Fiction as Friction

A conversation on crafting resistance and solidarity between GRANDEZA STUDIO (Amaia Sánchez-Velasco, Jorge Valiente Oriol, and Gonzalo Valiente Oriol), Aude Christel Mgba, and Bruno Alves de Almeida.

- GRANDEZA STUDIO

- We would like to start the conversation by talking about friction. In our practices, it is something that is sought after (in the form of an institutional critique, for instance), but also sometimes our work has generated (un)expected forms of friction that we did not foresee.

In our 2019 project, Teatro Della Terra Alienata: Reimagining the Fate of the Great Barrier Reef, we faced this binary of friction. The work was the Australian Pavilion for the XXII Triennale di Milano, which called for “design (that) takes on human survival” amidst a planetary “broken nature.”

The film we presented in the pavilion looked at the drastic degradation of the Great Barrier Reef (a planetary symbol of ecosystemic exuberance) and the existing environmental, social, and political struggles taking place in the region, but also put forward the corrupt mismanagement of the reef by the Australian Government.

The script of the film envisioned the fictional secession of the Great Barrier Reef from Australia’s sovereignty enforced by the (also fictional) Xenofeminist International Corporation in alliance with the United Nations. The alienated territory would be incorporated into the (also fictional) geopolitical entity called ATAC (Archipelago of Territories Alienated from Capitalism). The work was a desperate and visceral call for attention on the plausible death of the Great Barrier Reef. However, we chose not to reveal some of the most controversial aspects of our investigation until the opening as we intended to generate some frictions or at least some healthy discomfort by addressing both the Australian Government and the Triennale’s audiences. Instead, the project received the Golden Bee Award for the best national pavilion. The work was celebrated, and it seemed that any effort of generating friction evaporated along the prosecco bubbles after the awards ceremony.

However, once we came back to Australia, we realized the project caused an (un)expected friction. We did not expect that the prize-winning pavilion at the Triennale would barely receive media coverage in its homeland. The cherry on top came after several meetings, screenings, and discussions about the project’s background, contents, and aspirations with a journalist from one of Australia’s most prestigious newspapers, who suddenly recommended that we should “tone down” the “tyrannical aspect” of the project if we wanted them to publish the interview.

We learnt two things from this experience. First, that it was not the facts, the analysis, or the denunciation of corruption and mismanagement we exposed that generated an ideological immune response in the country; instead, it was the political fiction we scripted. Within the current crisis of political imagination, a post-capitalist fiction was coined, literally, as “tyrannical.”

Could fiction be more powerful to activate critical conversations than simply presenting the facts?

The second thing we learnt was that reaching broader publics often becomes an odyssey for forms of dissident cultural production. You might agree that today’s multinational concentration of media outlets gives conservative forces extraordinary powers to mute and/or discredit research initiatives that challenge hegemonic mantras (such as resilience, sustainability, or smart cities).

What are the forces of friction that we could instrumentalize to expand urgent discussions beyond specialized audiences (to avoid the risk of enclosing our work within self-organized endogamic prisons)?

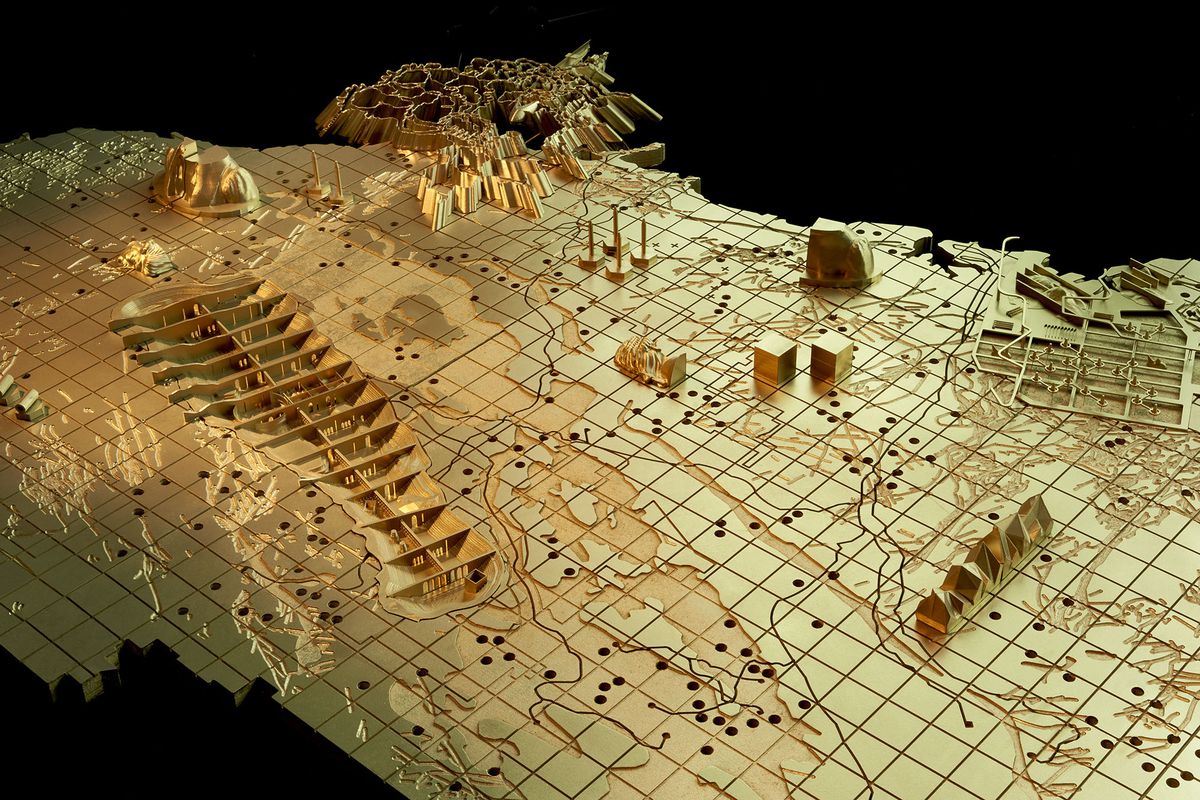

Grandeza Studio, Teatro Della Terra Alienata, 2019. Installation view as the Australian pavilion at the XXII Triennale di Milano, curated by Paola Antonelli. Creative direction and research: GRANDEZA STUDIO (Amaia Sánchez-Velasco, Jorge Valiente-Oriol, and Gonzalo Valiente-Oriol) and Miguel Rodríguez Casellas. Artists: Cigdem Aydemir, Liam Benson, Madison Bycroft, Shoufay Derz, Janet Laurence, and Patricia Reed. © Grandeza Studio. Photograph © Omar Sartor.

- BRUNO ALVES DE ALMEIDA

- Your experience with the journalist, and the notion that “fiction is friction,” has stayed with me. It prompted me to pull a book from my shelf: When Fact Is Fiction. Documentary Art in the Post-Truth Era edited by Nele Wynants. The book wrestles with the core question: “What is the value of fiction at a time when fake news, alternative facts, and others undermine the integrity of politics and media?” What does this mean for the critical traction that our work can generate?

As you’ve pointed out, friction is often intentionally sought after in curatorial and artistic practices as we respond to social and political urgencies. But we must be careful not to make friction an end in itself, a default goal to sustain relevance. In times of increasing institutional censorship and retrograde politics, we need to ask: Who is our intended audience? What kinds of friction are we actually generating, and toward whom?

I see the potential for this friction to create spaces of agonism, as theorized by Chantal Mouffe. Agonism fosters productive conflict between legitimate “adversaries,” encouraging debate rather than consensus. So, how do we craft sharp and critical messages that engage without alienating those with opposing views? How do we create agonistic spaces that invite dissent and expand our discourses beyond specialized circles?

Perhaps friction doesn’t always have to emerge immediately, but we need to let ideas take root and ripple out over time, allowing art to spark political imaginations long after the initial encounter.

I was inspired by how Teatro Della Terra Alienata built unexpected solidarities across contexts and opened spaces for questioning and connection. Fiction, in this case, didn’t just critique the system but connected with broader communities on an emotional level. It wasn’t merely about confronting power; it invited people to relate their experiences and aspirations through fresh perspectives.

Jenny Nordmark, SPRÄNGSTEN, 2024. Installation view at Havremagasinet länskonsthall i Boden (Havremagasinet regional kunsthalle in Boden) during the Luleå Biennial 2024 – On the threshold of 1:1. © Jenny Nordmark. Photograph © Thomas Hämén

- BRUNO ALVES DE ALMEIDA

- This approach resonates with our work for the Luleå Biennial 2024 - On the threshold of 1:1, which sought to connect Norrbotten, the northernmost region of Sweden, with other regions undergoing similar socio-spatial transformations. Norrbotten is often viewed as peripheral, but it is in fact at the heart of global processes that result in local drastic large-scale resource extraction, green-industrial transition, environmental shifts, and radical urban transformation, among others. Despite touching on very sensitive topics and processes happening on the ground, our curatorial approach also addressed these issues by connecting them to a wider context and bringing in voices and experiences from abroad, to open up new perspectives. As an example, your contribution to the Biennial Pilbara Interregnum: Seven Political Allegories, linked the Australian Pilbara to Norrbotten, showing how these distant regions not only share extractive processes, but also socio-political imaginations aimed at overcoming them. I believe the seeds planted there may bloom in time, even if they didn’t create immediate friction.

Maybe this more “stealth” form of friction, operating under the radar, can also help us avoid the trap of “self-organized endogamic prisons” as you’ve put it. Especially relevant in this era of polarization and right-wing populism, when there is an urgent need for dialogue, and new connections between ideas, people, and practices.

- GRANDEZA STUDIO

- Indeed, and your reflection makes us think of yet another urgent question: How can we challenge the apparent impossibility of creating solidarity in a broken geopolitical context?

We found the Luleå Biennial 2024 incredibly inspiring. Creating connections beyond traditional nation-state boundaries and across seemingly disconnected geographies with participants from Sudan, Palestine, Tindouf’s Sahrawi Refugee Camp, Sweden, Australia, and Finland (many of them often framed as “peripheral” from global centres). Your curatorial strategy was bold and effective in activating the conversation beyond the exhibition space and even beyond the limited duration of the Biennial itself. The installations transcended the boundaries of the Biennial’s venues and were distributed across railway networks articulating the region’s extractive apparatuses.

Commissioned for the Biennial, combustion/production by Daniel de Paula leaves a long-term footprint in Kiruna’s public space. The permanent metallic cobblestone formed by the fusion of metals from three sources: the LKAB iron ore mine, the Maria kapellet crematorium, and the city hall’s clock tower addresses the troubled relationships between slow forms of violence and deep time memories in the region and the associated forms of expulsion and exploitation of bodies and territories implicit in such processes.

It is remarkable how the artist managed to get the municipality, the mining corporation, and the crematorium on board; and we were wondering about the frictions hidden in the production of the work.

Daniel de Paula, combustion/production, 2024. Permanent artwork. Installation view at Kiruna stadstorg (Kiruna City Square). Commissioned for the Luleå Biennial. © Daniel de Paula. Photograph © Thomas Hämén

- AUDE CHRISTEL MGBA

- This has me thinking that for many of us in this world, friction can be a practice to reclaim one’s self or one’s humanity.

And here I want to reflect on the figure of the killjoy as developed by Sara Ahmed and from a queer and Black feminist perspective.

In a world that is shaped by oppressive binaries, hierarchies, and exclusion, it feels to me that friction is the only way some of us can pretend to have an equal existence. As a Black woman, friction is kind of intrinsic to my being and often a constant negotiation that I don’t necessarily seek, but in which I am constantly pushed in. Whether it is just the simple presence of my body, or through the position that I hold in my work.

What I really like with the killjoy is the refusal to be a subject or to be subjected. I have seen a lot of joy actually coming from that space of resistance. The will to create discomfort can be productive as it can generate new possibilities of thoughts.

For me, the critical question lies in how we navigate a world where some of us are already living in friction, while others may only encounter it or be confronted by it in specific contexts? How do we hold space for the killjoys?

I think some of the answers here could lie in comprehending that friction doesn’t always have to be explosive. Sometimes, it’s the quiet, slow, dark, and persistent that has the most transformative impact. As curators, we can cultivate spaces where friction becomes not just a force of critique but of connection, where those of us already living in friction can find solidarity and strength.

As a curator, I believe that I am responsible to hold spaces where friction is not feared but embraced. By holding space for those who refuse to soften the edges or erase their truths—we can push beyond the desire for easy consumption. - BRUNO ALVES DE ALMEIDA

- This conversation has helped me think of friction not as a binary but as a spectrum, varying in both the degree of disruptiveness and of individual agency. Artistic and curatorial processes often set friction in motion long before the audience engages, with effects lasting beyond the project. Similarly, the agency we enact as individuals—whether curators, artists, architects, or cultural workers—often begins long before the final piece is presented and extends beyond its completion. It’s important to reflect on how to leverage our distinct roles and possibilities while recognizing the limitations they may impose. Both Aude’s curatorial approach and Daniel de Paula’s site-specific work in Kiruna are examples of this.

De Paula’s practice is rooted in engagement with the site and its key actors, and his work reveals the social, political, economic, and historical forces embedded in material reality. In Kiruna, the involvement of and negotiation with such major stakeholders was also facilitated by the piece’s subtle yet layered nature, offering a clear message that is neither overtly political nor euphemistic. Rather than sparking immediate resistance, the work unfolds gradually, provoking deeper reflection over time.

As Aude noted, we as curators walk a fine line between artists, institutions, and stakeholders. Almost like a balancing act between challenging certain systems while also inviting them into new imaginaries. While sometimes, it’s about being accountable and holding space for the frictions already present in the lived experiences of those for whom friction is a constant reality. I think it’s useful here to expand the idea of “curating” by introducing the concept of “the curatorial.”1

I believe the principles and modes of operation that “the curatorial” holds could provide food for thoughts in the field of architecture. Architecture often is so entangled in political and legal forces, and fragmented between design and construction, which can dull its ability to take a critical stance. Yet, it’s inspiring when architectural tools are expanded to engage with other spheres, creating critical friction.

In your work Grandeza, I see the expansion of conventional architectural tools/thoughts to engage with pressing questions that extend beyond the discipline’s confines. I am curious to know what “the curatorial” could mean in your work, which hybridizes art, architecture, research, critical spatial practice, writing, design, filmmaking, pedagogy, and curatorial projects, such as the recent Espejito Espejito (Mirror Mirror) for the Mayrit Biennial 2024. - GRANDEZA STUDIO

- Aude’s statement on friction as “the only way some of us can pretend to have an equal existence” and Bruno’s concept of the “slow release of friction” deeply resonate with our concerns and recent experiences. These ideas prompt us to reflect on how friction shapes safe spaces for those subjected to constant societal “othering”—through race, gender, sexuality, class, and ideology—while forcing us to question who defines the thresholds of tolerance for friction in cultural and intellectual spaces. This ongoing tension occupies our thoughts as we present our work to institutions that hold the power to make or break our projects.

This compromise reflects a broader issue: neoliberalism’s infantilization of audiences.2 In reality, as Aude pointed out, friction is inevitable and unevenly distributed. Cultural institutions have encoded this into their norms, ensuring that certain kinds of friction—especially those challenging white-patriarchal-capitalist supremacy—are framed as threats, as “radical,” as ideological manipulations, or as unrealistic and anti-pragmatic fabulations.

This raises crucial questions about audiences’ tolerance for friction. Should we self-moderate to avoid alienating those conditioned to reject “radical” discourses, or should we push forward, unapologetically? Who are these alleged audiences? Who defines the thresholds of sensibility? When does friction turn into violence, and when does it act as a destabilizing force? When is radical fiction violent and when is it not?

Our time demands urgent and, sometimes, visceral responses. Yet, Western cultural institutions remain complicit in softening narratives to placate conservative donors and maintain the status quo. Neglecting structural forms of violence while toning down the artists that viscerally react against them might only exacerbate the current generalized sense of impotence in the face of unfolding crises. Instead, art should grasp the roots of those reactions, put them in the centre, and embrace them as fundamental forces for an effective decolonial shift. - AUDE CHRISTEL MGBA

- The more I read our conversation, I am convinced that the possibility of art to cross boundaries and create spaces is the reason why we operate within this realm.

The methods that artists and curators use and create have the potential to produce alternative trajectories and stories. And when it comes to projects such as Daniel De Paula’s, I think it is a great opportunity to reflect on the question of reparation—what it means, what it looks like.

And here I am thinking of hijacking, repurposing, redirecting, and transforming resources—both material and symbolic—produced by violent systems of exploitation. This approach of hijacking does not confront institutions directly, but it can transform their systems by redirecting their resources to people who usually never benefit and create noise.

I see a strong value in this nuanced tactic. But because I question my own positions, I wonder if hijacking can escape the frictions it seeks to subvert, or is there a risk that it just reinforces the systems it criticizes?

-

The concept of “the curatorial” is explored in these two examples: First, Irit Rogoff in “Smuggling” – An Embodied Criticality (2006), states: “In the realm of ‘the curatorial’ we see various principles that might not be associated with displaying works of art; principles of knowledge production, activism, cultural circulation, and translations that shape how art can engage.” Another definition is from Maria Lind’s 2009 Artforum text “The Curatorial,” where she describes it as: “…a more viral presence consisting of signification processes and relationships between objects, people, places, ideas, and so forth—a presence that strives to create friction and push new ideas.” ↩

-

This a theme is explored by thinkers like Mark Fisher. Although we don’t fully align with Fisher’s characterization (as we find a lot of matureness in certain aspects of children’s “naïve” political worldview), it’s undeniable that decades of concentrated media, capital, and neoliberal discourse have created an aspirational consensus that friction is uncomfortable—a problem to avoid. This is the myth sold to the public: that friction’s (and fiction’s) potential to “affect certain sensibilities” threaten institutional harmony in “a diverse world” and should be downplayed. ↩

- GRANDEZA STUDIO

- Working with and within the infrastructural and institutional frameworks we seek to put into question (materially, epistemologically, symbolically…) is both a problematic and necessary endeavour.

Indeed, your question, Bruno, about Espejito Espejito is a timely question to bring forward another story.

As you know, this year, we curated an exhibition at Madrid’s Museo de América for the Mayrit Biennial 2024. For some context, the museum was created in 1941 (during the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco), to celebrate the “epic” narratives of the Spanish empire. We decided to curate a dissonant, syncretic, and transversal display of existing works, new works, performances, and spatial interventions by artists from African, American, and Iberian diasporas to collectively imagine decolonized and de-binarized “New Worlds” that confront the Eurocentric legacy legitimized by the museum, while challenging its discourses and speaking to its collection.

One of the invited artists, Juan Covelli, had been working for several years on a critical and speculative body of work around the Quimbaya treasure—a set of gold and tumbaga objects created by the Quimbaya Indigenous Peoples (in today’s Colombian territory). Nowadays, these objects are probably one of the most controversial sets of pieces amongst the Museo de América’s collection.

While assembling the exhibition and Covelli’s work (which included, inside a display showcase, a replica of the Quimbaya treasure made by a Filipino goldsmith in the seventies that the museum lent Covelli for his artwork), the Colombian Government officially requested the repatriation of the original Quimbaya treasure from Spain. In response to the escalating tensions, Covelli included a note in the display stating that the original Quimbaya treasure was still retenido (a Spanish word suggesting “unrightfully held”) in the museum.

In response, the museum directors decided to incorporate a “counter-sign” nearby Covelli’s work indicating that the museum did not necessarily endorse (or agree with) the artist’s nor the curators’ point of view, and the Colombian Government’s request for repatriation was not legitimate.

For us, having the museum write a “counter-sign” contradicting the discourse of a work they were also safeguarding and exhibiting was already symptomatic of the ongoing transformation of the museum. For a moment, the museum was rendered as a space in which conflict is made visible and conflicting visions can converge. As Bruno put it before, it felt like an agonistic space that invited dissent and from which expanding our discourses beyond specialized circles seemed possible.

Some days after, they added a similar sign at the beginning of the exhibition stating that patrons could find offensive some of the contents of Espejito Espejito. “For whom” is a specific discourse, aesthetic, or content “unpalatable” and for what reasons? And for whom should cultural institutions represent a safe space freed from violence?