Waste Creeps Back

An interview with Curt Gambetta

- CCA

- It is typically the “ruptures or discrepancies” of waste infrastructure that are seen as signs of failure, which in the context of Imperfect Health also means that they are dangerous. But are there public health implications for the uninterrupted flow of waste as well? Can hiding waste be “bad” for us?

- CG

- When I think of the consequences of hiding waste, I think first of its political and the social implications. Questions of health are struggled over and inseparable from social experience. I am most interested in how questions of health are contested in the messiness of everyday life, whatever their supposed enclosure in the domain of science and technocracy. The implications for public health are in many senses an outcome of the way in which we organize our relationship to waste—socially and spatially. It is inscribed at the heart of notions of public and private responsibility as well as architectural and urban order.

I think it is important for design culture to acknowledge that many of the conventions that underlie the contemporary architectural imaginary (liberate the groundplane! re-enchant the sensory!) are in fact old dilemmas which owe much of their inheritance to sanitary debates in the nineteenth century. The “cleansing” of the gaze and the divorce of the visual from other sensory experiences of the city and space are also significantly intertwined in efforts to manage society’s relationship to waste. More prosaic conventions such as mapping, now part of the DNA of architectural pedagogy, also originate in the work of sanitarians in this period. Architectural and urban thought continues to operate in the shadow of this legacy.

Exposure and contact with waste is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, contact with waste (for our purposes municipal garbage) is indeed harmful, and it is no secret that much of the wasted matter that we produce will emit toxins and other by-products as it decomposes and interacts with the environment. Society simply cannot live in close proximity to much of the waste that we produce today, though the location of dumping frequently exploits marginalized communities in the United States and abroad. At the same time, waste also comprises a key resource for marginalized communities. “Hiding” waste can thus restrict access to its status as a resource.

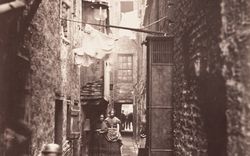

Urban India is an important case to consider, precisely because cities in India are under a good amount of internal and external pressure to adopt systems of waste management akin to what takes place in the US: door-to-door collection, centralization of waste into landfills, and collection facilities held by large corporations. Thus far, this model has been somewhat of a failure, though it is still establishing itself. Extra-official transactions and dumping occur in many forms and sites throughout cities such as Bangalore, making waste available to appropriation by economies of collection, recycling, and reuse that are distributed across a socio-economic spectrum of scavengers, drivers, dealers, and factory owners, among others.

In opposition to the model of contracting waste management to large corporations, as is unfolding now in cities across India, value is distributed throughout the city and is decentralized, rather than centralized in the landfill and in the coffers of a large corporation. For now, the porous, distributed economy of collection and recycling is resilient, but the long term consequences of this new model are yet to be seen. In closing the “avenues of participation” that the current system allows for, we are in effect pulling the rug out from underneath the livelihood of a significant number of people, not to mention closing down the possibility of productive economies of recycling and reuse.

When we disappear waste, we remove it from the possibility of political contestation. Much of the environmental movement knew this well. The recycling movement in the US, which I grew up with in the 1980s, was about producing consciousness about the consequences of waste-making. The unstated problem was that the “out of site, out of mind” mentality was in effect supported by an increasingly centralized and privatized infrastructure of waste management. This system remains designed to disappear waste and its by-products as efficiently and quietly as possible.

What I find limiting about the morals of the recycling movement was that it relied largely on individual responsibility to effect change. What the NIMBY wars over toxic dump sites and landfills made clear was that small acts of wasting always affect other people and life forms (unfortunately, this has historically been a burden placed disproportionately on the poor and marginalized). Waste is an unavoidably collective and public dilemma. It always manages to escape the physical, legal, and economic enclosures that are constructed around it. Anyone who lives near a landfill deals with this daily: smells and even toxins do not stop at a property line or boundary fence.

Relying on the ideal of an individual, unhindered citizen as the locus of change is problematic in light of the fact that questions of consumption and waste-making are anyways too big for an individual to comprehend. I learn from the philosopher John Dewey in this regard: rather than vilify interest—as progressive politics is wont to do—interest is everything. Collective experience is in large part generated by things that interest us and affect us. It is impossible to know everything that crosses our path on a daily basis…there is too much information to make sense of. A public comes into being when there is sustained interest in an issue or dilemma. No issue and no interest equals no public.

Bodily health is a great example of this: there is an overabundance of information about many ailments. I personally find it dizzying. If the task of public life, in Dewey’s mind, is to turn sensations into perceptions, I wonder, how do we sense these issues in the first place? After all, our bodies are dumping sites in miniature for all sorts of chemicals and toxins (a twist on Koolhaas’s assertion that our bodies are little construction sites of junkspace). Even our DNA is “junk,” as Thierry Bardini has written about recently.

Hiding waste assures that contestations over responsibility and power are left off the table. Removed from the political and framed as a problem of “management” and technology, waste infrastructure remains unpredictable and volatile. Waste creeps back into our lives and bodies. Think of pharmaceuticals in drinking water, or leakage of airborne by-products and leachate from older landfills and dump sites. Can waste ever be a purely technical dilemma, in this context? Hiding waste is a bit of a contradiction, since hiding is premised on the fact of its visibility. Contestation about waste happens wherever the effects are felt and experienced, effects that are often invisible. It is present even when it is hidden.

Architecture continues to fall largely on the side of the technical fix, with some notable exceptions, in response to the consequences of waste-making, whether in the design of facilities or the innovation of recycled materials. Critical responses fall around two potential strategies.

One response to the pervasiveness of these effects is to make visible what is already present in our daily lives and bodies—that which we feel and which affects us. Design is a “feeling aid,” not just a didactic mechanism, in this sense. It operates at the level of sensation as well as perception, investigating how interest can be produced around something, like waste, that is difficult to even feel or conceive of. Second, I think it is also important to understand where waste is already made visible—where it is already critiqued, politicized, or made productive for different economies. How can design practices collaborate with already existing forms of critique, expertise, and innovation?

We wrote to the architect and researcher Curt Gambetta in 2012, in the context of our exhibition Imperfect Health.