Expertise in the Comfort Zone

Text by Gareth Hammond

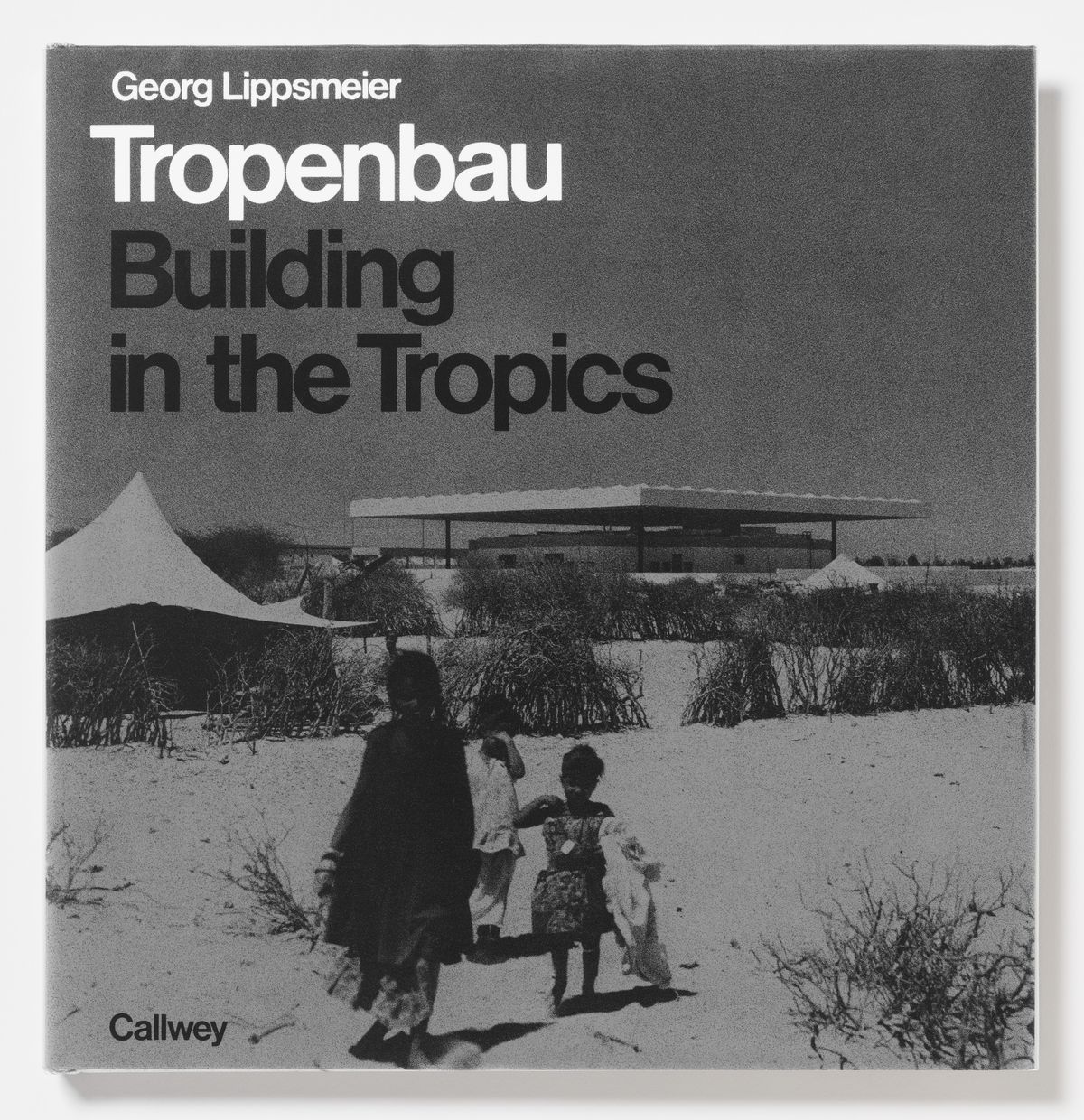

The legacy of German architect and tropical building expert Georg Lippsmeier, is enigmatic. While he remains mostly unknown in architectural discourse today, he is considered to be one of the most successful practitioners of tropical architecture operating in the mid-twentieth century.1 Lippsmeier operated across the Global South,2 with commissions in Africa, Asia and South America, and also designed the German Pavilion for the 1992 World’s Fair. Parallel to his architectural practice, Lippsmeier founded the Institut für Tropenbau (IFT), based in Starnberg, Bavaria, which published a number of manuals and reports related to tropical architecture, the most notable being Tropenbau=Building in the Tropics, first published in 1969.

To support the IFT’s publishing activities and parallel architectural practice, Lippsmeier amassed an extensive research library of over 4000 titles. This library, now part of the African Architecture Matters Collection at the CCA, is one of the largest known collections of books related to architecture in Africa. It also represents the diverse interests of the foreign expert and contains a wealth of books, periodicals, development reports, conference proceedings, manuscripts, articles, and dissertations, spanning various topics related to planning and construction in the Global South. Through this diversity of materials, the IFT library presents a snapshot of the sources of information used by European experts working in the Global South during the second half of the twentieth century. The range and diversity of the IFT library is demonstrated by the bibliography of Tropenbau, arguably the most complete of any manual on tropical building at the time of its publication.3

Read more

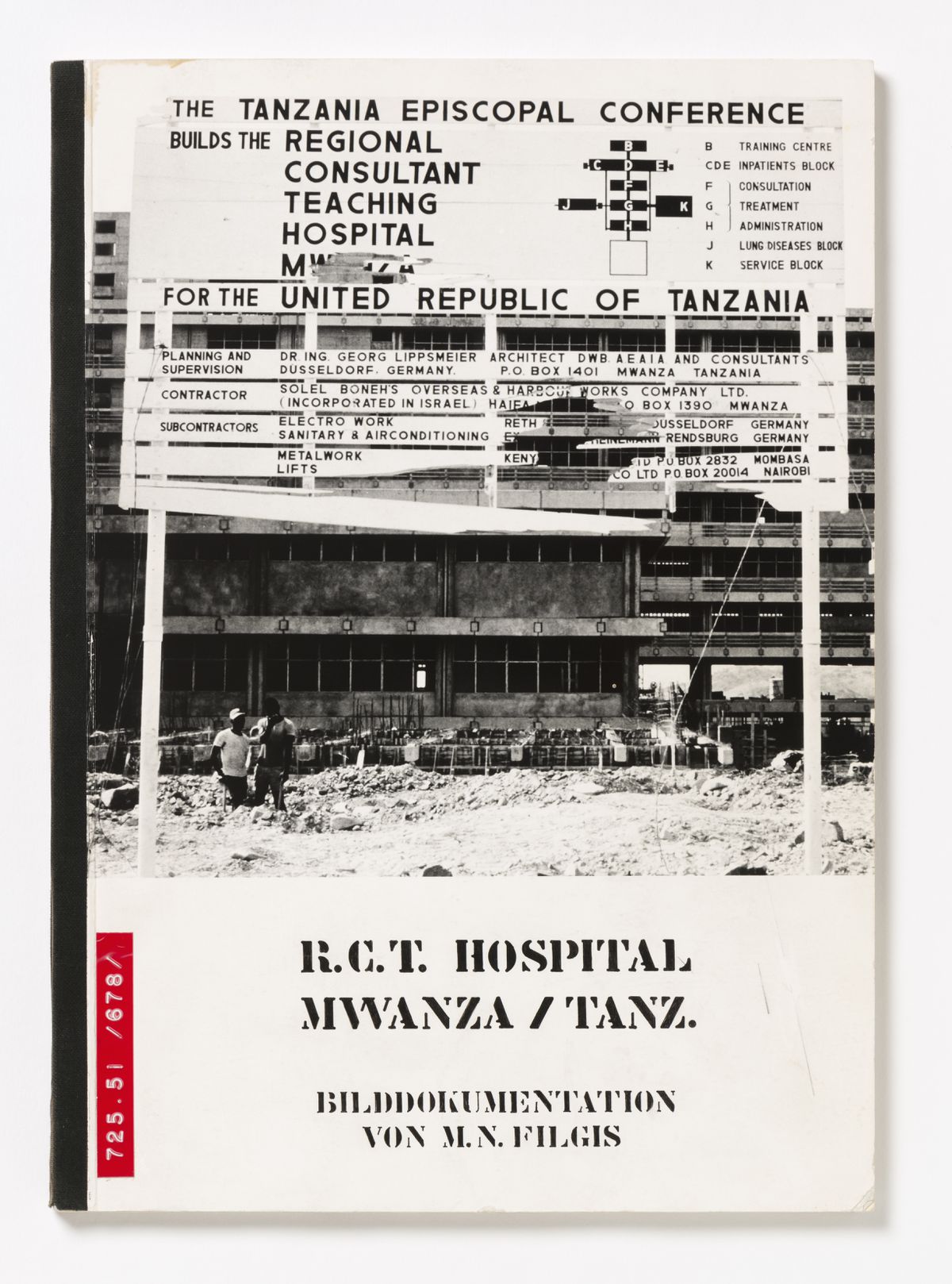

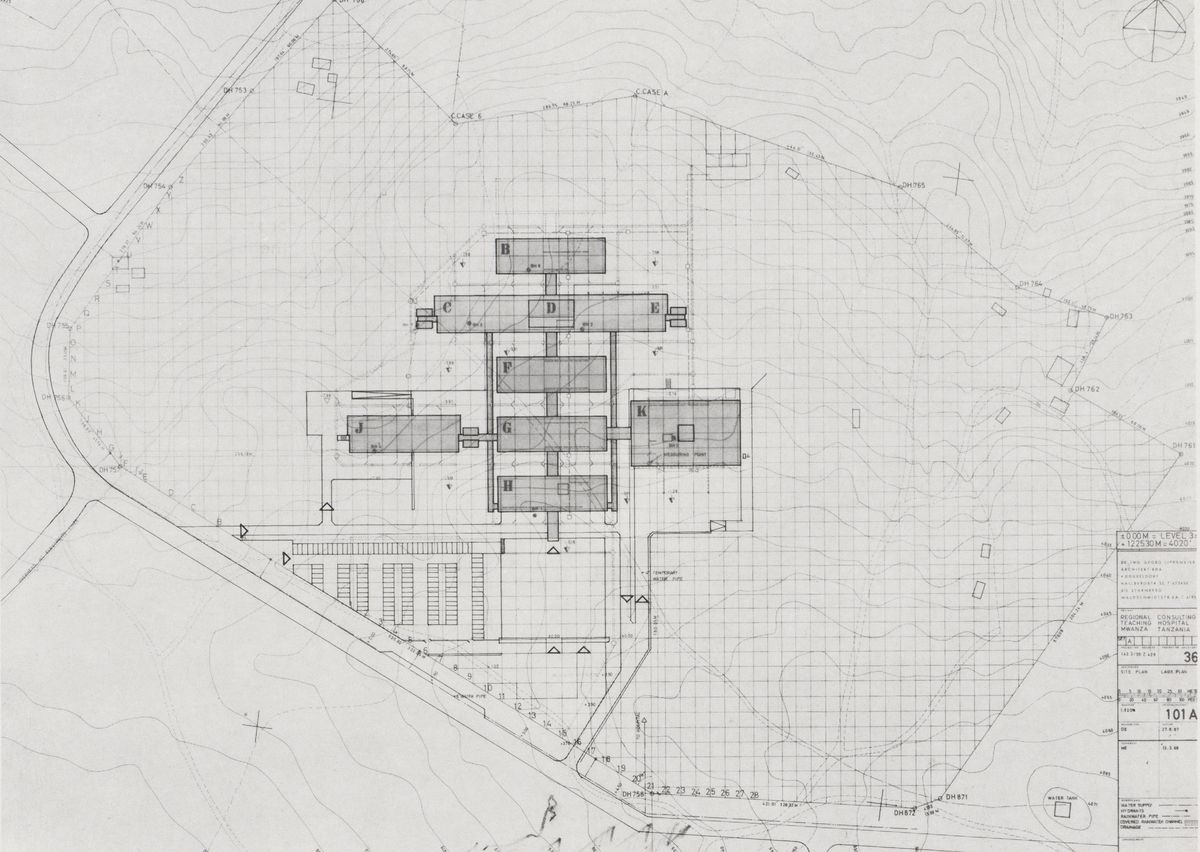

In 1969, the same year as the first edition of Tropenbau, Lippsmeier + Partner Architekten opened their first field office in Mwanza, Tanzania, to oversee the construction of the Regional Consultant Teaching Hospital (later renamed the Mwanza General Hospital). Construction was financed by the Tanzanian Episcopal Church and ownership was transferred to the government of Julius Nyerere in 1973, fulfilling a development goal set out by the Second Five-Year Plan of Tanzania, aimed at restructuring the recently independent country to participate within the global economy.1 This plan was inspired in part by the Ujamaa movement, a socialist campaign that drew its name from the Swahili word for “brotherhood” and sought to create a new national identity uniting Tanzanians above their many distinct ethnic and tribal groups. Although Tanzania remained fiercely independent during this time, President Nyerere was adept at securing financial aid from foreign nations, often drawing from competing Cold War states. West Germany, for example, saw the dispensation of aid as a way to secure the former colony of Tanzania as a promising future trading partner once the new nation was able to stand on its own. Much of the German aid came in the form of expertise and infrastructure with the goal of providing Tanzanians with the basic means to further develop as an independent nation, including in the Mwanza General Hospital project led by Lippsmeier.

-

Tanzania. Tanzania Second Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development, 1st July, 1969-30th June, 1974 (Dar es Salaam: Government Printer, 1969). ↩

When work began on the Mwanza General Hospital, there was one doctor for every fifty thousand people living in Tanzania. The average life expectancy was below fifty years, less than two thirds that of most countries of the Global North.1 For the Tanzanian government, improving medical infrastructure was critical for raising life expectancy and essential to economic progress across the nation. This created an opportunity for Lippsmeier + Partner to become heavily involved in the development of healthcare infrastructure projects in Tanzania, prompting the IFT library to acquire a wealth of publications related to hospital design at that time.

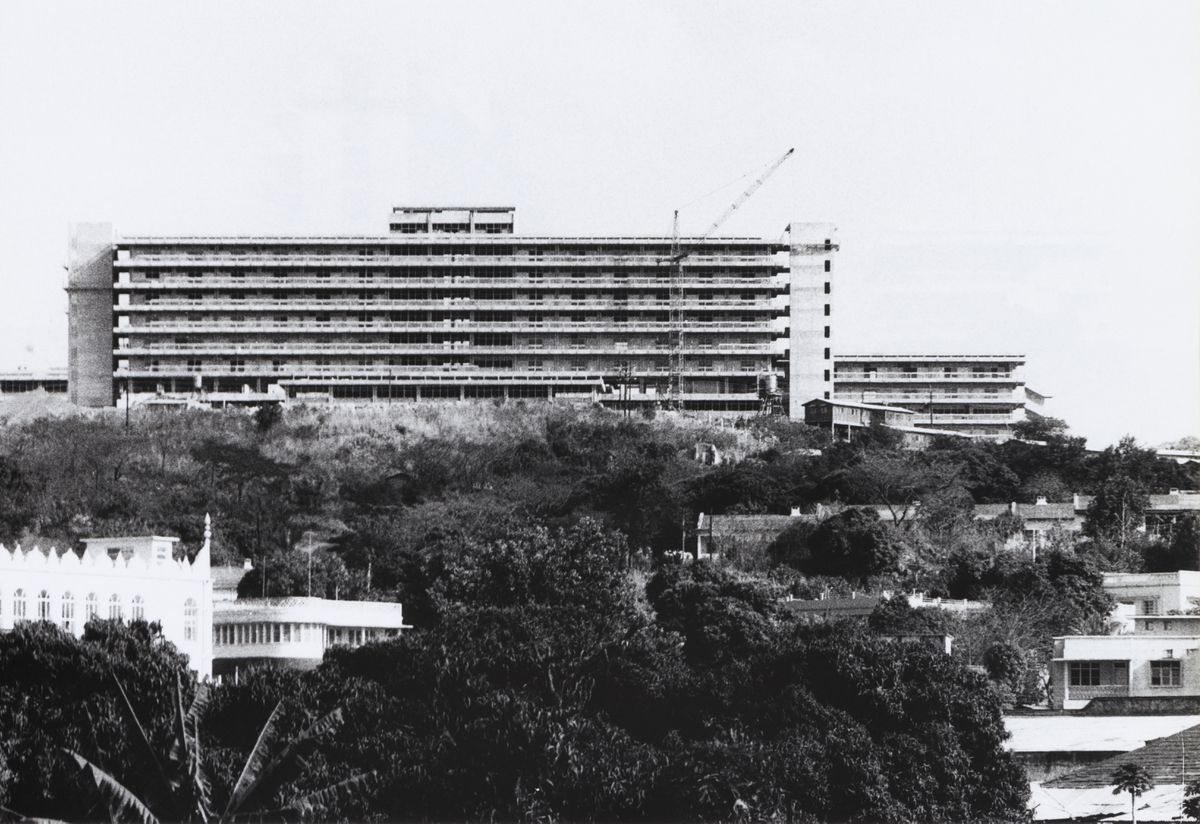

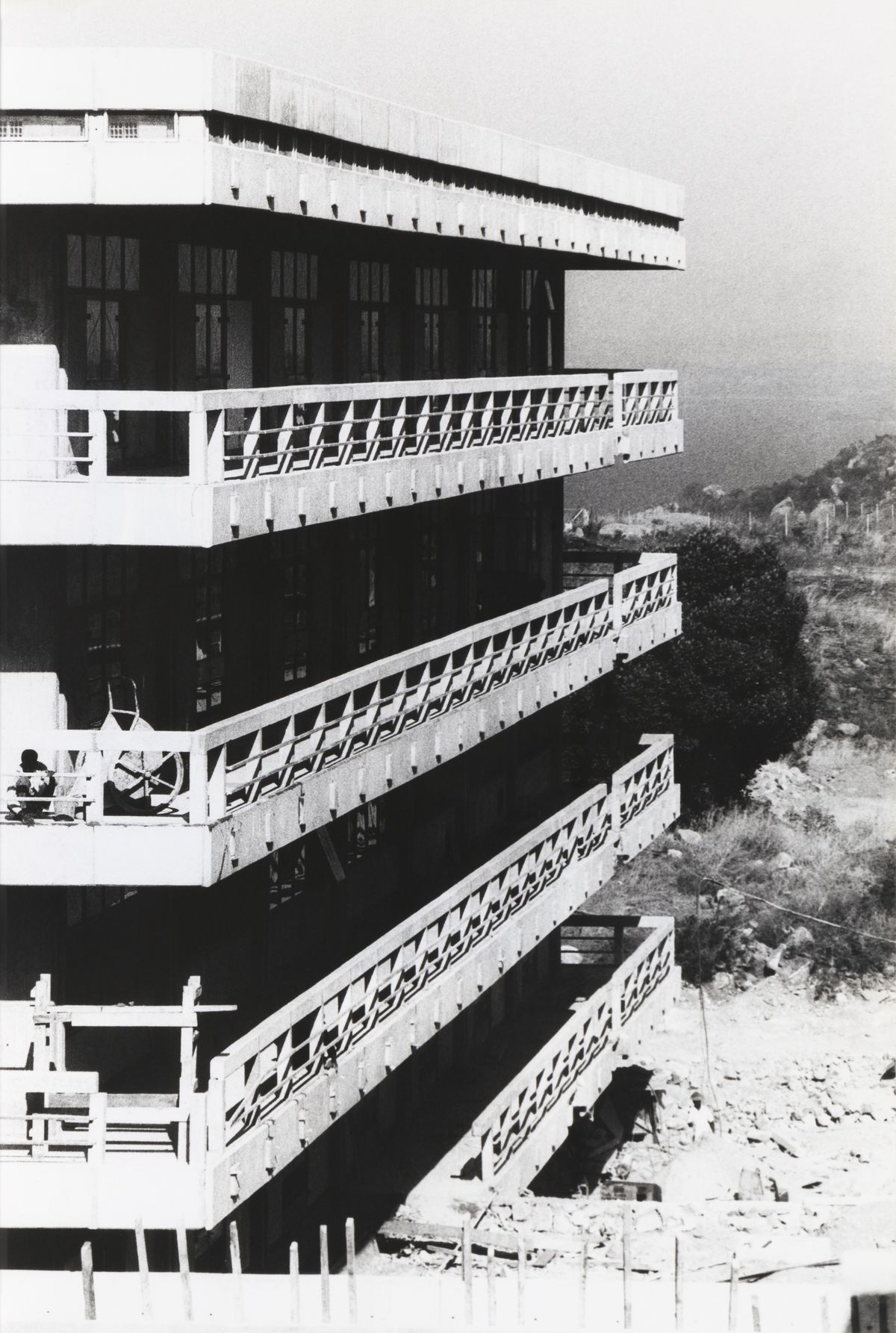

The architecture of the Mwanza General Hospital shows little apparent formal relation to the site or to Tanzanian culture, forms, or materials. Sitting on a hill, the imposing nine-storey concrete ward tower appears to signal a new beginning for a nation that aspired to improve healthcare outcomes and to modernize, following the new ideology stemming from national independence. At the same time, although it is difficult to determine why the Hospital looks the way it does, the building itself could be read as both a symbol of progress and a banner advertising future trade relations with West Germany. Further, the construction of a teaching hospital in Mwanza represented an opportunity for the development of expertise on many fronts.

Judging from the diversity of books related to indigenous and vernacular architecture in the IFT Library, it is clear that Lippsmeier was familiar with, and even impressed by, the diversity and sophistication of building techniques within the Global South. Although most publications within the IFT library on the topic of indigenous and vernacular building techniques are by authors from the Global North, they present a valuable archive of information and ideologies. Likewise, although the finer nuances of traditional architecture might have been overlooked by foreign authors, these publications pay close attention to the importance of solar shading and natural ventilation in creating habitable vernacular architecture in tropical regions. For millennia, these two principles have guided the construction of buildings between the Tropics of Capricorn and Cancer, which have functioned successfully without mechanical air conditioning. In designing the Mwanza General Hospital, Lippsmeier took these principles into account, while also implementing a new quantitative methodology for relating the building to the environment in which it sits.

Built on the shore of Lake Victoria, the hospital was designed to take advantage of the natural breeze and to operate with minimal mechanical systems, which Lippsmeier argued were prone to failure and relied on electricity that was often scarce, if at all available. Instead, by physically responding to local climatological trends, the hospital enclosed its own “comfortable” microclimate. In Tropenbau, Lippsmeier outlines a process to design buildings suitable for a certain tropical climate, in three phases: information, analysis, and design.

-

World Bank data catalogue, accessed 12 December 2017. ↩

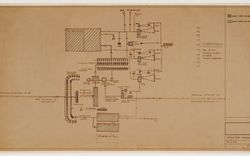

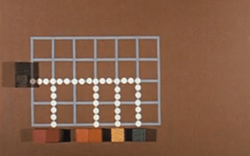

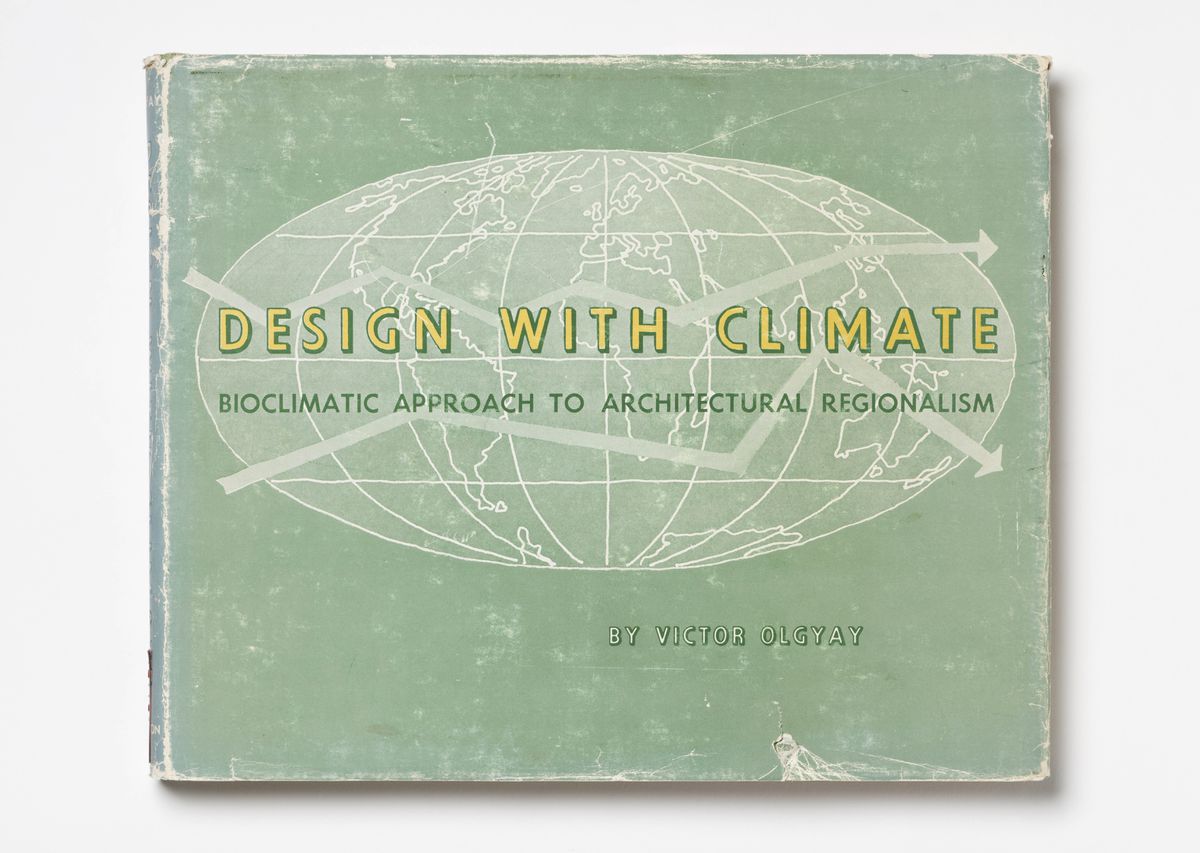

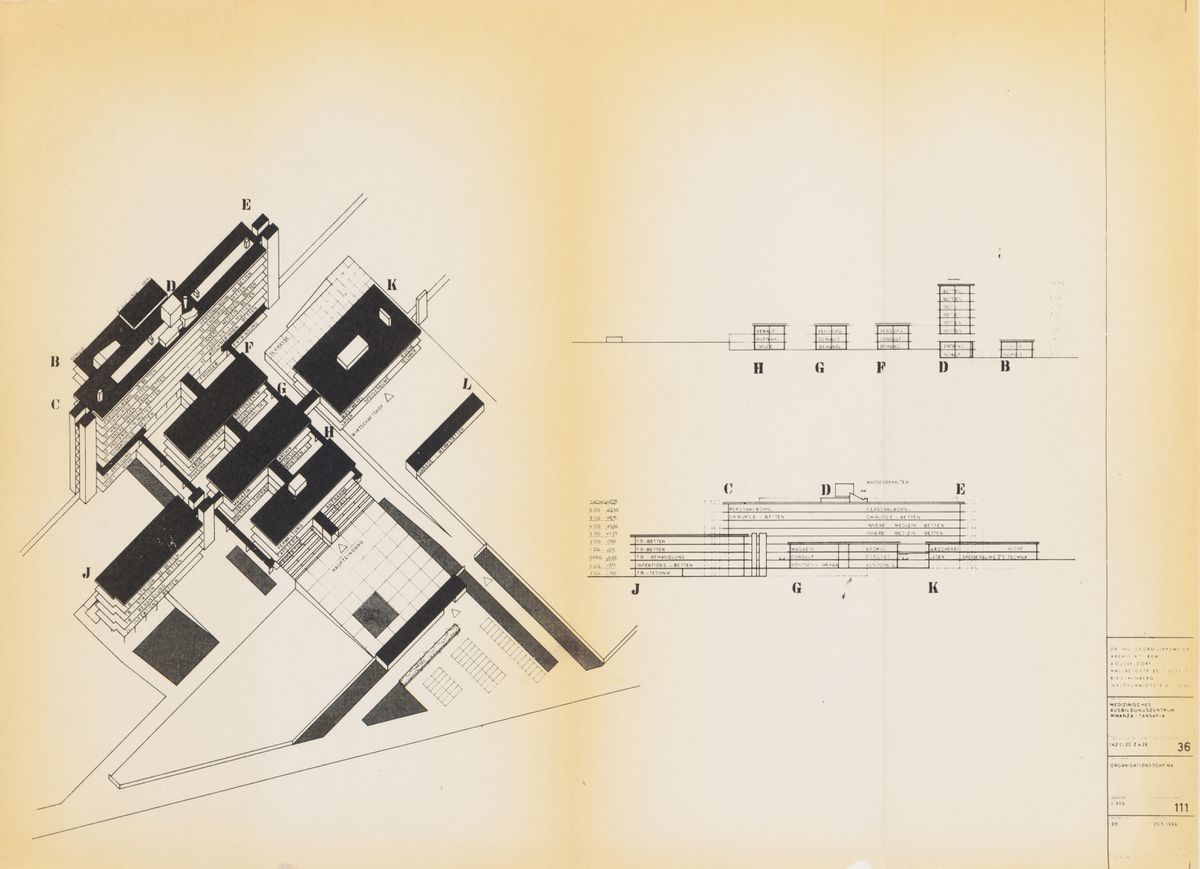

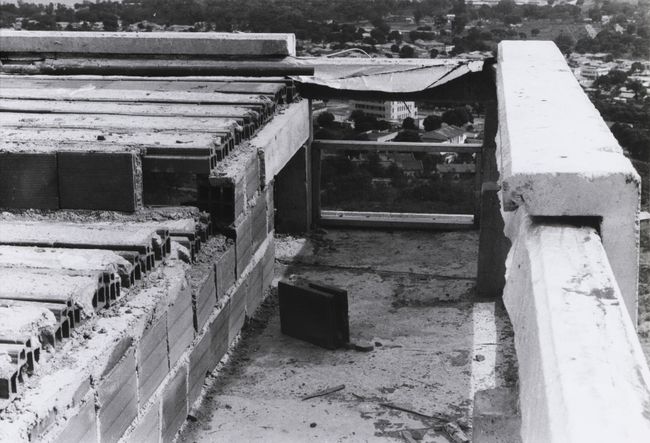

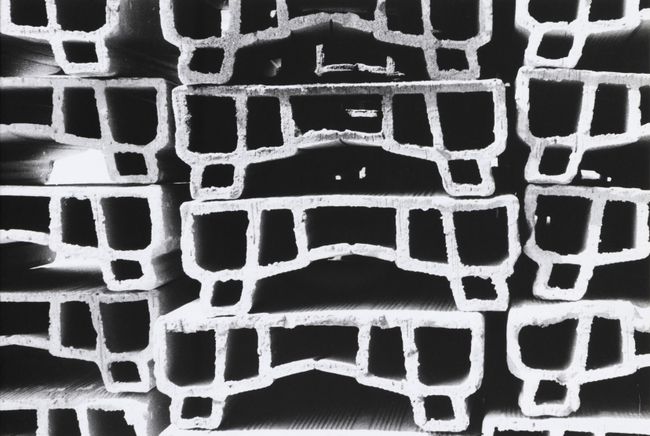

This method synthesizes approaches from previous works on tropical architecture1 and presents a highly systematized approach congruent with the climate-driven design philosophy of the Architectural Association School of Tropical Studies.2 According to Lippsmeier’s approach, the major tectonic expression was driven by location-specific climatic design requirements, in this case ensuring that the facades of the Hospital were exposed to minimum solar radiation and that the enveloped enclosed a zone of climatic comfort. Lippsmeier determined these requirements by relating site-specific information and local climatological data to two types of diagrams representing solar path and thermal comfort. He then arranged the orthographic layout of the plan with respect to a diagrammatic representation of the apparent solar path specific to Mwanza, providing an architectural volume with minimal surface area exposed to direct sunlight. Cantilevered balconies, functioning as brise-soleils, project outward from the facade at a distance derived through graphic calculation, so as to completely shade the primary mass of the hospital, except for during the coolest months. Furthermore, lifts and stairwells are located at the east and west ends to provide a buffer space between the primary volume of the building and the surfaces with greatest exposure to solar radiation. In this way, the logic of the building in plan emerges directly from a gnomonic projection of the sun relative to the hospital. While this practice of orienting buildings with respect to sun-path is an ancient one, and almost all vernacular architecture in warm climates presents a locally specific strategy to mitigate solar heat gains, Lippsmeier’s use of solar diagrams provides a specialized method of expertise. Furthermore, Lippsmeier organized the buildings of the Mwanza General Hospital following the underlying mechanics of the modernist grid derived from European planning techniques.

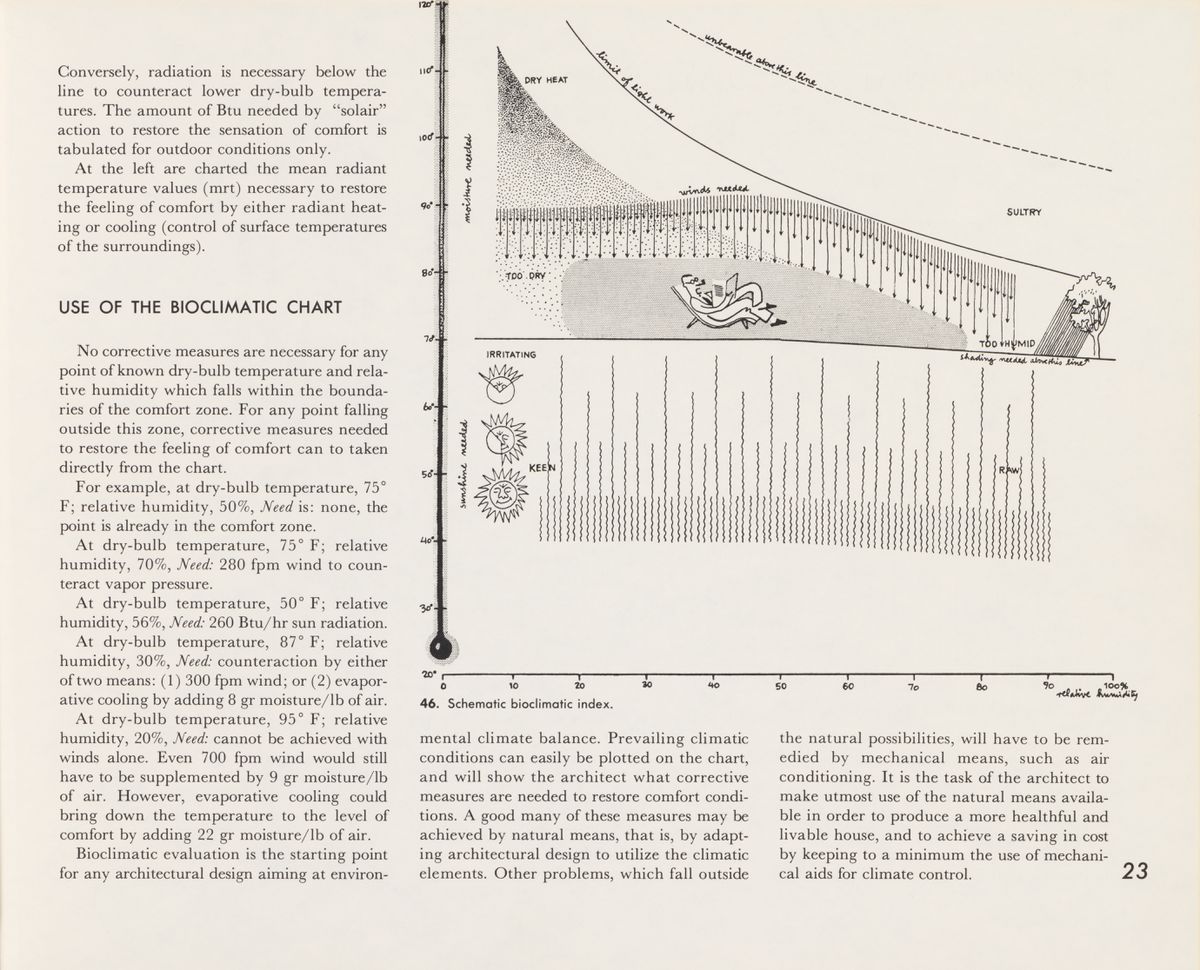

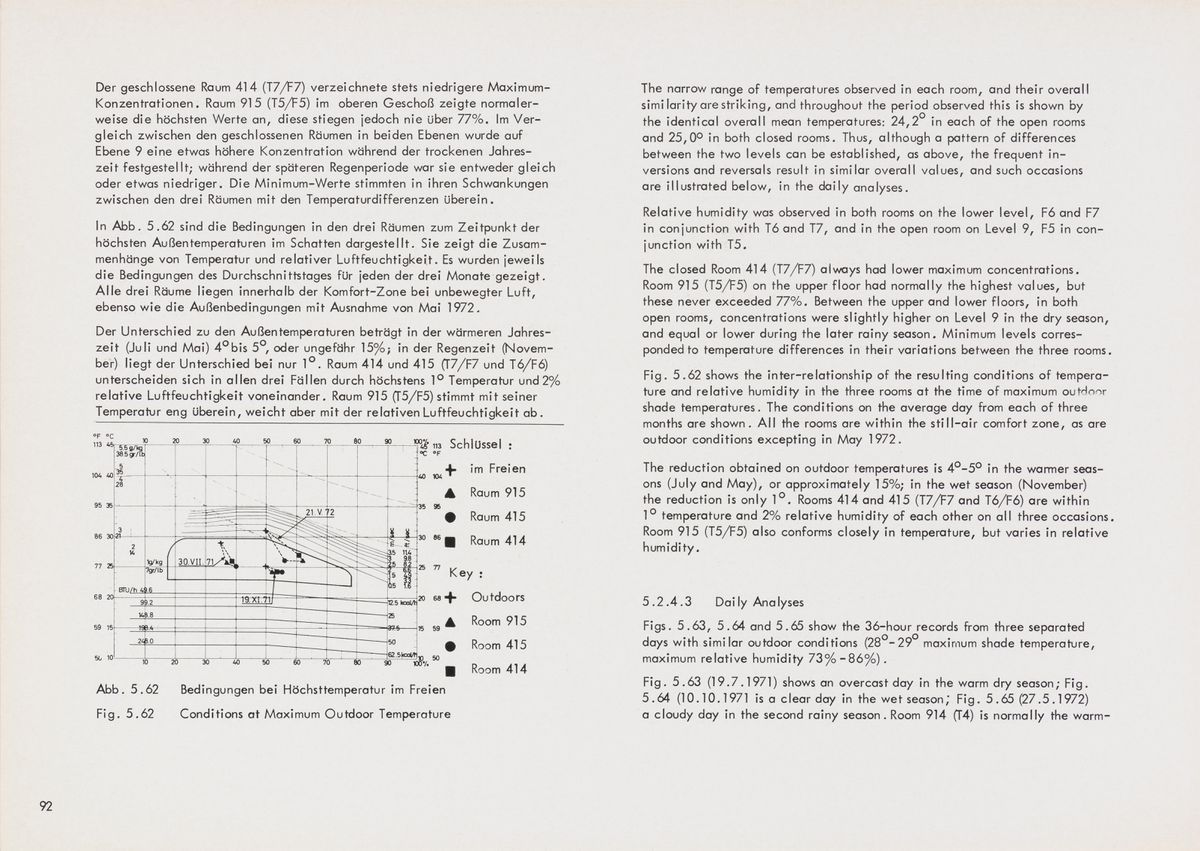

Beyond orientation with a solar grid and the use of balconies as brise-soleils, Lippsmeier justified other design choices, such as the construction method, the materials, and the envelope design, as part of a climatic strategy that would keep the temperature and humidity of building interiors within a specific comfort zone solely by “natural means.” He derived this strategy from a graphic overlay of numeric data related to meteorology, psychrometrics, and human physiology to create a precise spatial field on to which the envelope of the hospital should hypothetically enclose. However, in practice, the alignment between the theoretical comfort zone and the realized interior microclimate of the completed building depended greatly on the expert’s intuition and subjective interpretation of the climatic data. Lippsmeier himself explains this sort of educated guesswork in Tropenbau, stating that “a comparison of [meteorological data] together with a combination of experience and deduction produces useful results.”3 In this way, the climatic diagrams function more as tools of divination than as precise scientific instruments. On further consideration, it becomes apparent that highly empirical climatological modelling and precisely calculated climatic comfort charts, while useful in designing mechanical air-conditioning systems, provide little predictive power of user comfort when the building itself is expected to function passively using natural breezes. In his effort to design a “naturally” ventilated building using the same tools as a mechanically controlled air-conditioned building, Lippsmeier’s design process was based on problematic assumptions about the way natural systems function, derived from two-dimensional graphic representations of climate.

-

Victor Olgyay. Design with Climate: Bioclimatic Approach to Architectural Regionalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963). ↩

-

Jiat-Hwee Chang. Genealogy of Tropical Architecture: Colonialism, Ecology and Technology (London: Routledge, 2015). ↩

-

Georg Lippsmeier and Kiran Mukerji. Tropenbau (Munich: Callwey, 1980), 61. ↩

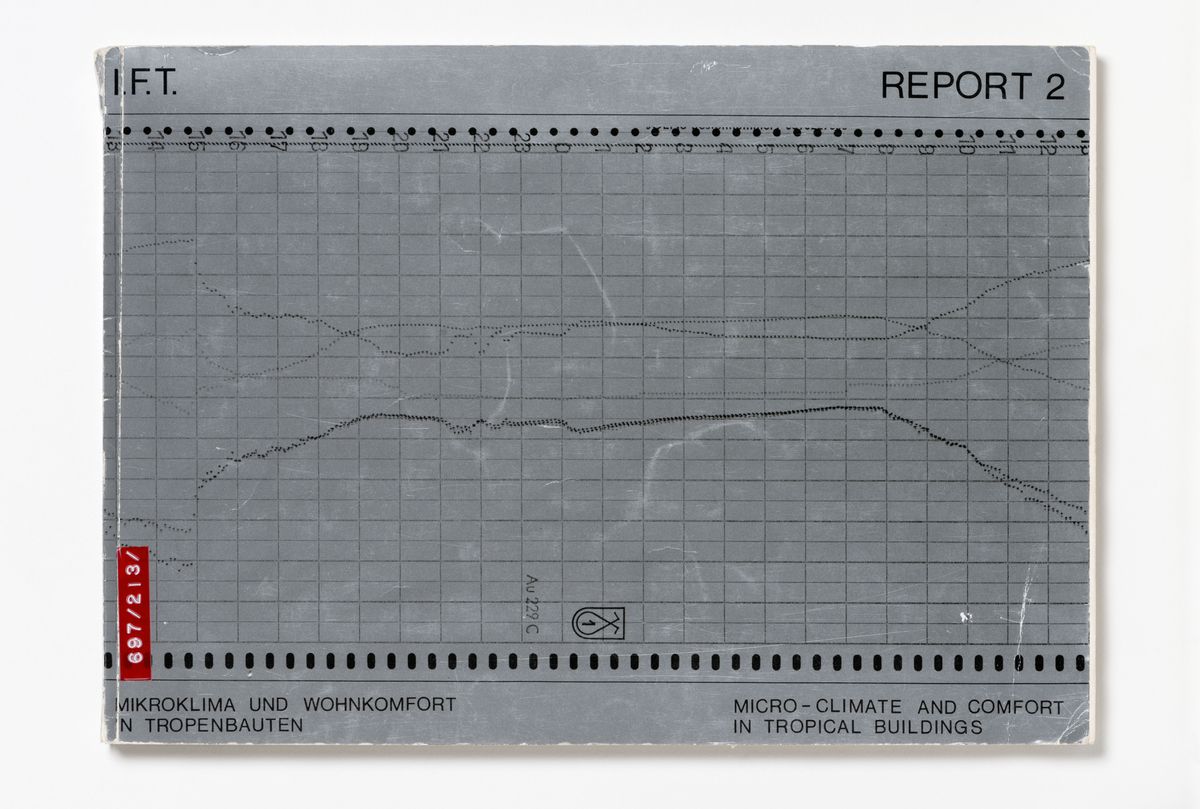

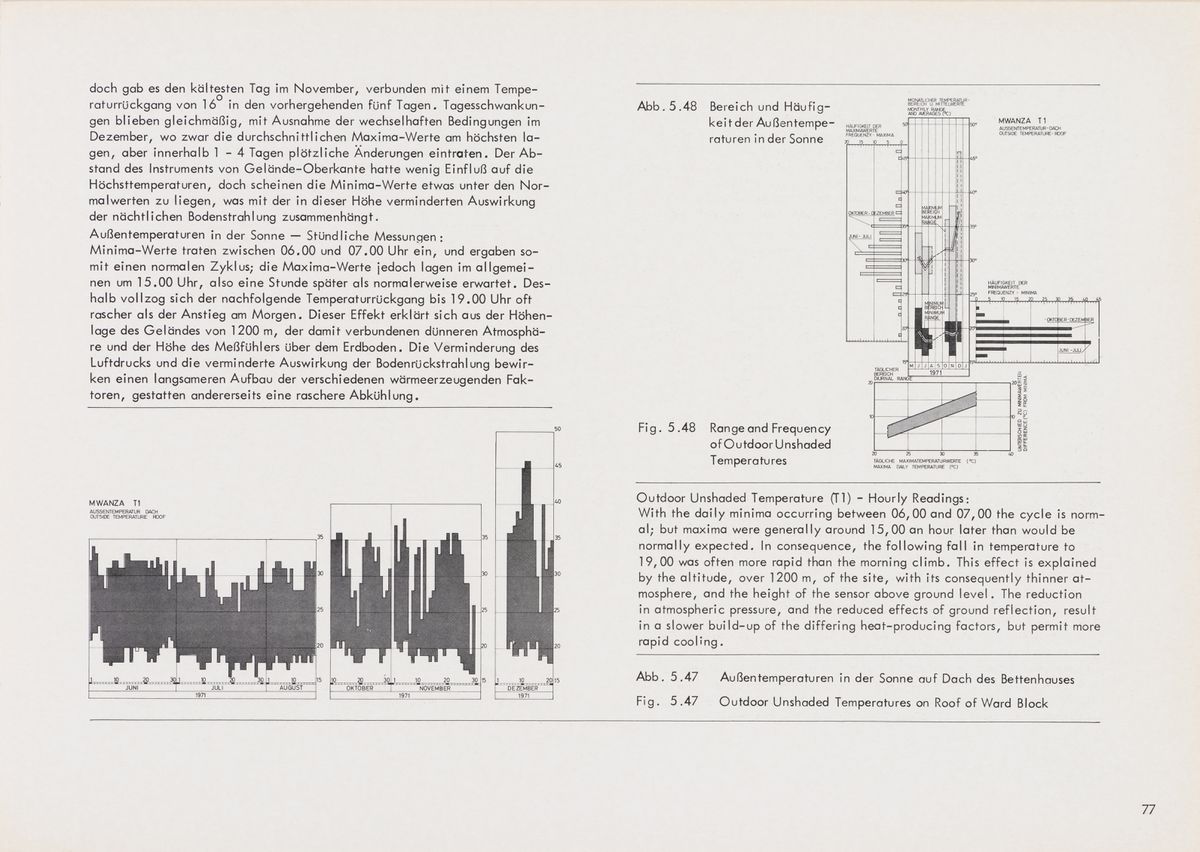

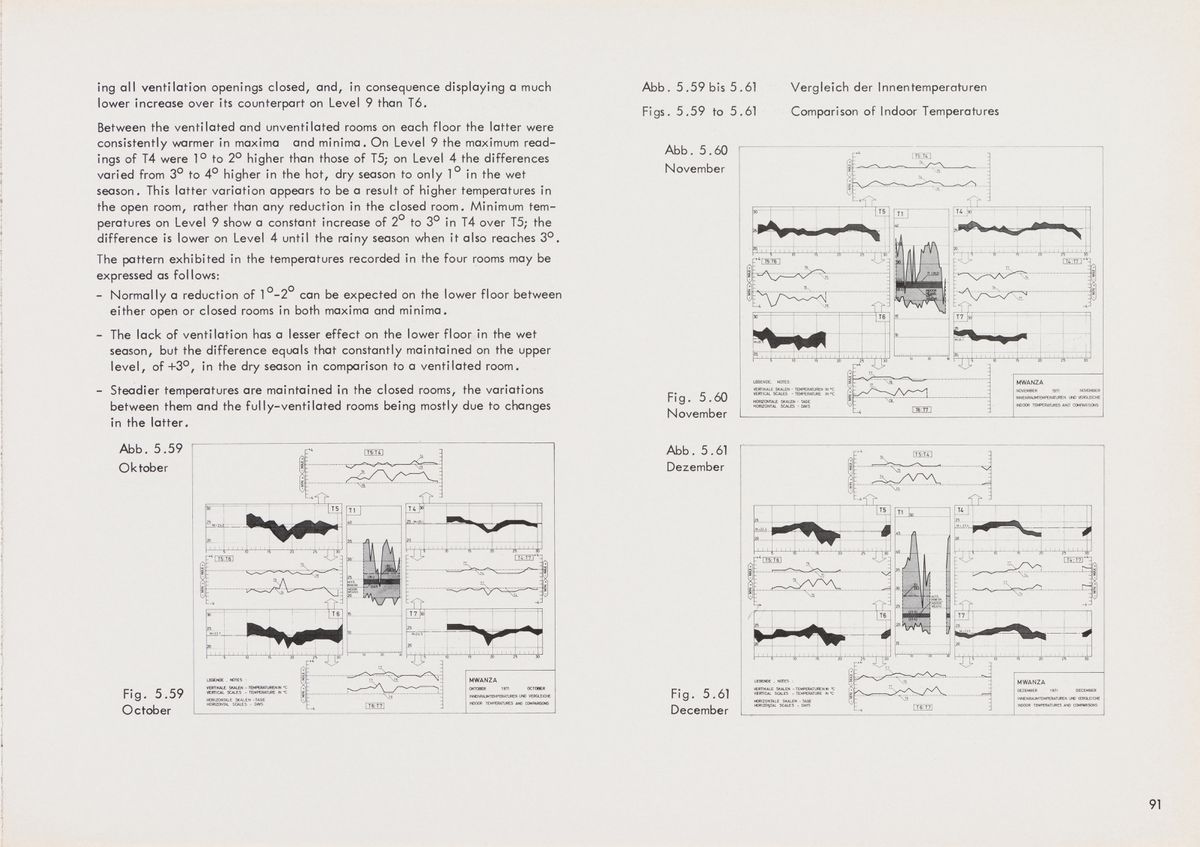

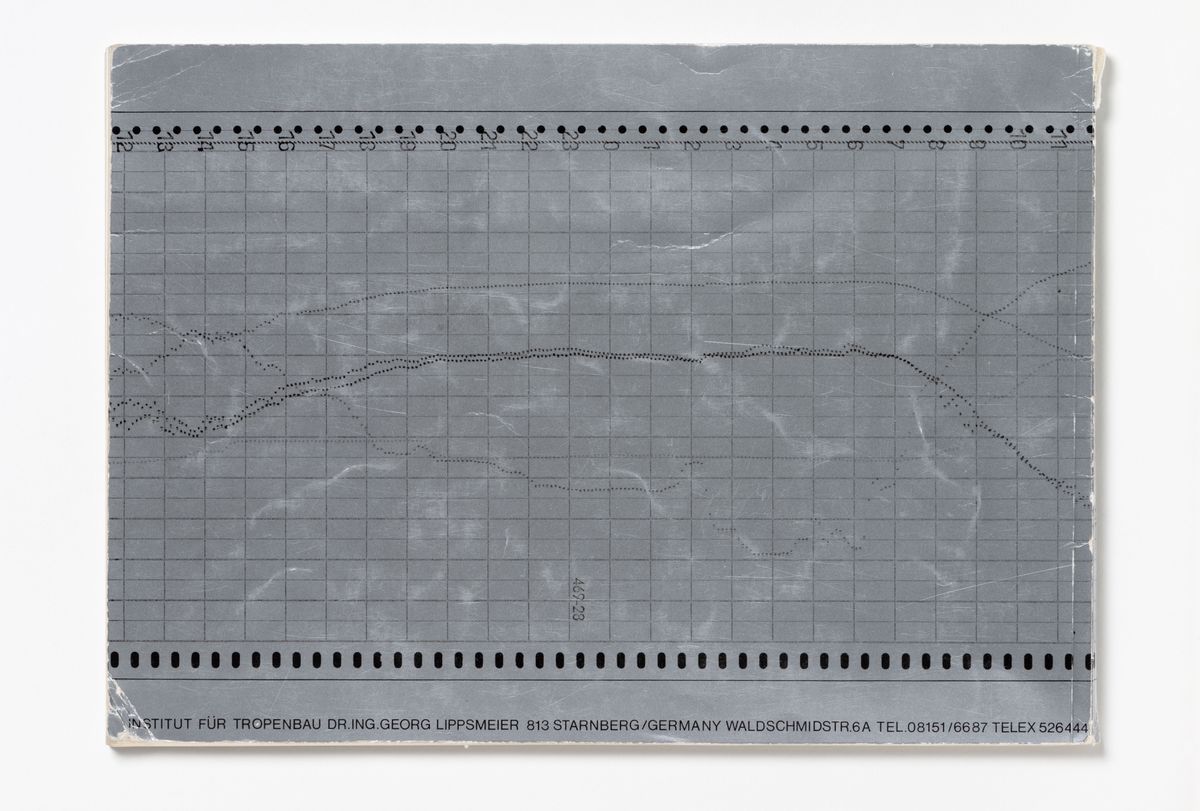

In 1973, Lippsmeier’s success in correcting the misalignment between the graphic representation produced by his team and the actual climatic conditions in the Mwanza General Hospital was examined in an IFT report on the microclimatic performance of the building. The IFT report, Micro-climate and Comfort in Tropical Buildings, provided a revised analysis of thermal comfort within the Mwanza General Hospital to assess the relationship between the architecture and the degree to which it addresses the specificity of the local climate. Over the course of a year, the IFT monitored the performance of the Hospital through a purely quantitative methodology. The report offered tables and charts representing numeric data on temperature and humidity generated by sensors, interlaced with dry climatological commentary, to state the effectiveness of the Mwanza General Hospital at maintaining an interior microclimate within the climatic comfort zone. The report thus purported to provide evidence of Lippsmeier’s success in building for climatic comfort, without taking into consideration the lived experience of the Hospital’s occupants.

More critically, the report flattened the complex relationships between climate, culture, and comfort and reduced them to numeric variables. This might have created the illusion of science, but it failed to follow the control or rigour required for a methodology to be considered scientifically valid. Further, by using complex composite figures to describe changes in the interior microclimate over time, relative to the exterior meteorology, the IFT created a need for expertise in order to clarify the report’s findings and its opaque representations. The production of overly complex diagrams situates designing for the tropics as a complicated process that can be elucidated by an educated expert through techno-scientific means. However, what the report actually presented was an affirmation of the grid from which the architecture of the Hospital was articulated and according to which its performance was, in turn, studied, using electrical sensors rather than the experience of the people it served. The Mwanza General Hospital acted as an inflection point between the built work of Lippsmeier and the knowledge-generating machine of the IFT. By first creating architecture hypothetically suited to the local climate, and then using reports and publications to provide quantitative evidence of the success of this process, Lippsmeier and the IFT strengthened their claims of expertise with regard to designing suitable architecture for the tropics. In this way, the Mwanza General Hospital illustrates the ambivalence of a methodology based on expertise that ignores local cultures, customs and human experiences of comfort, in favour of instrumentalized standards. The result is an architecture which becomes a physical inscription of the diagrammatic representation of the climatological features of the site, nevertheless dependent on the accuracy and relevance of the analytical models used.

Gareth Hammond developed this research as part of the 2017 CCA Master’s Students Program. This program offers students an opportunity to use the CCA collection during a summer residency. In 2017, it focused on the African Architecture Matters Collection, recently arrived at the CCA.