Misperforming Road Ecologies

Laura Pappalardo traces multispecies and labourer perspectives in the making of the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes

Nhe’ery sings.1 An assemblage of rhythms, sounds, and tones form Nhe’ery—the wind, the singing of birds, the steps of insects upon leaves. Nhe’ery sustains all forest beings—including its trees, sounds, shadows, fog, rivers, rocks, air, ground, underground lives, and spirits—in reciprocity. As Guarani Mbya spiritual leader and filmmaker Carlos Papá says, knowing how to walk in Nhe’ery demands a harmony with each surrounding element: the wind, the path of ants, the trail of boars.2 Nhe’ery is also Ka’aguy.3 According to Papá, Ka’aguy Rupa means the existence of an atmosphere upon and below the trees that flows as an energy through the forest and the forest floor. Nhe’ery is the space where Nhanderu created everything the Guarani need for nourishment and living, with no dependence on external supply. With its fog and humidity, fabricated by twenty thousand different plant species and made up of trees up to fifty metres high and roots up to eighteen metres deep, Nhe’ery is where the spirits bathe.4

-

According to the filmmaker and Guarani Mbya spiritual leader Carlos Papá, in Guarani Mbya, nhe’e means to sing. It also means spirits, words, and sounds of birds. I learned about the meaning and complexity of Nhe’ery in a talk with Carlos Papá, during the symposium Alteridades Vegetais: Emaranhamentos multiespecíficos com as plantas. The event brought together Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers, thinkers, and scholars to discuss “plant interactions,” alliances with non-human beings, and alternative interdisciplinary responses to the current environmental and climate crisis. Carlos Papá, “Cuidados e cultivos” (Alteridades Vegetais: Emaranhamentos multiespecíficos com as plantas, FFLCH-USP, São Paulo, 29 November, 2022), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gj-R3DDoMdQ. See also: Carlos Papá, “Nhe’ery,” SELVAGEM ciclo de estudos sobre a vida, 27 November 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uGhezj9TOog and https://selvagemciclo.com.br/en/nheery-guarani/. ↩

-

Papá, “Cuidados e cultivos.” ↩

-

According to Papá, Ka’a means forest, or herbs, and guy means shadow below the trees. Papá, “Cuidados e cultivos.” ↩

-

Papá, “Cuidados e cultivos.” ↩

Nhe’ery Infrastructures

A thick, interwoven network of infrastructures hold the singing of Nhe’ery. As Guarani Mbya leader Timóteo Verá Tupã Popygua elaborates in his book A Terra é uma só, Nhamandu created the xiguyre (armadillos) as one of the first inhabitants of yvy (Earth).1 The xiguyre excavated the first hole in yvy to raise their cubs.2 Armadillos are savvy ground engineers. With their long and sharp frontal claws, they can build a five-metre-deep underground tunnel in about twenty minutes. At night, when the xiguyre leave their tunnels to find food, another seventy species co-inhabit the tunnels, where they can rest without the risk of being chased. Xiguyre tunnels repeat all over Nhe’ery‘s original 1 300 000 km2, as underground networks of multispecies care.

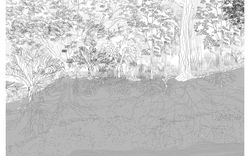

Interwoven with xiguyre‘s tunnels are those of leafcutter ants. Experts in building chambers for growing fungus, their main food source, leafcutter ants maintain complex underground networks for mobility and food supply. Their tunnels collaborate with the growth of plants, making the soil more penetrable by roots. Leafcutter ants find most of their food in the litterfall, a ten-centimetre-thick layer on Nhe’ery‘s topsoil. The litterfall assembles a deep ecosystem, with microbial lives, leaves, branches, and barks, decomposing and fabricating humus. More than one million beings inhabit one square metre of ten-centimetre-deep litterfall. Xiguyre and leafcutter ant tunnels are two among thousands of Nhe’ery‘s ground-underground infrastructural webs.

In the 1500s, colonizers renamed Nhe’ery to Mata Atlântica or “Atlantic Forest,” a biome in “Brazil.”1 Translating Nhe’ery (the space where spirits bathe, where the xiguyre build their tunnels, and which sustains the Guarani way of life) to Atlantic Forest (a source of resources for juruá2 colonial extraction) was one method through which colonialism promoted the dispossession of the Guarani Mbya and other-than-human lives from their territories.

In October 1976, surrounding Jaraguá Peak, earth scrapers muted Nhe’ery. From 1976–1978, machines demolished xiguyre and leafcutter ant tunnels to build Rodovia dos Bandeirantes.

What does it mean to humanize a road?

“O Governador do Estado de São Paulo, a Secretaria dos Transportes e a DERSA-Desenvolvimento Rodoviário S.A. sentem-se orgulhosos em entregar ao povo brasileiro a Rodovia dos Bandeirantes. A estrada, parte do sistema rodoviário integrado Anhanguera/Bandeirantes, foi construída segundo a mais avançada tecnologia, para oferecer a máxima segurança aos seus usuários. Humanizar estradas é isso.“

“The Governor of the State of São Paulo, the Department of Transportation, and DERSA-Desenvolvimento Rodoviário S.A. are proud to deliver the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes to the Brazilian people. The road was built according to the most advanced technology, to offer maximum safety to its users. This is what it means to humanize a road.“1

-

DERSA, “Rodovia dos Bandeirantes II Seminário DERSA” (seminar, São Paulo, November 1978). ↩

Inaugurated on 28 October 1978, the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes opened for traffic in the middle of the Brazilian military dictatorship, with two roadways, six lanes for traffic, and a capacity for seventy thousand vehicles per day. Precisely nine hours after construction concluded, then-Brazilian president Ernesto Geisel and his successor João Batista Figueiredo travelled for three hours along the 88.46 kilometre road, symbolically activating it for public use.1 DERSA (Desenvolvimento Rodoviário S/A), the public company responsible for the road construction, distributed 2,200 invitations for the inauguration. The event culminated at the Obelisco Diamante dos Bandeirantes—a forty-metre-high concrete tower—where, accompanied by the São Paulo orchestra, Geisel untied the ribbon to officially open the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes for car traffic.2

-

“1978: Rodovia dos Bandeirantes é inaugurada para ligar São Paulo a Campinas e desafogar Anhanguera,” Folha de S.Paulo, 28 August 2017, https://acervofolha.blogfolha.uol.com.br/2018/10/28/1978-rodovia-dos-bandeirantes-e-inaugurada-para-ligar-sao-paulo-a-campinas-e-desafogar-anhanguera/. ↩

-

DERSA was created in 1969 to expand the road infrastructure network in the state of São Paulo. ↩

The road’s namesake, the Bandeirantes, were sixteenth and seventeenth century settlers who organized expeditions to expand the Portuguese empire. Departing from São Paulo de Piratininga, as the region that would become the city of São Paulo was known in the 1550s, the Bandeirantes walked through Indigenous trails to chase and enslave Indigenous peoples for the production of sugar, transport of agricultural products, and building of Portuguese villages.1 The Bandeirantes enslaved and displaced Guarani, Tupiniquim, Guaianá, Tabajara, Tamoio, Temiminó, Guarulhos, and Caiapó do Sul communities, families, nations, who had been living and traveling for centuries through these lands. The name Rodovia dos Bandeirantes remains vastly criticized by Guarani activists and leaders who denounce the colonial violence that the road maintains. Rodovia dos Bandeirantes pays homage to genocidal colonizers.

Since the 1500s, mobility infrastructures have concretized settler-colonial expansion in Brazil. As the slogan for the São Paulo mayor, governor, and Brazilian president Washington Luís’ 1920 electoral campaign for governor declared: “to govern is to open roads.”2 Rodovia dos Bandeirantes, as part of a larger network of state and federal roads, fragmented yvyrupa.3 The Guarani concept of yvyrupa determines the amplitude of the Guarani Mbya traditional territory. For the Guarani, yvyrupa means a world without frontiers, and the refusal of frontiers imposed by nation-states.4 It was also the name of the Guarani territory before the arrival of settlers. On this terrestrial platform, Guarani kinship is structured by spatial mobility as a fluid migration—through continuous networks and exchange of news, seeds, rituals, and plants for traditional medicines.5 Entangled as human and other-than-human mobility infrastructures—such as Indigenous trails connecting Guarani villages, which opened small paths in reciprocity with forest infrastructures—these mobility networks coexisted without deforesting surrounding Nhe’ery. As the Guarani Mbya Xeramoï Nelson Florentino says:

-

São Paulo exists entirely within Guarani territory. Two Guarani Mbya Indigenous Lands overlap with the urban area of the city of São Paulo: the Jaraguá Indigenous land in the northwestern portion of the city, and the Tenondé Porã Indigenous Land in the south of São Paulo. As of 2021, eighteen Guarani villages exist in the city of São Paulo (six of them in Jaraguá Peak), in addition to sixteen archaeological sites. Within the larger area of the state of São Paulo, about eighty-five Guarani villages existed in 2021, and around 210 archaeological sites. According to a report from 2012, 37% of Indigenous populations (324,834 people) in Brazil live in urban areas. See: Povos Indigenas no Brasil, “Quantos São?,” https://pib.socioambiental.org/pt/Quantos_s%C3%A3o%3F. ↩

-

During Washington Luís’ mandate as governor, he built 1,326 kilometres of new roads in the state of São Paulo. See: “Governar é abrir estradas: Washington Luís, o terceiro prefeito de São Paulo,” São Paulo in foco, 2014, https://www.saopauloinfoco.com.br/terceiro-prefeito-washington-luis/. ↩

-

Yvyrupa can translate to “terrestrial support,” or “terrestrial platform”: yvy means terra (earth), and rupa means support, platform, or place of permanence. Yvyrupa can also translate to “embodied earth” or “earth as body.” See: Daniel Calazans Pierri, “A caminho do sol,” in Nas Redes Guarani: saberes, traduções e transformações, eds. Dominique Tilkin Gallois and Valéria Macedo (São Paulo: Hedra, 2018), 35. ↩

-

Maria Inês Ladeira, “Comunicação, convívio e permuta em Yvy vai,” in Nas Redes Guarani: saberes, traduções e transformações, eds. Dominique Tilkin Gallois and Valéria Macedo (São Paulo: Hedra, 2018), 266. ↩

-

Spensy Pimentel, “Relatório Circunstanciado de Identificação e Delimitação da Terra Indígena Jaraguá” (Brasília, Funai/Ministério da Justiça, 2009), 55. ↩

“The Guarani didn’t walk along the road, they walked according to the constellation of the stars. This is the path that the ancient Guarani followed. They didn’t follow the asphalt. We, the ancient Guarani, followed the constellation to reach the land without evil, to reach Nhanderu. Nhanderu would tell us which path to follow. Today, we don’t do this anymore.”1

-

Interview with Nelson Florentino, Xeramoï Guarani, by Chão Coletivo in August 2022. Chão Coletivo is a research group, composed of Guarani and non-Indigenous researchers, structured on the alliance between Guarani residents and leaders of the Tekoa Pyau and a group of non-Indigenous collaborators linked to the research platform “Nas Ruas: territorialidades, memórias e experiências” at the School of Architecture and Urbanism Escola da Cidade. The group seeks an encounter between techniques and knowledge of the forest and the city, investigating possible tools for another way of inhabiting the metropolis of São Paulo. ↩

If, for the Guarani, the terrestrial platform is one unbounded, roads are as harmful as nation-state borders. Car-centred roads—like Rodovia dos Bandeirantes—crumble yvyrupa.

The first step in the construction of the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes was to negotiate the expropriation of 1,463 properties and open up fourteen million square metres to build the road.1 The second step, as one DERSA engineer declared, was to remove more than two hundred “interferences”: “oil and gas pipelines, water mains, electricity, telephone transmission, and railway lines.”2 Eerily, the Atlantic Forest was not mentioned in the list of interferences to be removed from the road’s path, erasing the deforestation process from the report. Rodovia dos Bandeirantes’ construction was also the removal of 51.5 million cubic meters of earth and forest.3 In some cases, the report strategically identified Atlantic Forest as “swamp areas,” which justified the forest removal. Technical architectural and engineering drawings depict the Atlantic Forest as empty, erasing xiguyre tunnels and the Guarani Mbya families that inhabited Jaraguá Peak forest, and facilitating the invisible and uncounted expropriation of Indigenous and other-than-human inhabitants.4

-

DERSA, “Rodovia dos Bandeirantes II Seminário DERSA” (seminar, São Paulo, November 1978). ↩

-

DERSA, “Rodovia dos Bandeirantes II Seminário DERSA.” ↩

-

In the first stretch alone, where Jaraguá Peak is situated, DERSA estimated to extract 400,523m3 of soil per month. ↩

-

Jaraguá Peak is an important spatial reference for the Guarani as a resting point in between Guarani villages since before Portuguese colonization. In the 1500s, gold miners and Bandeirantes displaced and enslaved Guarani inhabitants in Jaraguá Peak. Since the 1950s, Guarani families have reclaimed their territories in Jaraguá Peak, stewarding one of the last spots where Nhe’ery remains within the city of São Paulo. During the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes construction, the São Paulo state government did not demarcate the forest in Jaraguá Peak as an Indigenous land. At that time, the 1988 constitution, which established the demarcation of Indigenous lands, did not yet exist. Guarani territory in the Jaraguá was first acknowledged in 1987, by the Decree n. 94.221. However it only recognized the footprint of Guarani houses as the Indigenous territory, not including the land that they relied on for living. This lack of recognition caused serious problems for the Guarani living in the Jaraguá. ↩

Rodovia dos Bandeirantes performed the role of territorial financialization. A report by DERSA stated that Rodovia dos Bandeirantes’ main goal was to create new development poles along the road margins.1 One part of the construction, nearly 21 000 metres in length, was planned to cross in the middle of Guarani villages surrounding Jaraguá Peak, dividing houses into different sides. Meanwhile, São Paulo’s government created a zoning law to regulate the road area, opening space for commercial zones, service zones, and areas destined for logistics.

In the years following the road’s inauguration, the noise of cars and trucks, bus lines, warehouses, and real estate high-rises replaced Guarani houses, forest, and areas for fishing and hunting. Real estate companies sold areas long used by the Guarani to private buyers, transforming ancestral Nhe’ery into pieces of land for sale.2 Thiago Guarani Karai Djekupe, architect and Guarani Mbya leader from the Tekoa Yvy Porã in the Jaraguá Indigenous Land, describes how, before the road construction, his family walked freely:

“Antes de ter essa rodovia, o meu avô, meus tios e meus pais sempre andaram muito livres aqui. Antes dos meus avós chegarem aqui pra ficar no Tekoa Ytu, o André Samuel morava do lado de lá da Bandeirantes, não existia a Bandeirantes, era um lado que tinha nascentes, tinha caça, tinha animais, e aí o juruá foi e passou a rodovia. Quando fez essa rodovia, não havia nenhum tipo de estudo de impacto, de impacto com a comunidade, de impacto ambiental. No correr do tempo, a gente veio vendo tanto pela homenagem que é feita, Rodovia dos Bandeirantes, quanto também pela quantidade de atropelamentos que a gente teve. Com muito barulho, pessoas que invadiam a comunidade através desse lado da rodovia, então conseguia ter acesso à aldeia, também os caminhões quando passam e estouram os pneus, as casas tremem por causa disso. O barulho é contínuo, principalmente à noite, quando a gente tem que ter um pouco mais de silêncio, o barulho da via fica muito mais alto. Isso traz, de certa forma, um certo incômodo, atrapalha na reza, no nosso culto, nas nossas cerimônias. A gente percebe que por essa questão da vida do juruá estar cada vez mais invadindo o nosso território.“

“Before this highway, my grandfather, my uncles, and my parents always walked freely here. Before my grandparents arrived here to stay in Tekoa Ytu, André Samuel lived on the other side of the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes. That side had springs, hunting, animals, then the juruá built the highway. There wasn’t any kind of impact study, of impact with the community, of environmental impact. As time went by, we could see the road’s impact, both because of the tribute paid to the Bandeirantes, and because of the number of people that were run over by cars. The road brought a lot of noise, people invading the community through this side of the highway, and also the trucks, when they pass by and blow out their tires, which made the houses shake. The road noise is continuous, especially at night, when we have to be a little quieter, the noise from the road is much louder. This brings discomfort; it hinders our prayers, our ceremonies. The juruá is invading our territory more and more.”1

-

Interview with Thiago Guarani Karai Djekupe conducted by Chão coletivo in May 2022, for the project: “Memórias, saberes e técnicas construtivas dos Guarani Mbya na Terra Indígena do Jaraguá” (Memories, knowledge and construction techniques of the Guarani Mbya in the Indigenous Land of Jaraguá), of which Djekupe also participates. ↩

Built on a razed portion of the Atlantic Forest, the road interrupted Guarani and other-than-human mobility flows, such as those of boars, ants, bees, and armadillos, to open space for automotive, human, and juruá (non-Indigenous) mobility. Ten-centimetre-thick Nhe’ery‘s litterfall, with more than one million inhabitants, was sterilized by a ten-centimetre-thick monoculture of asphalt. Despite the road’s claim of being the most modern and safest infrastructure, it is only safe and humanized for a select portion of the population.

Guarani Mbya Urban Forest Infrastructures in São Paulo

The Guarani communities in the Jaraguá Indigenous Land have long organized against the colonial violence of road-making.1 At the beginning of the 1980s, groups organized by Guarani leaders, spiritual leaders, and xondaros and xondarias (youth Guarani who are on the front line of political actions and resistance) articulated movements pressuring the government to demarcate Indigenous Lands.2 Protests in 2013 and 2019 obstructed access to the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes, using the same infrastructural networks that divide their territory as tactics of resistance. According to Thiago Guarani Karai Djekupe:

-

Guarani activist groups from the south and southeast of Brazil have an Indigenous collective organization called Guarani Yvyrupa commission (CGY), which advocates for the recognition of the Guarani territorial rights. ↩

-

Lucas Keese dos Santos, A esquiva do xondaro: movimento e ação política entre os Guarani Mbya (Editora Elefante, 2021), 255. ↩

“Nós somos guardiões da terra, não donos dela. Estamos para proteger, porque nós fazemos parte da terra. E quando a gente ocupou a Bandeirantes foi nesse sentido de dizer que nós estávamos, de certa forma, um dia atrapalhando a vida do juruá ali naquela passagem, mas quantos foram os dias que eles atrapalharam a nossa vida também e atrapalham até hoje com as suas ameaças? […] E foi para trazer uma reflexão, para trazer um incômodo, mas o que aconteceu foi que grande parte da mídia que estava discriminando, marginalizar ainda mais, que não tínhamos o direito de atrapalhar o ir e vir das pessoas, mas o nosso ir e vir não é garantido nessa estrutura de Estado, não é garantido. Então todos, tanto a Anhanguera, que passa ali, o Rodoanel que passa aqui e a Bandeirantes que passa aqui, elas cercam o nosso território, nos mantêm presos numa situação que a gente tem que encontrar outras soluções, nós como um todo: a nossa vida de Guarani, a nossa vida dos pássaros, a nossa vida dos animais e todos que vivem aqui. As próprias árvores quando precisam que suas sementes sejam semeadas, espalhadas, tem um limite também porque a via impede isso. E aí a gente tem esse impedimento. Ocupar essa via foi para tentar trazer uma reflexão que talvez seja muito lenta ainda para o juruá conseguir abraçar essa discussão. Mas foi um ato de resistência do nosso povo.“

“We are guardians of the land, not landowners. We protect the land because we are part of it. When we occupied the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes in 2013, it was with this intention. We were, in a way, disturbing the life of juruá for one day, but for how many days have they disturbed our life? […] We closed the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes to bring a reflection. But the media criminalized us even more, saying that we had no right to interfere with people’s coming and going. But what about our coming and going? It is not guaranteed by the state in this structure. The Anhanguera road, the Rodoanel road, and the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes surround our territory, keeping us trapped in a situation in which we have to find other solutions, us as a whole, our Guarani life, our bird life, our animal life, the life of all that are here. The trees themselves, when they need their seeds to be sown and spread, they have a limit because the road prevents it. The occupation of the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes was an attempt to bring a reflection that may still be too slow for the Juruá to be able to embrace. But it was an act of resistance by our people.”1

-

Thiago Guarani Karai Djekupe, interviewed by Coletivo Chão, May 2022. ↩

This resistance also comes in the form of promoting multispecies roadmaking. In the Ytu and Yvy Porã Guarani villages in the Jaraguá Indigenous Land, Guarani communities have been reconstructing bee infrastructures. As of 2021, Guarani villages in the Jaraguá are raising twenty-eight beehives and seven different species of bees without sting. In return, the bees make aerial roads, pollinating areas as far as five to ten kilometres from Jaraguá Peak.1 The long-term activism and resistance of the Guarani Mbya in São Paulo, and the making of Guarani infrastructures such as networks of seed exchange between Guarani villages and practices of reforestation, are the main reason that the Atlantic Forest still exists in the city.

-

Round table discussion with Marcio Boggarim Wera Mirim and Tiago Barros, “Abelhas-sem-ferrão: biodiversidade, cultura e tradição indígena,” Sesc Itaquera, 28 April 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hg9FN1qiwmM. ↩

Maintaining Cracks

The final activity before the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes’ inauguration was its cleaning. Roads are continuously being maintained. As one of the engineers responsible for the road construction described:

“When you make a road, you make the paving. You prepare the subgrade and compact it into a base supported by the earth, followed by an intermediate layer, and the top layer. What happened in Rodovia dos Bandeirantes: builders put larger stones in the pavement, which left spaces in between the rocks, starting to accumulate water. The grass, planted on the side of the road, grew its root to get into the voids between the stones to reach the water kept in between the asphalt. All of Rodovia dos Bandeirante’s extension had grass growing on its border. The grass roots clogged the water drain outlet on the side of the road. When the water kept in between the asphalt heated up, it made the asphalt lose its adhesion to the ground. The asphalt started to crack. We had to rebuild all the road’s drainage system.”1

-

Interview with José Eduardo Junqueira Franco, July 2022. ↩

Construction problems and unpredicted system failures exist in the everyday process of roadmaking. Pruning lawns, removing debris, hand trimming, removing cutting material from the truck, covering the roadside with grass plates, cleaning and unclogging gutters, ditches, slopes, and checking conditions of inspection boxes keep the road traffic flowing. Road travellers depend on workers who keep road signs clean. Seeing a road from the perspective of the workers who build and maintain it foregrounds how roads are fragile and brittle. Reckoning the daily making and maintenance of roads also demystifies them as fixed, settled infrastructures. Instead, roads can be seen as infrastructures constantly being remade and therefore open for contestation.

Roads as Collaborative Infrastructures

How many spatial perspectives and cosmologies are left as blind spots in architecture and urban planning practices when considering only juruá standards? As DERSA’s report from Rodovia dos Bandeirantes construction has shown, creating an architectural drawing implies choosing what to depict, and what to erase. When architects, urban planners, and engineers erased the presence of the Atlantic Forest from “technical drawings”—sections, plans, and perspectives—in order to build the Rodovia dos Bandeirantes, they also designed the dispossession of Guarani and other-than-human lives, lands, and infrastructures. Architectural drawings design not only the static form of a building, but also several layers of relations: labour on the construction site, earth removal, transportation of materials, sewage and electricity connections, maintenance requirements. A line in a plan is physically situated in specific territories where complex relations between bodies, cultures, affects, and political interests keep co-existing and colliding. If architectural drawings also serve to negotiate the maintenance of lives and territorial relations with a stack of agents (public and private interests, zoning laws, and court decisions), how can architectural documents uphold the maintenance of the Atlantic Forest, Guarani land rights, and multispecies care?

The substitution, demolition, or interruption of Indigenous and other-than-human infrastructures for a juruá infrastructure that facilitates the movement of cars, trucks, and buses enables the continuation of Brazilian colonial violence in the present. Nonetheless, Guarani communities in and beyond São Paulo reclaim their territorial paths and remake Guarani geographies every day, proposing alternative infrastructural models for and beyond cities.

This essay has advocated for urban planners and architects to learn from multispecies infrastructures. Each forest inhabitant holds their own set of thick relations. The entanglements of human-bee interactions as stewarded by the Guarani communities in Jaraguá, the tunnels dug by armadillos, and the fungi chambers built by leafcutter ants are a few spatial practices that can provide clues as to how architects and urban planners can design alongside ongoing collaborative infrastructures—infrastructures of making with.1 If, as Brazilian president Washington Luís said, “to govern is to open roads,” what other governments could take place if multispecies roads were at the centre of infrastructure and urban planning practices? If roads are axes of influence on the city that will grow around it, what other cities could be built around multispecies roads? No infrastructure is built, maintained, or functions without day-to-day collaboration. Complicating the boundaries of terms such as “road” and “infrastructure” opens space for roads to exist beyond automotive monocultures, as collaborative infrastructures of care.

-

As biologist and science philosopher Donna Haraway poses: “Sympoiesis is a simple word; it means ‘making-with.’ Nothing makes itself: nothing is really auto-poietic or self-organizing.” See Donna Haraway, “Symbiogenesis, Sympoiesis and Art Science Activisms for Staying with the Trouble,” in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet (University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 25. ↩

This essay is centered on Guarani territory, in Jaraguá Peak. It honors the past, present, and future relationships between the Guarani nation and their lands. The essay was written by a juruá (of non-Indigenous, settler origin) born and raised in Guarani territory, in the region today known as São Paulo, living and learning in what is now called Brazil—a nation-state that occupied and dispossessed Guarani Mbya and hundreds of other Indigenous nations’ territories. As an architect from São Paulo, I carry many preconceptions that limit comprehending the spatial and cosmological complexities and meanings of the Guarani territory, which means this essay also faces limits in translation. Part of my unlearning as an architect is also my responsibility to respect Guarani protocols and self-determination on their lands.

First and foremost, I thank Thiago Guarani Karai Djekupe for sharing his knowledge and memories in the interview with Chão Coletivo. I thank Alexandra Pereira-Edwards for her careful work as the essay’s editor. I also thank Beatrice Perracini Padovan and Thiago Benucci for the suggestions and edits, and the Ruinorama collective for the generous debates and encounters that have taught me about seriously learning from multi-species architectures and spatial practices.