Short Reckonings Make False Friends

Text and GIF by Alice Haddad

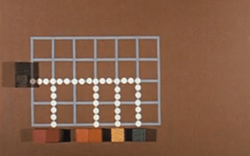

In Industrial Architecture: Ábalos&Herreros selected by OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen, the curators presented a series of printed CAD drawings from the digital archive of Ábalos&Herreros. Distinct from the exhibition, the selection of drawings here is a singular composition in the form of an animated GIF. Only the plans are presented, leaving out elevations and sections, and multiple views of the same project have been separated so that one plan appears at a time. The plans are reframed, regrouped, and rescaled: each plan takes the contours of the preceding drawing as a reference, and the ensemble is set in motion.

These simple manipulations and careful montage into a series of single frames were possible through software programs that operate on the drawings’ source material, that is, the original digital CAD files, which the Canadian Centre for Architecture acquired in 2012. The process of production of the GIF seems to mar the authenticity of the original object, which the archives relentlessly try to preserve. But, like the printed drawings in the exhibition, can the GIF pretend to provide the viewer with direct access to the original?

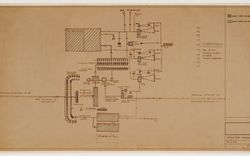

Some of the image files as we encounter them in Ábalos&Herreros’s digital archive were produced as early as twenty years ago, when computer-aided design first became an integral part of architectural practice. These files have been saved in their original state and the organization of the office’s project folders has been preserved, along with subfolders and other file types, sometimes carrying names that hint at the contents. Clicking on the files is usually the first, instinctive attempt to access the content, but it quickly becomes clear that, depending on the software installed on the computer being used, not all of the files will reveal their treasures instantly. Some will be corrupted, others will call for the installation of new software and still others will remain impossible to view as their configurations turn out to be obsolete or incompatible with the current operating system. Once the CAD file successfully opens through a compatible AutoCAD application, the delicate vector lines of the drawing, in their native environment, appear ready to be modified—they remain fixed only as long as none of the application’s many tools are utilized. The black, seemingly infinite space of the AutoCAD window works as the interface between the source code of the file and the computer screen’s pixelated surface. In this context, unless intentionally incorporated, the author of the drawing remains unknown. It is likewise unclear whether this particular view is the final version, what the author’s aims were in producing the drawing—digital study models, printed presentation panel views, or plotted construction documentation—and whether details such as scale, colour scheme, and line weights have been adjusted accordingly. As is the case with the design process, the experience of visualizing the original image file is also dependent on the software’s performance; it is necessarily shaped by the interface and the tools this interface provides.1 Consequently, the digital image is always a representation of the file’s invisible code.

Read more

In contrast to the traditional physical object, the digital image cannot be exhibited, only performed. The relationship between image and image file, rather than being that of copy and original, can be compared, according to Boris Groys, to that of music piece and score. Groys explains:

Each presentation of a digitalized image becomes a re-creation of the image. This shows again: There is no such thing as a copy. In the world of digitalized images, we are dealing only with originals—only with original presentations of the absent, invisible digital original. The exhibition makes copying reversible: It transforms a copy into an original. But this original remains partially invisible and non-identical.2

Performance always entails a certain amount of interpretation. The image acquires its character from both the interpreter’s appropriation and the changing context of display.

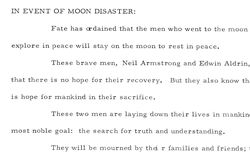

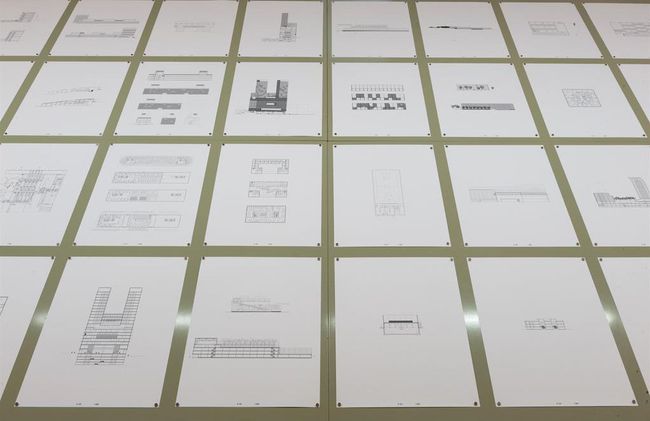

In Industrial Architecture, the drawings were printed on custom-scaled white paper laid out in a regular grid to fit the large surface of the exhibition tables. Their appearance was homogenized through the removal of residual information like text boxes and technical inscriptions, the overall adjustment of line weights, and the application of a monochrome black-and-white rendering. The systematic layout in chronological order and the minimal information on each sheet, consisting only of the project’s number and normalized scale, present the vast ensemble of drawings as a database, sketching a fictional analogy of their digital categorization. The viewer is invited to create connections across the table. The curators’ intention is to unveil the striking similarities between drawings from various projects over the years. Kersten Geers describes these projects as “false friends:” at first sight identical projects, which after a closer examination into their specific design and program reveal their differences.3

-

Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2001), 34. ↩

-

Boris Groys, Art Power (Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 2008), 91. ↩

-

Kersten Geers and David Van Severen, “Industrial Architecture seminar with OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen” (lecture, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, 11 March 2015). ↩

The false friends not only appear in the work of Ábalos&Herreros, but also reflect the friction between the CAD files and their printed version. The curators, in converting the digital image into a physical medium, increased the distance of the exhibited object from the original, and at the same time conferred new meaning onto it. The tension of this process is apparent in the paradoxical co-existence of the database and the narrative; the former being the objective collection structure of new media objects, while the latter is the main form of cultural expression of the modern age,1 a prime component of exhibitions and other discursive practices. Working with a digital database allows for infinite narratives to appropriate and structure the items it contains.

The GIF, in this instance, using the same source as the exhibition material, modifies the temporality of contemplation. It sets the pace, forcing the connections that the viewer was invited to make during a stroll through the gallery. With a different temporality, a different spatiality, and a different audience, it is a new work. Released from the atemporal confinement of the archive and now freely available on the Internet—though not free from copyright—the Ábalos&Herreros drawings lose their exclusive status. They are poor and vulnerable: they can be captured and transformed into another series of afterlives. In its defense, Hito Steyerl proposes that “the poor image is no longer about the real thing—the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence: about its swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities.”2

Alice Haddad was a 2014–2015 Curatorial Intern at the CCA. The exhibition Industrial Architecture: Ábalos&Herreros selected by OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen was held in 2015, and the book AP164: Ábalos&Herreros selected by Kersten Geers and David Van Severen, Juan José Castellón González, and Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu, with an interpretation in photographs by Stefano Graziani was published in 2016.