The Architecture of Photography in an Age of Obsolescence

Text and photographs by Robert Burley

In 1942, the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter coined the term creative destruction to describe the process of change that characterized our industrial-based economy in the twentieth century.1 Defined by modernity, this past century embraced new ideas and technologies while celebrating the disruption of the old. For Schumpeter, innovation creates obsolescence.

In today’s Information Age, innovation is a constant in our lives, to the point where radical new discoveries in technology have become part of our everyday. These innovations come to us in such great numbers and so quickly that it’s difficult for us to keep pace with the countless ways in which they affect us. However, this enormous wave of innovation has also created an age of obsolescence, one which has shaken the foundations of our society and culture. This is especially true in the worlds of physical media. Not just photographs but books, newspapers, music recordings—to name a few—are all being re-invented into new forms, and I believe we all share a common anxiety about staying current, so we are not left behind and we don’t become obsolete.

I saw in 2009 a restaging of the 1975 exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of the Man-Altered Landscape, shown at the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York. Although New Topographics received little critical attention when it first opened in 1975, it became one of the most written about exhibitions in the history of photography, second only to Edward Steichen’s The Family of Man (MoMA, 1955). New Topographics launched the careers of American photographers such as Stephen Shore, Robert Adams and Nicholas Nixon, and it was also one of the first exhibitions to include the work of German artists Bernd and Hilla Becher in the United States. Today, this influential show is seen as marking a turning point in the history of photography: one that signalled the radical shift away from the traditional depictions of landscape by photographers such as Ansel Adams and Edward Weston, toward un-romanticized views of stark, industrial landscapes, of suburban sprawls and of cities themselves. As stated by curator William Jenkins in his catalogue essay, these were photographs that employed “photography’s most important attribute: its ability to describe something accurately and in detail.”2

Read more

As a student, I remember these pictures as contemporary, cool and dispassionate; images of everyday things and places that maintained their status as documents while presenting a subtle and underlying existential crisis about our relationship to the landscape. Each artist worked at a small scale, and all but Stephen Shore worked exclusively in black and white. These pictures were unmistakably photographs. They could be nothing else, given the very nature of how they were made at that time. When I saw the exhibition again at Eastman House last year, I was suddenly aware of the media in a way that I had not been before. I can clearly remember thinking that what photographs used to look like in 1975 was certainly not what they look like now. And I found myself recalling a text by Rosalind Krauss:

Photography has then suddenly become one of those industrial discards, a newly established curio like the jukebox or the trolley car. But it is just at this point and in this very condition as outmoded that it seems to have entered into a new relation to aesthetic production. This time, however, photography functions against the grain of earlier destruction of the medium becoming—under precisely the guise of its own obsolescence—a means of what has to be called an act of reinventing the medium.3

The Information Age has rendered the concepts of medium and medium-specificity irrelevant: we have now entered a post-medium era.

While I didn’t view the 2009 restaging of New Topographics as an industrial discard, it was clear to me that these photographs—which were so much a part of my early years—had been re-defined through recent developments in both art and technology. They were unmistakably photographs, but from a previous era long past that, to my surprise, was my own. The small, detailed, mono-chromed images, created with silver salts and gelatine, had been redefined by digital media. Digital media, while forcing traditional photographic technologies towards obsolescence, has provided me with unprecedented control over not only the production of still images, but a range of media including moving pictures, sound, graphics and many applications related to the web. However, while offering a technological utopia, new media have also suddenly heightened my awareness of the old medium I’ve used throughout my career: film.

-

Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, socialism and democracy (New York: Harper Brothers, 1942). ↩

-

Robert Adams and William Jenkins, _New topographics: photographs of a man-altered landscape (Rochester, N.Y.: International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, 1975). ↩

-

Rosalind Krauss, “Reinventing the Medium,” Critical Inquiry 25, no. 2 (1999). ↩

-

Marshall McLuhan and Quantin Fiore, The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects , Co-ordinated by J. Agel (New York: Bantam Books, 1967), 74-75. ↩

Marshall McLuhan stated that often when a new technology is introduced, “we look at the present through a rear-view mirror. We march backwards into the future.”1 Perhaps this best describes my own current dilemma. As a fifty-three year old photographer, I cannot decide which is more poignant: the innovation or the obsolescence; the emergence of a new technology which irrevocably changes photography, or the abrupt and rapid breakdown of a century-old industry which embodies the medium’s material culture passing into history at a rate that I find difficult to comprehend. This paradox has informed my view of events related to the creative destruction of photography as I’ve known it, including in the city of Chalon-sur-Saône.

Located in the Burgundy Region of France, Chalon-sur-Saône is a beautiful city steeped in history, particularly photographic history because it was here, in 1827, that Joseph Nicéphore Niépce created the first viable process for fixing the image of the camera obscura, which eventually lead to photography as we know it today. However, I was not only drawn to Chalon-sur-Saône by the history of photography, but also recent and radical changes to the medium that Niépce had launched.

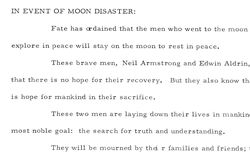

On the early morning of 14 December 2007, I arrived at a cordoned off parking lot in a dreary industrial park on the edges of the city known as the birthplace of photography, to observe an event that has been described as signalling its death. This event was the final chapter in a series of implosions scheduled by the Eastman-Kodak company, the world’s largest manufacturer of photographic products. In recent years, Kodak had been caught off-guard by the speed and effectiveness of newer digital systems that had quickly and drastically reduced the demand for their products. As a result, Kodak had been forced to undertake a mammoth transformation aimed at re-inventing itself as a digital company, and this transformation involved massive layoffs, corporate restructuring and the demolition of hundreds of buildings previously used to make light-sensitive films and papers.

By the time I arrived at Chalon-sur-Saône, I had already attended a number of these demolitions in Rochester, New York, and become familiar with a kind of routine at these events. These implosions were always public and the deliberate destruction of these enormous factories was guaranteed to provide a rare spectacle like that of a solar eclipse or maybe a public hanging. Kodak had always been careful for some reason to put an upbeat spin on these occasions, which I found verging on the surreal. On that day, as I dutifully set up my equipment to record the significant moment on film, I was struck by how my camera was more similar than different to the one used by Niépce 180 years earlier. As the one minute warning siren sounded, indicating the demolition team was about to set off 950 kilograms of dynamite that had been carefully embedded into the structure of the building, I loaded my first film holder and I picked up my cable release. It was astounding to experience these enormous structures, most of which had manufactured film for about a hundred years, coming down in a manner of seconds. In about a six month period in 2007, Kodak carried out several of these scheduled implosions, redefining its relationship to a history it didn’t want anymore. It is remarkable how quickly they were able to rid themselves of it.

-

Marshall McLuhan and Quantin Fiore, The Medium is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects , Co-ordinated by J. Agel (New York: Bantam Books, 1967), 74-75. ↩

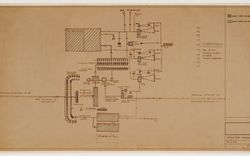

I began the project at Kodak Canada in 2005, when Kodak first announced it was going to shut down their Mount Dennis plant, in Toronto. I asked Kodak if I would be able to document the complex and they said “sure!” I started working in June of 2005, and I was suddenly given amazing access to an expansive suburban industrial space: eighteen buildings on a 5.5 hectare site. It had its own generating station for power. It used to have its own full-time doctor and dentist. It had a whole building dedicated to the employees with a gymnasium and exercise rooms, and that’s where the employee dark-rooms were. The buildings where they made film, which had protected the trade secret that once made the company so profitable, were perhaps most interesting. The main film plant in Kodak Canada was a large, white industrial building. No windows of course, to keep out the light; it is filled with black rooms where all the activity took place in the dark. All the coating of film took place in the dark, all the cutting of that film and paper took place in the dark, and all the packaging. These black rooms are very specific to the medium of photography, meaning the buildings can’t be easily repurposed. They’re not like, say, textile mills from the nineteenth century that make great artists’ studios and restaurants.

After the Mount Dennis plant was demolished in 2007, I began to suspect that perhaps I wasn’t just documenting the closing and demolition of a specific plant, but that I was in effect documenting the disappearance of film; of the thing, of the material that I used to make pictures. I went on to make a series of pictures of implosions at Kodak plants, including in Rochester, New York, where Eastman-Kodak headquarters are located, and across Western Europe, including in Chalon-sur-Saône. The photograph I took from that implosion was created as an installation for the north facade of the CCA, and I decided to present it as this large kind of Polaroid. It’s a specific positive-negative peel-apart Polaroid image on the facade of the building because one, I really wanted to address this impending obsolescence of this material, which is now gone: you can’t get it anymore. I also wanted to kind of bring forward that idea of what photography has been; that quality of the medium.

My photographs of the disused factories and of the implosions rely on photography’s most important attributes: its ability to describe accurately and in detail. They are meant to serve as records, documents and authentications of these events—I was there, this is what it looked like, here’s a photograph to prove it. However, I believe they not only signal the end of photographic film but also our relationship to physical media in general. At the implosion sites, I was probably the only person making photographs on film; if we look into the crowd, we see digital capture devices of all kinds glowing with displayed images of the events unfolding before them. By this time, the electronic chip known as the charge-coupled device, or CCD, had usurped the previous role of photographic film. Faster, cheaper and more flexible for most societal applications that have used film in the past: it’s not only a newer technology but quite simply a better one.1 As early as 2002, it matches the quality of film and it is affordable enough to be employed in both mass consumer and professional markets, creating a domino effect in the global photographic industry.

-

The CCD chip was invented in the late 1960s at the Bell Research Labs in New Jersey by Willard Boyle and George Smith, who both received the 2009 Noble Prize in Physics for the invention of this device. ↩

In 2004, Ilford Photo, a UK company established in 1879, seeks protection for corporate restructuring. A year later, AGFA Photo, based in Belgium and Germany with roots reaching back to 1867, declares bankruptcy and ceases all manufacturing operations in December 2005. Around this time, Eastman-Kodak quietly announces that it would no longer manufacture a product it had been involved with since 1889: black and white photographic papers. In October of 2005, Kodak also announces that its sales of digital products had surpassed that of staple photographic films, papers and chemicals, and that the company planned to cut 25,000 jobs from its worldwide operations in response to a loss of one billion dollars in its third quarter. Two months later, Nikon publicizes its plan to stop manufacturing film cameras. One week later, Konika Minolta Holdings, a Japanese stronghold in the world of photography since 1903, announces it would cease operations.

Finally, in 2008, the Polaroid Corporation announces that it was throwing in the towel and would be closing its instant film factories. We no longer need the Eastman-Kodak company to develop the photos we take with digital capture devices, because these devices also process the images, display them immediately, and allow us to distribute them through a wireless network to a global audience. Digital capture devices do not use film or any other kind of media in a traditional sense. I can’t see their inner workings or touch the material that creates images, texts and sounds. In fact, I must constantly remind myself that digital capture is not another evolutionary improvement in photography: it is a new medium altogether. It’s data, binary code, algorithms. Simply put, it is the new world of information.

As I struggle to comprehend a medium that is both abstract and concrete, immaterial and material, I also continue to make photographs in a hybrid world where film and electronic imaging technologies co-exist. At least for the time being. Every time I pull out my large format view camera, it feels somehow more dated, more a tool that I can no longer use. Cameras, without film, are useless; museum pieces. In “Photography in the Age of Information,” Martin Lister writes:

Whether photography is mechanical or digital, whether optical cameras are used or not, we should expect I think to find signs of photography moving simultaneously in different directions. In its new technological environment, photography will be bent to new ends while it struggles to retain its historically defined purposes.1

For me, this quote really describes the past few years when so many changes happened so quickly, and I find myself at one moment looking to photography’s past to figure out what it has been, and in the next moment looking to the future, trying to figure out what it’s becoming or what it’s going to become. It’s really difficult these days to define photography’s present tense.

-

Martin Lister, “A Sack in the Sand: Photography in the Age of Information,” Convergence 13, no. 3 (2007): 251. ↩

This essay is adapted from a lecture delivered by Robert Burley in 2010, during his residency as CCA Mellon Senior Fellow. Robert Burley curated the exhibition The Disappearance of Darkness and its accompanying murale installation Photographic Proof, on view at the CCA in 2009.