The Aesthetics of Engineering

Text by Katherine Romba

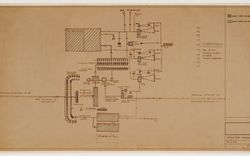

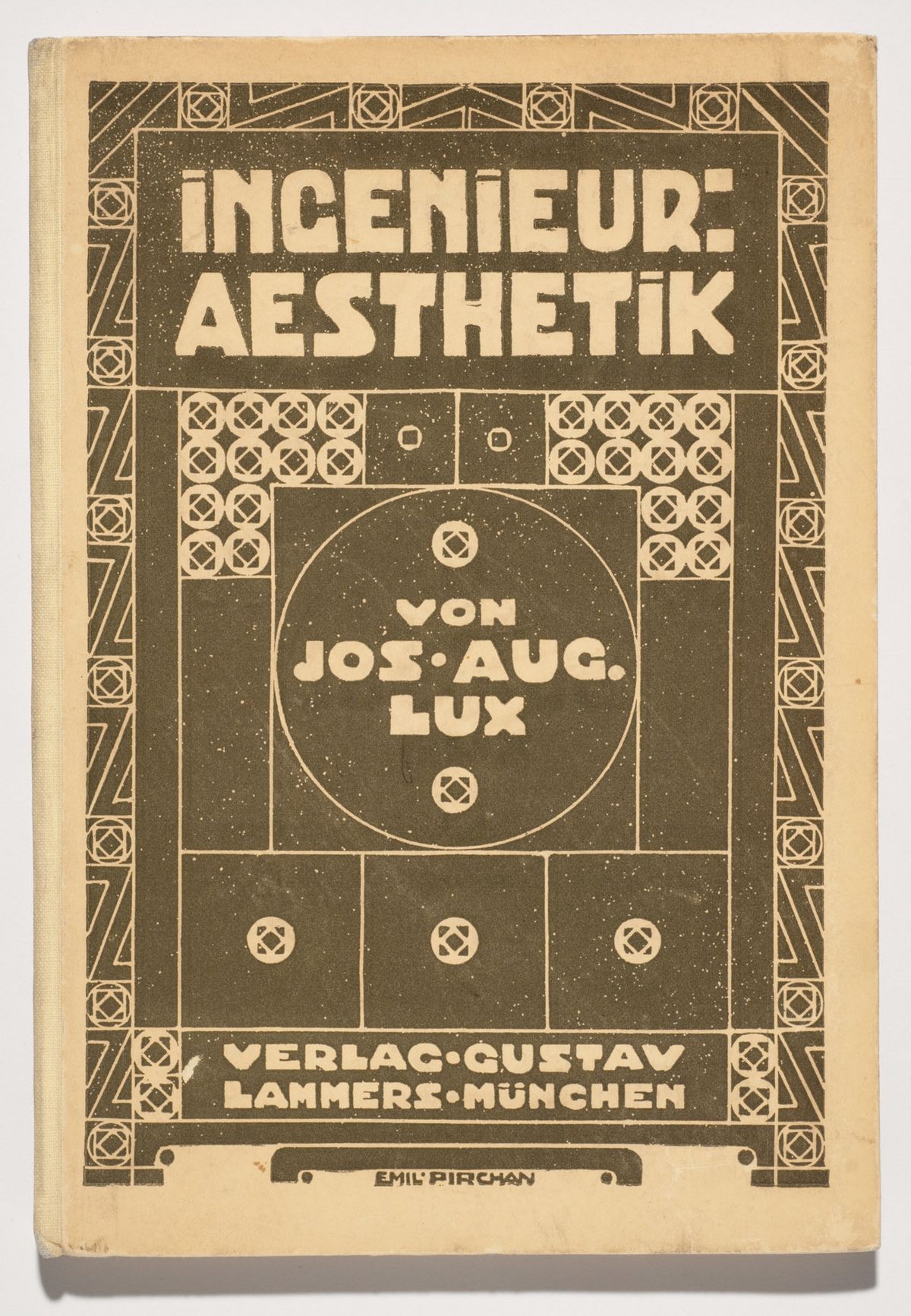

Ingenieur-Ästhetik (Engineer-Aesthetic) is a book about engineered structures and their beauty, which—the author Joseph August Lux (1871-1947) argues—stems from the fact that engineering follows the same principles that govern the design of the natural world. This book was written at a time when Germany’s industrialization had reached a level of sophistication and production comparable to that of Britain and France. Engineered structures and vehicles constructed of industrial materials and designed using new technology—bridges, towers, air ships, automobiles, trains—had indelibly altered the appearance and experience of Germany, prompting critics, like Lux, to speculate on their implications for society and culture.

Many critics contemporary with Lux judged the engineered constructions unfavorably. Recalling the criticism of Karl Marx, they judged modern engineering and the industry that made it possible to have a pernicious outcome for humanity. Factories were “dead” mechanisms to which the worker had become a living appendage. Like the British Arts and Crafts reformer William Morris, they claimed that objects and structures made possible by the machine lacked the marks of the handheld tool and thus lacked traces of the human spirit.

Other critics, including Lux, presented a more sanguine view of engineering and industry and their effects. While the opposing discourse had presented modern change as the tyranny of a new, lifeless culture, Lux and others portrayed change as having familiar and attractive natural traits. For Lux, engineering had enhanced and improved human capabilities; to take advantage of its possibilities, designers needed merely to grow accustomed to creating with industry’s “metallic arms.” (Also adopting this rhetoric of anthropomorphism, Deutscher Werkbund member Friedrich Naumann went so far as to portray industry as a diligent apprentice, claiming that early in its evolution, the machine, in order to improve itself, “had sat back behind the handworker and attentively watched him produce his art”1.

The focus of Ingenieur-Ästhetik, however, is not industrial manufacture but rather the engineered structures themselves. The principle guiding this book is that engineering operates much like an enhanced prosthetic limb, allowing us to extend our natural abilities. Hardly foreign objects hostile to humanity, engineering is “biological forms in construction”; iron constructions are “bundles of nerves through which flows a living energy”; and modern vehicles are agile “embodiments of our nervous system.” Like a number of other critics (such as Alfred Gotthold Meyer and Rudolf Metzger—both represented in the CCA collections), Lux rests his aesthetic argument on the principle that people find beautiful those forms with which they can “empathize,” concluding that in engineering’s animated vitality, “a new kind of beauty has developed.”

Katherine Romba consulted our copy of Ingenieur-Ästhetik as a 2009 Visiting Scholar.

Friedrich Naumann.“Die Kunst im Zeitalter der Maschine,” in Schweizerlische Bauzeitung (1904), 114