The Tuberculosis Sanatorium of Paimio

Text by Eva Eylers

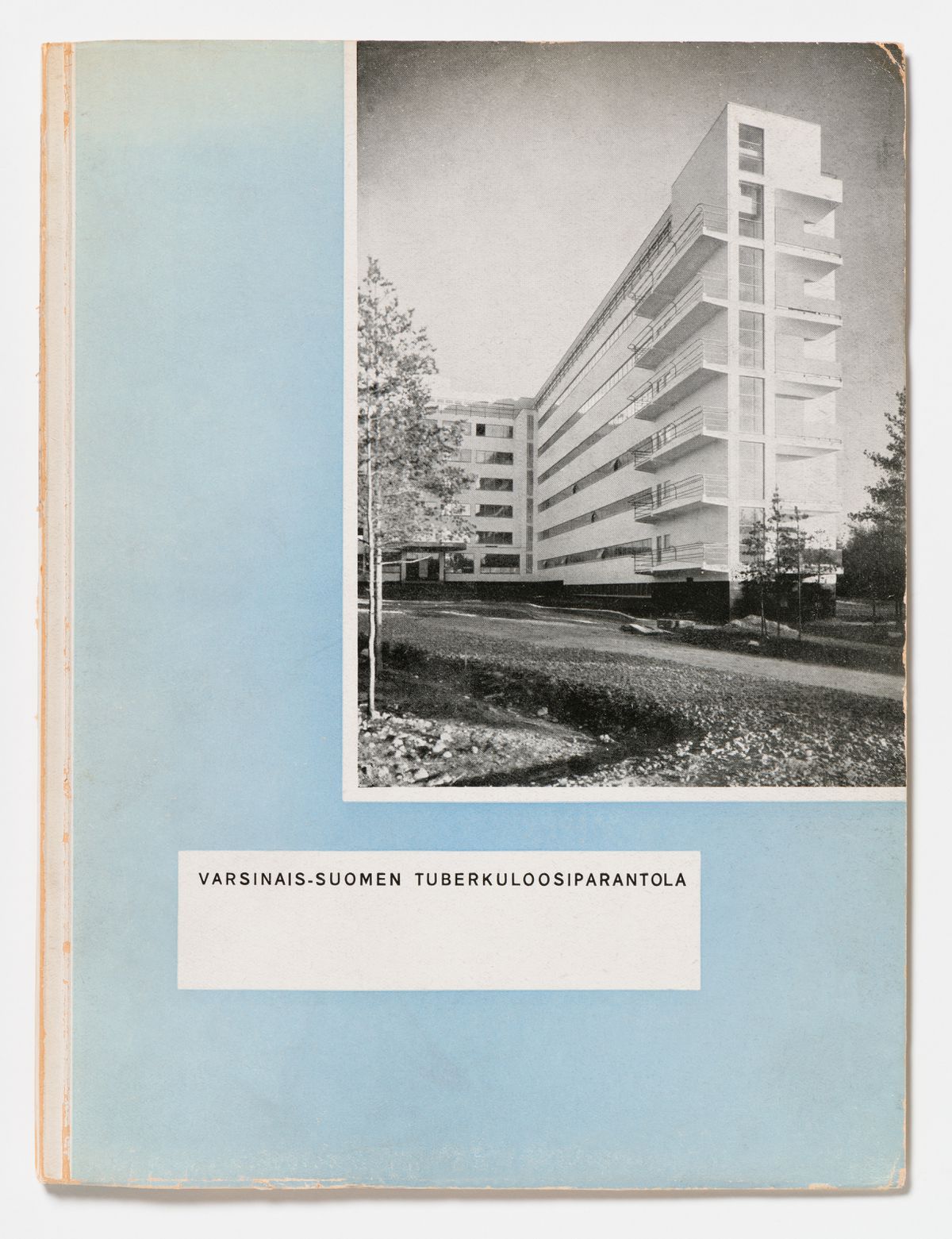

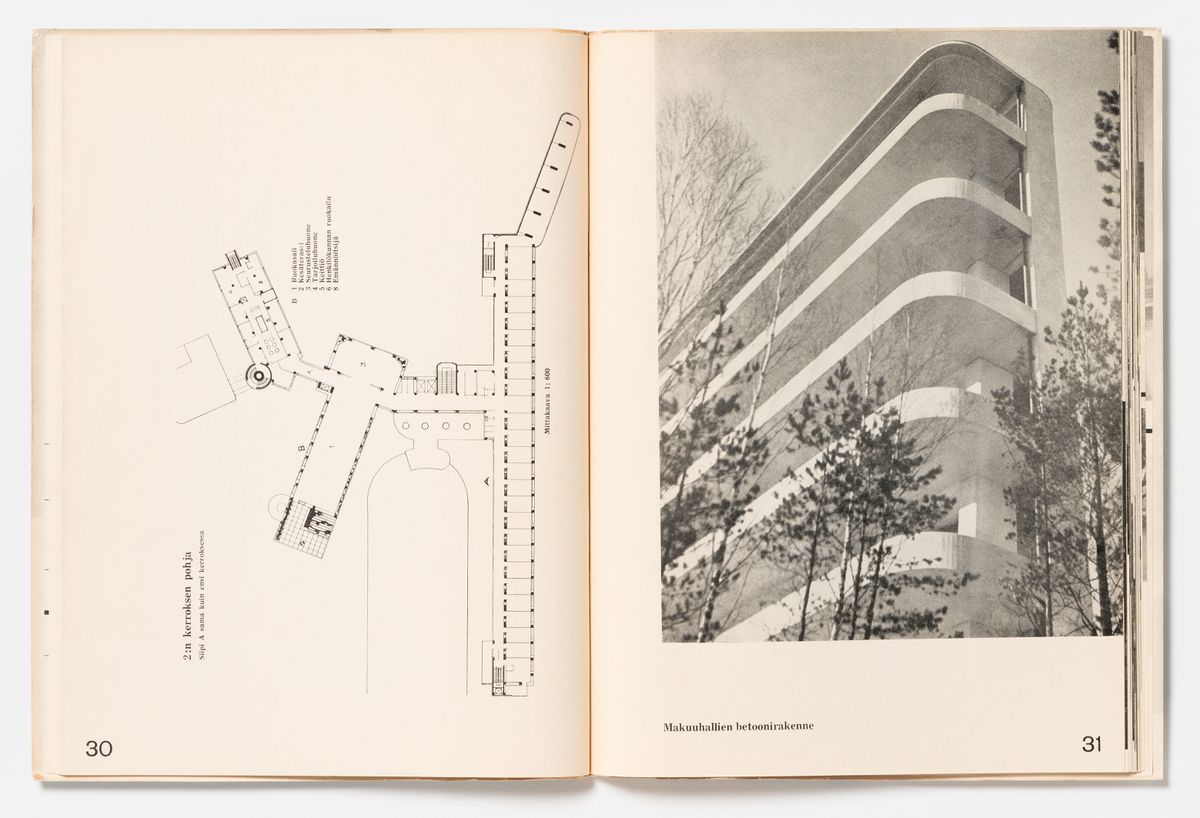

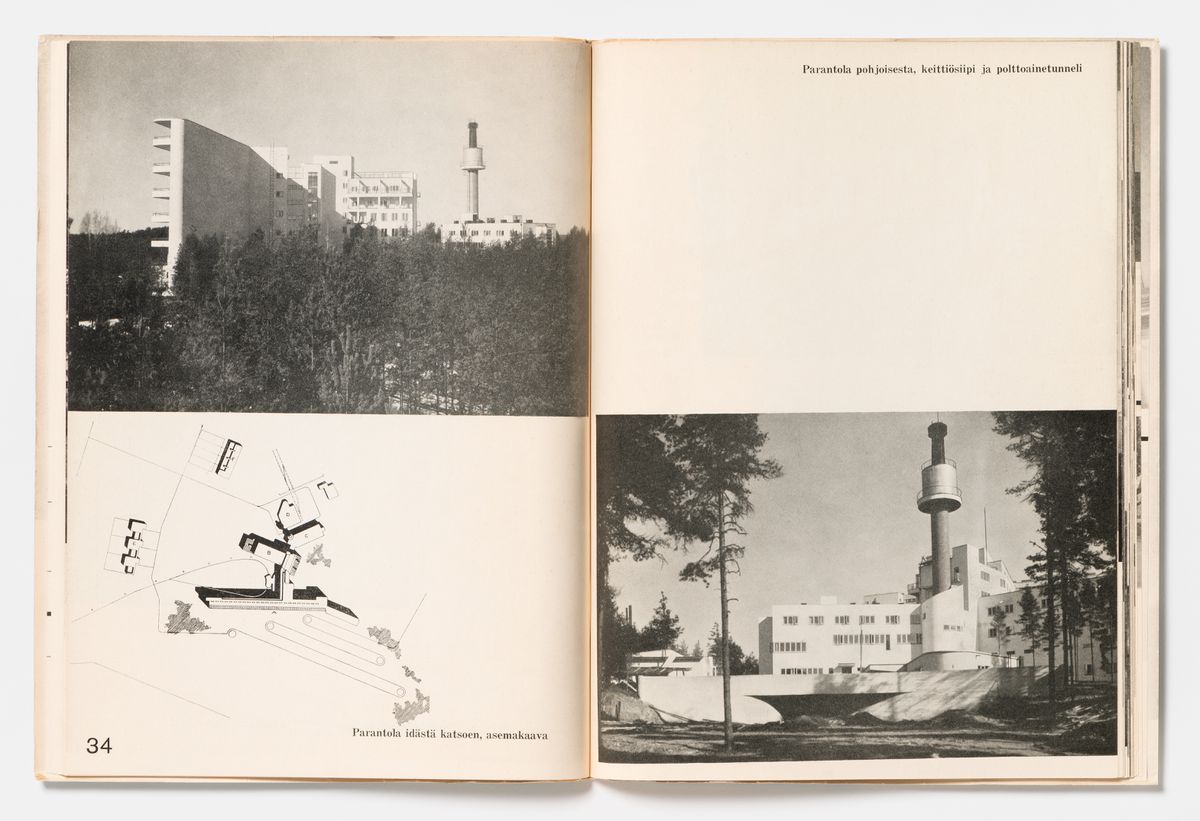

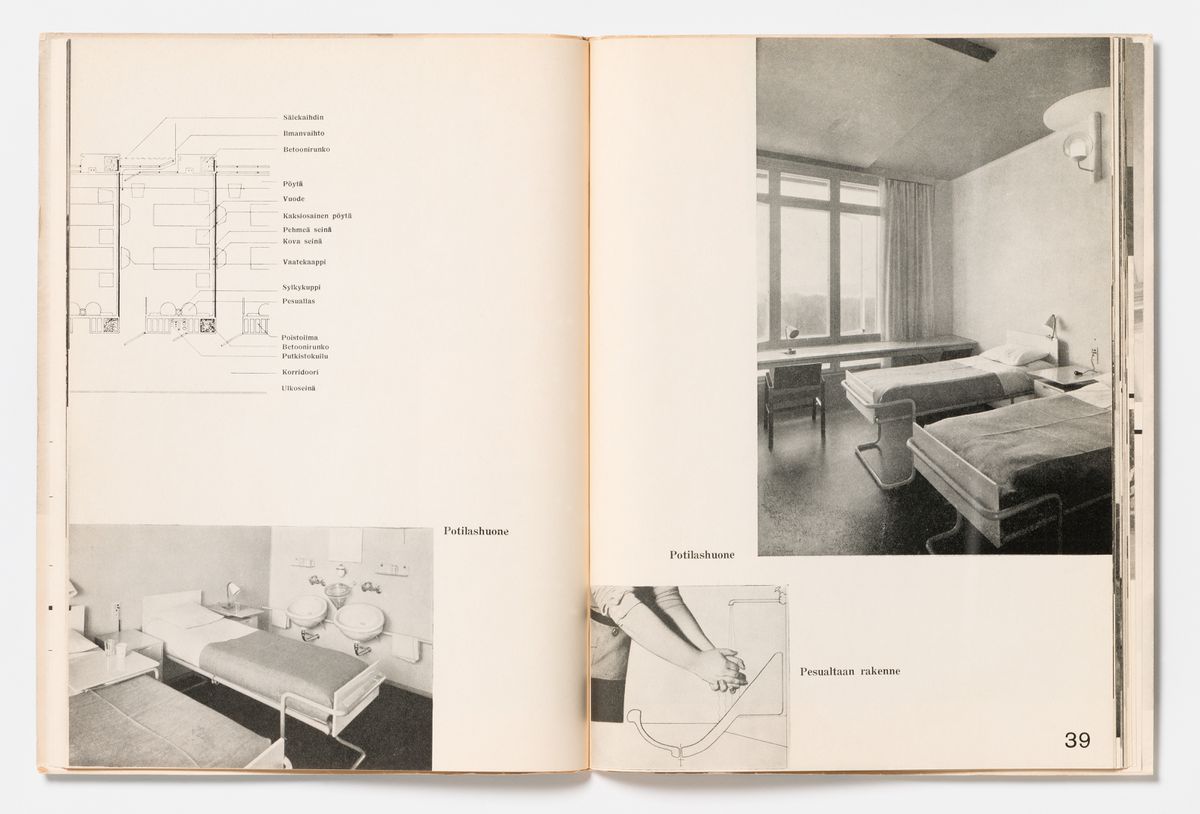

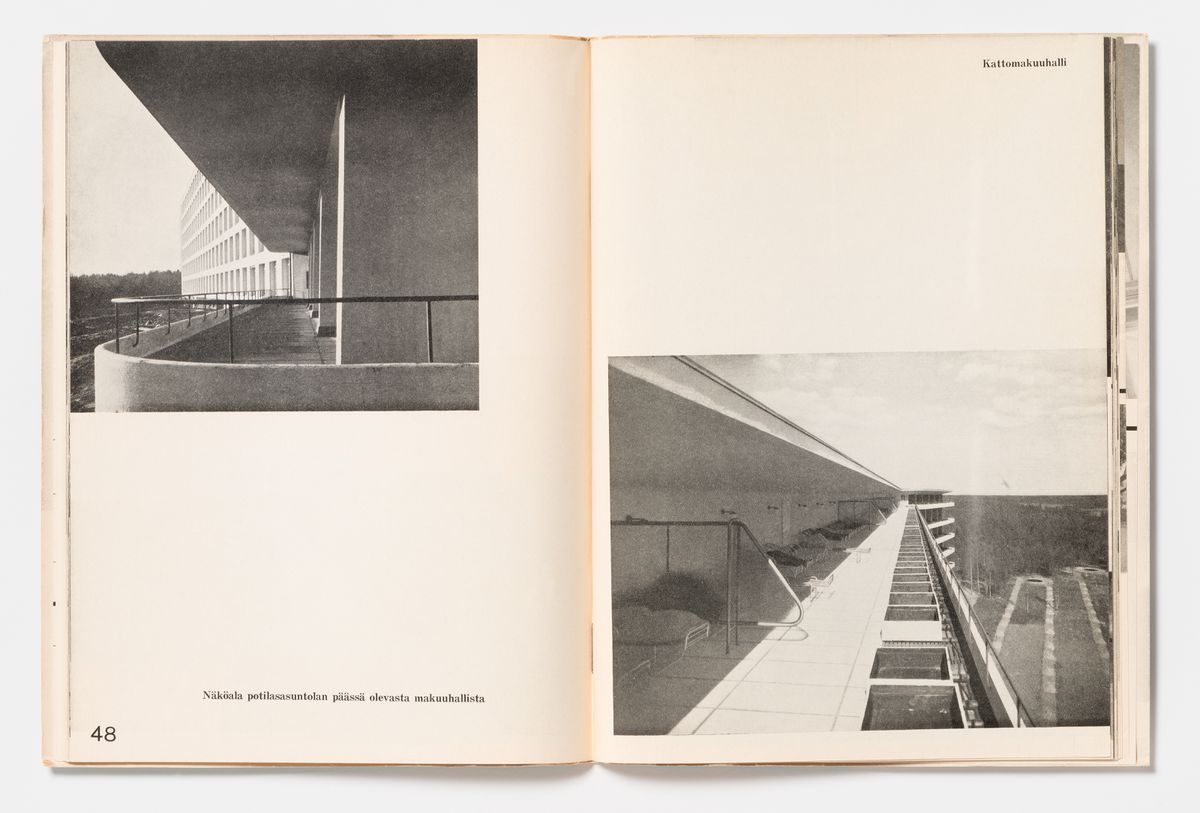

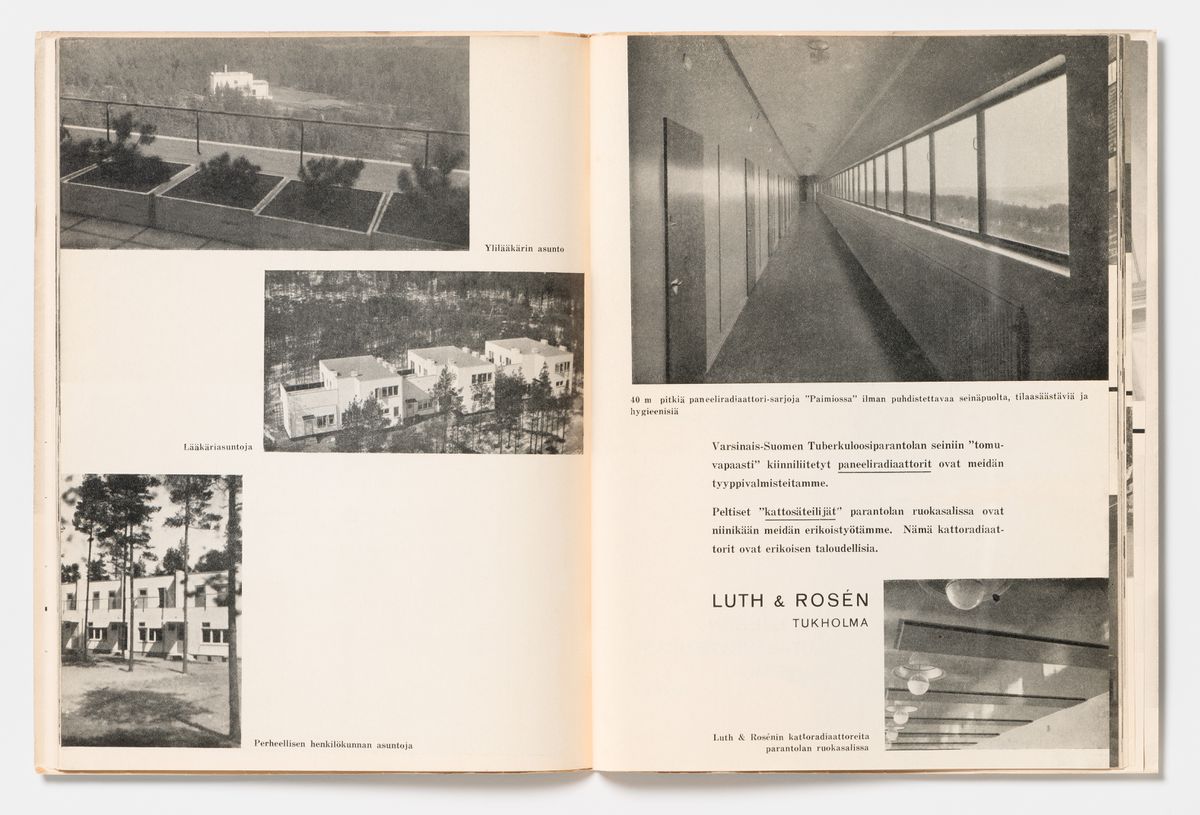

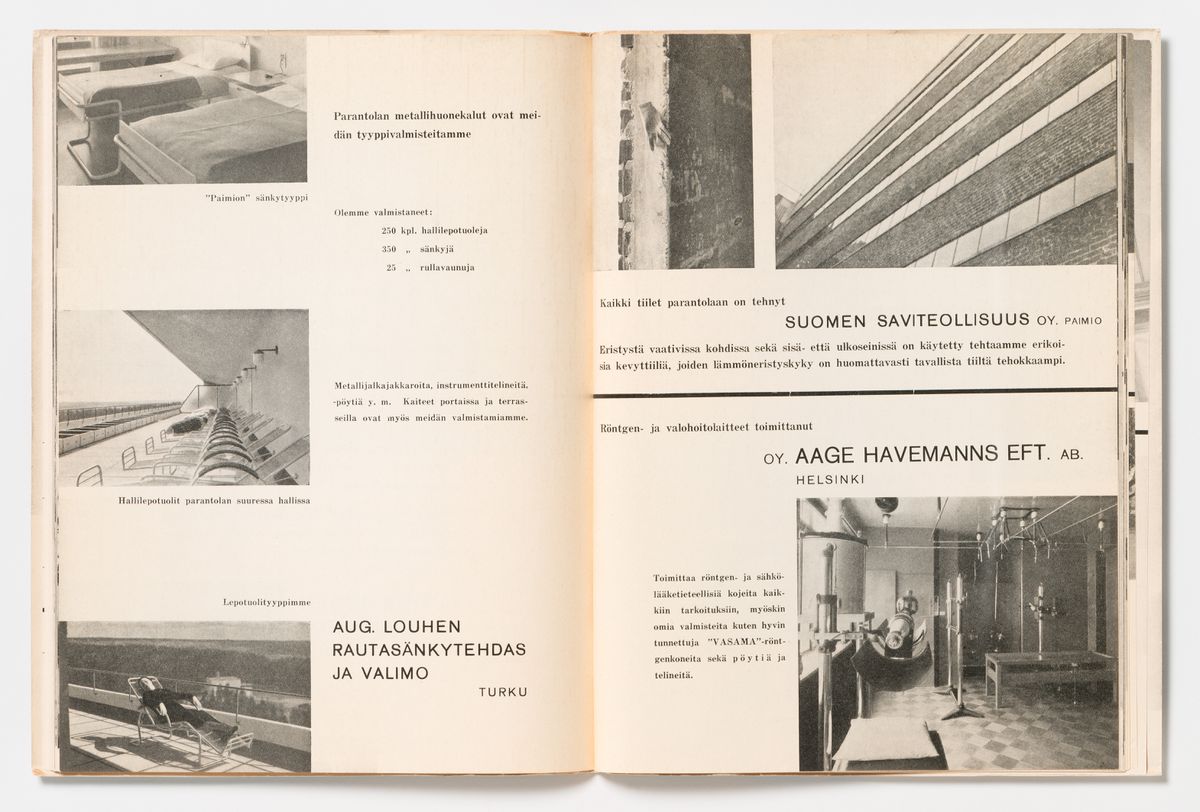

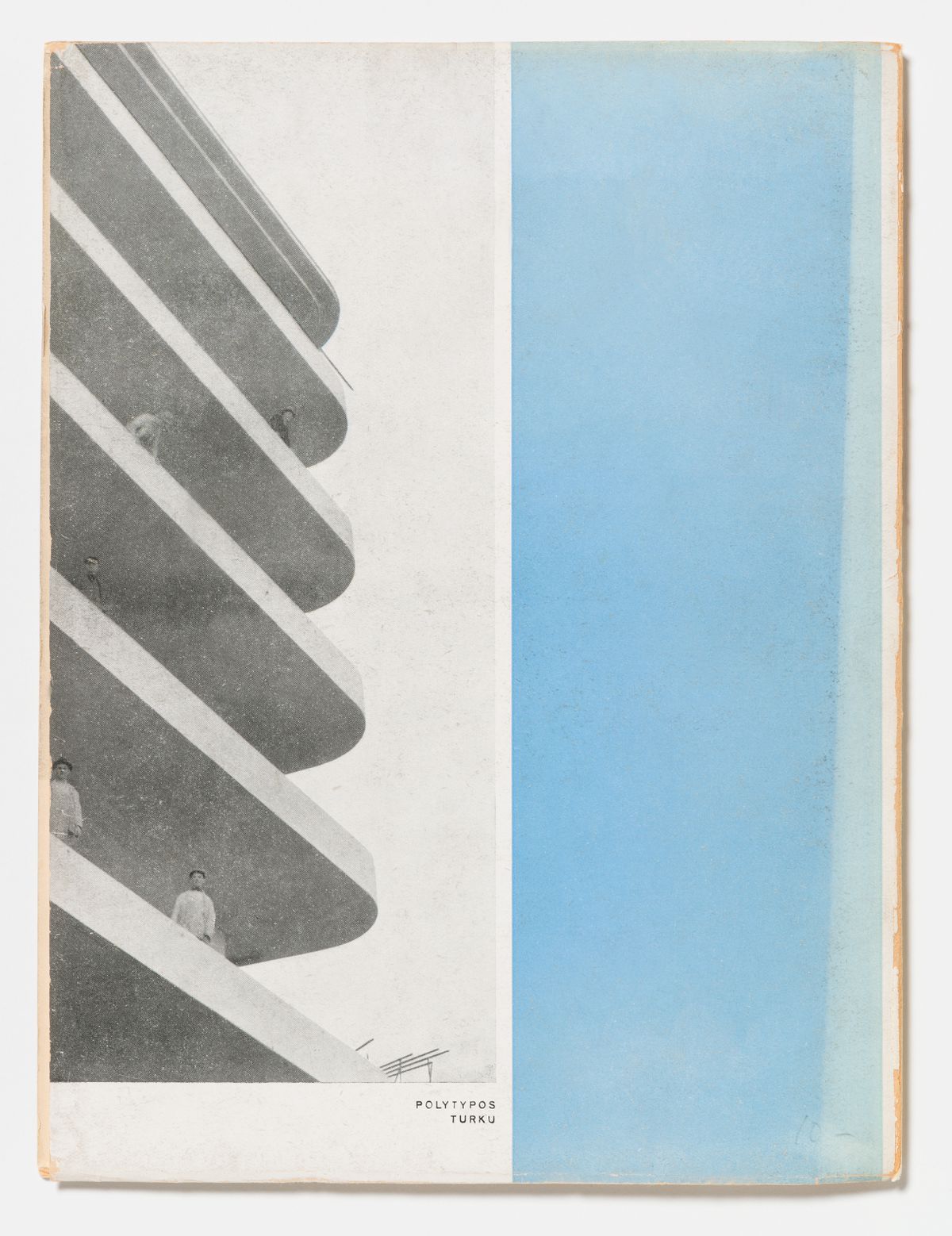

Inaugurated in 1933, Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Tuberculosis Sanatorium would become one of the icons of modernism and feature in countless histories of modern architecture. A key to the fame of the project that illuminates the strategic role Aalto himself played in its creation is preserved at the CCA, in the form of a light-blue paperbound and rather peculiar little book, Varsinais-Suomen Tuberkuloosiparantola, one of the earliest publications on Paimio. Although written entirely in Finnish, a wealth of images—two-thirds of the seventy-five pages are illustrated—document the construction of Paimio, reproducing plans and photographs of various building stages, and plainly advertising the building industries supplying firms and craftsmen involved in the project. This renders the book accessible and entertaining to non-readers of Finnish as well.

The editorship of the book was shared by the secretary of the building committee, representing the Finnish state, the founder of the sanatorium; Paimio’s senior physician; and Alvar Aalto. This collaboration reflects the joint endeavour between socio-politics, medical expertise, and architecture that led to the realization of Paimio. But while introductory articles justify the project by providing a historical overview of lung diseases in southern Finland and indicating the socio-political relevance of the disease, Aalto’s article redirects the reader to the actual protagonist of the publication: Paimio’s architecture.

Read more

The tuberculosis sanatorium was one of a number of “new” institutions to emerge in the nineteenth century relating to the specialization of medical treatment, and although it aimed to be regarded as a scientifically founded medical institution and was clearly not a “hotel,” the mechanisms to recruit “guests” were similar. Since often a mix of “paying” and “non-paying” patients was admitted—or had to be attracted—advertisement became an important aspect in the operation of this modern institution.

But unlike earlier sanatorium brochures (examples of which are found at the CCA),1 the marketing strategy for Paimio was not directed to the potential client but was meant to attract a much wider public, including architects and planners in Finland and abroad. Instead of showing diagrams and photographs of fairly bizarre medical instruments, or of patients sunbathing or receiving medical applications that evoke T. C. Boyle’s thoroughly researched The Road to Wellville (1993), the Paimio booklet fails to depict any patients at all. The booklet does not advertise a relaxing atmosphere, nor does it promote the advanced medical treatment provided; instead the publication is dedicated to the building itself—its planning, construction, equipment, and interior fittings.

Aalto provides equally detailed information on structural solutions, insulation, steel-frame windows, and washbasins, and he supports every architectural detail with the respective supplier or construction firm, freely sharing experience and expertise, and indeed providing a construction manual for imitation. What for the majority of architects today must seem a hardly imaginable approach opened up the sanatorium’s potential as a projection surface for the local industry, and thus shows Aalto’s skill at providing a successful marketing strategy for his project.2

Aalto used the sanatorium’s potential as a showcase for socio-medical and economical endeavour by “selling” Paimio as a combined package, promoting his architectural design not only as especially modern and hygienic but also as a response to national demands of the time. The publication of Paimio became a major part of the project—if not a project in its own right that took a decisive step towards the creation of a modernist icon.

-

Compare with brochures on Sanatorium Trois Rivières (ID:87-B10106, ID:87-B10107), Galen Hall in Atlantic City (ID:87-B14915), and Grand View Sanatorium in Wernersville, Pennsylvania (ID:87-B9443). ↩

-

Given that Paimio was created in a national program during the (relatively mild) economic downturn in Finland in the early 1930s, this was an important way of securing local interest in the project. ↩

Eva Eylers was here in 2009 as a recipient of a Collection Research Grant.