Living in Polychrome

Text by Nicola Pezolet

Colour is vital. It is one of life’s indispensable raw materials, like water and fire. Human existence without a colourful environment is inconceivable.

—Fernand Léger, La couleur dans le monde, 1938

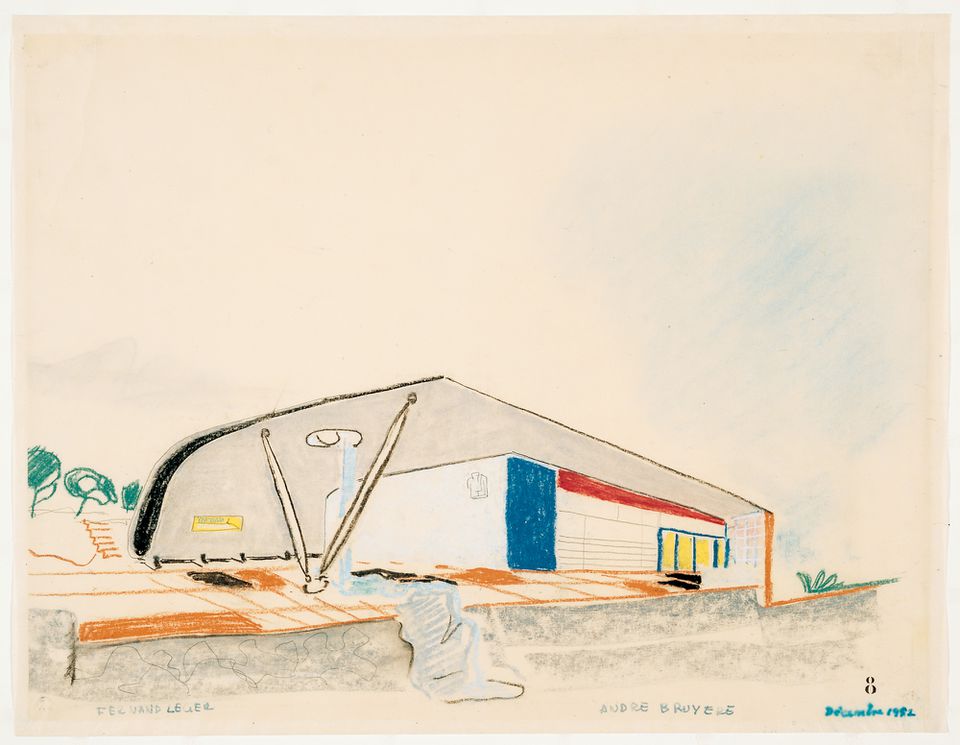

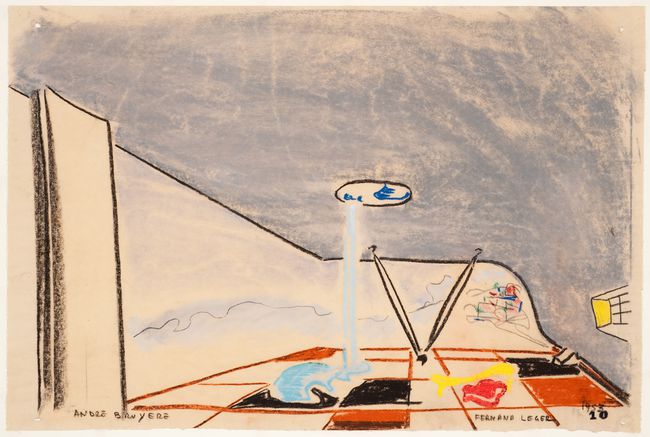

The Village Polychrome is a series of drawings in the CCA Collection by the architect André Bruyère that shows different aspects of a prospective settlement near Biot, a small village overlooking the Mediterranean in the southeast of France. The visual artist Fernand Léger was responsible for the bold colour scheme for this suburban development, which rejected the austere boxiness of postwar functionalism in favour of more playful lines and asymmetrical shapes. The patron of the project was Francisco de Assis Chateaubriand Bandeira de Melo (a controversial media mogul, diplomat, and art collector from Brazil) who hoped to create a small village for a community of two hundred Brazilian students in France. This project is indicative of the transnational exchanges that occurred between the French and South American art worlds in the first half of the 1950s. At the exact same time, Léger, along with André Bloc, Victor Vasarely, and others, was commissioned to paint several polychrome murals for the buildings by Raúl Villanueva on the University of Caracas campus in Venezuela.

Although Léger and Bruyère are from different generations, the two men shared similar concerns about the necessity for modern architecture to act as a “synthesis of the arts.” Indeed, during the postwar Reconstruction, Léger and many other avant-garde artists who published in little magazines such as Art d’Aujourd’hui and Structure sought to undo the burden of Fascism by creating a new modern subject through the wide scale application of what was considered to be the joyous and redeeming language of polychromy. Chief among them was Léger’s close friend and former collaborator Le Corbusier, whose controversial Ronchamp chapel showed the architect’s renewed concern for the spiritually uplifting power of colour, as well as for structural expressionism and plasticity. While many elements of the Village Polychrome are certainly evocative of the biomorphic organicism of some of Le Corbusier’s late work, they also recall the experimental designs of younger mid-century architects such as Oscar Niemeyer, Eero Saarinen, and Paul Nelson.

According to a series of specifications, the total allotted budget to the Village Polychrome was the onerous sum of 236,000,000 Francs. The money was designated for the purchase of a large plot of land (40 hectares), the construction of roads and other infrastructures such as parking spaces, green spaces, a restaurant, a museum, a public sculpture, a movie theatre, and most importantly, student housing facilities and ten fully furnished villas. Bruyère devoted most of his attention to a specific villa that was supposed to be inhabited by the patron’s visitors. Several sketches, subsequently coloured with bright pastel crayons by Léger, show it from different points of view. Since the Village Polychrome was thought of as a total work of art, the artists consistently blur the line between inside and outside by coordinating the furniture and the architecture of the villa to its general surroundings. For instance, the small chair and table, made of curvilinear, sinuous shapes, are evocative of natural formations, as are many of the other public buildings nearby. Also, Léger and Bruyère sought to create a relaxed proximity between the users and the rural setting. Glass windows, surrounded by brightly coloured horizontal panels, are carefully disposed around the building, offering different vistas of the surrounding landscape. The most interesting architectural element is the large roof (made of what appears to be reinforced concrete) supported by a pair of V-shaped metal rods that extends on the outside of the house to create a small patio space. The architect’s desire to blur the boundary between inside and outside is suggested here by his decision to pierce a round opening through the roof, thus creating an impressive auditory and visual spectacle for the visitors sitting outside, as water ripples through the ceiling to create a small pond below.

In the end, the patron failed to fund the project, therefore confining the Village Polychrome to only twelve sheets of paper. But even if the project never materialized and did not receive any press coverage, these drawings are still very precious and timely documents, and vividly illustrate the utopianism of the postwar discourse on the “synthesis of the arts.”

Nicola Pezolet was a Collection Research Grant recipient here in 2009, which is also when he contributed this text to our website.