A Tenant’s Paradise (Lost)

Matthias Sauerbruch interviewed by Albert Ferré, with a series of photographs by John Gossage

- AF

- How would you characterize housing in Berlin today? What is the current situation?

- MS

- Where to begin? It’s important to give some historical context. The very first projects in Berlin that one could describe as housing—as opposed to houses—were built in the early eighteenth century as accommodation for invalids. Soon afterward, there were barracks for soldiers, but also for the families of soldiers. The history of Berlin is closely tied to militarism. Berlin grew into a city through the expansion of Prussia, and Prussia expanded with aggressive military force. So Berlin had a large population of military personnel.

In the eighteenth century, houses were normally owned and occupied by extended families and their servants. If the owners were craftspeople, they also had their workshops and staff in the same building. If they were traders, their house included a store. But, in addition to that, as a citizen of Berlin, you were required to accommodate up to two soldiers and their families in your house. Only if you paid a certain amount of money were you freed from this duty. So barracks were needed to cope with a growing number of soldiers, and of course this helped with the control and organization of the military.

Mass housing came about with industrialization and the emergence of a massive industrial proletariat. Between the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, when the German Empire was founded, and the beginning of the Second World War, Berlin grew by something like a factor of six. There was an enormous demand for housing, and for the first twenty or thirty years of this period, this need was met through what became the pre-dominant Berlin typology: Mietskasernen, “rental barracks,” which were twenty-one metres high and arranged along streets and around courtyards. They were sometimes several layers deep in one block, lining the perimeters of their respective sites, party wall against party wall. - AF

- Was this done on virgin land?

- MS

- Yes, it was an explosion of the city. It was made possible through a municipal masterplan—a set of rules for land division—and there was also a strategy for infrastructure, to manage traffic, sewage, and things like that. But the city itself was built by private developers, and so it was exploding with real-estate speculation.

Read more

- AF

- So, from the nineteenth century onward, the majority of Berliners were tenants?

- MS

- The basic unit of the city was no longer the family house, but the apartment. Families rented from a landlord or were given space by the state or the military. And still today, 85 percent of all households in Berlin are occupied in tenancy; they are not owned. By contrast, in London you have maybe 20 percent rental accommodation.

By 1940, Berlin had about four and a half million inhabitants, on a footprint that was approximately half of what it is today. Berlin was also heavily industrialized from the nineteenth century on. There were many factories, and the city was a leader in the electric revolution. All of that fell away after the war because so much property was destroyed and because the city was divided into four sectors and then, de facto, into two sectors. The population of West Berlin shrank to about two million inhabitants. The city was in the middle of Soviet territory, which was the worst possible location to start or continue a business. So the companies that were still existent in Berlin moved their assets, their people, and their production into West Germany, but of course they had to leave their buildings behind. West Berlin was depleted of industry, and in the East the Russians took many industrial installations apart and moved them further east, out of Germany. So the situation was similar on both sides of the wall, in that sense.

As a consequence, an enormous amount of buildings were empty after the Second World War. In the 1980s, as students, a friend and I lived in a three-room apartment that was one hundred square metres in size, and we paid something like three hundred marks—about one hundred and fifty euros—per month in rent. The housing stock was relatively good but the rent was incredibly cheap. Obviously there was degradation, and the technical and sanitary standards were low—my very first apartment in Berlin had a toilet out in the staircase. For heating, you had to bring coal up from the basement and fire it in the oven every morning. But if you’re a student, you don’t particularly mind these kinds of things.

Once the German army was re-established in 1955, it came with compulsory service for men. You either had to do military service, or work in a hospital or do some other civil service. However, if you lived in Berlin, because of the status given to the city by the Four Power Agreement, you were exempt from this service. Many young men came to Berlin; there was a crowd of non-conformist people settling in the ruins of the metropolis, which in many ways offered very favourable living conditions. This was a reversal of the eighteenth-century situation; this time, the city didn’t grow because of soldiers but because of those who were avoiding military service. - AF

- But you’ve skipped the Weimar period.

- MS

- Right. After the trauma of the First World War and the end of the monarchy, Berlin was run by social democrats, for whom social housing was a very important issue. From the 1910s until the 1930s, housing associations and co-operatives in different forms arose. There were many efforts to reform housing and to offer better living conditions. The famous Siedlungen, the housing estates, were built at this time. The Siedlungen were founded on the outskirts of the city because the land was cheaper, and the location also corresponded with ideas of fresh air and healthy living in nature, where children are able to play outside. It was a reaction against the overcrowded and unhealthy conditions in the very tight courtyards of the typical city blocks—there were serious hygienic problems in the courtyards; tuberculosis and even typhoid fever were not uncommon. The alternative cooperatives that started the Siedlungen grew into large housing associations in Berlin. GSW, for example, whose headquarters we designed in Berlin in the 1990s, was one such association. During the Weimar years, they had been clients to Scharoun, Mies van der Rohe, Häring, Taut, Forbát, and others. When we met them in the early 1990s, they owned seventy thousand apartments in West Berlin. After the wall came down, they inherited eighteen thousand more from the former East.

In West Berlin, these housing associations were almost the only clients left for architects. The real-estate market was non-existent until the reunification, because demand and thus rents were so low that you couldn’t make much money without subsidies. Families who still owned houses couldn’t afford to maintain them. There was no investment, sometimes not even in basic repairs. For example, many of the plaster mouldings on facades that had come loose during the bombardments were not repaired, but just knocked off. Today you see many buildings that, in the nineteenth century, had historicist decorations on the facades and that are now totally plain. There was no real-estate speculation like you would get in London or Paris. Berlin was a tenant’s paradise. Its population grew very slowly, but it never returned to the four and a half million that it had been before the war.

Quantitatively speaking, there was no need for new housing, but there were large programs of Sanierung, efforts to raise the standards and quality of the housing stock. In both East and West, because of heavy war damage, hygiene problems in the former Mietskasernen, modernist ideology, the need to create employment, and the political desire for a new beginning, Sanierung more often than not meant the demolition of entire quarters in order to replace old stock with new buildings. In the East, this was carried out very thoroughly, because there was no democratic decision making to slow the process down. But it happened less extensively in central areas of the East, and rather in the suburbs where new towns, now much denser than the original Siedlungen, sprang up. Wherever historic buildings were left alone, they were decaying. Around 1990, in both the East and the West, there were still entire neighbourhoods where little or no maintenance or repair had been done since the war; you could see the bullet holes in the facades. In West Berlin, in the 1970s, people started to oppose demolition because the old apartments were actually better than what was being built. Empty buildings were occupied by squats and many were repaired by the tenants only haphazardly. Strangely, it took the squatter movement to produce an understanding of the quality of the existing buildings. The policy of replacement slowly changed into one of repair. In 1984, half of the Internationale Bauausstellung (IBA) was about repairing the city in the sense of literally repairing buildings and neighbourhoods, and the other half was about repairing the city in the sense of the typological reconstruction of the traditional European city, to suggest continuity where there had actually been violent rupture.

- AF

- So when IBA took place, it wasn’t a response to a big need for new housing?

- MS

- Not at all. The city housing associations had been drafted to build the IBA buildings. All of the newly built IBA projects—or almost all of them—were done with public money in one way or another, and because there were certain standards that had to be applied to the apartments, they are very similar; it is really only in the facades that they differ. This is somewhat consistent with this idea of reconstruction of the city—very different from the IBA ’57, in Hansaviertel. This earlier exhibition was all about a new beginning. It took place in an area that was very badly damaged, but that could have been repaired. Instead, the remains of historic buildings were removed, the streets were re-routed, and a totally new urban pattern based on the CIAM city was established. And the architects experimented with new formats of living—not just in urban terms but also in terms of the individual apartment. But, on a very modest level, that fit the post-war economic situation.

Anyway, all of these post-war housing activities happened in a relatively relaxed environment, economically speaking; almost all of these projects were directly or indirectly subsidized by the central government. By the 1990s, the city had amassed five hundred thousand social housing apartments in all, which was quite a lot for a population of less than three million. After the reunification, when Berlin had to find ways to become financially independent again, the government—a coalition between the Social Democratic Party and the Left Party (Die Linke)—decided, among other things, to sell off apartments. Klaus Wowereit was the mayor; “Sparen, bis es quietscht” was his motto. Save money until it hurts. - AF

- Socialists throughout Europe did this during those years.

- MS

- GSW’s assets were sold. In fact, the whole company was sold. Their apartments were sold at an average rate of forty thousand euros apiece—nothing. It was unbelievable.

- AF

- So all the public housing—all the housing that was managed by public housing associations—became private.

- MS

- Well, just under half of it. Apartments were mostly sold to equity firms or other kinds of investors, who would renovate and re-sell them. The investors upgraded the apartments so that they would come out of the low-rent sector. They were allowed to do this because the subsidy rules only required you to keep the rents low for ten years. After that, you could do whatever you liked. They made enormous amounts of money, of course. Commercial companies like Deutsche Annington have replaced the state associations as landlords. All of this happened based on the assumption of a shrinking city. But, around 2007, the city started to grow again.

- AF

- Suddenly there weren’t enough apartments.

- MS

- Over the past few years, the city has been growing by more than thirty thousand people per year. In 2015, eighty thousand refugees were accepted into Berlin on top of that. And the amount of space that an average person inhabits has grown from about twenty-five square metres just after the war to about fifty square metres today.

- AF

- So there’s a problem.

- MS

- Exactly. There is an obvious problem in terms of numbers, but there is also a problem of failed responsibility. A large part of the population rent apartments and expect to keep on renting at low prices, but the market prices have been rising quite dramatically. The social rent in Berlin is fixed at six euros and fifty cents per square metre, per month. If you make a fair calculation, at this moment in time, for an investment that would achieve a reasonable rate of return similar to other investments, you need a rent of approximately ten euros per square metre, per month, even if you’re building only a modest house—that meets German standards—on land at an average price. So there’s a gap of about three euros and fifty cents, and that needs to be subsidized by the government. Obviously, the whole policy backfired. The financial problems have been solved only in the very short term; the debt will hit future generations, and this policy perpetuated the expectation that, as a citizen, you have a right to an apartment that is comfortable in terms of size and standards, and that you have to pay only six euros and fifty cents per square metre for it.

- AF

- But surely your means are tested, to see if you qualify.

- MS

- Yes, of course, but in Berlin, more than 50 percent of the population don’t pay taxes, because there are so many students, retired people, and people on welfare. That’s a huge problem, and the government is trying to make popular decisions in order to secure their votes. Die Linke is now arguing for a kind of state-managed housing system, like what existed in the GDR or in Britain immediately after the war, with Clement Attlee’s Labour government. This will lead to further debt that won’t be manageable. In any case, the system seems only vaguely tenable at the moment because the interest rates are being kept artificially low by the European Central Bank. The whole thing will collapse sooner or later.

- AF

- The government is subsidizing the apartments, which means that it’s paying the companies that own the apartments.

- MS

- Right. But developers obviously prefer to make upmarket housing because that’s the easiest way to make a good profit. But there is now a rule in Berlin according to which you have to provide 30 percent of any housing project at affordable rates. Naturally, developers don’t pay this out of their own pockets, but transfer the difference to the other 70 percent. So if you’re a local and you are buying an apartment in Berlin, you have to not only pay the state subsidies with your tax, but also help finance the affordable apartments of your immediate neighbours. This makes it hard to own and it creates a lot of conflict.

- AF

- So if interest rates went up, the system would collapse.

- MS

- Yeah. In any case, all the European states have so much debt; the whole situation is volatile. In Germany, people have very high expectations for the technical standard and the amenities in their accommodations, in terms of thermal performance and sound attenuation, for example. In some cities—although not in Berlin anymore—you have to provide car parks for every apartment. There are certain ratios of playgrounds and green space, and many developments have to finance schools and kindergartens. All this keeps the price up. Similarly, sustainable measures you think you ought to have—like geothermal heat pumps—also cost money and are added to the rent. So the high technical expectations go along with an ever-diminishing architectural and material standard.

- AF

- How do architects react to this?

- MS

- Our office is only now doing serious work with commercial housing developers on a larger scale; we have just started to get acquainted with the situation. For example, we designed the masterplan for twenty-one buildings across the street from our office. It’s interesting to see the building site every day and to see how efficiently it is being managed. The whole package was contracted to one company, and they are organizing the work like a production line. That seems positive, but of course the developers are still cost engineering everything else, which we don’t like. For example, the facade systems are now typically reduced to plaster finishes on top of polyurethane foam boards that insulate concrete block structures. Plastics are used everywhere, even in windows, which are pretty ugly and not very sustainable. Lowering the investment cost is about the only thing plastic windows are pretty good at.

- AF

- But is this lowering of standards a result of the idea that the buildings should not last—that they’re not built to last the way they used to be?

- MS

- That’s an interesting question. Of course the developer pretends that these houses are built to last forever, because that’s part of the marketing line. In reality, that’s not the case. Certainly the facades and interior finishes are not built to last forever; they will probably have to be replaced in ten or fifteen years. But on the other hand, traditionally, houses always need repair.

- AF

- Right.

- MS

- They need to be maintained. This expectation of wanting to build something that will never have to be touched again is a new phenomenon. If you live in a London terrace, for example, you become very quickly attuned to the fact that every three to five years you have to repair the roof because it’s leaking. Some colleagues, like Arno Brandlhuber, for example, develop creative approaches to lowering standards; he interprets building rules quite freely and is not afraid of solutions that are less lasting. For example, for his own house in Brunnenstraße, he made a facade out of extruded polycarbonate panels. It’s a very cheap facade, but it’s not very good in terms of performance. This kind of approach works for clients and users who really buy into the idea, but on the normal housing market a building like this would be considered sub-standard. On the other hand, Arno’s project is very honest about the situation. It is openly showing what everybody else is getting too, except that, on the market, the building would be wrapped in a facade that is designed to say, “I am durable; I am good architecture.” His project is brutal on a material level, but spatially it is actually quite generous. Arno was lucky to find a very central site with a half-finished building—a project that was in insolvency. The basement and some walls were already there. He just completed what he found, so the cost of land—which is also a critical factor—was low in this case.

In our office, we have been exploring different approaches. For example, in Hamburg, we’re just completing a modular housing project that is prefabricated. The modules are made in Austria; they make complete apartments.

- AF

- And it’s wood construction?

- MS

- It’s all wood, yes, with a concrete table and concrete cores for circulation and services, and then these prefabricated elements.

- AF

- Is it subsidized housing?

- MS

- No, it’s private. It’s market driven. The rent per square metre does not meet the social housing level, but the overall amount is still affordable, since the apartments are so small; actually they are quite efficient and comfortable. In terms of ecology, this is a real answer. The small units are light in terms of the carbon-dioxide footprint and, obviously, wood is a carbon-negative material, with the modular prefabrication reducing energy input in production. You have very little waste. You have to transport from the factory to the site, but only once. Since you don’t have the usual complications of a building site, the production phase is fast and less disruptive for the neighbourhood. In terms of quality, it’s like it was made by a joiner in a workshop. The concrete part is basic, but the timber work is excellent. It’s a re-incarnation of the old idea of an industrialized building, and everything has to fit onto a truck. The unit is approximately container sized—of course you can join the units together, but everything is based on this constraint. It’s a sort of tatami structure, and everything has to fit under the motorway bridges. It is currently probably slightly more expensive to build, but this is a prototype project, so the price might come down in the future.

- AF

- If you produce more units?

- MS

- If there is more experience and more competition, because at the moment there are only a handful of companies that can do this. A couple of valleys in Austria have a few families that specialize in this, and they’ve really got the market. In Germany, the challenge up until very recently has been fire regulations. They vary from state to state, but most didn’t really allow you to use timber. Our project is a seven-storey building and, strictly speaking, timber was only allowed up to two and a half storeys. In Hamburg, our project initiated a change of fire regulations, and now you can build up to twenty-four metres in height if you provide compensatory measures. In our case those are the concrete cores, so that you can always escape into a safe staircase if there’s a fire. The facades are divided by horizontal ledges, to make sure that the fire that would not come up the facade and so easily leap from floor to floor. Once these strategies become more mainstream, maybe the price will come down. I think it’s an interesting future for housing. We currently need a lot of housing for refugees, and the authorities are just making container cities; people are being put up with little dignity and no long-term perspective for the city. Here in Berlin, the government is building so-called Tempohomes made of steel containers, like the accommodation that we sometimes have for workers on building sites. Everything is covered in plastic and it’s really basic; it’s fine for a few months or so, but it’s not suitable for any longer period. It’s really a missed opportunity, not to design something better—quite sad. The hope was that we could learn from the simplicity that is needed and that this would help us break the clichés of the typical family apartment, for market housing to get away from the pattern of the nuclear family: mother, father, and two children. That is not the norm anymore. 50 percent of the population live alone, and of the households of more than one person, only 30 percent are actually in that nuclear format.

- AF

- Right. You have all this old housing stock conceived for another type of social set-up. But the nineteenth-century apartment is very flexible, in the sense that all the rooms are more or less the same size.

- MS

- But the flexibility is really a result of the generous size of these apartments: rooms are much larger than in contemporary buildings, floor heights are greater, and apartment sizes are much larger, as accommodation for household staff was not uncommon in bourgeois circles. In the nineteenth century, these apartments might have been occupied by large families and so would have been relatively crowded, but, at today’s occupation rate, they offer a loose fit—very much contradicting the paradigm of efficiency. For example, in the old Mietskasernen apartments, there is almost always a room called the Berliner Zimmer, which is a direct result of nineteenth-century urbanization in Berlin. It’s the corner room of the internal courtyard. If you go around the courtyard, you always get four corners which don’t have a window, basically.

- AF

- Right.

- MS

- Or there is only a bit of a window for a very large room. On one hand, these rooms cannot be properly used, but on the other hand, everyone is invited to invent his or her own use for this room. It’s a luxury that comes cheaply, as you can’t really ask for full rent.

- AF

- So what is the way forward?

- MS

- One way out of Berlin’s housing dilemma would be if people decided to buy their apartments. For example, the government of Singapore is selling apartments at a preferred price to people in need—a subsidy, basically—and you buy with a government mortgage if you are eligible, if you have a certain income level. And then you can sell the apartment again after a certain period. They go back on the market, and you can basically make a little bit of money by selling it, even though it’s still restricted because it falls under this social housing rule. The chance of re-selling means that owners look after their apartments; they are generally kept very well. It’s a way for the government to support individuals and families directly. I think that’s a very clever way of doing it. In Berlin, continuous tenancy locks people and the government into a mechanism that requires an enormous amount of administration and carries this top-down mentality.

When Margaret Thatcher dissolved council housing in Britain and lowered the interest rates for people who wanted to buy—you almost need to have something like that. It has to be handled more responsibly than it was handled then, but I think something like that would really introduce some long-term change. - AF

- I’m curious about these housing co-operative projects. It’s a new phenomenon. Before, someone owned a piece of land and developed it. Now you decide whom you want to live with, where you want to live, and how you want to live.

- MS

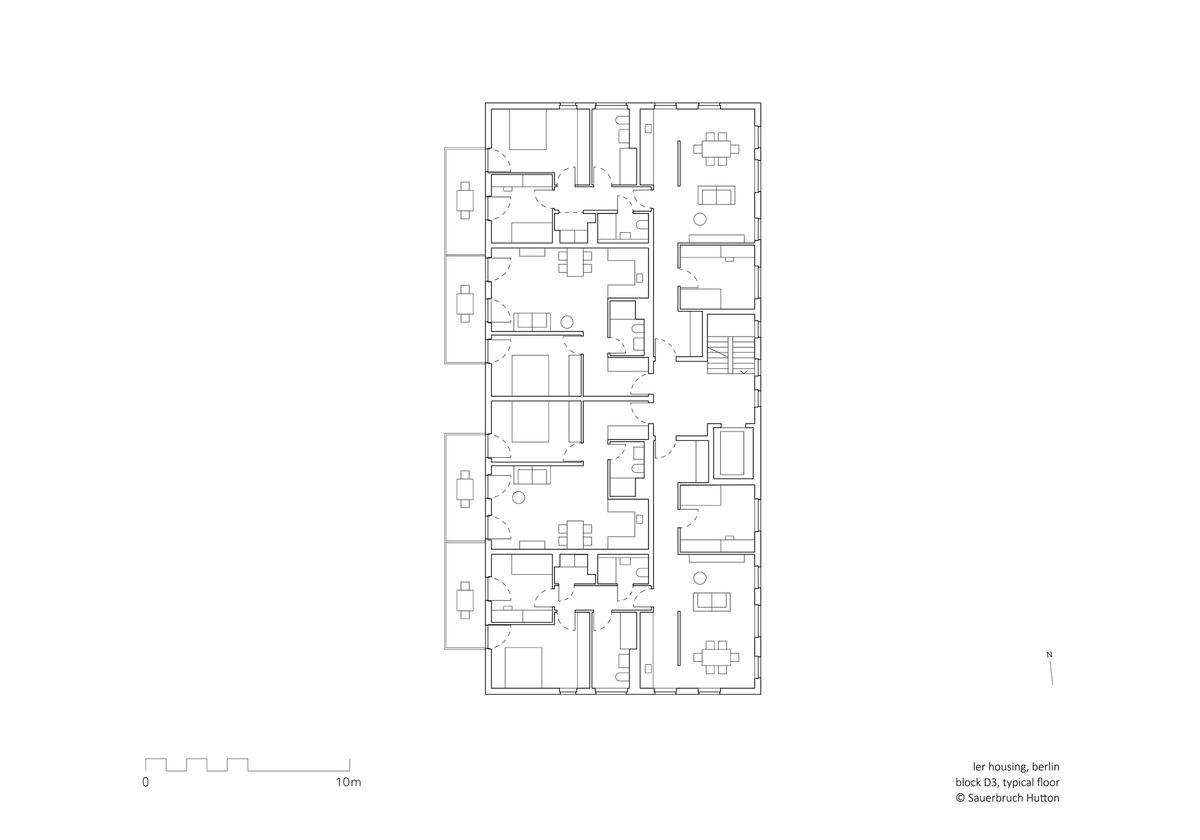

- Yes, we call them Baugruppen. In a project like our Haus 6, we designed a simple system-built structure that allows you to customize the plan, both in terms of basic subdivision of one floor into several units and in terms of the layout of each individual flat. You can provide for traditional families, partners, people who work at home, people who go out to work, grandmothers, independent kids, and so on. With a traditional apartment, you can’t do that. The user has to adapt to the product, and not vice versa. In addition, Baugruppen cut out the developer’s profit, if the clients commission architects directly, and if as a group they can afford a whole house together. It’s very good for the client, but obviously more work—albeit work that is more interesting—for the architect, because you are designing many custom-tailored flats instead of a standard layout that repeats on every floor. However, sometimes you are also running an adult-education class in architecture and building, and sometimes a psychotherapy clinic.

In commercial projects, this flexibility obviously doesn’t exist. We did try in one of the projects we are working on; we fought very hard to design the structure in such a way that there’s at least the possibility of removing two walls so you can make a more open plan. But this took a lot of energy. In general, you’re endlessly debating small details like the depth of the balcony, whether the kitchen is part of the living room or not, and so on. But you are fighting a losing battle, because the starting point of these projects is already wrong.

- AF

- And were these discussions on different configurations and the possibility of transforming spaces present in the IBA, in the 1980s? Not at all, right? It was really a very standard type that they were proposing.

- MS

- The discussions were probably similar then. Architects had far-reaching ambitions, but they were made to adhere to the standard configurations. In the IBA of 1957, it was different. If you look at the plans by Van den Broek and Bakema or other residential high-rises, there are some advanced examples. Luciano Baldessari made a tower with natural cross-ventilation. It’s basically an oblong rhomboid, and there are two convection shafts that run through the plan so you can cross-ventilate all four apartments in all four directions—it’s very unusual.

Van den Broek and Bakema have shared balconies. Or there’s Gustav Hassenpflug’s high-rise, which is all system built. It’s made entirely of prefabricated elements and it has double-storey balconies. Many of the ideas we are pursuing today in housing were in existence at that time. And the architects were experimenting with the minimal standards of the time—sometimes only at a height of 2.1 metres in the apartments. The so-called Swedish house—which was designed by two Swedish architects, Fritz Jaenecke and Sten Samuelson—has kitchens that are absolutely minimal. There was quite a bit of experimentation on the scale of the apartment at that time, but the IBA in the 1980s was geared toward the continuity of the city—Aldo Rossi, basically. - AF

- Could you identify a cause or a point of origin for the desire to live together and to take that to the design phase, as we see in the Baugruppen?

- MS

- Well, I think it’s an indirect result of the liberation of individual lives. Women’s rights, gay rights, and social equality—all of these things that we would consider achievements—certainly mean a greater degree of freedom for many people. But they also result in the fragmentation of the traditional formats of the social structure and lead to greater individualization. In the eighteenth century, the house was the unit of the city. It contained the family that owned it, the household staff, and employees if the family made or sold goods. In the nineteenth century, the apartment was the unit. Now it is really the individual that has become the basic element. Berlin is a city of singles.

There are some pioneer housing co-operatives that respond to this condition quite well, such as Spreefeld, a project in Kreuzberg, by the river. It’s like a village and it offers a variety of flats, including shared apartments. It also has three relatively large common rooms, various communal terraces, and a boathouse with a boat for everybody to use. Holzmarkt, another project, on the other side of the Spree, is under construction at the moment. It will have a club, a hotel, a restaurant, and various workshops. I think it’s a really interesting project, although architecturally speaking it is maybe a little questionable; it’s made to look bottom-up, when in reality it is quite controlled.

With this condition of the city of singles, I think it’s important to create spaces around the house that are inviting for inhabitation—to sit around and chat, to meet people. Years ago, we did a project in Helsinki. It’s being completed now, but unfortunately not quite in the way we had anticipated. It’s a masterplan for a block in Jätkäsaari, a former harbour area that is under redevelopment. It was a competition called Low2No, and it was meant to be a nearly carbon-free neighbourhood. We designed spaces for neighbourhood activities, shared childcare facilities, small-scale businesses, and a common sauna—which is very important in Finland. But all of this was wiped out during the implementation. It’s a conundrum; if the state supports everything, and everyone ends up being dependent on the state, this leads to obvious problems. But if you leave the problem to private development, the market rules everything. And if the expectations of return are short term you won’t be able to implement the necessary foresight and care, not to mention any untested ideas. In Helsinki, the whole thing was initially driven by Sitra, a government agency for innovation, but after a change of policy they withdrew their support, and so all the wonderful community facilities were ruthlessly eradicated by a commercial process that—ironically—was driven both by the exorbitant land prices the city was asking and the cost of the competition itself. - AF

- It sounds like you need either a set of clients who have the resources and vision to make this kind of co-operative housing possible, or a very strong state that will make it possible to implement. This can’t be left to developers.

- MS

- I think people should take their fate into their own hands and get involved, instead of continuously complaining that the state is not offering them enough. And that can only happen through ownership. Baugruppen are a good initiative, but it’s difficult for people with more limited means, because there comes the moment when you have to deal with your bank. Baugruppen are supported by very few banks, and you have to be able to offer collateral. It might be easier to become a member of a co-operative; you have to pay a fee to get into it, but then you just pay a monthly sum, like rent. You are an owner, the apartment is your collateral, and the financial weight is spread in quite a reasonable way. Of course, this kind of shift in the housing landscape won’t happen overnight; we need a little bit of a revolution in Berlin.

Matthias Sauerbruch is an architect and founding partner in the Berlin-based practice Sauerbruch Hutton.