Animal Passages

Phoebe Springstubb on how the migration of fur seals defined the inside and outside of empire

“[The fur seal] gave a terrifying roar and presented a formidable front … He was a magnificent picture of rage, courage and beauty, with his splendid coat that would make a rug 7 ft. square at least!”1

-

Letter of Captain Charles Abbey to his wife from St. Paul Island, 2 July 1886 (underlined in the original), Abbey Family Papers, folder 1, Arctic and Polar Regions Collections and Archive, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. ↩

Breeding in summer on the rocky beaches of the Pribilof Islands, off the coast of mainland Alaska, northern fur seals (Callorhinus ursinus) are pelagic from late fall through spring. They migrate across expanses of the North Pacific, the Sea of Okhotsk, and the Bering Sea, following the eddies of ocean currents and gyres. Male seals winter in northern waters, while females and juveniles migrate south, off the coasts of California and Japan’s Honshu Island, over distances spanning thousands of kilometers. Though researchers have reconstructed fragments of the seals’ freewheeling aquatic world, much remains unknown about their travel and role in aqueous ecosystems.1 In the second half of the nineteenth century, during the height of the commercial fur trade, the black box of fur seal migration was a resource and instrument of territorial enclosure for United States empire. Tracking the fur seal became a spatial and legal means of defining empire’s reach.

-

Tonya Zeppelin et al., “Migratory Strategies of Juvenile Northern Fur Seals (Callorhinus ursinus): Bridging the Gap Between Pups and Adults,” Scientific Reports 9 (2019). Rolf R. Ream et al., “Oceanographic Features Related to Northern Fur Seal Migratory Movements,” Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 52, no. 5–6 (March 2005): 823–843. Researchers have, for instance, used isotopic analyses of the keratin whiskers of different fur seal species to study their foraging and feeding ranges. ↩

The Pribilofs, where the seals’ rookeries are located, had been purchased from Imperial Russia in 1867 as part of the unceded territory of Alaska, the US’ first noncontiguous possession.1 Along with Alaska’s land, the US government took hold of colonial sealing infrastructure Russia had established, along with the labour and knowledge of the Indigenous peoples for whom the region was a homeland and who had been conscripted, during a century of Russian occupation, to manage seal harvests. The US Treasury Department granted a lucrative sealing monopoly to a single company, used its agents to enforce that monopoly, and introduced a taxation policy benefiting government coffers.2 What could not be controlled, however, was the stretch of open ocean where the seals swam and where multinational schooners sealed with firearms, profiting from an avaricious market binding northern waters to furriers as far afield as Great Britain, Japan, and Russia. In the 1880s, persuaded that its land-based industry was threatened by pelagic sealers, the US tried to extend its sovereignty to open ocean, seizing foreign schooners.3 British sealers accused the US of wanting to “close up the Behring Sea.”4 To address an increasingly fractious dispute, an international arbitration tribunal was convened in Paris in 1893. The tribunal became the unlikely site of knowledge-making, generating extensive documentary practices to track seal migration, from animal censuses to seizure maps.

“What is a migratory animal, pray?” US counsel Edward Phelps asked. “It is an animal that goes away and comes back again, is it not?”5 For the US government, the ocean, as conceived in Western, non-Indigenous international law, was a “fabric that was full of holes.”6 In this tradition, states claimed jurisdiction of so-called “territorial waters,” three nautical miles from their shores. Beyond this distance, no one state had any more claim to the water—or fur seals swimming in it—than any other. These “free” waters, an equivocal term, suggested uncultivated ocean open to imperial claim. As such, the tribunal’s thousands of pages left unexamined longstanding Unangan, Alutiiq, and Makah relationships, among others, to the region and its wildlife.7 For the US, if the Bering Sea bore little resemblance to the property regimes at the core of settler-colonial expansion on land, then the arc of the seal’s migration—back and forth between land and water—was a means of extending US empire across ocean. To make this case required firmly anchoring swimming, undulating fur seals to the Pribilofs’ particular landscape.

-

The Pribilof Island group includes St. George, St. Paul, Otter, and Walrus Islands. ↩

-

The US government leased rights to seal hunting first to the Alaska Commercial Company and later to the North American Commercial Company. ↩

-

See Rebecca MacLennan, “The Wild Life of Law: Domesticating Nature in the Bering Sea, c. 1893,” in Looking for Law in All the Wrong Places: Justice Beyond and Between, eds. Marianne Constable, Leti Volpp, and Bryan Wagner (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), 15–36. ↩

-

“Oral Argument of Hon. Edward J. Phelps,” in Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings of the Tribunal of Arbitration Convened at Paris, vol. 15 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1895), 6. ↩

-

Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings, vol. 15, 48. ↩

-

Lauren Benton, A Search for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 2. ↩

-

The tribunal didn’t question the rationale for continued commercial killing; the British and American counsels were adamant that seals were not food and ignored, if not outright obstructed the subsistence hunting long practiced by Indigenous communities. Commercial fur quotas superseded all else; in 1880s, the Alaska Commercial Company would write to the Department of Treasury requesting “to furnish to natives of Seal Islands quantity of corned beef and condensed milk to be used for food in lieu of pup seal meat and ask that the seals to be killed for food shall be restricted to such number as may be necessary after the supplies in question shall have been furnished free of charges.” W. Window to H. Woulton telegraph received at Port Townsend 1881, Pribilof Islands Collection, APRCA, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. ↩

Fur seals, of course, observed no national boundaries in their thousands of seasonal miles. And until the tribunal, no wild animal had ever been the subject of an international dispute. But US counsel argued that the animals’ migratory behavior opened them to ownership. Though seals were wild by nature, US counsel claimed, lodged deep within was an animus revertendi, a will to return. This animus, described in English and American common law, offered an exception to the established idea that wild animals belonged to no one. Although not specifically addressed in common law, the seal resembled those that were so named: as honeybee and carrier pigeon returned to hive and dovecot, US counsel suggested, the seal returned to its rookery.1

To make fur-seal migration legible to Western law, both US and British counsels employed expert witnesses. In their arguments, US counsel was uniquely attached to establishing the seals’ “true home,” seeking explanations that exceeded conventional migratory theories of dead reckoning or evolutionary adaptation. Instead, they argued, a superlative “love of the nesting ground” propelled the seals.2 “Home,” in this case, was expropriated land. The seals’ apparent domestic nature naturalized the settler-colonial state’s claim to the Pribilofs as domestic territory. Defending its call to outlaw pelagic sealing as a protection against seal “extermination,” US conservationism was inseparable from preserving the paternalist nature of island governance and inequitable treatment of Unangan sealers and their families.3

That the seals returned to topographically measurable, stable ground was held up as significant; their life in the water was accepted as something of a mystery. But into arguments on both sides crept the uncertain expanse of the more than seven hundred thousand square miles of ocean where the seals swam. To the extent that those involved in the tribunal imagined where the seals went and how they travelled, it was clear they could not rely on the bluntness of legal tools to make up for the expansiveness of the North Pacific and its marginal seas. These waters saw less commercial traffic and fewer infrastructural projects, such as telegraph lines, than the Atlantic, even if trade and a market for its marine life had long made the waters global.4 An 1871 US Hydrographic Office “List of Reported Dangers in the North Pacific” compiled unconfirmed reports of “discolored” seas that “swarmed with seals and sea elephants” at latitudes far south of the Pribilof Islands.5

-

The whale, by contrast, “belongs in the sea always,” Phelps said. “Oral Argument of Hon. Edward J. Phelps,” Proceedings, 119. See Bruce W. Frier, “Bees and Lawyers,” The Classical Journal 78, no. 2 (1982–83): 105–114; E. J. Cohn, “Bees and the Law,” Law Quarterly Review 218 (1939): 289–294; and John H. Ingham, The Law of Animals: A Treatise on Property in Animals Wild and Domestic and the Rights and Responsibilities Arising Therefrom (Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson & Co., 1900): 16–20. ↩

-

Wells Woodbridge Cooke, Report on Bird Migration in the Mississippi Valley in the Years 1884 and 1885, ed. C. Hart Merriam (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1888), 11. ↩

-

Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings, vol. 15, 42. ↩

-

The Bering Strait has been the subject of important recent scholarship, see: Bathsheba Demuth, Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait (New York: W.W. Norton, 2019) and Jen Rose Smith, “‘Exceeding Beringia’: Upending Universal Human Events and Wayward Transits in Arctic Spaces” EDP: Society and Space (2020): 1–18. ↩

-

Reported Dangers to Navigation in the Pacific Ocean, Inclusive of the China and Japan Seas and the East India Archipelago: Compiled Systematically Arranged, and Collated in the United States Hydrographic Office Washington, DC (US Government Printing Office, 1871), 8. ↩

To construct the seal’s life in the water, lawyers turned to those whose livelihoods were sustained by them. Indigenous and foreign sealers, furriers, mariners, oil merchants, chiefs, and priests gave depositions on seal sightings. Could they tell the fur seals’ destination from the direction they travelled? Could they identify where old bulls spent the winter? More pointedly, did they know of other landscapes on which seals “hauled out”? The US wanted to claim seals were “appurtenant” to the islands (a specific term of real property more often used for subsurface mineral rights), making seal liveliness a right attached to ownership of the Pribilof Islands.1 Such an understanding would not stand if the seals made landfall elsewhere.

Ivan Krukoff, a 46-year-old Unangan sealer who had lived in the village of Makushin all his life and used a baidarka to hunt, testified that he had never “heard any old men say they ever saw any old seals haul out.”2 Samuel Kahoorof, a hunter of sea otter and blue fox on Attu Island, reported seeing only three fur seals in the region in the last twenty years, travelling parallel to the shore in May 1890.3 George Ketwooschish, a fisherman whose herring-oil business took him to all the “islands and rocks” of Chatham Sound, stated that no one who purchased his oil had heard of seals.4

Although the depositions answered to carefully circumscribed questions, they frequently suggest extra-legal, embodied knowledge of seal locomotion, including sealers’ inherited vocabularies for finning and rolling and their theories on how sleeping seals buoyed themselves in the water. Many of the Indigenous sealers, for instance, noted that seals became wild only after commercial killing by firearms began—incited to wildness by “the indiscriminate shooting of them in the water.”5

-

“We are here on our own territory, dealing with a race of animals that is appurtenant to it; begotten there, born there, reared there, living there seven months in the year, protected from extermination that has overtaken their species in every other spot on the globe …” Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings, vol. 15, 42. ↩

-

Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings, vol. 3, 208–209. ↩

-

Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings, vol. 3, 214. ↩

-

Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings, vol. 3, 251. ↩

-

Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings, vol. 3, 369. ↩

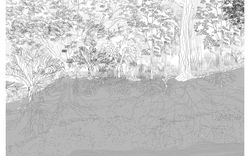

Nonetheless, a definitive migration chart was made from the depositions. One of the more visually striking documents the tribunal produced, it is also a telling representation of what the lawyers and arbitrators had in mind as they debated migration. Cropped to the eastern corner of the North Pacific, the migratory path is a dense gyre of red and black dots—representing female and juvenile seals—moving like a riptide up the California coast, past the Gulf of Alaska, bottlenecking between Unalaska and Unimak Islands, before sweeping toward St. George and St. Paul. Labels fixed along the path indicate the dates seals passed by. Made under the auspices of US Coast and Geodetic Survey superintendent Thomas Corwin Mendenhall, an autodidact not of animals but of meteorology, the chart depicts only the return journey. The seals simply materialize near San Francisco in January, moving in preternatural synchrony.1 At once elemental and oriented, the way a car traverses a road or a ship a sea lane, this imagining of animal migration is bound by human concerns and depicted as traffic from point A to point B. Mapped relative to the hard land borders of nations, the ocean is left blank.

-

The British counsel objected to the chart’s lack of information on the seals’ whereabouts for half the year. The US counsel’s own expert ornithologist, C. Hart Merriam, described migratory movement not as a single movement but “a series of successive movements or waves,” often with “stragglers.” A corrected chart would later be submitted. ↩

Seizure maps, adopted from maritime law constituted a further technique employed to triangulate the animals’ movements across open ocean. To enforce US sovereignty, Treasury Department Revenue Cutters tracked foreign schooners as they hunted seals, seizing those perceived to be in US waters. Maps made from captured schooners’ logbooks reconstructed their journeys to provide legal evidence of their trespass. Points indicated locations, dates, and tallies of seals caught; triangulated, they revealed where seals congregated in deep ocean. Comparing maps, the tribunal identified “areas of abundance” and “zone[s] of thick seal-life.”1

-

“Oral Argument of Sir Richard Webster, QCMP on June 14, 1893,” in Fur Seal Arbitration: Proceedings, vol. 14, 103. ↩

By plotting the sea like a landscape, both British and US counsels tried to establish the effects of pelagic sealing. Overlain with neatly inked bodies, seizure maps had the appearance of studies of crowd behavior. Their conclusiveness, though, like the tribunal’s other documentary practices, would prove elusive. Because seals were only recorded when schooners were present, it was difficult to know whether seal crowds or their absence represented natural fluctuations, animal behavior, or human-caused decline brought on by criminal activity, i.e., the catching of nursing mothers.

What was clear was that fur seals came ashore each year to the same rookeries, which extended inland by as much as five hundred feet. These rookeries were identifiable even when the seals were absent. The edges of their projecting basaltic rocks had been polished by bodies and flippers and the ground itself was unusually smooth, a combination of felted fur and vegetation ground down by the churn of bodies in motion. When the seals were in residence on St. Paul in 1886, as Captain Charles Abbey of the Revenue steamer Corwin described it, the air was full of “pucker and fuss” and “bellowing all the while.” “All along the rocks,” thousands of seals resembled “at a mile or so off, a lot of mammoth leeches … jumping and squirming & fighting, and the noise would remind you of the vicinity of immense stockyards.” To count seals was a task likened by a US Navy lieutenant as “almost on a par with that of numbering the stars.”1

-

Captain Charles Abbey letter to his wife from St. Paul, June 29, APRCA, University of Alaska, Fairbanks. Washburn Maynard, “Report to the Secretary of the Navy,” in Alaska Seal Fishery Lease: Letter from the Secretary of the Treasury, 7 February 1871, 5. ↩

This was the dawn of federally-funded censuses of wild animals, instigated by declining fish stocks and the 1871 establishment of the US Commission of Fish and Fisheries. At the fur-seal tribunal, numbers were not so much authoritative science as political arguments. After purchasing the islands from Russia, US agents had sought out historical enumerations of the seals, asking Russian Orthodox priests and Unangan residents for their numbers and memories accounting for the years between 1786 and 1867. But one of the US government’s own enduring counting techniques was devised by Henry Wood Elliott, who came to the Pribilofs in the 1870s as a Treasury Department agent and self-taught landscape artist.1 With an eye for delineating land acclivities, slopes, and hidden depths, his approach to counting seals was topographic. He mapped the seals’ positions—reclining, resting—and calculated the area each occupied. Then, standing on a bluff above the Nah-speel rookery to view the press of animal bodies below, he drew a one-hundred-square-foot area, finding it enclosed the tessellated bodies of eighteen breeding females, four virgin females, twenty-four new pups, and “one old bull, or ‘sea catch’”.2 Convinced that the seal, “prompted by a fine consciousness of necessity to its own well-being,” would obey this “law” of distribution at each rookery, he proposed his drawing as the standard “unit of computation” for calculating the yearly population of breeding seals.3

-

In 1871, Elliott produced topographical and bathymetric charts as part of the survey party for Yellowstone National Park. For the rest of his life, he campaigned for fur-seal conservation and was involved in the 1911 North Pacific Fur Seal Convention that outlawed pelagic sealing. ↩

-

According to Elliott, he made the diagram in July 1872 or 1874. His estimation was used by the government for almost two decades, according to Kurkpatrick Dorsey, _The Dawn of Conservation Diplomacy: U.S.–Canadian Wildlife Protection Treaties in the Progressive Era: (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2010). ↩

-

Henry Wood Elliott, A Monograph of the Seal-Islands of Alaska (Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1882), 49. ↩

Elliott’s calculations would prove to be an overestimation. But his devising of a counting technique reveals the prominent role given to numbers within an emerging idea of conservation uninterested in the seal’s place in vast ocean ecosystems. Recently, prompted in part by increasingly sophisticated animal tracking technology and its revelations of a world of movement far more extraordinary than imagined, researchers have asked how historical ideas of migration could have missed so much. The science journalist Sonia Shah, for one, finds a history of privileging rooted existence as the default position of planetary life. Such an assumption, she suggests, inherited from Enlightenment natural sciences, has both limited questions asked of human and nonhuman migrations, and frequently, pathologized their transit.1 The documentary practices—logbooks, maps, censuses—by which ideas of migration have been recorded further winnowed and particularized these perspectives. Censuses like Elliott’s quantified seals, using the language of capitalism; seizure maps carried property law out to sea; each authorized indirect reports of migration for imperial, economic, and legal interests. Above all, the settler-colonial project of making seals a “domestic” resource meant their migration was approached with tools designed to manifest a world ordered by possession, boundaries, and hard lines. It excluded information that didn’t fit—often local and Indigenous knowledge—in ways that continue to constrain human-animal relations and the analysis of their role in issues like biodiversity loss.

-

Sonia Shah, The Next Great Migration: The Beauty and Terror of Life on the Move (London: Bloomsbury, 2020). In the context of US colonialism in the Bering Strait and Alaska, see Jodi Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011); Smith, “‘Exceeding Beringia’”; and Juliana Hu Pegues, Space-Time Colonialism: Alaska’s Indigenous and Asian Entanglements (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2021). ↩