Territorializations of Dust

Valeria Guzmán Verri on surfing, yoga, and suffocation on the North Pacific coast of Costa Rica

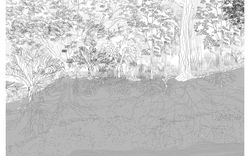

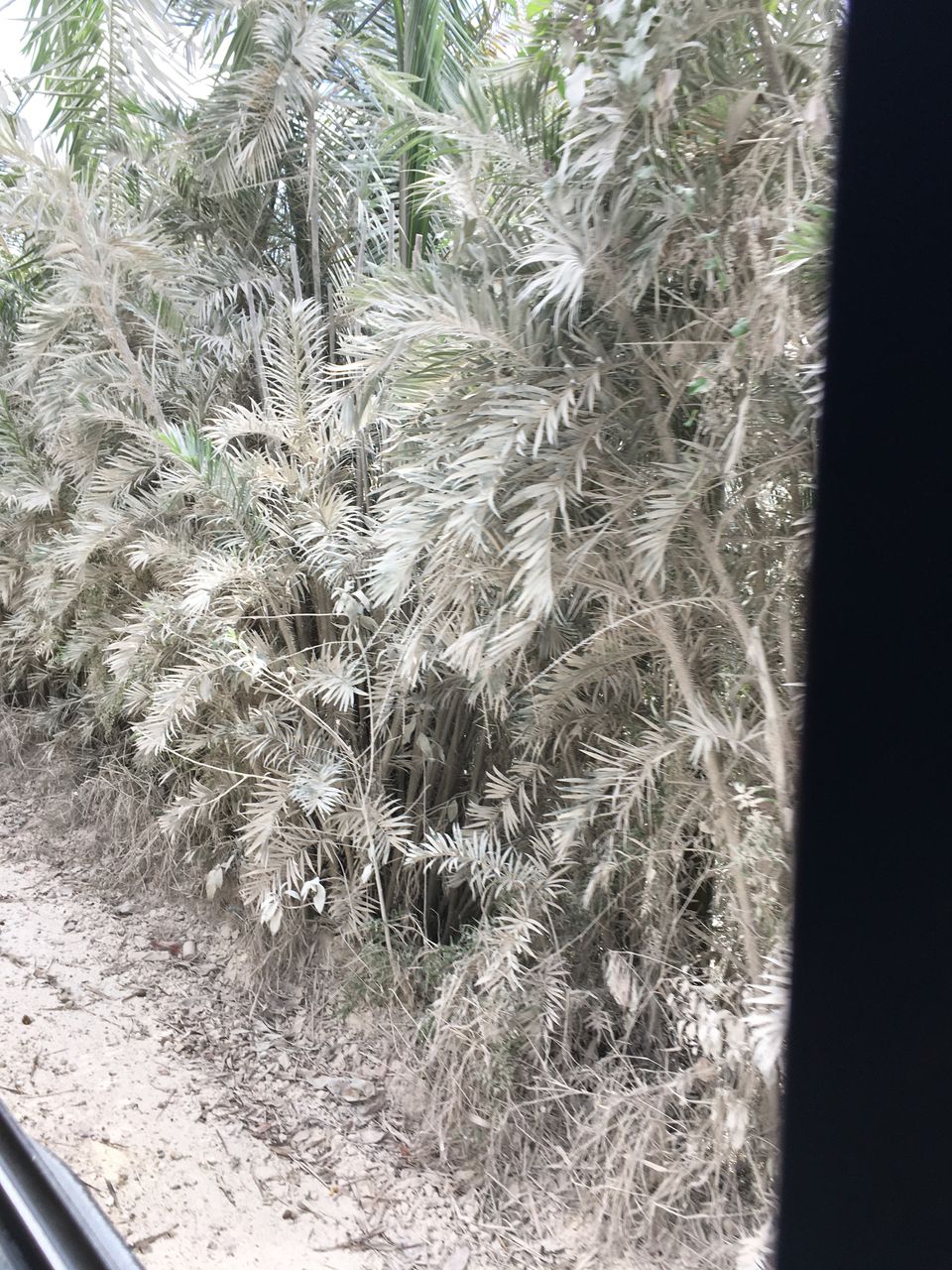

Over the last twenty years, territorialization processes have been reconfiguring the littoral of Costa Rica’s Nicoya Peninsula through dust. During the dry season, the ballast surface of Route 160 disperses dust particles throughout the surrounding houses, schools, health centres, and pastures. Private and public transportation vehicles (cars, trucks, and quad bikes) become the active agents of dust dispersal: the speed and contact of tire on surface causes the powdered ballast to rise and hang in the air, slowly suffocating the unprotected human and more-than-human bodies in its path.1 In some areas the road surface is white, giving rise to a snowy effect as it scatters as powder over a tropical dry forest landscape. The colour is that of the local limestone, which after extraction from nearby mountains is used by the Costa Rican Ministry of Transportation and Public Works for road construction.

Since the late 1960s, Nosara’s coastal area has been a site for a migration of real estate developers and investors, and since the beginning of the twenty-first century it has positioned itself as a tourist destination for surfing and yoga. Dust has become a means to territorialize a field of relations that is reconfiguring divisions between landowners, residential tourists, digital nomads, visiting surfers and yogis, and those who serve the industry—mostly gardeners, cleaners, waiters, dog and baby sitters, tourist guides, tuk-tuk drivers, and construction workers, all of whom find themselves expelled from breathable territories.

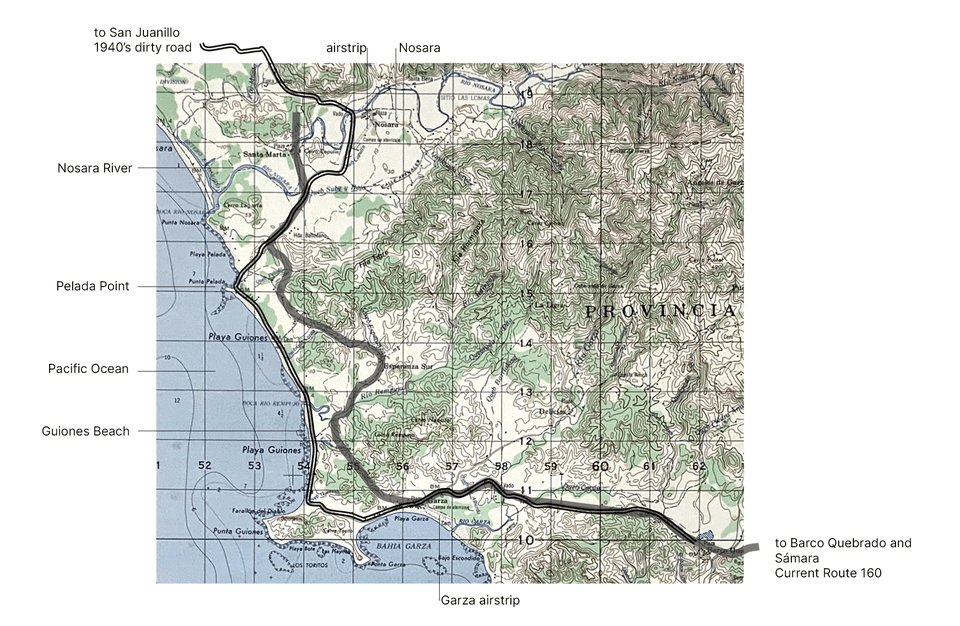

A portion of the road was built by the state in the 1940s to interlink the small villages of Pelada, Garza, Guiones, and Sámara, among others. “In these vast and fertile areas, unrivaled for the cultivation of rice, corn, and cattle ranching, and where fine woods constitute true wealth, the families living there are practically unable to […] obtain primary-need goods,” reads the 1940’s MP petition to the Costa Rican Legislative Assembly, which led to the construction of a dirt road. In the 1957 official topographical map of the area, the road is identified as being passable only during summer months.2

-

Here we follow Pugliese’s deployment of more-than-human as a category that marks “the relational ecologies that constitute the very conditions of possibility for both human and more than human entities.” Joseph Pugliese, Biopolitics of the More-Than-Human: Forensic Ecologies of Violence (Duke University Press, 2021), 3. ↩

-

Legislative Assembly, Decree for construction of a dirt road connecting small villages in Nicoya canton, 1940, Costa Rica National Archive. ↩

One American real-estate agent who has lived in Nosara for twenty years has written with mocking irony that the unpaved route has of late become a protection strategy of sorts, impeding easy access of “thieves” and “Disney world, buffet line, all-inclusive tourists.”1 With the dust from the ballast, he satirizes, “it is much easier to define ourselves as outliers if we can brag about our unpaved, jungle lifestyle on facebook.”2 From the perspective he is pinpointing, dust protects, contains, and isolates.

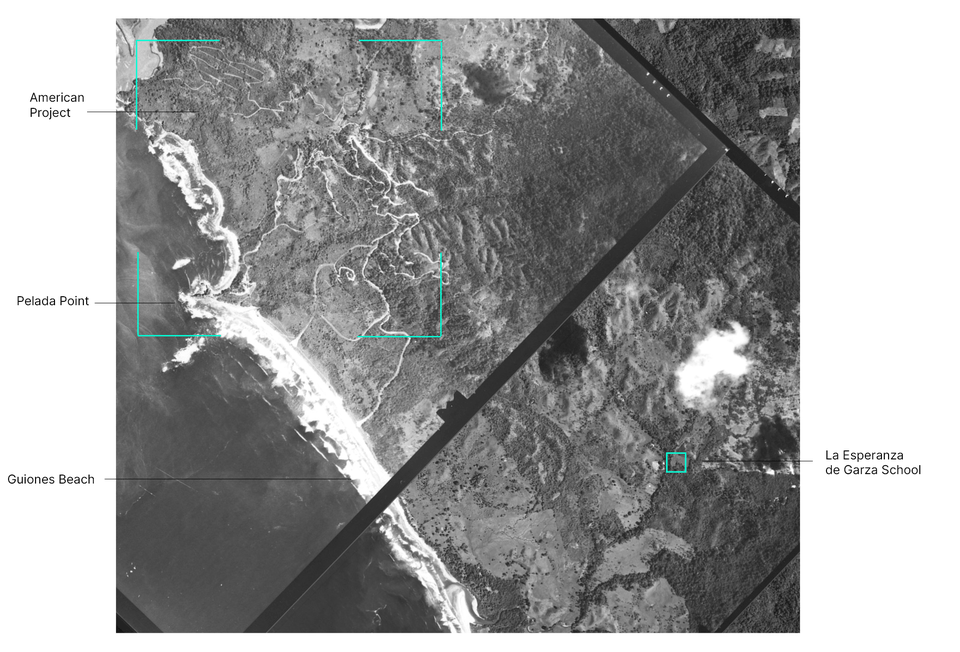

In the early 1970s an American developer bought coastal land in Nosara from Costa Rican landowners in order to build a residential area for the American market. The land had been part of a major territorial concession granted at the end of the nineteenth century by the Costa Rican state to American businessman Minor C. Keith, and to the River Plate Trust Loan and Agency Company, as payment for the construction of a railway connecting the capital to the port of Limón. After the state reclaimed the lands at the beginning of the twentieth century, some properties were transferred to what was then the Institute of Land and Colonization, while others were auctioned or granted to those companies and privileged citizens who could declare them vacant [baldíos]. This triggered a process of displacement and landholding speculation.3 It was within this modality of land privatization that, decades later and after purchase by the American developer, the land was parcelled up, streets were demarcated, and a hotel was built in what came to be known as the “American Project.”

-

Brandon Richardson, “Dust in the Wind,” La Voz de Guanacaste, 29 September 2014, https://vozdeguanacaste.com/en/dust-in-the-wind/. ↩

-

Richardson, “Dust in the Wind.” ↩

-

Guillermo Rodríguez Rodríguez and Andrés Chinchilla Soto, “Ampliación de Informe Expediente 2010-336 RIM,” Informe Técnico Registro Inmobiliario, 2014; José A. Salas Víquez, “La privatización de los baldíos nacionales en Costa Rica durante el siglo XIX: legislación y procedimientos utilizados para su adjudicación,” Revista de Historia 15 (1987): 63-118. ↩

Isolation has been a powerful drive in the recent territorial history of Nosara. As pitched to United States citizens in American newspapers, the fantasy of an isolated “jungle lifestyle” proved to be effective bait to purchasers who bought plots of land without having set foot on them. Some came but did not stay. Although the dirt road was built in the 1940s, in the 1970s and 1980s there were no bridges connecting Nosara, food was transported by canoe, and there were no health services. To reach Nicoya, the closest main town inland, meant crossing the mountains and the river several times by horseback or cart. Electricity arrived in the early 1980s, and a landline telephone network in the early 1990s. This, along with mismanagement by the American developer who promised property titles, electricity, water, and a golf course, paralyzed the residential project, leaving the few who did invest fighting for legal ownership of the land and administration of its resources.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, an airstrip functioning during the summer months allowed tourists to fly to the area. “A single engine plane dropped us on the dirt Nosara airstrip,” recalls an American dentist who, weary of the Vietnam War, was attracted by a country with no army. “We briefly noted the beat-up shack that was a combined air terminal, post office and jail. A bit further on, two cowboys enjoyed beers at a high bar designed so that they could imbibe without dismounting. We loved it. We were hooked.”1 At that time, extensive livestock farming characterized local culture and economy in Costa Rica’s North Pacific zone. This ecology of extensive cattle husbandry and an incipient tourist industry unregulated by the state is cited as the source of the highest deforestation levels in the country in the period from 1987 and 1997.2

From 1995 onwards, American and Canadian real estate developers attracted tourism investment; a trend that accelerated from the start of the 2000s up until the financial crisis of 2008, in tandem with a boom of direct foreign investment concentrated on real state tourism development led by non-residents and an indulgent Costa Rican state.3 During and after this period, the American Project transformed and multiplied.

Unlike the big hotel-chain typology and its concomitant commercial centres and tourist condos that have spread along nearby coastal areas of the Nicoya peninsula, the American Project has remained a tourist beach town tenaciously curated as “small scale, rural and natural.”4 It neighbours the Ostional Wildlife Refuge, a vital nesting site for the olive ridley sea turtle. Still catering today to a market enthralled by the prospect of isolation, developers promote a beachside #junglelife in air-conditioned houses with nearby airport services, located in premium-land gated communities in the surrounding mountains, offering luxury “eco-living,” exclusive physical rejuvenation, emotional healing and yoga retreats, native ceremonies, and surf lessons.5 In this updated mode of isolation, it has been reported that, paradoxically, even unregulated practices like the burning of the forest have been carried out in order to include ocean-views in the design of houses, a valuable asset when it comes to setting rental and property prices.6

Here, unpaved roads figure in the infrastructural aesthetics of a curated nature to be negotiated through private air-conditioned SUVs that generate unbreathable territories in an area that is also prone to forest fires, floods, and water scarcity.7 As a technopolitical agent in motion, SUVs exercise power by constantly reconfiguring barriers and access in their path, suffocating and disorienting those who travel by motorcycle, bicycle, or foot, by day or night.

-

Ed Kornbluh, “Back in the Day-Early Nosara,” La Voz de Guanacaste, 11 January 2015, https://vozdeguanacaste.com/en/back-in-the-day-early-nosara/. The airstrip is identified in the 1957 topographical map. ↩

-

Rodrigo Sierra, Alex Cambronero, and Edwin Vega, “Patrones y factores de cambio de la cobertura forestal natural de Costa Rica, 1987-2013,” Final Report for the Government of Costa Rica under the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF), 2016. ↩

-

María P. Barrantes Reynolds, “’Costa Rica, sin ingredientes artificiales:’ el rol del estado en la expansión del turismo residencial en las zonas costeras,” Anuario de Estudios Centroamericanos 39 (2013): 233-261; Esteban Barboza Núñez, “Funcionamientos, conflictos y contestaciones en la Guanacaste turística y su relación con el discurso colonial,” in Las Playas Imaginadas (Editorial Arlekín, 2020). ↩

-

Julius Leyh, “Resisting Mass Tourism: Local Strategies and Challenges to Maintain Sustainable Development in Nosara, Costa Rica,” (MA Thesis, California State University, Fullerton, 2018), 74. See also: Tara Ruttemberg and Peter Brosius, “Decolonizing Sustainable Surf Tourism,” in The Critical Surf Studies Reader, eds. Snee Zavalza and Sotelo Eastman (Duke University Press, 2017). ↩

-

See, for example, Kalia Modern Eco Living: https://player.vimeo.com/video/458238454. ↩

-

Zoe Dare Hall, “Trouble in Costa Rica’s ecoparadise as homebuyers heat up market,” Financial Times, 9 March 2022, https://www.ft.com/content/fc58e8ee-0f87-4285-91bc-2d46e1052d61. ↩

-

Yarely Díaz Gómez, “Recurrencia, impacto e incidencia de los incendios forestales en la provincia de Guanacaste,” En Torno a la Prevención, June 2020; Alonso Ramírez Cover, “Conflictos socioambientales y recursos hídricos en Guanacaste; una descripción desde el cambio en el estilo de desarrollo (1997-2006),” Anuario de Estudios Centroamericanos 33-34 (2007-2008): 359-385. ↩

Double windscreen view of Route 160, Barco Quebrado, March 2022. © Valeria Guzmán Verri

Through the dispersion of fine dust particles, a trans-corporeal relation between motor vehicle, limestone mountains, ballast surface, wind, and human and more-than-human bodies has been forged. For some, the account of dust functioning as a shield against uncontrolled development and potential crime is an urban myth. And quite rightly so, since such a rendition occludes what the dust actually enacts: that along with an economy of extraction and accumulation, an “economy of suffocation” has been infrastructural to Nosara.1

In addition to the transformation of coastal ecosystems by the geopolitics of tourism for the Global North—a process that has comprised land dispossession, corruption, and territorial exclusion in the Global South—there is the geopolitics of dust and wind that simultaneously suffocates human bodies with bronchitis, bronchopneumonia, and extrinsic bronchial asthma, while imploring others to eliminate toxins by activating the diaphragm and abdomen with yoga breathing techniques such as kapalabhati and ujjayi. A figuration of breathable and unbreathable territories unfolds where the diaphragms and abdomens of some human bodies move in sync with sea breeze, while the bronchial tubes of other human and more-than-human bodies are forced to accommodate the to-and-fro of road-surface particles suspended in the air.

Route 160 is not an exceptional case in Costa Rica: “a large number of localities at the national level could be exposed to problems associated with dust emission on unpaved roads,” indicates the Costa Rican National Laboratory of Materials.2 But laying down asphalt as a solution to dust dispersal, as was the case in 2020 for a ten kilometre portion of the route connecting Garza to Nosara, does not answer broader questions on the mobile territorialization processes that organize relationships between matter, life, and death.

-

Françoise Vergès, “On the Politics of Extraction, Exhaustion and Suffocation,” L’Internationale online, 7 November 2021, https://www.internationaleonline.org/research/politics_of_life_and_death/195_on_the_politics_of_extraction_exhaustion_and_suffocation/. ↩

-

PITRA-LanammeUCR, “Control de polvo en caminos no pavimentados,” Boletín Técnico 9, no.6 (March 2018). ↩

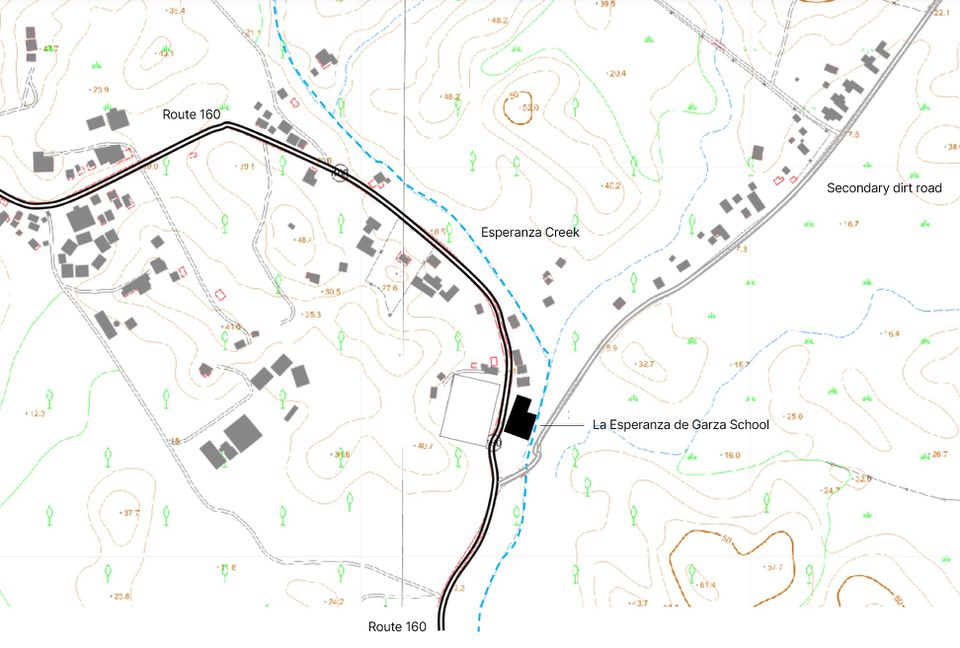

The Esperanza de Garza school is a case in point. A five-classroom building with a canteen and a small playground, the school was originally built with unglazed windows for cross ventilation. With no water service in the dry season from 9am to 3pm, and standing on a plot that is being progressively washed away with each rainy season, today the small school complex is sandwiched between Route 160, a creek, and an unpaved secondary road. With no signposting or speed bumps along this recently paved stretch of the Route, the site is now at greater threat of motor accident.

In the current digital-nomad and “COVID escapee’s” phase,1 asphalt has reinforced the paradoxes of “the smooth and the fast” in Nosara.2 With no sidewalk, cycle path, or signposting budgeted for the paved road, a body walking on Route 160 is today a body at risk of accident. And yet, while new juridical frameworks were swiftly created in Costa Rica to attract remote workers and international service providers earning more than 3000 USD monthly,3 it is still the case that construction regulations which, among others, restrict the use of nightlight in coastal Nosara to allow for the arrival of the olive ridley sea turtle (easily disoriented by artificial light), remain on hold. A deeper gentrification process and a housing crisis is unfolding in Nosara.

Certainly, these relationships between bodies and matter, borders and separations, require the kind of analysis that is no longer fixated merely on static or stable entities. Thinking with Karen Barad’s spacetimemattering and Jerry Zee’s aerosol form, the geopolitics of wind and dust questions political-territorial divisions and the distinctions between land-air and bodies-space.4 An analysis from the trans-corporeal and from continual reconfigurations would then be necessary to refine our relationship with territory.

-

Hall, “Trouble in Costa Rica’s ecoparadise as homebuyers heat up market.” ↩

-

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Jennifer Deger, Alder Keleman Saxena, and Feifei Zhou, eds., “Smooth/Speed,” The Feral Atlas (Stanford University Press, 2021), https://feralatlas.supdigital.org/modes/grid?cd=true&bdtext=isc-smooth-speed. ↩

-

Costa Rican Legislative Assembly, Special Permanent Commission of Tourism, Ley para atraer trabajadores y prestadores remotos de servicios de carácter internacional, File No 22215, 2021. ↩

-

Karen Barad, “No Small Matter: Mushroom Clouds, Ecologies of Nothingness, and Strange Topologies of Spacetimemattering,” in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, Ghosts of the Anthropocene, eds. Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Heather Anne Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt (University of Minnesota Press, 2017); Jerry Zee, Continent in Dust: Experiments In a Chinese Weather System (California University Press, 2021). ↩