On Making Contact

Sierra Komar on Samuel Delany’s liquid urbanity and modes of sociality in the context of the smart city

Somewhere in the American Midwest lies a city whose street signs tend to change unexpectedly. People can be seen walking around with ladders, unscrewing and rearranging metal plates at will, and one might walk into a house on Hayes Street only to find oneself, upon leaving, at the intersection of Ruby Street and Pearl Street. This perpetual instability provoked in one resident the hallucination of all the city’s “walls on pivots controlled by subterranean machines, so that, after he had passed, they might suddenly swing to face another direction.”1 Described, by this same resident, as “a great maze—forever adjustable, therefore unlearnable,” the city is an exercise in disorientation: a place that renders useless all traditional frameworks of location and direction.2 Further east, there is another city, and in this city, a neighbourhood extending roughly the length of 42nd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues. Pornographic theatres proliferate (as do other sex-based enterprises) interspersed with conventional theatres, stage equipment stores, and rehearsal spaces. Drugstores, liquor stores, and diners cater to more sanctioned corporeal needs, providing a place to stop for food, drinks, and other essentials between shows. Whispers of imminent closures and hypothetical office towers grow louder by the day.

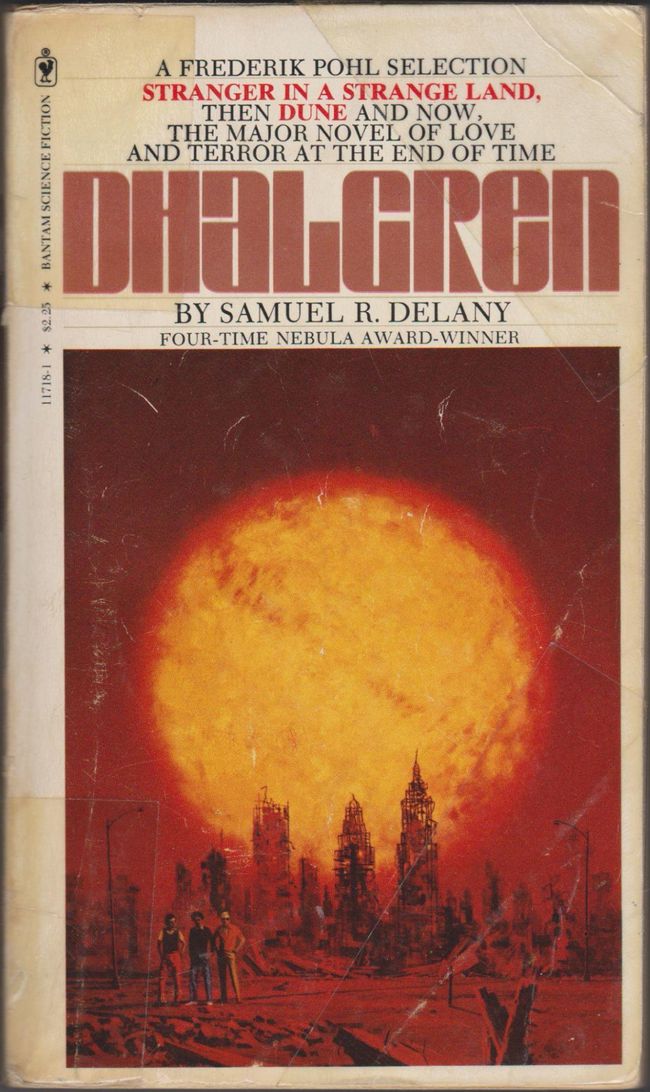

What do these divergent urban landscapes have in common? Each is the setting of a work by Samuel R. Delany: author, literary critic, and professor. Born in 1942 in Harlem, New York, Delany is known primarily for his contributions to the genres of science fiction and fantasy; his sprawling, eight-hundred-page novel Dhalgren, in particular, has become a classic of the genre. A four-time Nebula Award winner, two-time Hugo Award winner, and member of the Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Delany has also authored several works of nonfiction, including the 1999 seminal work of urban and sexuality studies Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. This interdisciplinarity is reflected in the textual cityscapes described above, which, as may be clear, span the science-fictional and the actual. More important than their authorial connection, however, is the vision of urban contact—of being with others in the space of the city—that these textual cities can bring to our increasingly networked present. To wander them is to ask: What forms of connection do we desire from our cities?

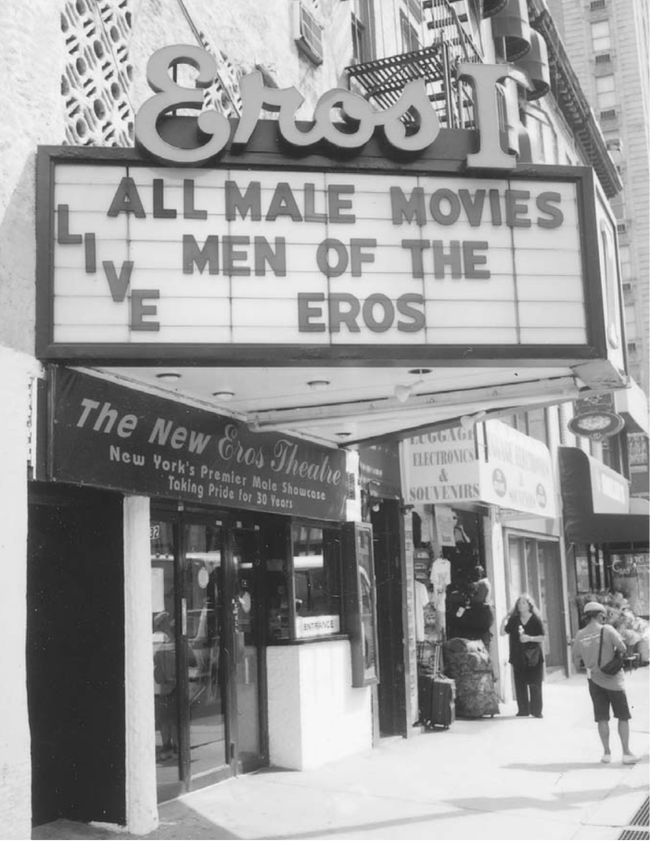

Francis Picabia proclaimed New York “the cubist city, the futurist city,” finding ample inspiration for his paintings in its skyscrapers and their “rush of upward movement.”1 Fritz Lang was similarly moved by the city’s downtown core, citing its luminescent, nocturnal silhouette as the inspiration for his seminal 1927 film Metropolis. New York also looms large in the work of Delany: Times Square Red, Times Square Blue is nothing less than Delany’s textual tribute to the city in which he spent most of his young adult life. And yet, it was not the imposing verticality of New York’s buildings that inspired him, nor the city’s incandescent outline, but rather the assortment of adult theatres, peep shows, and sex shops that populated 42nd Street before the end of the twentieth century. Times Square Red, Times Square Blue is a firsthand, psychogeographic account of Delany’s experiences of this landscape and the sexual enterprises (particularly the porn theatres) that occupied it. It is also an exposition of a theory of urban life as a drama between two competing modes of sociality: “contact” and “networking.”

Contact, for Delany, is that mode of spontaneous interaction that occurs when diverse individuals are brought together by the incidental flows of the city. A term that pays homage to Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities, it describes a form of urban sociality that transpires when people are “thrown together in public spaces through chance and propinquity.”2 Unstructured, unplanned, and unmediated, contact has a special ability to cross lines of both race and class. Its value is affective, certainly, but also literal: not only does it make city life more enjoyable, but its interclass nature means that it often leads to real acts of material distribution, however small. It is for their ability to facilitate contact relations that Delany cherishes such theatres as The Capri, The Venus, The Eros I, and the Adonis, as well as the neighbourhood that surrounds them. The darkness under their projected glow, it turns out, is conducive not just to casual sexual encounters, but to a range of unexpected, informally altruistic exchanges that can only be called contact.

In the book, Delany describes correcting the papers of a fellow audience member in night school, “first in the light of the flickering screen, then, two years later, over the phone.”3 He advises another patron on the process of applying to community college, even going so far as to give the man his phone number should he have any further questions. Meals are purchased for audience members in need, as are clothes, and extra tickets to Broadway shows and concerts at Lincoln Center change hands for nothing. Information and encouragement regarding HIV testing are also shared, resources as valuable as any in the fear and misinformation-ridden terrain of 1980s New York City. In a way specific to contact, all of these exchanges are catalyzed by nearness—by finding yourself next to someone in the theatre or on the street—rather than compelled by any external mandate. They are but an abridged list of the many generosities, large and small, that Delany both observes and participates in over the three decades he frequents the theatres.

-

Elizabeth Lunday, “Francis Picabia’s Chameleonic Style,” Jstor Daily, 15 February 2017, https://daily.jstor.org/francis-picabias-chameleonic-style/. ↩

-

Samuel R. Delany, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 128. Delany borrows the term “contact” from a chapter of Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities entitled “The uses of sidewalks: contact,” in which Jacobs argues that the casual, informal “contact” with others facilitated by the public space of the sidewalk (and adjacent spaces such as the stoop) is an asset to a neighbourhood’s residents and their safety. Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (New York: Random House, 1961). ↩

-

Delany, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, 90. ↩

Why porn theatres in particular? Though the objective spatial conditions of contact are impossible to formalize, it tends to thrive in those landscapes that facilitate the dissolution of social stratification and facilitate unpredictable, face-to-face interactions between different subjects. The spaces of casual sex (porn theatres, cruising parks) accomplish this, as does the non-sexual space of a normal, heterogeneous neighbourhood the structural variety of which attracts a wide range of individuals. Put differently: landscapes of contact are those more fluid arrangements of urban space that facilitate, for their residents, unexpected configurations of presence with one another. The ultimate form of this comes in the shifting streets of one of Delany’s fictional cityscapes: Bellona.

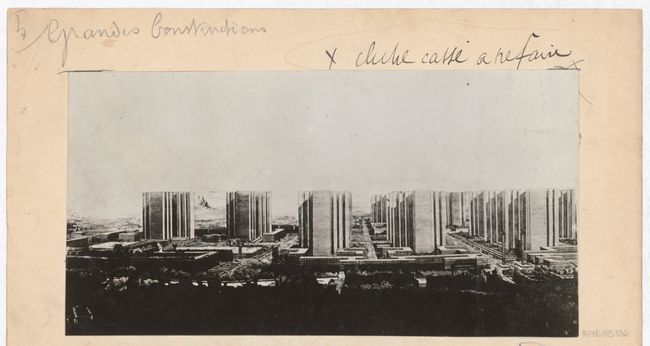

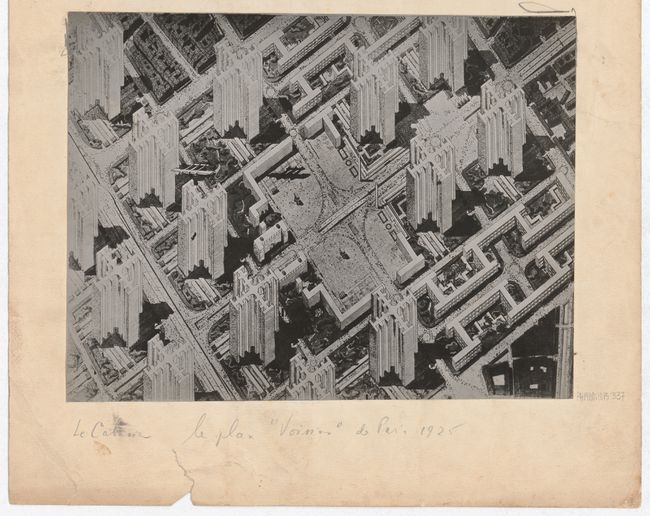

The setting of Delany’s 1975 novel Dhalgren, Bellona, is a winding, impossibly Daedalian metropolis in the wake of an unspecified disaster. This disaster caused many of its original residents to flee, and there is no consensus amongst those that remain as to whether what took place was a meteor, a bomb, or a riot. Fires rage constantly, veiling the streets under a near-constant cover of smoke, and on certain clear nights, one can observe not one but two moons in the sky. Then, of course, there is the issue of the city’s restless, ever-moving streets. In a surrealist inversion of the standardized, symmetrical grid of modernist urban planning (the city projects of Le Corbusier being the archetypal example), Bellona’s topography is fluid, irrational and prone to unpredictable movements and displacements. Though sometimes related to observable street sign tampering, this fluidity extends beyond these antics: somehow, the streets just change. As one resident observes: “You go down new streets, you see houses you never saw before, pass places you didn’t know were there. Everything changes.” “Sometimes” another resident chimes in, “it changes even if you go the same way.”1

-

Delany, Dhalgren, 355. ↩

An exaggerated manifestation of the liquid landscape of a pre-1995 Times Square and its porn theatres, Bellona’s chronically slippery grid has one important effect: it makes it exceedingly difficult to control exactly what—and who—you will experience as you move through the city. Buoyed by the shifting streets, residents are constantly brushing up against each other in ways that, although occasionally antagonistic or anxiety-provoking, are for the most part both pleasant and advantageous. Bellona, in other words, is a contact landscape taken to the extreme: a fictionalized exploration of the dynamics that Delany would later theorize in the nonfictional context of Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. It, too, is a city saturated with contact and the forms of proximity-driven exchange it makes possible. Though Dhalgren comprises over eight hundred pages of urban wanderings, it would be difficult to name more than a handful of moments where the novel’s protagonist, Kid, has to actively seek something out, whether this something be meals, weapons, or companionship. Although in no small part related to his inability to do so (an inability related to the increasingly hallucinatory mental state in which he finds himself over the course of the novel), this lack of effort is also reflective of the ease and frequency with which contact takes place in the city’s fluid streets. Food and shelter are offered readily—Kid finds both only moments after entering the city and talking with someone on the sidewalk. He receives a job (or, at least, what passes for such in Bellona) after another chance meeting on the sidewalk, and a publishing deal through a similar chance meeting at a bar. Indeed, it could only be due to the surprising preponderance of contact in the Bellona that the city, despite its post-apocalyptic overtones, is still described by those that live there as “an essentially hospitable place.”1

With Dhalgren’s fictional book deal, however, we are suddenly catapulted back to the existing city of New York, and to the tension that exists between contact and another mode of urban sociality: that which Delany calls “networking.” Though he is careful not to ontologize the opposition between the two terms, networking emerges, at least broadly, as the opposite of contact. Whereas contact flourishes in fluid, flexible landscapes, networking takes place within the stable boundaries of institutional space. Whereas contact is an interclass phenomenon, networking is intra-class and proliferates within uniform, homogeneous groups. Finally, whereas the outcomes of contact are fundamentally unpredictable, and often include forms of material exchange, networking tends to be self-replicating: it produces more of the same, and rarely results in acts of material exchange. This is because of the similar economic and social status of its participants, as Delany’s favorite example of the networking landscape, the writer’s conference, demonstrates. Though the writer’s conference plays host to an overwhelming number of desires related to book deals and other acts of “writerly generosity,” it is also the space where these events are the least likely to occur. This is simply because, Delany argues, the occupants of such spaces tend to be similar: everyone is looking for the same thing.

-

Delany, Dhalgren, 416. ↩

Crucially, and most dangerously, networking is often proposed—by city officials, by real-estate developers, by law-enforcement agencies—as a safer, less messy substitute for contact. This proposal is one that both exploits and produces collective anxieties surrounding encounters with a difference—one that plays subconsciously off contact’s etymological roots as a word that encompasses both touch and the fear of contamination. It is the acceptance of this false proposal, Delany suggests, that ultimately underwrote the cannibalization of Times Square by the forces of redevelopment, forces whose effect is now referred to colloquially as the “Disneyfication” of Times Square. In the end, it was networking that triumphed: in the 1995 zoning ordinance that effectively illegalized all sex-related establishments in the area; in the identical restaurants, hotels, and retail outlets that moved in to replace them; in the president of the Times Square Business Improvement District’s famous proclamation that any lamenting the former neighbourhood would be equivalent to “romanticizing the gutter.”1 Recently announced plans to “revolutionize Times Square with a brand new digitally transformed experience,” however, have lent a new and unintended dimension to networking’s victory on 42nd Street.2

Spearheaded by semi-conductor and wireless technology manufacturer Qualcomm—whose previous “smart” developments have included both marine bases and naval fleet carriers—the “Smart Times Square Experience,” or STSX, project aims to bring “state of the art connectivity infrastructure” to the area, more specifically to the fifty thousand-square-foot hotel and performance venue currently in development at 1658 Broadway. This connectivity infrastructure, consisting of 5G and Wifi6 networks, will provide the basis for “immersive indoor and outdoor experiences” around the development, as well as a “central control and command system.” Far from unique, this project joins a host of other initiatives that fall under the banner of the “smart city”: an urban typology that emphasizes the widespread use of information and communications technologies as the key to city life. A term that refers both to entire cities as well as to more limited developments like the STSX project, it also encompasses citizen engagement applications such as BOS: 311, FixMyStreet, and Commonwealth Connect, which allow citizens to “connect” with the city individually and report potholes, waste issues, and other infrastructural problems.

-

Bruce Weber, “In Times Square, Keepers of the Glitz;3 Women Overseeing Block’s Rebirth Promise to Return Its Splendor,” New York Times, 25 June 1996. ↩

-

“Qualcomm Revolutionizes Times Square with Immersive, State-of-the-Art Visitor Experiences,” Qualcomm, 16 November 2021, https://www.qualcomm.com/news/releases/2021/11/16/qualcomm-revolutionizes-times-square-immersive-state-art-visitor/. ↩

Though the technological connotation of networking is absent from Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, Delany’s rendering of networking proves remarkably descriptive of many of these projects. This is not simply because of their literal reliance on networked technologies, but because of the homogeneity that lies submerged under their expansive language of connectivity. The “connectivity infrastructure” associated with the STSX project, for example, caters only to circumscribed, pre-imagined groups of subjects: the family, the tourist, the entertainment lover. It is an infrastructure that is already stratified, one whose definitively immaterial “experiences” and “connections” will circulate only among similar individuals. A similar pattern has been observed even in more superficially democratic smart city projects such as BOS:311 and Commonwealth Connect. Though designed for their respective communities at large, these applications tend to receive input only from a particular class of people: “well-educated, technologically literate participants in the digital public sphere.”1 Just as contact finds its outsized expression in the mercurial landscape of Bellona, networking too, seems to find its ultimate expression in the smart city: a landscape that, though equally as speculative, is perhaps less “hospitable.”

-

Paolo Cardullo and Rob Kitchin, “Being a ‘Citizen’ in the Smart City: Up and down the Scaffold of Smart Citizen Participation in Dublin, Ireland,” GeoJournal 84, no. 1 (December 2018): 8. ↩

To visit Delany’s textual cities is thus not only to experience a more liquid vision of urbanity and the forms of contact it makes possible. Rather, it is to also gain a new perspective on the temptations—and limitations—of the forms of networked connectivity that we are increasingly being offered by our cities. These limitations are captured powerfully by one moment that occurs in both New York and Bellona, echoing across the space that separates urban fact and urban fiction. There is a passage, in both Dhalgren and Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, that describes an unexpected celestial spectacle bursting into the sky above the city. A second moon in the case of Bellona, the visible streak of the comet Hale-Bopp in the case of New York, these events prompt explosions of interaction on the streets between friends and neighbours, but also between complete strangers, and passersby. As Delany writes of his interactions on the night in question, “I have seen none of the people involved in them again.”1 These events themselves are extraordinary, without doubt, but they are made even more so by how they can be remarked upon, pointed out to, and experienced with others. They beg the question: in a city without contact, what point is there in looking to the skies?

-

Delany, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, 183. ↩