Projecting the Landscape

Alec White Reflects on the Role of Belvederes in the Conception of Territory

I wrote this article in winter 2022 after visiting three belvederes erected at mining sites in the cities of Thetford Mines, Asbestos, and Malartic, in Quebec. Such seeminly innocuous architectural structures are quite ubiquitous. After all, who has never, on a stroll in a natural setting or a park, found themselves on a path leading to a belvedere that offers a panoramic view of the landscape? The belvedere—which first appeared in the sixteenth century during the Italian Renaissance and was called bel vedere, meaning “beautiful view”1—acts as a guide for the body and the eye. From a distance, it beckons: “Here is a landscape worthy of being seen; come and look.” Its architectural plan orients our movements and frames our gaze toward a landscape that is, presumably, pleasant. Thus, it is an instrument for conceiving landscapes, both physically and figuratively. The belvederes that interest me here present visitors with landscapes that are ambiguous, litigious, far from an idyllique natural setting or a breathtaking urban panorama. Rather, they look out over sites where industrial activity has drastically altered nature. It is the distortion provoked by the presence of belvederes in such places that makes me want to consider these structures in the context of figuring territory.

-

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Belvedere,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 27 May 1999, https://www.britannica.com/art/belvedere. ↩

Thetford Mines

With a population of a little over twenty-five thousand, Thetford Mines is historically linked to asbestos mining. The towering black mountains of mining waste around the city are a reminder of this fact. Two belvederes built on the municipality’s land look out over disused mine shafts. The first, situated near the Lac d’Amiante mine, was built in 1991 by Tourisme Amiante and was long a major tourist attraction for the region.1 In 2010, however, the collapse of Route 112 running alongside the mine forced the closure of the popular belvedere.2 Tourisme Région de Thetford quickly decided to erect a belvedere beside the smaller British-Canadian mine. Newer and smaller than the one at Lac d’Amiante, it nevertheless annually draws a large number of visitors, who come to view the old mine shaft, now filled with exotically coloured turquoise water.3

-

Tourisme Amiante, Dossier de candidature pour Les grands prix du tourisme québécois (Thetford Mines, 1993). Centre d’archives de la région de Thetford. ↩

-

“La région de Thetford Mines réclame sa route 112,” Le Soleil, 30 October 2012, https://www.lesoleil.com/2012/10/30/la-region-de-thetford-mines-reclame-sa-route-112-82ec8d6c179928edee5d39b4e6fa2845. ↩

-

Claudia Fortier, “Investissement de 40 000 $ au belvédère de la mine BC,” Courrier Frontenac, 18 October 2021, http://www.courrierfrontenac.qc.ca/actualite/investissement-de-40-000-au-belvedere-de-la-mine-bc-thetford/. ↩

The belvederes in Thetford Mines—and in many other places—undeniably fulfil a tourism-related economic function. Historically created by and for the asbestos industry, the local communities in the region are the heirs to the industry’s vestiges.1 The mines closed for good in 2011, and the tourism industry took consolation by recycling, for meagre profit, these lunar landscapes composed of almost 800 million tonnes of tailings.2 Is this a case of ruin tourism? Perhaps, but rather than the remains of an ancient city dating from 2500 BCE, these ruins are less than a century old. In their essay “Written Residues From a Trip to Asbestos Country,” Dalie Giroux and Amélie-Anne Mailhot discuss these vestiges of the mining industry through the lens of Robert Smithson’s concept of the anti-monument: “It is an unconscious monument, which would be an effect rather than a cause: sandpits and other quarries, huge abandoned buildings, other gigantic infrastructure elements, and industrial residue with no purpose—pure negativity.”3 For the tourism industry, the belvedere acts as a means of production. And what does it produce? Landscapes. In his text L’arrière-paysage: des origines technologiques du paysage, Michael Jakob explains that the idea of the landscape as an autonomous aesthetic object arises from different technologies related to representation and gaze, most of which were invented during the Italian Renaissance: measurement instruments, the modern window, the frame, the border, and the loggia, among others. Therefore, behind the ultimate representation of the landscape are interwoven the different technologies that make it possible.4 The belvedere itself, which also appeared during the same era and in various forms—including that of the loggia, as Jakob mentions5—is thus an architectural apparatus that combines a set of technologies, making it a “landscape machine.”6

-

“La région de l’amiante presse Québec de planifier la transition,” Le Devoir, 14 August 2013, https://www.ledevoir.com/politique/quebec/385090/la-region-de-l-amiante-presse-quebec-de-planifier-la-transition. ↩

-

Alexandre Touchette, “Le lobby de l’amiante encore très actif au Québec,” Radio-Canada, https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1130520/lobby-amiante-quebec-chrysotile-mines-residus; “Plus de 400 milliards $ de résidus miniers,” Courrier Frontenac, 6 December 2019, https://www.courrierfrontenac.qc.ca/actualite/plus-de-400-milliards-de-residus-miniers/. ↩

-

Dalie Giroux and Amélie-Anne Mailhot, “Written Residues from a Trip to Asbestos Country,” in Going To, Making Do, Passing Just the Same, ed. Edith Brunette and François Lemieux (Montréal: Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery and Concordia University, 2021), 31. Free translation. Published to accompany an exhibition of the same title, organized by and presented at the Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen Gallery from 11 February to 27 March 2021. ↩

-

Michael Jakob, L’arrière-paysage; des origines technologiques du paysage (Paris: Éditions B2, 2019). ↩

-

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Belvedere.” ↩

-

Jakob, L’arrière-paysage, 68. Free translation. ↩

In this sense, the example of the belvedere at the Lac d’Amiante mine in Thetford Mines is eloquent. It comprises a raised platform, framed bay windows, and a system of fixed binoculars—a set of elements that produces landscapes to which the tourism industry will attract visitors. Today, although the mine shafts have been deserted by the mining industry and by biodiversity, it is still possible to see carrion-eating turkey vultures flying around above them.1 With its belvederes and in its own fashion, the local tourism industry perceives these cumbersome carcasses of the mining era as a potential source of profit, as slim as it might be.

-

Morgan Lowrie, “Cinq ans après la fermeture de la mine Jeffrey, Asbestos tente de renaître,” Le Devoir, 25 August 2016, https://www.ledevoir.com/non-classe/478516/regions-cinq-ans-apres-la-fermeture-de-la-mine-jeffrey-asbestos-tente-de-renaitre. ↩

Asbestos

Affixed to the industrial belvedere in the city of Asbestos—now renamed Val-des-Sources—are a plethora of references to the city’s mining past. This apparatus, through which we are invited to move, functions as a playful and aesthetic environment, a place to spend a little time, but what we are prompted to feel and perceive is fundamentally self-serving.1 On the path by which we reach the platform, we come upon various relics and information panels related to the mining industry. On some displays, the elegy to the “magical mineral” makes it plain that Asbestos is sleeping on “buried treasure.”2 The panel on the platform’s guardrail describes the chronology of the site that we are looking at. The history of the vista before us began in 1880 and is divided into different “eras” during which advances in technology and ways of exploiting the land dictated how the “white gold” was extracted. There is no mention of the precolonial occupation of the site by the Abenakis long before 1880, the social conflicts that marked the history of the mine—such as the violent asbestos strike of 1949—or the highly carcinogenic properties of asbestos, the wonderful ore.3 This narrative influences the representation of the landscape and its history to which belvedere visitors are exposed.

-

Jakob, L’arrière-paysage, 68. ↩

-

On-site information panels. Free translation. ↩

-

Jean-Marie Dubois and Nathan Baker, “Val-des-Sources (Asbestos),” Canadian Encyclopedia (13 September 2009, last edited 6 January 2021), https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/asbestos-que. ↩

So, this belvedere may appropriately be considered an apparatus, but in a broader sense than simply a grouping of technologies responding to an economic function. Michel Foucault describes the apparatus (or dispositif) as being composed of “a thoroughly heterogeneous set consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral, and philanthropic propositions.”1 It is “the network that can be established between these elements” and that possesses “a dominant strategic function” of “manipulation of relations of forces […] inscribed into a play of power, but it is also always linked to certain limits of knowledge that arise from it and, to an equal degree, condition it.”2 Thus, through its arrangement of the landscape, its historical and geological statements that frame the visit to the site, and the value judgment that it suggests by highlighting this landscape, the belvedere is both based on and produces knowledge-power relations. It suggests ways of being, perceiving, and feeling. In general, it forms subjects that support a political order. What remains to be answered is which order this is.

Malartic

The belvedere at the mine in Malartic is situated at the top of the Mur vert [green wall], an artificial embankment about fifteen metres high that separates the small city where I grew up from the Canadian Malartic mine, the largest open-pit gold mine in the country. The landscape presented by the belvedere is relatively new. Just over ten years ago, what is today a huge industrial site active twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, year-round, was a residential neighbourhood with more than two hundred buildings, including three schools, a long-term-care residential centre, and the apartment that my family lived in until the early 2000s.

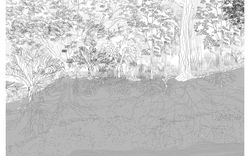

In 2006, when Osisko Mining Corporation—today Canadian Malartic—launched its project, the residents of the neighbourhood impinging on the coveted ore deposit were offered the choice between expropriation with compensation and expropriation without compensation. Because the provisions of Québec’s Mining Act take precedence over property rights, refusing to hand one’s property over to the mining company was simply not an option.1 With or without the consent of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities impacted, the project would go ahead. Although some are happy with it, the landscape today celebrated by the belvedere made others very unhappy. Another subtext of this gargantuan landscape is the continuation of a colonial project of territorial dispossession inflicted over the decades upon the Anishinabeg Algonquin Nation. It is the result of expropriations—sometimes enforced by the police—of settlers and of a divided local community.2 It is also an environmental plundering that is perpetuated to this day—Canadian Malartic is one of the worst environmental offenders of the last ten years and the twenty-second-highest emitter of carbon dioxide in Québec.3 And what if one landscape were hiding another?

-

Laura Handal Caravantes, “3. Mines; L’histoire d’une triple dépossession,” in Dépossession, ed. Simon Tremblay-Pepin (Montréal: Lux, 2015), 145. ↩

-

“Le dernier résistant à la minière Osisko à Malartic a été sorti par la force de sa résidence, lundi matin,” La Presse, 9 August 2010, https://www.lapresse.ca/actualites/regional/201008/09/01-4305078-le-resistant-de-malarctic-est-sorti-de-force-de-chez-lui.php. ↩

-

Annabelle Blais and Charles Mathieu, “Pollueurs en série au Québec: la mine d’or de Malartic est le plus grand récidiviste,” Le Journal de Montréal, 19 April 2022, https://www.journaldemontreal.com/2022/09/01/la-mine-dor-de-malartic-est-le-plus-grand-recidiviste; “Le Top 100 des pollueurs,” Le Journal de Montréal, https://www.journaldemontreal.com/le-top-100-des-pollueurs. ↩

In his book Philosophie de l’architecture, Ludger Schwarte invites us to consider the concept of landscape in relation to the European art of gardens in the early modern period, when gardens were considered a weapon against political and social disorder. Like portraits of the king, gardens expressed the social rank and political ambition of their owners. To fulfil this function, the garden had to appear inaccessible and private, so as to purge all external elements seen as unworthy, and the enclosure had to give “the impression of necessity and order, following constraints of logic and rationality even where it appeared playful and picturesque.”1 Designed by the mining company itself in 2011–2012, the belvedere at the Malartic mine is part of a sub-project, the construction of the Parc du quartier sud, included in the subsoil-mining megaproject.2 From the height of the belvedere, the landscape on view—a sort of garden made by capital—is a scene cleared of all disturbing elements that could impede the company’s aims: living spaces, public roads, social struggles, citizen dissidence, property rights, biodiversity, environmental standards, decent fiscal frameworks, or Indigenous land claims. It’s the stage for a play endlessly rehearsed, “in which the well-off classes express, through what is on view, the possession of the land and the social relations that play out there.” It’s a site of spectacle totally emptied “after the tragedy of the social processes of appropriation has taken place there, unilaterally.”3 From on high, in the belvedere that acts simultaneously as projector and as seat for the spectator, it is this very partial representation of the territory that is on display, and no doubt it is a beautiful view for those who don’t get to see what is backstage.