James Burgoyne Photographs the Streets of Birmingham

Text by Alice Gavin

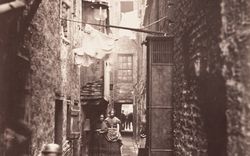

Initiated in response to the Artisans’ and Labourers’ Dwelling Improvement Act of 1875, the Birmingham Improvement Scheme saw the radical revision of an urban region spanning two central wards: veering slums were torn down (with dubious efforts at rehousing their inhabitants), and a sweeping “Parisian boulevard,” called Corporation Street, was constructed. In advance of these transformations, the Town Council–appointed Improvement Committee commissioned a series of photographs. Taken by James Burgoyne, whose photography studio was located on the Coventry Road, these photographs depict the oozing streets and skinny alleys no longer considered appropriate to an ambitious industrial town whose motto was “Forward.”

Collected in the archives of the CCA alongside comparable series, such as Thomas Annan’s photographs of Glasgow taken for the Glasgow City Improvement Trust in the 1860s, Burgoyne’s images do not simply document. They also actively participate in a process of obliteration. Constantly conscious of possibility, of prospects in all meanings of the word, their purpose was to record the town in order for the Improvement Committee to reassemble it. Accompanied by a map indicating their specific sites and locations and camera angles, the photographs were intended to be almost immediately obsolete, yet simultaneously to operate as a functional tool for spatial knowledge. In this sense, Burgoyne’s camera does not merely capture old Brummagem: it also exposes the possibility of a new Birmingham, pointing out where it will go, what it will oppose itself to.

In one photograph of a series of thirty-six, number twenty-nine on the map, the image is arranged to frame a squeezed passage known as the Gullet. On either side stand a pub, the Hope and Anchor, and a furniture depository. It is, though, the Gullet’s crooked gap that the composition emphasizes, to the extent that it seems as if the image itself is being snapped in two, cracked and fissured by its subject. The Gullet becomes not simply a good example of the narrow streets the Improvement Committee sought to eradicate; it is also presented as an urban feature with the capacity to fracture, dishevel, and disorganize of its own accord. Burgoyne’s pedestrian-eye-view, a position maintained throughout the series, is crucial in pointing this out.

In another photograph, number six on the map, we see a street entirely emptied of human inhabitants. But Little Cherry Street is not yet defunct. It is home to both J. Pullar and Sons and a W. H. Hart, provision broker, with both businesses occupying buildings whose brickwork is sturdy. Yet, this is again a photograph composed of two halves. On the left stand the sound structures of J. Pullar and Hart, while on the right, at once foregrounded and at the same time shrunken by its neighbours’ scale, is a structure slipshod and crumbling, its facade plastered with advertisements for “cheap excursions” to suburbs such as Sutton Coldfield. In other photographs, we see advertisements for migrations further afield and more irreversible: signs outside a shop tell of “assisted passages” to Canada with the promise of free grants of land and of boats leaving Liverpool for America every Thursday. In combination with notices representing buildings as “Lot 3” and “Lot 4,” these printed additions to the architecture announce a town that is, very literally, taking leave of itself. Burgoyne’s photographs do not only preserve and document; they also expose the streets they observe to what is to come.

Alice Gavin conducted research here in 2012 as a recipient of a Support Grant.