Hong Kong / the opening of space and fixed-frame film

Sony Devabhaktuni considers the stillmoving image

As Hong Kong continues through a period in which the future is enforced as a stable and enclosed realm of action, fixed-frame film, as a practice of the city, attends to the contingent present. It calls forth an attunement toward the uncertainty of becoming: where doubt and questioning are necessary qualities of a future still held close as potential.

Wednesday, 14 March 2018, start time 18:30, from Bowen Trail

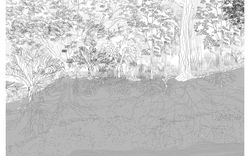

Jockey Club Race Track on a Wednesday without races. Light from Times Square empties from within the huddle of buildings in the middle distance. Two televisions in adjacent flats are tuned to the same evening show. Hawks circle on currents, scanning into the trees. Traffic from South Island slows along the overpass that divides Wan Chai and Causeway Bay. On Bowen Trail, runners stride heavily. Their breathing and the conversations of passersby become distinct, then recede against the hiss-whir of insects.

Film moves images through time to figure space. In films of cities, this moving of images can function as a series of quick cuts or else at speeds that create a sinuous continuity. Both ways of figuring the city–as staccato or never-ceasing–obscure the image itself, allowing the operative sensibility to take hold. I am thinking, for example, of Godfrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance (1982) or of Jessica Kingdon’s more recent observations of contemporary China in Ascension (2021). These films solicit a way of looking that depend less on an attuned gaze, than on an awestruckedness that renders the image itself undemanding.

Counter to the interweaving those works enact, the fixed-frame film proposes a singular, stable opening into territory. Nearly photographic in its immobility, the fixed-frame’s stable image calls forth an attention to surface: a feeling for the changes that take place there. The accumulation of these changes and the image’s extension through time opens onto a becoming.

As the media scholar Catherine Fowler has noted, the fixed-frame returns to the origins of film when technicians working with bulky cameras shot “actualities” of ordinary people doing everyday things.1 The capacity to transcribe the world 24/7 was at first sufficiently stunning. But soon, day-to-day scenes were overcome by contingency: not of the terrible happening, but instead of nothing happening at all. To fill this emptiness, filmmakers turned to narrative. The auteur ensured that something taking place precluded boredom’s arrival. This engendered a habitual mode of viewing in which event and anticipation marked the passage of time.

The fixed-frame film rewinds this contemporary expectation by offering an “actuality” in which the contingent is a flattened plane of nothing happening at all. We see this, for example, in Andy Warhol’s famous eight-hour take of the Empire State Building. Arthur Danto described Empire (1964) as a revelation of cinema—a Socratic coming to essences—that demonstrates that little in a moving picture needs to move for it to be a film.2 What did move, however, was the strip of celluloid, with all of its material imperfections, watery like retinal afterimages.3

-

Catherine Fowler, “Obscurity and Stillness: Potentiality in the Moving Image,” Art Journal 72, no. 1 (2013): 65. ↩

-

Arthur C. Danto, “Moving Images,” in Andy Warhol (New Haven; London: Yale University Press), 79. ↩

-

Nam June Paik’s Zen for Film expressed this material aspect of film through the projection of “clear film, accumulating in time dust and scratches.” See Allen S. Weiss, “Some Notes on Conjuring Away Art: Radical Disruptions of Image and Text in Avant-Garde Film,” L’Esprit Créateur 38, no. 4 (1998): 88. ↩

In contemporary cinema, the moving matter of film has been replaced by digital procedures that inscribe a new relation between what is moving on the screen and within the technology of projection. As Jon Inge Faldalen points out, the processing of digital data codes stillness and movement separately. This is not the case in film or video, where the unavoidable advancement of the reel supersedes the image’s stability. With digital imaging, while an altered square of light requires the calculation of a new data set, a pixel that does not change from one instant to another processes no new information. This is manifest in the screensaver, designed to prevent the burning of unchanging pixels onto the screen. Faldalen points out that when a shadow moves across a rock, only the edges, in fact, change; the dark centres remain constant until they too are overcome by light.1 In the digitally projected screen, the unaltered pixel is that shadowed, unchanging middle ground.

-

Jon Inge Faldalen, “Still Einstellung: Stillmoving Imagenesis,” Discourse 35, no. 2 (2014): 235. ↩

Wednesday, 14 April 2021, start time 17:02, from Lok Ma Chau

Shenzhen beyond the Sham Chun River. To the south of this frontier are fallow agricultural lands. To the north, towers in a seemingly single file along the horizon. The heaving of lorry engines and the chirping of reversing trucks signal earthworks. The early evening light hardly changes; shifts in its silver inflection sharpen angular profiles and open views into the distance. From the base of the darkening, half-charred hillside, a wavering of smoke trails obliquely from the ground.

Larry Gottheim shot Fog Line (1970) outside Binghamton, New York. The film opens with a screen of even grey marked with horizontal lines and a dark splotch. This abstraction shifts and recedes to bring forth a bucolic landscape; the green of the hillside imposes itself like a chemical reaction in the atmosphere. The film scholar Scott MacDonald writes: “There are no dramatic events; there is no punch line… What ‘events’ there are are subtle, and for most first-time viewers, invisible…”1 Close attention seems to reveal two “ghost horses” underneath trees in the middle distance, their figures providing scale to what was at first unmeasurable.2 Where Warhol’s Empire maintains a cool distance, Fog Line invites the viewer to register change and gauge movement against stillness: those things that appear or are revealed against what has always been there.

-

Scott MacDonald, “Ten (Alternative) Films and Videos on American Nature,” Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and Environment 6, no. 1 (1999): 3. ↩

-

Larry Gottheim, “Fog Line (1970),” Larry Gottheim Films, https://www.larrygottheimfilms.com/descriptions. ↩

Of Sharon Lockhart’s Double Tide (2009)–which shares Fog Line’s aesthetic of movement and stillness–MacDonald asks: “How long and how carefully can you look?” proposing that, “This is a challenge that seems ever more radical in our world of ever-accelerating distraction.” 1 Lockhart’s ninety-nine-minute, two channel installation tracks the movement of a clammer as she takes advantage of the coincidence of low tides twice within the span of a single day–at dusk and dawn. As the clammer pursues her task, she recedes into the horizon but stays within the frame, suggesting a choreographed complicity with the filmmaker. As in Fog Line, stillness and movement depend on each other such that becoming unfolds as a contingent present coincident with viewing.

-

Scott MacDonald, “Cine-Surveillance: 3 Avant-Docs Interviews with Amie Siegel, Sharon Lockhart, Jane Gillooly,” Film Quarterly 66, no. 4 (2013): 28. ↩

MacDonald has described fixed-frame films as a “slow-cinema,” foregrounding their relation to time. In his writing on shadows, Faldalen speaks of them as stillmoving–a category that depends on the tripled meaning of still: “as a concept combining its adjectival spatial meaning, not moving, and its adverbial temporal meaning, continuing, as well as its affective agency to calm and quiet.”1 Faldalen suggests as well that the in-betweenness that characterizes the fixed-frame’s relationship to photography qualifies it as another kind of stillmoving. This stillness is about fixing a space for the slowness of time to make itself available. The tripled meaning of “still” threads through the ambiguity of a cinema that is at a threshold between activity and stasis, and where this liminal state functions to open up a different possibility of being “calm and quiet.”

The stillness of fixed-frame films constructs a specific relation to remembering and forgetting that differs from many experiences of cinema. Its continuity is such that our recollection of what passed before is latent. We are sensible to the past through its immanence within the present image. Yet, like memory itself, the certainty of how things were is clouded by what is there now; the quality of immanence registers as an uncertainty that makes any kind of stable reading or knowing difficult. This uncertainty is a doubt about the nature of becoming and demands a double action of scrutiny and openness. Scrutiny is directed not toward any pre-determined point within the frame, but rather to there where the viewer chooses to direct her gaze. Viewing or watching becomes the dispersion of vision across the horizontal plane of the frame: an evenly stretched attention and alertness that feels for pricks across the surface. Knowledge is at once invited and frustrated within the image’s constantly but almost imperceptibly changing field.

Fowler argues that this process of frustrated knowledge acts as an incitation toward visual attentiveness. The fixed-frame film moves away from actuality to what she calls a “potentiality.” Potentiality is founded not in the event, but rather in an attentive, undirected, and even looking that renders the time and space potent.2

Potentiality resonates with readings of the city that foreground the urban as a set of open relations rather than a mise-en-scène. Brian Massumi, writing about his collaboration with the urban media artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, describes the city as a “space now defined as much as an overcharge of potential paths of human encounter as by its geometrical and geographical properties.”3 This space, these potential paths, transform the city from “site” to “sets of relations,” such that interventions are no longer “site specific but relationship-specific.”4 The traject-ing intersections of these relations, describing the paths of human and non-human actors, of architectures as well as air, rocks, and animals, comprise “a surplus of undefined potential.”5 Where city as site is a backdrop against which things take place, the city as relations allows a different kind of perception because “the relation always arrives … in advance of its next sequential unfolding.”6 This continuous development of the city’s relational structure means that perception must remain open and attuned. The visual becomes one of many thresholds to the city’s potentiality.

Potentiality figures the territory of the city not as an event, but as a relation-specific becoming. The city emerges as an amalgamation of trajectories–of matter, lives, and practices that comprise space. This is an imagination that resists the figuring of space as inert, contained, or neutral, instead casting it as teeming and in movement: a constant circulation of trajectories from near and far that produce possibilities of reconfiguration. The geographer Doreen Massey argues that such a spatial reconceptualization–one that puts forward imaginations of space as becoming–is necessary to keep the future open. This openness is, in turn, the basis for the political.7

-

Faldalen, “Still Einstellung,” 235. ↩

-

Catherine Fowler, “Obscurity and Stillness: Potentiality in the Moving Image,” Art Journal 72, no. 1 (2013): 65. ↩

-

Brian Massumi, “Urban Appointment: The Possible Rendez-Vous With the City,” in Making Art of Databases, ed. Jake Brouwer and Arjen Mulder (Rotterdam: V2 Organisatie/Dutch Architecture Institute, 2003), 2. ↩

-

Massumi, “Urban Appointment,” 7–8. ↩

-

Massumi, “Urban Appointment,” 9. ↩

-

Massumi, “Urban Appointment,” 7–8. ↩

-

Doreen B. Massey, For Space (London: Sage, 2005). ↩

Wednesday, 10 February 2021, start time 16:12, from Cecil’s Ride

Across the harbour, squat buildings along a sliver of land. They are incommensurable with the towers and quarried hillsides that rise behind them. The Cross-Harbour Tunnel empties into an expanse of concrete, marked by a wall of tollbooths. Tugs, ships, and sailboats trace paths that would be well-worn if on land. A ferry service makes the return trip from Kwun Tong to Wan Chai at the edge of the frame. Peaks emerge in the near and far distance. Some hills are as tall as towers. They fade and reveal themselves like darkened shadows as the sun itself appears.

The author is grateful to Ng Ka Lung Kal and Fan Xinkai for their assistance with shooting the films in the Hills / Towers series.