postindustrial urban development strategy. “Urban pioneers,” the architects explained, generate a “financial stimulus” to the city through a combination of their “minimal capital outlay” and “a huge amount of personal commitment.”2 This was a “chance” for landowners, as Berlin’s Senator for Urban Development Ingeborg Junge Reyer (SDP) wrote in the preface to the report, to “realize the potential” of vacant spaces.3

A series of collages weaving through Urban Pioneers capture the double-edged role the architect plays in integrating creative work with capital accumulation. In a particularly striking double spread, photographs of DJs on decks and the iconic GDR-era Palace of the Republic are set against a series of clippings that juxtapose reports on “creative nomads” with headlines such as “The city lies empty [bracht]: 800 plots are waiting for investors”.

The concept of potential rent, referring to the rent a landowner could command if a plot of land had a “higher and better” use, is key to understanding gentrification. While gentrification studies interrogate the role of artists as agents and victims of capitalist displacement, the affective work of architecture and photography in anticipating or even promoting future rents has remained underexplored. While advocates of temporary urban spaces, from urbanists to photographers, voiced important critiques against a conservative urbanism that pandered to the image of Imperial Germany, visual history provides a murkier lens onto the alliance between architecture and postindustrial capital.

At the close of the twentieth century, photography acquired a heightened significance in centring the attention of architects and urban professionals on vacant lots, wastelands, and other urban landscapes that defy easy categorization into the built versus the natural environment binary. An architect may have once considered those sites as empty; now, in part influenced by images, they saw that they could be half full. However, acknowledging that a place is not empty while emphasizing its potential also primes it for rounds of speculative interventions. For Johan Andersson, building off the work of Rebecca Amato, “the association between terrain vague and “emptiness” or “wilderness” risks reproducing the colonial frontier imagery of gentrification.”4 The turn-of-the-millennium collaboration of architecture and photography has played an ambiguous role in this process: challenging the neo-modernist view of wastelands as blank slate sites awaiting improvement, while simultaneously framing a frontier imaginary by emphasizing their potentiality as sites of human and real estate capital accumulation.

-

Das Stadtentwicklungkonzept 2020 (Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung, 2004) marked a growing prominence of creative industries, urban competitiveness, and international real estate in Berlin’s urban development, as opposed to the formal dimension of critical reconstruction. ↩

-

Studio UC et Klaus Overmeyer (dir.), Urban Pioneers: Temporary Use and Urban Development in Berlin (Berlin: Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung & Jovis, 2007), 40. ↩

-

Ingeborg Junge Reyer, “Preface,” in Urban Pioneers, 18. ↩

-

Johan Andersson, “Berlin’s Queer Archipelago: Landscape, Sexuality, and Nightlife,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 48 (2007): 104; Rebecca, Amato, “On Empty Spaces, Silence, and the Pause,” in Aesthetics of Gentrification: Seductive Spaces and Exclusive Communities in the Neoliberal City, ed. Christoph Lindner and Gerard Sandoval (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021), 247–268. ↩